Nearly 80% of Denali's annual visitors (~400,000) see a grizzly bear during their visit. Given the volume of visitation, high likelihood of seeing a grizzly bear, and the potential link between the viewing experience and support for conservation, this represents a tremendous untapped potential to bolster wildlife conservation at Denali.

NPS Photo / Emily Brouwer

Locations such as Denali (DENA) rely on the link between visitors’ wildlife viewing experiences and subsequent support for conservation. However, park managers and interpreters often need empirical data to identify visitors’ perceptions towards conservation issues. Park management and interpretation often relies on understanding an audience’s perceptions and experiences, particularly related to site-specific resources, such as grizzly bears at DENA (e.g., Beck and Cable 2011; Manning, 2011). Similar to interpretation, many public outreach initiatives use an audience’s existing perceptions and experiences as a foundation to design strategic pro-conservation messages (Center for Research on Environmental Decisions 2009). Environmental policy decisions also require an understanding of constituents’ underlying perceptions (Jacobson 1999). Without understanding visitors’ grizzly bear viewing experiences and levels of caring about the grizzly bears, wildlife interpretation and management decisions may be misinformed. Therefore, during the summer of 2013, researchers investigated DENA visitors’ commitment to grizzly bear conservation to inform park management, interpretation, and outreach. Specifically, researchers and managers sought insight into (a) the emotional impact of the grizzly bear viewing experience, (b) visitors’ levels of conservation caring, and (c) their willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors towards grizzly bears at the park. These constructs and their measurements are discussed in the following section.

Methods

On-site questionnaires were administered to DENA visitors in the summer of 2013. Visitors were approached at the Wilderness Access Center and asked to complete the questionnaire after finishing their bus tour on the Denali Park Road. Researchers used a stratified random probability sampling approach diversifying across types of bus tours (e.g., distance, price, time spent) to ensure a representative sample.

NPS Photo / Emily Brouwer

The questionnaire assessed visitors’ perceptions of grizzly bears including the emotional impact of the grizzly bear viewing experience, willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors towards grizzly bears at the park, and their levels of conservation caring towards grizzly bears as a species (see Table 1 for items used to measure these constructs). The emotional impact of the grizzly bear viewing experience captured the on-site experience and its contribution to visitors’ emotional connections to grizzly bears.

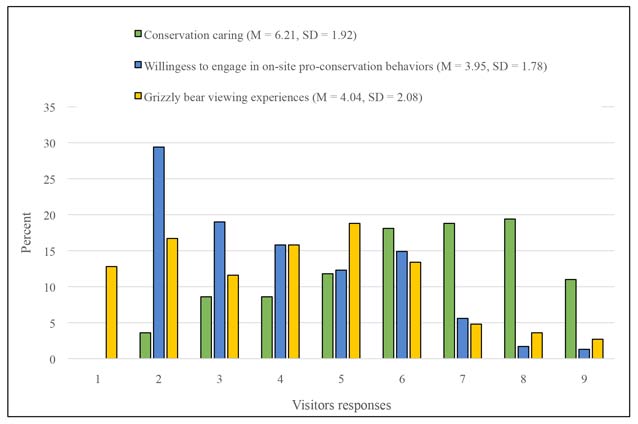

Visitors’ willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors towards grizzly bears at the park was measured using questions evaluating visitors’ likelihood to engage in park-specific conservations actions. Conservation caring was evaluated by asking visitors’ to report their level of affective (i.e., care about) and cognitive (i.e., care that) connection to grizzly bears as a species. Conservation caring differs from the emotional impact of the grizzly bear viewing experience because conservation caring measured the level of visitors’ connection to grizzly bears as an entire species and the impact of the grizzly bear viewing experience captured the contribution of on-site experiences to visitors’ emotional connection to DENA grizzly bears. All responses were measured on a nine-point scale, with higher responses (i.e., 7, 8, 9) indicating (a) a more emotionally impactful grizzly bear viewing experience, (b) a higher willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors towards grizzly bears at the park, and (c) a higher level of conservation caring.

