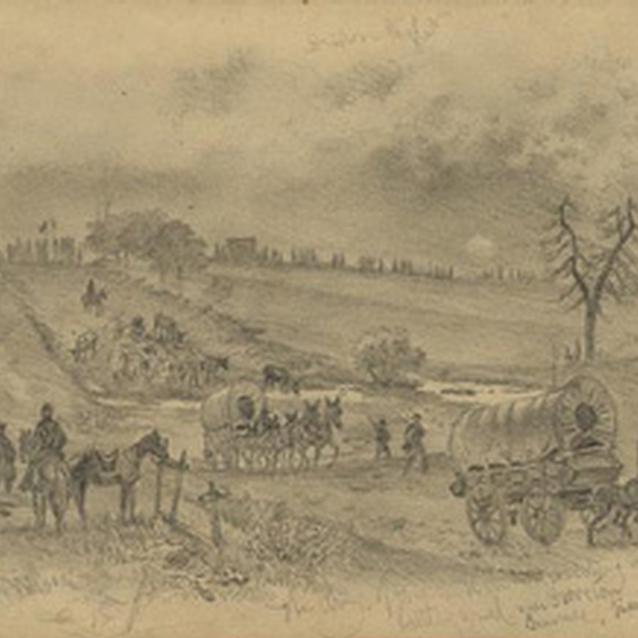

Jackson left Gen. Richard Ewell's division to cover their rear at Bristoe and moved with the rest of his command to Manassas Junction. There then followed a scene of feasting and plunder the like of which has seldom been witnessed. Knapsacks, haversacks, and canteens were filled with articles of every description. Added to vast quantities of quartermaster and commissary supplies were innumerable luxuries from sutler stores, including expensive liquors and imported wines. An eyewitness wrote, "To see a starving man eating lobster salad & drinking rhine wine, barefooted & in tatters was curious; the whole thing is indescribable." What could not be eaten or carried away was finally put to the torch. With the destruction of these supplies one of the chief objectives of the campaign had been accomplished.

"Jackson's first order was to knock out the heads of hundreds of barrels of whiskey, wine, and brandy. I shall never forget the scene. Streams of spirits ran like water through the sands of Manassas" Major W. Roy Mason

Manassas Junction and Bristoe Station (Kettle Run)

Library of Congress

Advised of the disruption to his supply line, Pope immediately saw an opportunity to crush Jackson in his rear. Ordering his forces to abandon their strong positions along the upper Rappahannock, Pope planned to concentrate his entire strength against Jackson. McDowell's and Sigel's corps, together with Reynolds' division were to move to Gainesville, while Reno's corps, with Kearny's division of Heintzelman's corps, was to concentrate at Greenwich. By these dispositions Pope hoped to intercept any reinforcements coming to Jackson by way of Thoroughfare Gap. With Hooker's division of Heintzelman's corps, Pope moved along the railroad toward Manassas Junction.

Pope did not realized it, but his actions were exactly what Robert E. Lee had hoped for.

Jackson had been sent behind Pope's lines in a deliberate attempt to draw the Union army away from the Rappahannock and give the Confederates a better opportunity to strike Pope under more favorable conditions. Following the same path Jackson had taken, Lee put Longstreet's wing in motion. His object was to reunite with Jackson before Pope could bring the full weight of his army against him. On the afternoon of August 27th, Hooker attacked at Bristoe. After stubbornly resisting Hooker's advance, Ewell retired in textbook fashion to Manassas where he rejoined Jackson. Pope, now convinced that Jackson's entire command was at Manassas, issued new orders for his army to converge there. He then boasted, "If you will march promptly and rapidly at the earliest dawn of day upon Manassas Junction we shall bag the whole crowd."

During the night, however, Jackson abandoned the junction and took a position north of Groveton, near the old Manassas battlefield, to await the arrival of Lee and the rest of the army. An unfinished railroad grade ran directly in front a ridge and the alternating cuts and fills of the railroad grade offered a ready-made fortified position with excellent cover and concealment for Jackson's men.

