Although women married to National Park Service personnel had assisted their husbands for years as unpaid help (like the military, it came with the territory), their first appearance as "official" employees of the National Park Service occurred in 1918.

NPSHPC-HFC/YOSE#931

Early Challenges and The First ”Rangerettes”

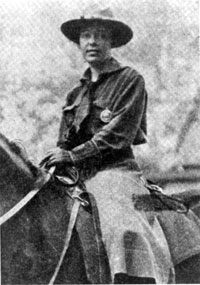

The first two "Rangerettes", as these early women were known, were Clare Marie Hodges (Wolfson) and Helene Wilson.

They were hired as temporary employees to fill vacancies left by men who responded to their country's call to arms to "save the world" in Europe. Helene Wilson, from Los Angeles, checked in vehicles in Mount Rainier National Park, while Hodges, a local grade school teacher, performed ranger service at Yosemite from May 22 to September 7, 1918.

It is not known what type of uniform, or identification, if any, that Wilson wore. There are, however, at least three photographs of Clare Hodges while on duty. From these she appears to have worn what was referred to at that time as "camping clothes". There are no pieces of regulation uniform evident, except for a badge and perhaps her hat.

In the early years, women found it very difficult to penetrate the male dominated National Park Service. Only a few foresighted people like Horace Marden Albright, then superintendent of Yellowstone, and Washington Bartlett "Dusty" Lewis, superintendent of Yosemite (who hired Hodges) gave women a chance to show that they could perform as well as a man.

Albright hired Isabel D. Bassett as a guide at Yellowstone in 1920. This started a trickle of women into the service. Marguerite Lindsley (Arnold) and Frieda B. Nelson were hired in 1925; Frances Pound (Wright), 1926; and Herma Albertson (Baggley) in 1929.

Only temporary, or seasonal, to use today's vernacular, female employees were hired to perform ranger duties. All permanent positions for women were classified as naturalists, even though some of them did occasionally perform ranger duties.

NPSHPC-YELL/130,092

Early ‘Uniforms’

Initially, the National Park Service had no provisions, uniform or otherwise, for women. Consequently, they were left to their own devices as to what they were to wear. Herma Albertson wore the standard ranger uniform, including the hat, while Frieda Nelson and Margaret Fuller wore the same uniform, but tailored for women (buttoned right to left). Others attached their badges to formal hunting coats, sweaters, or any other article of clothing that struck their fancy.

Although during these early years there was an occasional cry in the (proverbial) wilderness concerning the uniforming of women in the Service, nothing was done in the first decade of the agency’s existence.

Among recommended regulation changes submitted by the uniform committee in 1927 were two that would have affected women -- had they been implemented. One called for them to wear the regulation uniform, at the discretion of the director or park superintendent. The other though, would no doubt have created quite a furor if it had been included in the new regulations. It called for female employees not required to wear a uniform to wear a collar ornament [USNPS] "conspicuously on the front of the waist of the dress".

The majority of existing photographs showing women in Park Service uniforms from this period are from Carlsbad Caverns. These show that when hats were worn, at least at that location, they ran the gamut from chic little light colored items perched on the side of the ladies heads, to standard military overseas patterns of forest green wool.

NPSART-Gilbert B. Cohen, artist-HFC/ARM#GR-0002 1 thru 5

World War II-era

In the spring of 1940 the Fechheimer Brothers Company forwarded drawings for a distinctive uniform for Park Service women to the NPS uniform committee.

It is not known whether these were solicited or just a bit of entrepreneurship on the part of Fechheimer -- Fechheimer was a very aggressive and active company.

Unfortunately, since these drawings have not been located we have no way of knowing exactly what the uniforms looked like.

From the correspondence it can be determined that they contained two different uniforms, "A" and "B"; that one of them, apparently "B", had a short coat, while "A" 's coat was of the longer variety, similar to the men's; and both included an "overseas" cap. A shirt with a high collar and a necktie were also defined. This uniform sounds very much like that adopted in 1947.

As word leaked out about the proposed uniforms, women began writing Fechheimer Brothers inquiring as to prices and material samples prompting Uniform Committee Chairman John C. Preston to admonish Fechheimer to "advise the one making the inquiry that to date no definite decision has been reached by the uniform committee concerning the style of uniform for women employees of the National Park Service."