After standard data cleaning and validating the measurements, descriptive statistics were calculated for each construct (Byrne 2008). Next, a K-means cluster analysis (Wu 2012) was used to group individual cases of visitors with similar patterns of responses to create manageable and highly homogeneous clusters that were statistically different from each other. For this study, visitors were categorized based on their levels of conservation caring and willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors towards grizzly bears at the park. Following this segmentation, researchers evaluated if these distinct groups of visitors differed in their emotional impact from the grizzly bear viewing experiences.

Results

Description of the Sample

A total of 472 visitors completed the questionnaire (89 percent response rate). The sample was evenly split between males (51.3 percent) and females (48.7 percent). The majority of the visitors (70 percent) reported a four-year college degree or graduate/professional degree. The visitor population at DENA was found to be fairly homogeneous in that white visitors comprised 83 percent of the sample. Fifty percent of the visitors reported more than $75,000 in annual household income. Approximately 18 percent of the sample was from Alaska, 68 percent of the sample was split between the remaining U.S. Census regions, and 13 percent were international visitors.

Table 1

| Constructs and Items | Mean (SD) | λ |

|---|---|---|

| Conservation caring | 6.21 (1.92) a | -- |

| Ensuring grizzly bear survival is my highest priority. | 5.66 (2.27) | 0.75 |

| My emotional sense of well-being will be severely diminished by the extinction of grizzly bears. | 5.39 (2.51) | 0.81 |

| My connection to grizzly bears has increased my connection to all wildlife. | 4.85 (2.40) | 0.79 |

| I will alter my lifestyle to help protect grizzly bears. | 4.62 (2.36) | 0.85 |

| I need to learn everything I can about grizzly bears. | 4.55 (2.21) | 0.85 |

| Willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behavior | 3.95 (1.78) a | -- |

| I would support entrance fees at Denali being $10 - $25 higher, if the extra money was used for the management of grizzly bears. | 5.02 (2.37) | 0.75 |

| I would write a letter/sign a petition to a government official supporting grizzly bears at Denali. | 4.10 (2.92) | 0.71 |

| I will donate up to $75 to help purchase bear-proof trash cans around Denali. | 3.41 (2.25) | 0.80 |

| I will provide on-going financial support to Denali. | 3.02 (2.26) | 0.87 |

| I will contribute up to $150 to support the on-going research of grizzly bears at Denali. | 2.99 (2.15) | 0.80 |

| Before my visit is over, I will sign up for a mailing/email to receive updates about grizzly bears at Denali. | 2.84 (2.26) | 0.80 |

| I will become a member of an organization committed to protecting grizzly bears at Denali, within the next 6 months. | 2.72 (2.04) | 0.87 |

| Impact of the grizzly bear viewing experience | 4.04 (2.08) a | -- |

| I spent time discussing grizzly bears with others in my group. | 4.44 (2.71) | 0.78 |

| I understood their (grizzly bears) behaviors. | 4.18 (2.57) | 0.81 |

| I understood their emotions. | 3.31 (2.41) | 0.96 |

| I felt empathy for them because of their emotions. | 3.20 (2.35) | 0.81 |

Table 1. Measurement performance and items for conservation caring, willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors, and the grizzly bear viewing experience at Denali National Park and Preserve (DENA).

Notes: All items rated as agreement on nine-point scale; 1 = completely disagree; 9 = completely agree; a = estimated construct mean; all fit indices derived from robust statistics; CFI = comparative fit index; λ = standardized factor loading; NNFI = non-normed fit index; RHO = adjusted Cronbach’s alpha; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; SB χ2 = Satorra-Bentler Scaled Chi-Square; SRMR = standardized root mean squared residual;* p < 0.05. Each of the model fit indices has acceptable levels of good fit: CFI > 0.90; NNFI > 0.90; RMSEA < 0.08; RHO > 0.70; SRMR < 0.1; (Byrne 2006; Kline 2011).

