Last updated: January 16, 2018

Article

Bay Area Architecture

Daguerreotype by J. M. Ford, courtesy of City of Santa Clara

While idyllic images of California architecture usually involve Mediterranean red tiled roofs and white stucco walls or a rustic, sprawling ranch, true California architecture is more complex. Early Spanish and Mexican occupation of the area that is now California had a significant impact on the built environment that has evolved in the State over the past two centuries, but it was not the only influence. Eastern architects also migrated with the gold-seeking 49ers. These architects and east-coast immigrants brought with them contemporary Victorian tastes. Over time, other factors have influenced the architecture of the San Francisco Bay area, which today contains a fascinating variety of commercial, institutional, and domestic buildings.

Unlike other states, there are no architectural remains in California of construction that might have taken place prior to European colonization. The traditional architectural practices of both the Spanish, and later Mexican, immigrants were easily adopted in Alta California because of the moderate climate and abundance of the familiar adobe material. Adobe refers not only to the mud building material, but also the structure that was created with it. Adobe was the prevalent material used in the Bay Area through the gold-rush period, and there were no wooden-frame buildings in San Francisco until the 1830s. The building program of the Spanish colonialists began in 1769, with the establishment of the first mission (San Diego de Acalá) of what was to become a chain of 21 missions along the California coast. Construction of the missions was undertaken by the padres (monks) of each mission. The Santa Clara mission, the eighth mission established, was the work of a padre who had built extensively in Mexico for Father Junípero Serra, the influential Franciscan missionary who established nine early missions in California. Most missions were adobe with tile roofs with wide eaves to protect the walls from rain. Not long after the transfer of California to Mexican control in 1822, the Mission system was secularized and many of the missions were abandoned, plundered for building materials, and deteriorated quickly.

Photograph by Shannon Bell

While the Franciscan missionaries were building their religious structures, secular construction was also taking place in the campaign for California settlement, specifically in the form of presidios, pueblos, and ranchos. The missionaries were accompanied by soldiers who established four presidios, or forts, from 1769 to 1782 in San Diego, Monterey, San Francisco, and Santa Barbara. Like the missions, the presidios were U-shaped fortified areas with an internal plaza. After the San Francisco presidio was established, the first of three pueblos, or towns, was also founded. The San Jose pueblo was established in 1777, followed by Los Angeles (1781), and Villa de Branciforte (1797). Pueblos were intended to increase the food supply and supplement the defenses offered by the presidios. The pueblos were also planned around a central plaza, included a chapel and other municipal buildings, covered walkways, adobe homes, and pastures. With time, the soldier-settlers became more interested in establishing their own ranchos outside of the presidios and pueblos. Secular society thrived around the pueblos and ranchos. These early Spanish settlers adopted the unofficial title of "Don" to distinguish themselves from those settlers arriving after Mexican independence. During this period the ranchos of the Dons were single-story, flat-roofed adobes, often without floors, chimneys, doors, or windows. Most flat-roofs of the ranchos, pueblos and presidios were asphalt or thatched.

Photograph from National Historic Landmarks collection

In the 1830s a new style of architecture evolved in California that was a unification of these early Spanish-Mexican building practices and the New England architectural traditions that were familiar to the increasing number of American immigrants. The first of these buildings was constructed by Thomas Larkin in the trading port of Monterey, after which numerous Monterey Colonial houses were modeled throughout the State. Larkin introduced strong redwood timber framing that could support a second story, but adopted the adobe walls, and attached a two-story veranda to protect them. The Larkin House also introduced the eastern floor plan of two rooms on either side of a central hall. Today, the Jose Maria Alviso Adobe is the only remaining example of this prevalent style in the Santa Clara Valley and San Francisco Bay Area.

Photograph by Judith Silva, courtesy of the City of Santa Clara

With the massive immigration to California that occurred during the mid-19th-century gold rush, some adopted the use of the abundant adobe building material before the establishment of lumbermills. Gold country was often a myriad of makeshift tents and some prefabricated woodframe shacks. But as soon as milled lumber and skilled carpenters were available, architectural styles popular throughout much of America during the last half of the 19th century were appearing in California as well. Among the gold-seekers were trained architects who established practices in California after gold-fever had subsided. They designed many sophisticated buildings in San Francisco, established a professional journal in the 1870s, called The California Architect and Building News, and a professional society by 1881. In contrast to these professionally-trained architects, a larger group of self-trained designers and carpenter-builders were also contributing to California's built environment, and designed the majority of Northern California homes. They depended heavily on popular design handbooks, and initially continued the Classical and Gothic Revival styles they were familiar with from the east and mid-west. From the 1860s through the 1870s, the vertical forms and asymmetrical floor plans of the Italianate style were popular. The Landrum House in Santa Clara is a hybrid example of these popular Gothic Revival and Italianate motifs. For the last three decades of the 19th century, Californians embraced the variety of decorative details found in the Victorian period, particularly Queen Anne ornamentation, such as that seen at the Charles Copeland Morse House, as this style easily made use of the abundance of native redwood. Examples can also be seen of Stick, Eastlake, Richardsonian Romanesque, Shingle, and the Renaissance Revival styles.

