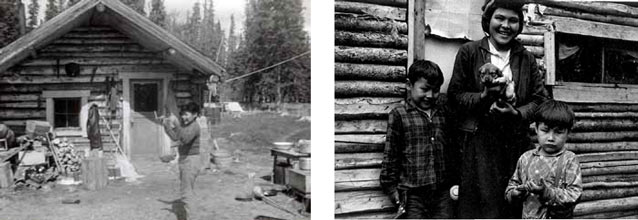

Courtesy Wilson Justin

I always thought that one could see forever if one could be friends with the steep shadows that drop quickly in the autumn mountains. There is a rhythm even in the silence that marks time in a way that could never be counted in the twisting electronic glare of captured light cast harshly against houses, or glass or steel.

Once turned, the trail is a different friend. A horse quickens his pace, the camp dog will bounce a bit, and the hunter feels for the moment a sense of senselessness. All is home on the trail whose call may be older than your clan but even then I can sense in the pull of the evening sky something more vast and more complete, just ahead or just around the corner or maybe next to the last lonely sun-caught rock on a distant peak.

I know I have heard forever but have I seen it? Which eyes would it have been? The Nabesna? Let’s see what it looked like then.

At six years of age I could only see the field lying just past the trees, and what seemed to me miles and miles of openness, reaching in a giant sweeping arc to the glacier, brilliant in the noon sun. It was only twelve miles away but I could see the broad, blue-white back snaking around the corner of the mountain in a sprawling curve that left nothing to chance, not in this eyesight or any other. The field would always have a fresh-blown feel to go with the enchanting scent of new flowers rooted in patches of purple, gold, and green.

The horses would shake their manes and long after in a faraway tone I would hear the bells which hung on their necks. Time comes in patches at six years of age and choppy even without the wind. I could not see downriver because of the trees and the creaking alders, but I could see upriver and it was a child’s forever right from the front of the cabin to the top of the sparkling glacier. It was there, it was always there. The noon sun would sear the river rocks and the heat waves would dance like dervishes first one way and then the other.

Courtesy Wilson Justin

Godfrey and I would run or walk or creep whichever was first in our minds, along the young spruce that curved up to the airfield. Very soon we would be missed and rugged brown faces would bob and crinkle in the heat behind us.

Our village had been pulled apart by forces that were light years from our comprehension and if there were some danger in the field, it was left to one of the four remaining adults to see to our safety.

I remember the evening songbirds soft and silky and the low deep murmur of the river across from us. Once night began to settle, the horses would drift down and camp out directly in front of our cabin (Figure 2), fearful of the occasional villainous grizzly ever mindful that there were still a few fighting dogs around the houses.

Figure 3 Courtesy Wilson Justin. Figure 4 Courtesy Al Clayton, Sr

The houses (Figure 3) were scattered along the trail leading to the watering hole three-fourths of a mile away and bearing southwest. The first little hut stapled together of small spruce and found nails belonged to my Aunt Lena (Figure 4). It was a teenager’s house thoughtfully built for one person. The next house (Figure 5) was of house logs cleaned and pressed to the ground with a fine axe

and fitted in a way that suggested permanence. Aunt Lena with four of her pack dogs pulling brought the beautiful timber to the site. Uncle Johnny edged the logs to form-fit arrow-straight and seal tight against the wind. It was labor in the name of duty. Three sisters and the brother put to a decency test on behalf of a semi-invalid elder.

Courtesy Wilson Justin

The house on the other side, a little bigger built to family size by Uncle Johnny and his brother-in-law. Again, pack dogs (Figure 6) built to power shoulder-deep snow aside were put to pulling in harnesses. In quick succession, Frank’s house and finally ours the last in line. Still caught, two other homes never completed, abandoned in mid-stride as it were when the village emptied out.

The next trail over, Shorty Frank took the shadows and hammered out a name there in the woods. Scattered here and there were tent frames, some of Northway, some of Chisana, but all empty and foreboding by the time I began to run the short footpaths between the non-neighbors. Even as new houses were left to gleam in the sun I could look up far past the trees and sudden flatness of the airfield and see right past the big outcrop of rock that defined the meeting room for the Jacksina River and the Nabesna River. It would always be there, the big white fortress of ice spilling light into the valley, resisting the night, never resting, never sleeping.

