I arrived on Amchitka Island in the early spring. The island was covered with fog; everything looked gray. Puffins flew in and out of burrows; gulls called as we left the ship. The quiet of this place was a bit unnerving and it felt wild to be there. Merry Maxwell

USFWS Photo

Amchitka Island was used by the Aleuts for more than ten thousand years following their migration from Asia over the southern end of the Bering Land Bridge (Merrit and Fuller 1977).

The Aleuts depended on marine resources for their survival in the rich Aleutian environment where upwelling and deep turbulent mixing created waters rich with nutrients. In 1741, Russians discovered the islands and began to exploit these resources, including the Aleuts. They dominated the area until 1867 when the United States purchased the State of Alaska, including the Aleutian Islands.

The Aleutian Islands have always been recognized for wilderness qualities. These far-flung islands are home to millions of birds (Figure 3); many evolved where only aerial predators like eagles threatened their young. As exploration and fur trade activities continued, some people began to realize the very real threat to the fragile island ecosystems.

To protect the ecological value of these islands the Aleutians NIslands Reservation was established by Executive Order 1733 signed by President William H. Taft on March 3, 1913 (Department of the Interior 1973).

The reservation was originally established as a preserve and breeding ground for native birds, for the propagation of reindeer and fur bearing animals, and for the encouragement and development of fisheries. In the executive order establishing the reservation, a subordinate paragraph included the following phrase: “the reservation shall not interfere with the use of the islands for lighthouse, military or naval purposes.”

USFWS Photo

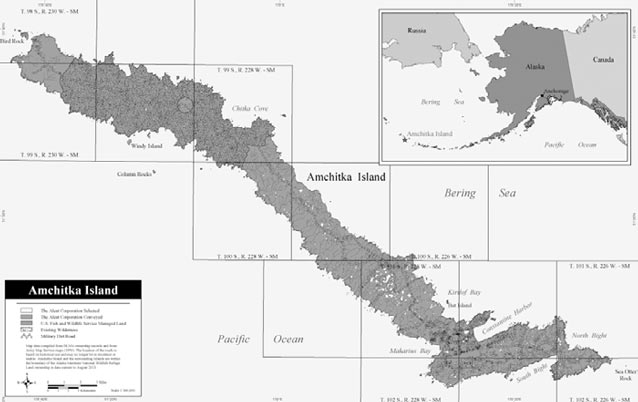

Amchitka Island is the largest in the Rat Island group, and is about forty miles long and 4.5 miles wide with lowlands on the eastern side and highlands on the western side. Because of its extreme western location, Amchitka and other islands in the Aleutians became important strategic defense posts during WWII, and later during the Cold War were important listening posts.

A History of Disturbance and Violence

During the spring of 1942, the American Doolittle raid on Tokyo raised the Japanese army’s interest in American air bases on the Aleutian Islands (Chandonnet 2008). This resulted in the subsequent Japanese occupation of Kiska, Little Kiska, and Attu Islands. Amchitka suddenly became a vital forward base for defense of the Aleutians and recapture of Japanese-occupied islands, and to this end, infrastructure for more than sixteen thousand troops was constructed on the island. The military continued using Amchitka Island following the war for more than seven years (Merrit and Fuller 1977) and officially pulled out in 1950, but a legacy of military use remains (Figure 4).

USFWS Photo

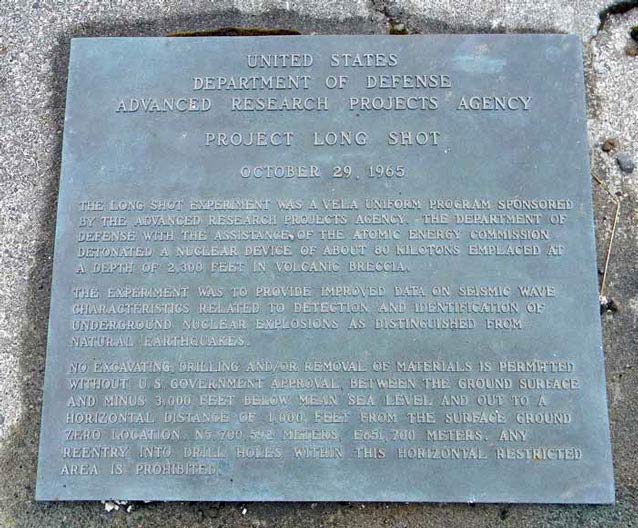

More was in store for this island strategically located near Asia. In 1951, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and the Department of Defense began using Amchitka for underground nuclear testing. Three nuclear tests were conducted on Amchitka. The first (Long Shot, eighty kilotons) (Figure 5) was to differentiate seismic signals generated by underground nuclear tests. The second test (Milrow, 1.2 megatons) was a calibration test to test safety (O’Neill 1994). The third and final test (Cannikin, 5 megatons) was the largest underground nuclear test in U.S. history. The blast from Cannikin lifted the ground more than twenty feet and was equal to about four hundred times the power of the Hiroshima bomb, shifting the ground and killing animals and birds violently (Rausch 1973). The uplift and following subsidence created a lake over the blast area. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game reported that seven hundred to two thousand sea otters were killed by pressure changes created by the blast (Kohlhoff 2002).