When Pope arrived at Manassas Junction at midday on the 28th, he found it deserted and reduced to a smoldering ruin. During the afternoon Confederate stragglers picked up on the road to Centreville suggested that Jackson was trying to escape in that direction. Pope dispatched new orders to his subordinates, then converging on the roads to Manassas, directing them instead to Centreville. These new orders reached Gen. Rufus King's division of McDowell's corps about 5:00 p.m., shortly after it had passed through Gainesville and had turned southward from the Warrenton Turnpike for Manassas. King counter-marched his column back to the turnpike and turned it eastward toward Centreville. The head of this Federal column reached the little crossroads community of Groveton totally oblivious of the fact that they were being watched

Brawner Farm (Battle of Groveton)

Library of Congress

The first blows of the Second Battle of Manassas were struck in the fading hours of daylight, August 28th. The action was officially termed the "Engagement near Gainesville," though sometimes it is referred to as Brawner Farm or the Battle of Groveton.

About 5:30 p.m., Jackson looked down on the Warrenton Turnpike and observed Gen. King's division advancing eastward toward Centreville. To allow them to pass might well forestall the main objective of the campaign, which was to bring Pope to battle before McClellan's reinforcements could reach him. Yet to attack now would likely bring down the weight of Pope's entire army upon his troops before Longstreet could join him. Jackson hesitated only a moment. Then with the softly spoken order, "Bring out your men, gentlemen," he hurled units of Gen. William Taliaferro's division, later reinforced by Ewell's troops, at the "Black Hat Brigade" of Gen. John Gibbon.

Fighting with valor that would soon change their name to "The Iron Brigade," Gibbon's four regiments advanced onto the Brawner Farm. There, supported by two regiments of Gen. Abner Doubleday's brigade, they held a line within 100 yards of five Confederate brigades. For two and a half hours, the fighting continued without cessation. As darkness closed upon the field, Gibbon slowly withdrew. The Union side suffered 1,100 casualties out of a fighting force of 2,800. The famous "Stonewall Brigade" of Virginians was reduced to 350 men after beginning the fight with 635.

Thoroughfare Gap

Library of Congress

Earlier that afternoon, about 3:00 p.m., G.T. Anderson's brigade, leading Longstreet's column, reached Thoroughfare Gap in the Bull Run Mountains to find their way blocked on the eastern side of the gap by Federal infantry and artillery under Gen. James B. Ricketts. McDowell had taken the liberty of sending Ricketts' division to the gap upon being alerted by his cavalry of Longstreet's approach. After initial skirmishing at the eastern entrance to the gap, Anderson deployed his Georgia regiments on the steep slopes of Mother Leathercoat Mountain, behind Chapman's Mill on the north side of the gap. Henry Benning moved the Georgia troops of his brigade into position on the high ground of Pond Mountain south of the gap. For several hours they successfully resisted the probes made by Ricketts' division. Possession of the mill changed hands three times. In an attempt to break the impasse, Evander Law's Confederate brigade made a flanking maneuver, scaling the steep cliffs of Mother Leathercoat Mountain. Law's skirmishers ultimately gained a foothold on the flank of Ricketts' artillery about sunset. With his flanks in peril, Ricketts disengaged and fell back to Gainesville.

As the battle waned, Longstreet sent Wilcox's division by way of Hopewell Gap in an effort to outmaneuver his opponent. Wilcox's column reached Antioch Church, east of Hopewell Gap, about midnight, long after Ricketts had withdrawn. That night, without informing Pope of their intentions, King and Ricketts independently decided to move towards Manassas Junction.

The fight at Thoroughfare Gap was confined to a relatively small area due to the topography of the area. Limited numbers were engaged on both sides. Federal casualties were roughly 90 killed and wounded while Confederat losses were not more than 25 men. Despite the small scale of this battle, it had a decisive impact on the campaign as it enabled Longstreet to reunite with Jackson the following day.

Part of a series of articles titled The Vortex of Hell.

Previous: The Confederates Take August

Next: Constant Attack

Last updated: February 4, 2015