Visitors’ Levels of Conservation Caring, Willingness to Engage in On-Site Pro-Conservation Behaviors, and Grizzly Bear Viewing Experiences at the Park

The psychometric properties for conservation caring, willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors, and the emotional impact from the grizzly bear viewing experience achieved desirable and acceptable levels, indicating that these constructs were measured appropriately (Table 1). The majority of visitors (67.3 percent) reported high levels of conservation caring (Figure 2). In contrast,

76 percent of visitors reported a low willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors. Visitors’ emotional impact from a grizzly bear viewing experience was moderate and relatively dispersed across response categories (Figure 2).

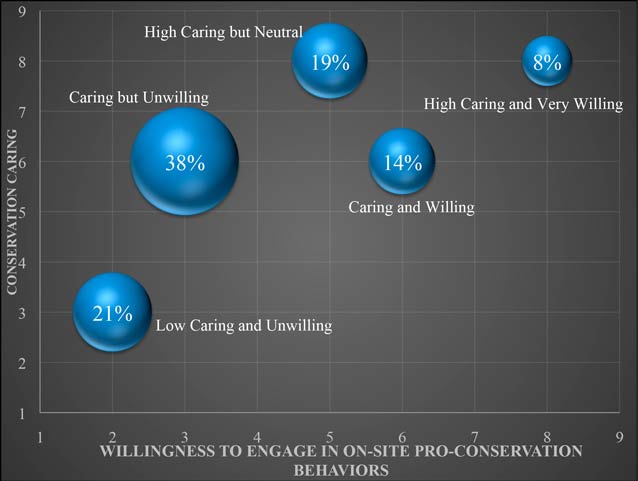

K-Means Cluster Analysis and Visitor Segmentation Groups To identify different groups of visitors with similar perceptions, the researchers combined the measures for conservation caring and willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors into a single model. Results indicate five significantly distinct groups of visitors exist based on their (a) levels of conservation caring, and (b) willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors. The largest group of visitors with similar perceptions (38.3 percent) is described as “Caring but Unwilling.” These individuals are characterized by a moderate level of conservation caring while also reporting limited willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors (Figure 3).

The next largest group, which comprised 20.5 percent of the sample, is described as “Low Caring and Unwilling.” This group is characterized by low levels of conservation caring and a low willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors. Next, the “High Caring but Neutral” group reported a high level of conservation caring and neutral levels of willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors. This group represents approximately 18.7 percent of the sample.

The “Caring and Willing” group comprised 14.4 percent of the sample and report moderate levels of conservation caring as well as moderate levels of willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors. The smallest group of visitors is described as “High Caring and Very Willing” (8.2 percent of visitors), which is characterized by high levels of conservation caring, and high levels of willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors.

These five visitor segmentation groups do not differ significantly in their past visitation to the park, age, gender, income, residence location, or education. However, these groups do differ significantly in respect to the emotional impact from their grizzly bear viewing experiences.