The whole matter of women's uniforms was a very "controversial subject", with everyone having their own ideas as to what form it should take. Some didn't like the shirt (the style worn by men) and thought that a sports blouse should be substituted instead. Others believed that the hat should be omitted, or at least changed.

However, the December 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the resulting General Conservation Order M-73-a, which reserved wool cloth for military uniforms, temporarily halted all further speculation in Park Service uniforms.

With the able bodied men again going off to war, women, especially NPS wives, were enlisted to help in the parks, particularly in offices and entrance stations. At that time, even office staff wore uniforms. While not specified in the uniform regulations, in 1943 a material-saving uniform was created for women.

As with male employees, women who had been uniformed continued to wear the man's style coat throughout the war as long as it was presentable.

A photograph of Ethel L. Melnser, stenographer at Scott's Bluff National Monument, taken in 1944, shows her wearing essentially the same uniform worn by Lila Michaelsen, Guide at Carlsbad Caverns in 1931.

NPSHPC/HFC#96-1326

Post-War Period and the First Standard Women’s Uniform

After the war, the subject was taken up again and after much debate, a standard uniform for the women of the National Park Service was finally authorized on June 2, 1947.

The National Park Service, at last, was recognizing women. Granted, their uniform was classified under the "Special" category and there was only one, instead of the three for men, but at least they were being acknowledged as part of the uniformed establishment.

When new regulations were drawn up 1956, those pertaining to women's uniforms remained the same, even to the wearing of the men's fatigue jacket (now called the standard men's field jacket).

NPSART-Gilbert B. Cohen, artist HFC/ARM#GR-0002-6, -7

The Swinging Sixties

In 1960, the National Park Service issued a written statement on the employment of women in uniformed positions, urging administrative officials to consider fully all qualified applicants for vacancies within the Service, regardless of gender.

It states that the National Park Service should "employ in its uniformed positions the best qualified men and women available." However, it goes on to say "women cannot be employed in certain jobs, such as Park Ranger or Seasonal Park Ranger...in which the employee is subject to be called to fight fires, take part in rescue operations, or do other strenuous or hazardous work..." but that "[p]articipation by women employees in lecture programs, guided tours, museum and library work, and in research programs would be entirely appropriate and very helpful in many Parks. Increased attention may also be given to children's programs in some Parks and to extension work to schools for which women interpretive employees may be even more effective than men."

Paradoxically, the 1961 uniform regulations were very liberal in defining the uniform for women. Certain items were specifically spelled out, but variations were allowed at the numerous parks.

NPSHPC - HFC#96-1332

Uniform Inequality Continues

After distribution of the 1961 uniform regulations, complaints and suggestions began to come in from the field.

One particular item dealt specifically with women, involving the location of the badge and nametag -- there were no breast pockets on the women's jacket and thus badges sat too low for a good appearance on a woman. Some women expressed strong opinions against wearing the badge, while others were just as adamant for it.

This was later resolved by is suing the women a silver arrowhead pin, the same size as the tie tack, "in lieu of a badge", though superintendents had the option of issuing them a regular badge, if they so desired.

Mary Bradford relates that when she received her pin, she was very unhappy about it. Visitors did not consider her having any authority and would by-pass her to talk to the "ranger with the badge". So, she refused to wear it and requested a badge from her supervisor. He agreed with her and issued her a regular ranger badge. Unfortunately, when she pinned it on her uniform it proved to be too heavy for the material. But, exercising that 'old ranger know-how', She stuck the pin through her jacket and fastened it to her bra strap.

Up until July 1, 1965, women rangers had been paid the same ($100.00 initial and $100.00 yearly replacement) uniform allowance that men received. That year the allowance was increased to $125.00/$125.00 for men and $125.00/$100.00 for women. This discrepancy was no doubt due to the women's uniform ensemble being less expensive than the men's, but the frequent uniform changes were not taken into account. There were a number of variables (no coat, etc.) that would reduce the allowance. After a year, the agency restored uniform allowance parity.

Public Perception

The 1962 uniform charge had done nothing for the image of women in the Service. "Early orthopedic" and "old maid dowdy" are two of the appellations applied to this uniform by personnel in the field. It was not only unattractive, but often a "source of professional frustration" to the women wearing it.