Photograph by Judith Silva, courtesy of the City of Santa Clara

Mission Revival, popular all over the country after its introduction in 1893 at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, was particularly attractive to Californians looking for a simpler regional architecture. Romantic ideals of the Spanish-Mexican colonial period were prevalent, if not unfounded, and most every California town erected a red-tile, white stucco Mission Revival building often with neo-Moorish towers and round arches. Instead of adhering to early-19th century colonial California examples, the style was based more on Mediterranean traditions, as exemplified in the elaborate Villa Montalvo or the Hayes Mansion. These architectural motifs experienced renewed popularity throughout California, and the entire country, from the late 1910s through the 1930s as the Spanish Colonial Revival.

Photograph by Judith Silva, courtesy of the City of Santa Clara

It was in Northern California that a new building material, reinforced concrete, was developed by Ernest Ransome, who constructed the first reinforced concrete building in America, the Arctic Oil Works, in San Francisco in 1884. Two decades later, the 1906 earthquake centered under San Francisco had a devastating effect on the entire Bay Area. Reinforced concrete became widely used thereafter to construct earthquake-safe buildings. San Jose's first "skyscraper," the Bank of America Building, was built in 1926 and is one of the first earthquake-proof buildings in the area. After the quake, damaged Victorian and Romanesque commercial buildings were generally replaced by popular 20th-century style buildings, such as Edwardian and Neo-Classical. The streetscape of Santa Clara Boulevard between Third and Fourth Streets in the San Jose Downtown Historic District is representative of this immediate post-earthquake design.

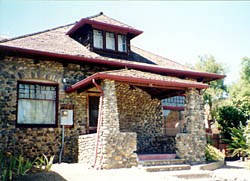

A new architectural ideal was also being embraced by many Californians in early 20th century--one which valued hand crafts over the machine-made, stained rather than painted wood, and the principle that "nothing is beautiful that is also not functional." One realization of these ideals was the Craftsman bungalow, a house form that was typically one to two stories with gently pitched broad gables, one large gable covering the main portion of the house and often a second, lower gable, covering a porch. Equally important was the interior arrangement of space, which eliminated hallways to create open floor plans and incorporated stained woodwork throughout. Californians were particularly receptive to craftsman ideas of integrating the house with its natural surroundings, possible, in part, because of the mild California climate and abundance of natural materials. The bungalow has been referred to as California's first architectural export, variations of which were adapted by communities around the country. Examples such as the Charles Wagner River Rock Bungalow can still be seen throughout the Bay Area today.

Photograph by Judith Silva, courtesy of the City of Santa Clara

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, many professional architects were making their imprint on Northern California. Bernard Maybeck was one of several well-educated eastern architects to arrive in San Francisco in the 1890s. Maybeck joined the firm of A. Page Brown, San Francisco's leading pre-earthquake architect. By 1894 he had established a private practice in Berkeley, and began teaching at the University of California in Berkeley. Maybeck drew upon a wide variety of stylistic and regional inspirations, characterized by the use of shingles and stained wood. Maybeck's clients were cultural leaders and professors, and his Sunbonnet House in the Professorville Historic District in Palo Alto is typical of his work. He was the center of the Craftsman movement in the Bay Area and an important mentor to a number of young architects, such as Julia Morgan, one of the nation's first prominent female architects. A native Californian, Morgan attended the University of California and the Ecolé des Beaux-Arts, after which she returned to the West Coast and soon established her own practice in San Francisco at age 32 in 1904. During her 46-year career, Morgan designed nearly 800 buildings, including homes, schools, churches, women's clubs and other small institutional buildings throughout California and the West, but primarily in the San Francisco Bay area. Her buildings incorporated practicality, convenience and elegant simplicity. Along with Maybeck, Morgan helped formulate a style specific to the Bay Area which blended the building with the landscape, used wood for both interior and exterior finishes, incorporated numerous windows, courtyards, porches and large spaces that conveyed an open, natural, informal feel.

Photograph from National Historic Landmarks collection

Frank Lloyd Wright, one of the most enigmatic and influential architects of the 20th century, was also practicing in Northern California. Wright experimented with an innovative hexagonal design in his Hanna Honeycomb House. Patterned after the honeycomb of a bee, the house incorporates a series of six-sided figures in its plan, terraces, and built-in furnishings. However, his Prairie style house, touted as the first indigenous American architecture and the basis of much modern design, had far wider reaching influence in California. Wright's typical prairie house was long and horizontal in form with low-pitched hip roofs and wide projecting eaves, a central portion of the house rising slightly higher than the flanking wings, with banks of windows and wide-open floor plans and large central hearth.

These American ideas of openness and the close relationship between interior and exterior spaces paved the way for a great deal of experimentation in architecture. By the mid-20th-century post-World War II building boom, Wright's ideas were meshed with those behind the bungalow and Modern movement into the emerging suburban ranch house. Throughout the Santa Clara Valley, acres of farmland were replaced by suburban developments, many of them dominated by the ranch house, often seen as a reflection of the informal nature of Western culture. These single-story, horizontal houses with low pitched gable roofs, rambling floorplans, and attached garages were like much of California's architecture--an evolution and combination of earlier styles. And like the bungalow, the Western Ranch house permeated suburban development around the country as the influence of California's architectural frontier spread beyond the boundaries of the golden state.