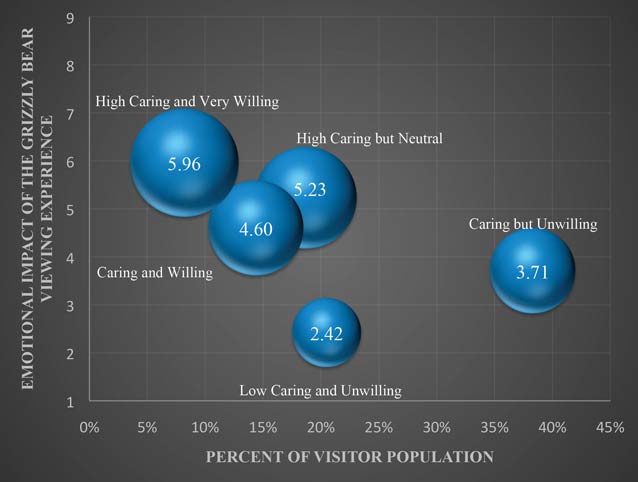

The Emotional Impact from the Grizzly Bear Viewing Experience

The emotional impact from the grizzly bear viewing experiences was found to be generally moderate and significantly different between the five segmentation groups (Figure 4). Visitors in the “High Caring and Very Willing” group reported the highest emotional impact from the grizzly bear viewing experience. Visitors who report a higher emotional impact from a grizzly bear viewing experience also report higher levels of conservation caring and higher levels of willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors (Figure 4). However, this represents only 8.2 percent of the total sample. Conversely, the “Caring but Unwilling” group represents the largest segment of the visitor population (38.3 percent) and visitors in this group report a moderate to low emotional impact from their grizzly bear viewing experience. These data suggest one of two things. First, visitors’ levels of conservation caring and willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors are partially a function of the emotional impact born from the grizzly bear viewing experience. Alternatively, visitors who already have higher levels of conservation caring and willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors before their DENA visit are more likely to have emotionally meaningful grizzly bear viewing experiences. Regardless, on-site wildlife viewing experiences with charismatic megafauna (e.g., grizzly bears) are potentially quite important when considering visitors’ willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors towards grizzly bears at DENA.

Discussion and Management Implications The purpose of this study was to gain insight into visitors’ grizzly bear viewing experiences, levels of conservation caring, and willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors towards grizzly bears at Denali National Park and Preserve. Results indicate that visitors have high levels of conservation caring but low levels of willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors. Furthermore, visitors with high levels of conservation caring and a high willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors also report emotionally impactful viewing experiences. Implications for these results are two-fold and affect visitor management as well as interpretation at DENA.

DENA visitors report low levels of willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors, which is potentially influenced by visitor management transportation policies related to use of the Denali Park Road (e.g., providing no public vehicle access, with the exception of designated overnight campgrounds). The transportation policies protect important resources and provide unique visitor experiences by requiring visitors to take a bus tour, walk, or bike the park road. The majority of visitors tour DENA on buses traveling into the park daily and hourly during peak season. The bus tours vary from four to eight hours, and visitors are typically arriving directly before and departing immediately after their bus tour—potentially providing limited time and schedule flexibility to consider engaging in on-site pro-conservation behaviors. This bus tour experience and consequential constraints potentially lead to low

levels of willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors. Additionally, an information deficit could

exist whereby visitors’ are unclear about opportunities to financially contribute or join an organization to support on-site pro-conservation towards grizzly bears at the park. Information deficits, constraints on time, and schedule flexibility may contribute to visitors reporting low levels of willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors. Interpretation, however, could highlight how on-site pro-conservation behaviors are mutually beneficial to grizzly bears and the visitor experience, as a possible solution.

DENA may be ideally positioned to provide links from conservation caring to on-site pro-conservation behavior because visitors’ report relatively high levels of conservation caring, and conservation caring has been shown to be a strong predictor of pro-conservation behaviors (Skibins and Powell 2013). Interpreters and park staff could strive to inform visitors through campaigns focused on understanding the importance of participating in on-site pro-conservation behaviors. Information could be tailored to each group

(Figures 3 and 4) describing how to contribute to grizzly bear protection in DENA and why it is important. For example, it may be advantageous to design specific messages to target the “Low Caring and Unwilling” (21 percent of

the sample). For this group, interpretation messages can stress the importance of conservation caring and on-site pro-conservation behaviors through providing specific behavioral outcomes such as organizations to join, volunteer openings, and adoption opportunities. Although it may

be difficult for park staff to quickly identify which visitors arriving at the park belong to a specific segmentation group, park staff can design specific messages that may attend

to each group’s characteristics derived from this study.

NPS Photo / Bob Winfree

Grizzly bear conservation at DENA may be fostered by drawing on specific elements of the grizzly bear viewing experiences. The majority of visitors (71 percent) are in three of the five segmentation groups that report moderate to high levels of conservation caring. For grizzly bear conservation, this means visitors’ report relatively high levels of affective and cognitive connection to grizzly bears as a species. The results from this study specifically link visitors’ high levels of conservation caring with high levels of emotional impact during grizzly bear viewing experiences. Therefore, by fostering emotional connection with grizzly bears during viewing experiences, DENA may be able to increase overall levels of conservation caring for grizzly bears in the park.