"In 2011 I arrived at Amchitka with a party of ten from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Figure 6), University of Alaska, Department of Energy, S.M. Stoller Corporation, Aleutian and Pribilof Islands Association, Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation, and the Argonne National Laboratory. We were on island to test the waters…literally.

We planned to test a small lake downstream from an abandoned Navy sewage lagoon known to have polychlorinated biphenyls or PCBs in it; sample sea creatures, wildlife, and plants for plutonium and uranium associated with nuclear testing, and test the waters around Amchitka for tritium which might indicate leaks from the underground blast chambers. My personal goal was to visit the designated wilderness area of Amchitka Island."

USFWS Photo

The Aleutian Islands Wilderness Area, (1,395,357 acres) was proposed in 1974 in recognition of unique values of the Aleutian Islands. When Amchitka was considered for wilderness three parcels were withheld for possible defense purposes. These areas included the most southerly and northerly areas of the island, the highest point on the island and a road connecting the areas. In other words, the wilderness area would be surrounded by areas withdrawn for possible future military use, and a forty-two-mile road (Figure 7) would bisect it (Department of the Interior 1973).

USFWS Photo

Indeed, military use of Amchitka was not over. The Cold War (sustained military tension primarily between the Soviet Union and the United States) escalated in the 1980s and Amchitka was again a point of focus for the United States. The Navy built and maintained a prototype Relocatable Over-The-Horizon Radar (ROTHR) system in order to listen to the Soviet Union from 1991 until 1993 (Figure 8).

Cleanup and removal of supporting infrastructure began in earnest after 1993. Buildings were removed and runways were demolished or abandoned all together. Remarkably, the two-mile-long Baker Runway, built for bombers but never used, remains. Today, areas on the south end of Amchitka are still a concern for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, responsible for cleanup of Amchitka and other sites within the Aleutians Refuge, now part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge. These areas include landfills (Figure 9), unexploded ordnance and buried and surface fuel drums contaminating soils and the ocean as they disintegrate and product is released. Other contaminants remain in lakes and streams following abandonment of sewage lagoons and other supporting structures.

USFWS Photo

"On our last day on island we drive north through the wilderness area to check on a ROTHR site at the north end of the island. As we start up the hills to the west I see the Pacific Ocean in the distance, green and gold hills, and lakes reflecting in a shroud of fog and am struck once more by the stillness

of this place.

I am on a national wildlife refuge, in the middle of the Aleutian Chain and my first glimpse of the ROTHR site shocks me; I am staring at what I will later describe as a lost Mayan Village—a huge formidable black rock structure several stories tall. I turn away and spend an hour walking the black sand beaches, reflecting on the value of wilderness."

USFWS Photo

What Does the Future Look Like?

The Aleutian Islands are wild. This primeval state is the result of where these islands are located. Most of the Aleutians are inaccessible except by ship and are subject to violent seismic activity and extreme weather, and they see very few visitors. Established communities are small and isolated.

While restoration on Amchitka progresses and the refuge works with the military to clean up the island, the future for this island is still very uncertain. On Amchitka, the natural healing process has been threatened and disturbed in a profound way. The legacy of war and nuclear tests remains; the contaminants and rats introduced during this time may never be removed, forever changing the diversity of this island. Ecosystems can usually recover from naturally occurring disturbances but Amchitka may be irreversibly changed, preventing literal restoration (Coates 1996). The actions taken outside of the wilderness area of the island and the reservation made for future military use should bring into question the expense and efforts of cleanup and restoration. Will we restore it and allow it to be compromised again?

USFWS Photo

But the value of wilderness is more than a place. The wilderness experience is not determined solely by the naturalness of the habitat or the biological factors related to the land; it can also be determined by our experience as we interact with it. Wilderness is not an artifact or static place but a system where natural processes will assert themselves in an effort to heal and flow toward ecological balance (Elder 2013).

On my last day on Amchitka I walk and reflect on what we might learn from the history of this place. Could we consider our nation’s changing military capabilities and allow this island to return to its purpose as a refuge? Will future generations wonder if we did our very best to protect it?

USFWS Photo

The past use of Amchitka is complicated, violent, and disturbing, but I am hopeful. As I prepare to leave I walk on the dust of urchins, ground to fine gold and washing up on black sand beaches. I can still hear the music of life in this place, and the whisper of a promise we made to preserve wildlife and wilderness.

References

Chandonnet, F., ed. 2008.

Alaska at War 1941-1945, The Forgotten War Remembered. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

Coats, P., 1996.

Amchitka, Alaska: toward the bio-biography of an island. Environmental History Vol1 Issue 4 p 20.

Department of the Interior, 1973.

Draft environmental statement, proposed Aleutian Islands Wilderness, Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, US Department of the Interior.

Elder, J. 2013.

The Undiscovered County, John Elder on the wild places close to home. The Sun, issue 450.

Kohlhoff, D. 2002.

Amchitka and the Bomb, Nuclear Testing in Alaska. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press.

Merrit and Fuller, 1977.

The Environment of Amchitka Island Alaska, National Technical Information Center, Springfield, Virginia 22161.

O’Neill, 1994.

The Firecracker Boys. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Rausch, R., 1973.

Post mortem findings in some mammals and birds following the Cannikin test on Amchitka Island, US Atomic Energy Commission, Nevada Operations office, Las Vegas, NV.

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 13 Issue 1: Wilderness in Alaska.

Last updated: August 4, 2015