Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 19, Issue 1 - Below the Surface: Fish and Our Changing Underwater World.

Article

The Role of the Diamond NN Cannery in Interpreting the History of the Naknek River Fishery

THE NN CANNERY HISTORY PROJECT

Upriver

Located in the heart of Katmai National Park and Preserve (Katmai NP&Pres) is the 1.5-mile (2.4 km) Brooks River, a tributary of the Naknek River on the Upper Alaska Peninsula in southwest Alaska. Each summer, a stream of visitors from near and far flock to the river’s viewing platforms to witness one of nature’s most extraordinary scenes: The world’s largest concentration of Alaska brown bear catching with powerful jaws and claws the world’s largest run of sockeye salmon. The salmon, with primal, undaunted instinct, leap the six-foot (1.8 m) cascading Brooks falls, often sailing past the furry fishers, on a mission to complete their life history spawning the next generation of Naknek River sockeye salmon and also carrying needed marine nutrients inland.

Those who come to observe this renowned, spectacular setting, describe it as a visitor’s para-dise—an isolated, natural wonder where humans take a back seat (Birkedal 1993). But what most visitors to Katmai’s wild river do not realize is that those salmon, soaring over the Brooks falls and evading the clutches of the Brooks bears, are part of an escapement—or the proportion of fish allowed by Alaska state fisheries biologists to “escape” the commercial fishery to return to spawn in their natal streams, which directly links the Brooks River experience to the red salmon commercial fishery, down the Naknek River, in Bristol Bay. Unlike the Brooks bears, Bristol Bay gillnet fishermen must sit idle with dry nets, waiting restlessly until fish counts reach estimated spawning goals upriver before they are allowed to fish.

Historic evidence of the commercial salmon fishery abounds at Brooks, in the form of the defunct fish ladder, the old Bureau of Commercial Fisheries research laboratory and remnants of a weir that biologists once used to count sockeye salmon migrating to Brooks Lake. The drive to better understand the largest, most valuable and most sustainable sockeye salmon fishery in the world led biologists to ask questions about the Naknek River’s ancient run sizes, sparking decades-long archeological investigations that culminated in the designation of the Brooks River Archeological District National Historic Landmark (Ringsmuth 2013).

More than a foil to Brooks bears, the salmon serve as a cultural, historical, and physical conduit that courses through the 35-mile (56 km) Naknek River, from its headwaters to its outlet into Bristol Bay. The salmon escapement moves beyond park boundaries, and places Katmai’s fish story in the larger historic context of the canned salmon industry and ties the natural drama of the Brooks River to the global story taking place downriver.

NARA AK RG 370, BOX 2

Downriver

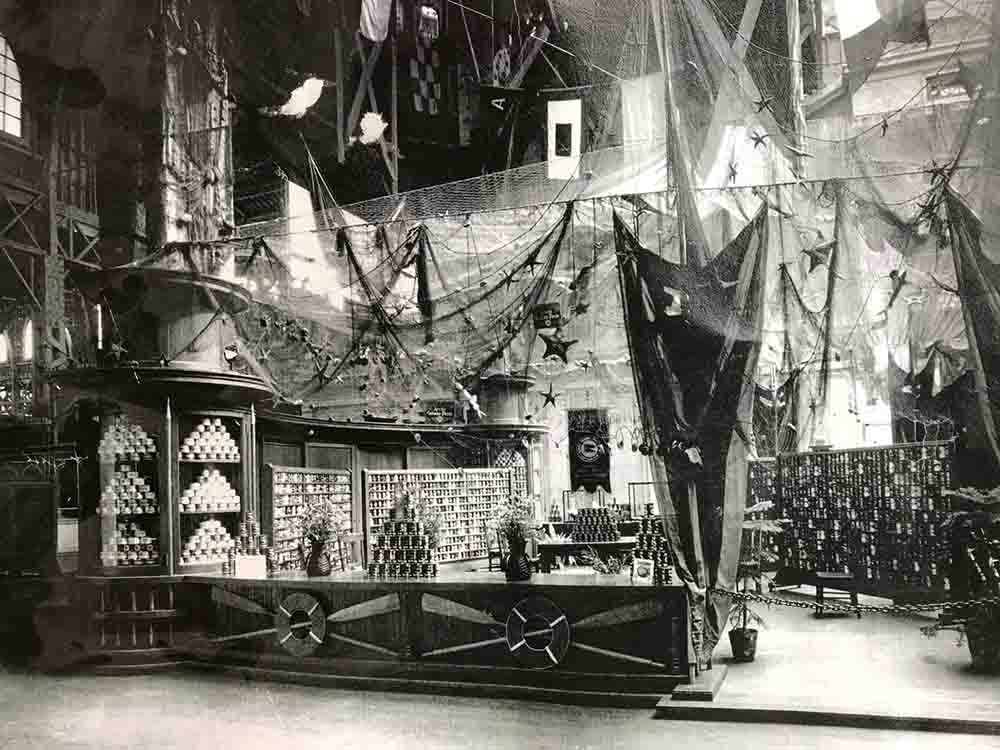

The 130-year-old Diamond NN Cannery is situated on the south bank, near the mouth of the Naknek River, one of five major pristine rivers—Kvichak, Nushagak, Ugashik, Egegik, and Naknek—that drain to Bristol Bay, the eastern-most arm of the Bering Sea. The NN Cannery was part of the broader pattern of commercialized Pacific salmon packing that, before 1937, was the third largest extractive industry in the West, with greater value than gold and copper mining in Alaska (Friday 1994, Gregory and Barnes 1939). The cannery was built by the Del Monte subsidiary, the Alaska Packers Association (APA), which, not only was a corporate juggernaut that dominated Alaska’s fishing industry, but was part of a technological, commercial, and global system that revolutionized the way the world ate (Parkin 2006).