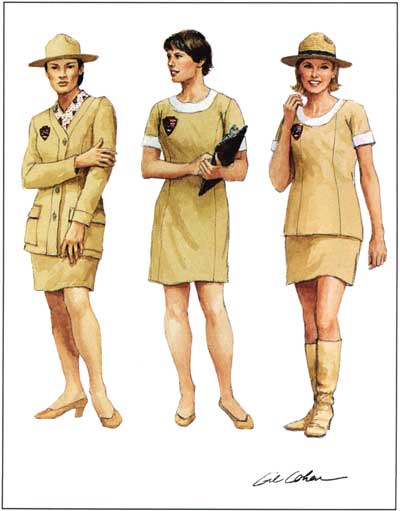

Originally designed for airline stewardesses, for whose limited activities it served well, the uniform proved totally inadequate for the varied functions and duties of the women in the Service. This was one of the main issues Director George B. Hartzog directed the 1968 Uniform Committee to address.

New uniform regulations, to become effective January 1, 1971, were drawn up and distributed to the field under Director's cover letter, dated July 2, 1969. These contain a written description, as well as crude sketches for new uniforms. The sketches appear to have been cut out of a catalogue and then outlined with pencil, or ink, in order to make them stand out, when copied.

Even though mini-skirts were in vogue, the hem of the dress and skirt were not to exceed 2 inches above the knee. It can be assumed that the uniform committee’s original idea was to have everyone in the Service dressed in the standard forest green. Even the swimsuits and terrycloth beach robe were specified to be this color.

The Female Ranger Perspective

Throughout the sixties, women expressed dissatisfaction with the uniform. The question for the agency, then, was what will satisfy the 250 permanent and innumerable seasonal women? The answer was simple: Just ask them.

Many things were brought to light by the exchanges that followed, such as:

- "The fitted jacket isn't functional or comfortable. It should move easily but look smart, particularly in the city."

- "We participate in many ceremonial functions here with the military. They always wear their dress uniforms and we look pretty drab in comparison."

- "We climb hills and mountains and rocks. It's rugged. We tried bermuda shorts with knee socks, but they didn't protect us from poison ivy, stinging nettles or brambles in meadows. We need something more functional. Loose slacks are fine and levis are great."

Another wanted a suitable uniform for escorting VIP's around town, as well as flat shoes for summer wear.

The feeling was pretty unanimous in the dislike of the present hat. All thought it was "unattractive, dated, and a threat to their hairdos."

After all the discussions, interviews and general orientation to the needs of the women in the parks were completed, the momentous task of trying to satisfy these needs, within the scope of a budgetary constraint and a minimum number of uniforms, began to emerge. Undaunted, the agency began the work of designing a new image for the women of the National Park Service.

NPSART - Gilbert B. Cohen, artist - HFC/ARM#GR-0002- 8 thru 10

1970: A New Low

The Grand Public Unveiling of the "new look" for National Park Service women took place in the Rose Garden of Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia during Freedom Week, 1970.

In all, seven different uniforms were modeled by Service wives and employees. After the formal presentation most of the people repaired to a tent set up with refreshments, while the models posed for the various photographers. There was even a film crew commissioned by Polaroid to cover the show for a special film on the National Park Service.

After the show was over, the new uniforms were packed up and Marion Riggs was selected to take the show on the road. On her way to introduce the line at the Southwest Regional Office in Santa Fe, New Mexico, she detoured to give President and "Ladybird" Johnson a private showing at their ranch near Johnson City, Texas.

Riggs states that it was one of the strangest experiences of her life. She made the trip by herself and upon arriving at the airport, discovered there was no one to meet her.

So, she rented a car and after acquiring directions, headed out to the ranch. Arriving at the gate-house, she explained that she was there to show the new Park Service uniforms to the President and was surprised when the guard didn't ask for any identification, but simply instructed her to go down this little dirt road to one of the guesthouses, probably the Cedar Cottage, where she met the "First Couple".

Using an adjoining room to change, she modeled each of the new uniforms, during which time no one spoke. When the last uniform had been presented, President Johnson gave no indication as to whether he liked or disliked the new appearance of Park Service women, but simply said "Thank you" and inquired as to what the other women in the Park Service thought of the new uniforms. Although Riggs, as well as many other women didn't care for them, she very diplomatically told him that they were well received. The whole affair was very casual.