It is important for interpretation to nurture environments whereby visitors can connect with grizzly bears at an emotional level through safe and sustainable on-site viewing opportunities (e.g., avoiding human-bear conflict and providing visitor education). According to Manfredo (2008), “from an applied perspective, it is important to realize that emotional responses are at the heart of human attraction to, and conflict over, wildlife.” The results of this study suggest visitors emotionally connect most with grizzly bears at DENA when they have spent time discussing grizzly bears with others in their group, feel that they understand grizzly bear behaviors and emotions, and feel empathy for grizzly bears. Therefore, interpretation can help visitors explore, understand, and connect to DENA grizzly bears by connecting bear and human behavior and emotion. For example, many grizzly bear behaviors viewed during a visit may be similar to the human experience, and interpretation could highlight emotionally laden topics, such as the role of mothering in an offspring’s success. In practice, when viewing a sow with her offspring, time spent interpreting animal behaviors and connecting the observations to visitors’ lived experiences could increase levels of conservation caring and a connection to grizzly bears. Such increases may stimulate visitors’ willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation actions and consequentially targets the visitors (71 percent) who report moderate to high levels of conservation caring but low to moderate levels of willingness to engage in on-site pro-conservation behaviors.

Denali National Park and Preserve, with more than 400,000 visitors annually, has a unique opportunity to proactively link interpretation and park management

to on-site grizzly bear conservation. A prerequisite for effective wildlife interpretation and management decisions is knowledge of an audience’s existing perceptions and connections to particular species (Manfredo 2008). DENA has the prospect to improve conservation efforts by expanding on-site opportunities for visitor-based actions thereby bolstering grizzly bear conservation on public lands, provided there is an understanding of audiences’ perceptions of grizzly bear viewing experiences. Without fully evaluating the grizzly bear viewing experience and visitors’ perceptions, funds and management options may be ineffectively applied to grizzly bear viewing and grizzly bear interpretation strategies.

Author Note

The authors acknowledge and thank the Global Change and Sustainability Center at the University of Utah and the David C. Williams Fellowship for supporting this research. Additionally the authors thank Denali National Park and Preserve for their non-monetary support and assistance.

NPS Photo / Bob Winfree

References

Anderson, L., R. Manning, W. Valliere, and J. Hallo. 2010.

Normative standards for wildlife viewing in parks and protected areas. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 15(1):1-15.

Beck, L., and T. Cable. 2011.

The Gifts of Interpretation. Champaign, IL: Sagamore.

Byrne, B. 2008.

Structural equation modeling using EQS. New York: Psychology Press.

Center for Research on Environmental Decisions. 2009.

The Psychology of Climate Change Communication: A Guide for Scientists, Journalists, Educators, Political Aides, and the Interested Public. New York: Center for Research on Environmental Decisions.

Jacobson, S. 1999.

Communication skills for conservation professionals. Washington: Island Press.

Manning, R. 2011.

Studies in Outdoor Recreation: Search and Research for Satisfaction. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press.

Manfredo, M. 2008.

Who cares about wildlife: Social science concepts for exploring human-wildlife relationships and conservation issues. New York: Springer.

Skibins, J., J. Hallo, J. Sharp, and R. Manning. 2012.

Quantifying the role of the Denali “Big 5” in visitor satisfaction and awareness: conservation implications for flagship recognition and resource management. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 17(2):112-128.

Skibins, J., R. Powell, and J. Hallo. 2013.

Charisma and conservation: Charismatic megafauna’s influence on safari and zoo tourists’ pro-conservation behaviors. Biodiversity and Conservation 22(4):959-982.

Wu, J. 2012.

Advances in K-means Clustering. New York: Springer.

Zinn, H., M. Manfredo, and D. Decker. 2008.

Human conditioning to wildlife: steps toward theory and research. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 13(6):388–399.

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 14 Issue 1: Resource Management in a Changing World.

Last updated: August 12, 2015