Godfrey went off to another village late that summer. His Dad came down and took him to the trail and then there was only the quiet wind and low murmur of the river. I stayed with my Aunt Lena. In the early morning she would take her 22 rifle and go to the hills for supper beckons early in our lives.

Courtesy Wilson Justin

I would climb up on a small platform of crossed saplings with a dog tied to the tree underneath and I would wait the day out until sometime late when my aunt would return from the snare line or the fish creek. The rare days when my aunt was able to stay close to the settlement, I would walk out to the field, and try as I might, I could not fathom the why of being the only two persons in a settlement still new. I did not know the lessons nor did I care that I was being tutored. The day would linger, the trees would sigh, eventually all the little critters would make their way to the dens or to the nesting places. I would look long at the falling sunlight and turn to the last cast of the glacier. It would be there; it would always be there.

The summer had not ended when I, too, was put to the trail. We were the last two out of Nabesna. My Aunt Lena, me, and her four pack dogs. I don’t remember the trip, but I can always feel the upwelling that comes when understanding finally sinks in that something had taken over and it was all really shadows. Somewhere down the trail we found a second home, or I guess I should say, another place to camp. But it wasn’t the same and I wanted to go back, and I did as I grew through the 1960s into the ’70s. I went back over and over for any number of reasons, but I never saw Nabesna again, in that light, of that summer under a glacier that promised to be with us forever, me and my faithful friend Godfrey. Jack came back and began painfully to rebuild his life from the sickness that put him into a sanitarium for a good while.

Courtesy Wilson Justin

He came back to the cabin built for him and stoically began measuring the years by the decades. The river rose and fell, told elsewhere in other stories of climate change and such. The first time I could look up the river again right out of high school in 1968, I could see a lot of brush and new growth along the airfield. I could also see clearly the glacier was crumbling, and with it all of the sounds of youth and freedom. The why of being left behind was never answered and never spoken. No one said anything about the glacier eating itself up finally to seep into the rocks under its once mighty wings. The river changed, too, from friend, then, to foe (Figure 7).

Between 1987 and 1997 I took the family back down to Nabesna (Figure 8). Each trip was a short burst of joy and freedom, but the leaving would be painful and gasping. The glacier was long gone and so I finally quit going back to where it was where I was born, and where my blood runs so deep.

Courtesy Wilson Justin

I stayed in the mountains after high school, close to the ice that filled all the peaks and all the meadows under the ridges. I grew to be a horseman (Figure 9) and I could tell what the weather was going to be like days ahead of it happening. I grew to be one with the sounds of the mountains and moved under the late autumn full moon with the ease of a wolf passing amongst the shadows. But each decade the ice was less.

When finally the last of the seven-thousand-foot peaks opened itself to the blue skies, I found myself no longer willing to be out there. I didn’t know why then but I knew what had passed was more than what men would know. There were a few times that I did go back. During a week’s worth of riding the old trails in 1993, the immense loneliness stayed with me every step of the way. I returned again in 1997, but that time I came short. After three days, I turned towards home and left it at that.

Courtesy Wilson Justin

Now that all the horses are gone and there is no chance of covering those high mountain trails ever again, I sometimes wonder if forever didn’t come too soon. Maybe I should have been five years old and then jump to seven years old and skip the summer in between. And so, I turn eyes now and then to distant peaks and think, how could the wind not have told me I would see footsteps of forever and not know that I did? Our trails are still out there (Figure 10).

Our songs still linger in the trees, our laughter can still be felt in the shift of the noon sun, but how did I miss it even when I was right there? So as the shadows steep in the quiet of the pastures and stop at the edge of the ravines, I can look back and I can still see that six-year-old sometime on the edge of the trees and sometimes on the corner of house. But he always is looking away and I cannot, although I try, to see what it is he is looking at.

Wilson Justin is an Athabascan who was born in 1950 in Nabesna, Alaska. The family moved to Chistochina in 1957, but he continued to spend summers at Nabesna. They then moved to Mentasta in 1959 so Wilson could attend school there. Wilson grew up in a traditional subsistence lifestyle, hunting, trapping and fishing in the Nabesna and Chistochina areas. He attended high school in Fairbanks and Anchorage, and graduated in 1968. From the 1960s until the mid-1980s, Wilson worked for the family business as a hunting guide in the Wrangell Mountains. He has been active in representing his community around the state in social, cultural and political matters.

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 13 Issue 1: Wilderness in Alaska.

Last updated: October 29, 2021