This hilltop at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park in West Virginia transformed from a barren Civil War landscape to the home of an African American institution of higher education.

Article

Camp Hill: From War-Torn Landscape to Land of Opportunity

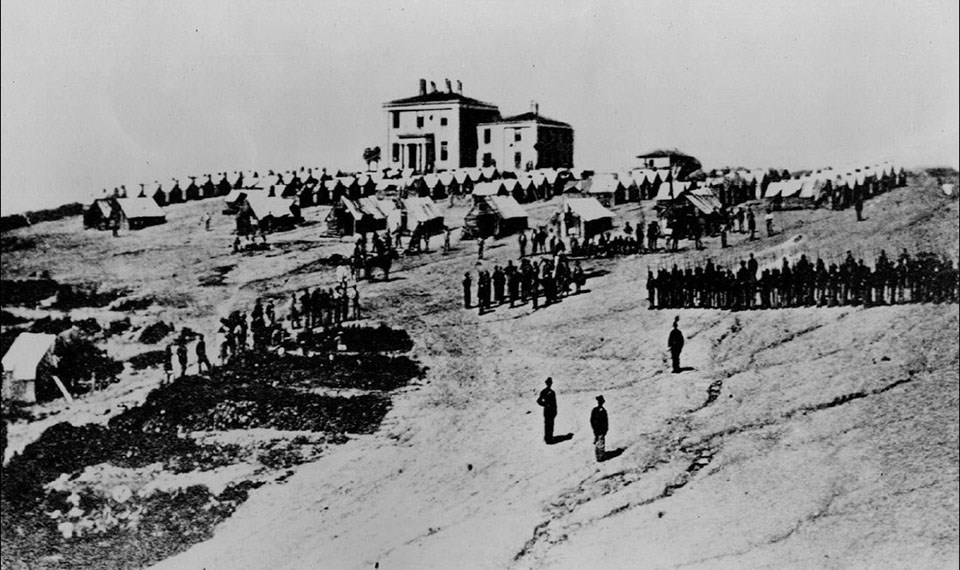

NPS, Courtesy Harpers Ferry National Historical Park Archives (in 2009 Camp Hill Cultural Landscape Report)

Camp Hill boasts a scenic view over the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers. In the 1840s, the first quarters and garden plots were built on the stony, open hilltop for U.S. Armory officials, and woodland covered the cliffs. During the Civil War, Harpers Ferry became a battleground that changed hands eight times between Confederate and Union forces, leaving the town in ruins. Soldiers camped, built earthworks, and were buried on Camp Hill, compacting the earth and stripping it of plant life.

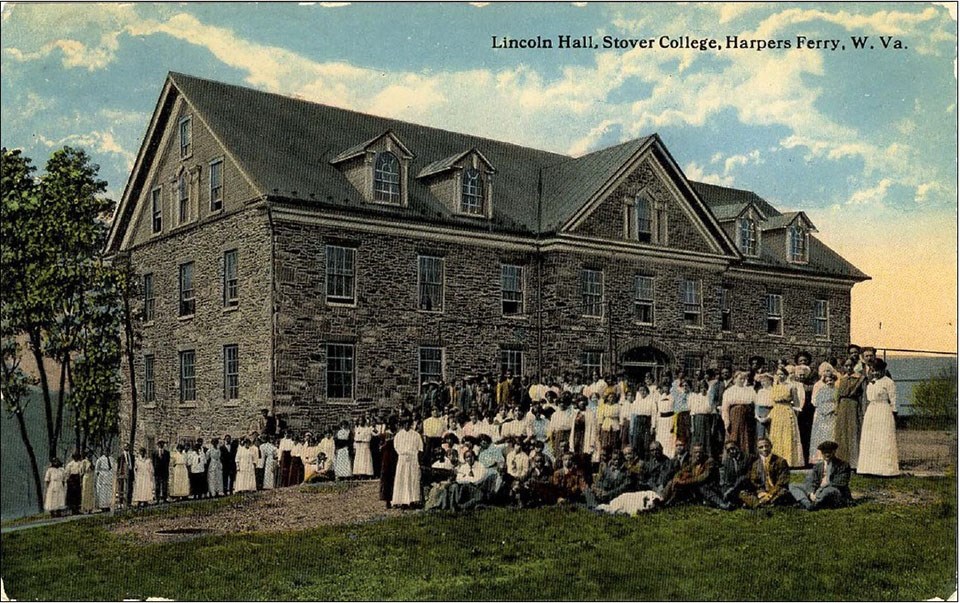

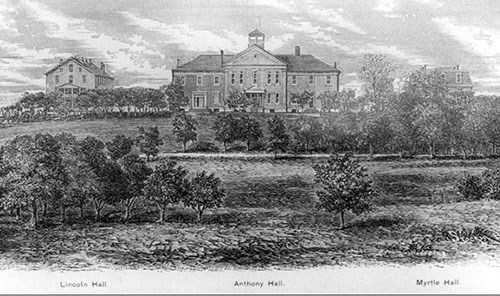

An influential African American institution rose out of the dust during Reconstruction. In 1865, Freewill Baptists started a primary school for African American freedpeople in the former Armory paymaster’s house on Camp Hill, now known as the Lockwood House. In 1867, this school grew into Storer College, a school founded to train African American teachers that was open to all regardless of race, religion, or sex.

NPS, Courtesy Harpers Ferry National Historical Park Archives (in 2009 Camp Hill Cultural Landscape Report)

NPS, Courtesy Harpers Ferry National Historical Park Archives (in Camp Hill Cultural Landscape Report)

NPS, Courtesy Heritage Landscapes (in Camp Hill Cultural Landscape Report)

Last updated: September 21, 2023