Riggs had arrived in civilian attire, but it had taken so long to complete the show that she was forced to wear the last uniform modeled in order to get back to the airport in time to make her flight. Even though the President hadn't shown much interest in the new uniforms, she was bombarded with questions from people in the airport as to what department or agency she worked for. No doubt the standard straw ranger hat and Park Service insignia on a uniform totally foreign to anything they had ever seen sparked this inquisitiveness.

It didn't take the women of the Park Service long to realize that the new uniforms were more fluff than substance. If anything they added to the woes of the women, not being as serviceable as those previously worn. The new uniforms were very stylish and chic, for duty in the offices and visitor centers, but in the field they were useless. They didn't hold up very well, and it wasn't long before all the enthusiasm of their introduction turned to ridicule. The public did not always realize that the women wearing these new uniforms were even in the Park Service. They still envisioned the ranger wearing forest green.

Not only were these new uniforms not suited for the field, under the right circumstances, they could be downright hazardous. Mary Bradford relates the story of being called out in an emergency, to help fight a brush fire. After the fire was out, she discovered that the heat had melted the hem on her dress.

The question of the badge also resurfaced. Now more than ever, with the women wearing a uniform foreign to anything the public was used to, they felt in need of a badge for recognition and to illustrate their authority. However, the same old issue of the fabric of the uniform not being able to support the heavy badge confronted them.

In 1972, some of the Western parks, notably Mesa Verde and Nez Perce, attempted to remedy this situation by contracting to have small, light-weight versions of the regulation badge made. This solved the weight problem, only to have a new one arise.

Instead of providing the desired credibility, the public thought the new badges were "cute", some even asking where they could be purchased, thinking they were souvenirs for children. Washington also frowned upon the issuance of the new badgettes and requested their recall. The short-lived experiment ended with the badges being turned in and removed from park property books.

In the summer of 1973, realizing the impracticability of the "A line" uniforms for performing even routine ranger duties, several of the women seasonals, Marilyn Hof and Lyndel Meikle among them, at Yosemite National Park, ordered "men's" uniforms from Alvord & Ferguson's in Merced, California. Meikle thought that a green ascot would look better than a tie on the ladies, an idea that didn't command too many followers. Lynn H. Thompson, then superintendent at Yosemite, photographed the two women in their new uniforms and forwarded the pictures to Washington.

In the meantime two of the summer seasonals who were offered winter employment at Everglades National Park because of their good work record, tendered their resignations out of concern that they would not be issued badges and would be required to wear the women's dress uniform. This incident, along with the Yosemite photographs and no doubt other complaints, prompted the Service to consider revising the uniform regulations covering women.

1974: A Turning Point

This change occurred the following year. Unrealized at the time, though, an extremely important battle for equal rights had just been won.

1974 saw the uniform change once again, although not entirely as the women had desired. The new uniform was to still be the "A line" style of double-knit polyester, although now it was to be dark green. Some women quickly christened it the "McDonald's" uniform because it reminded them of those worn by fast food workers.

Undoubtedly to placate some of the dissatisfied women in the field, an optional uniform was added. This was in essence the standard men's uniform, with a couple of exceptions.

In some of the parks (notably Yosemite), women had already started wearing this uniform the year before, but it took William Henderson, acting director, Southeast Region, to start the equality ball rolling. He suggested to Washington that women, when working with their male counterpart and performing equivalent work, should be allowed to wear the traditional uniform. Upon reviewing the situation, John Cook, at that time in charge of park operations in Washington, went one step further and directed there be only one uniform for both men and women. He also recommended the Uniform Regulations include a skirt for those women that preferred it.

Although written in October of 1977, it wasn't until the Spring of 1978 that the long awaited uniform regulation change came through, authorizing the women to wear the same gray and green, in all of its configurations, as their male counterparts. The only differences were that the women were to wear a cross tie instead of the four-in-hand, and they had the option of wearing a skirt. Along with this, for the first time, they were authorized to wear the complete assortment of special duty clothing.

Supply problems plagued implementation, but the threat of a class action lawsuit by female employees finally spurred the agency to resolve lingering obstacles, and two years after the 1977 order, women at last had a right to wear all the same uniforms and accessories as their male counterparts, in all its variations.

NPSART - Gilbert B. Cohen, artist -HFC/ARM#GR-0002-15 thru 19

This article is an abridged version of a longer piece. For additional information, footnote citations and more images, read the longer version of this article.

Last updated: June 16, 2020