The packing and preparing of salmon for commercial sale transformed the Bristol Bay region. “Of all the agents of change,” writes ethnographer James Vanstone, “none had a greater or more lasting effect…than the commercial fishing industry” (Vanstone 1967: 63). Anthropologist Alan Boraas agrees, noting that salmon canneries, like APA’s Diamond NN Cannery, “represented the Industrial Revolution of the North” (Boraas 1996: 11).

From its establishment as a four-building saltery, to its expansion into a globally reaching, 51-building industrial complex, the NN Cannery was one of the largest, longest running canneries in Alaska. Built in 1890 and processing salmon nearly every summer until 2001, it remains one of the best examples of an intact, twentieth century, Bristol Bay salmon cannery, and constitutes one of the most significant remnants of the canned salmon industry on the West Coast.

Unlike many other Bristol Bay canneries, the NN complex never experienced fire, nor was it ever repurposed for anything other than canning salmon. Contained in its century-old buildings are stories that underpin the historical manifestations of capitalism, incorporation, industrialization, immigration, world wars, global pandemics, statehood, resource management, unionization, segregation, and equal rights.

Importantly, the cannery employed hundreds of residents and thousands of transient workers who produced more canned salmon than any cannery in Alaska. Over time, these cannery workers developed unique identities and stories, which today remain little known or understood.

People from around the world journeyed to South Naknek to can salmon for 120 seasons. Before 1952, APA employed mostly immigrants from Europe to gillnet salmon in double-ender sailboats. These men were from the fishing nations of Italy, Croatia, Norway, and Sweden. Skilled immigrants not only fished but built and maintained both the cannery complex and the salmon boats. The cannery hired Asian crews to process the salmon—first from China, then from Japan, and later, the Philippines—whose distinct cultures and traditions shaped the cannery’s labor landscape and directly linked the Alaskan cannery to the broader Pacific World.

CARVEL ZIMIN, SR, KATMAI PHOTO ARCHIVE, KATMAI NATIONAL PARK AND PRESERVE

TOM CONNELLY

NN CANNERY HISTORY PROJECT

In addition to Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino crews, historically lesser-known Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and Hawaiians also labored at the NN Cannery, representing, in the case of Mexican workers, the largest ethnic group to labor at the cannery before WWII. Erased from historical memory, graffiti etchings on the old bunkhouse walls are some of the scant enduring traces that these people left behind. Indigenous Alaskans also worked at the cannery. Katmai Sugpiaq migrated downriver to South Naknek after the Novarupta volcano destroyed the Savonoski village in 1912 (Dumond 2010). The Spanish Flu pandemic of 1919 drove the survivors to seek cannery work. Despite traditional lifeways lost to cannery work, indigenous residents became major contributors to and caretakers of the operation (APA 1923). Moreover, because the cannery property has never been archeologically investigated, the grounds have the potential to continue the Brooks River archeological story and offer a more complete interpretation of the Naknek River’s cultural past.

The Alaska Packers Association recognized the contributions of its diverse cannery crew. In a 1928 draft report on Alaska’s Salmon Industry, APA President A.K. Tichenor attributed APA’s success to the skilled and dependable cannery people:

The company sends to Alaska each year over 4,000 men and employs in addition, a large number of Eskimos, Indians and other residents of Alaska. 1,000 are Superintendents, Physicians, Bookkeepers, Mechanics, Beachmen, etc. About 1,000 are Fishermen, and the balance consists of other cannery employees. Many nationalities are represented amongst these men, but the Fishermen are usually composed of Italians and Scandinavians. These races [men from fishing nations] seem fitted for this particular branch of the industry.

The more salient features of the Alaska salmon industry are the amount of effort that must be expended in assembling the outfit of material and personnel, their transportation to the fishing grounds, the making of cans, cases, etc. the driving of traps and preparation of fishing gear, upon arrival. The repair of wharves and buildings carried away or damaged by ice and snow during the long winters—so that when the “run” starts the plant may be ready in every particular way.

Owing to the shortness of the canning season, which lasts only about four weeks in Bristol Bay, and the short time which we have for the preparation of the pack, the loading and shipment of salmon in the transporting vessels, before winter sets in, it is essential that the outfit be completed in every respect and that the personnel be composed of men who are dependable and willing workers. (Tichenor 1928: 2).

NN CANNERY HISTORY PROJECT

Despite their knowledge of the operation, machines, and the salmon, cannery workers have existed in the shadows, eclipsed by romantic stories of fishermen—the so-called “Iron Men of Bristol Bay”—and marginalized, exotified, or ignored by writers, curators, even park rangers in the historical narratives of Alaska’s most important salmon fishery. To fully understand the significance of the canned salmon industry and its expansion throughout the West, Alaska and Bristol Bay, historian Donald Worster writes that consideration must be given to “the ethnic histories of the residents, migrants, and immigrants involved in the extraction of the region’s great natural wealth” (Worster 1992). Whether they came from China, Mexico, the Philippines, or simply upriver, the NN Cannery people found dignity through their laborious interactions and forged a deep connection to the surrounding environment. Their diverse traditions left a mark on Naknek history and culture. Their work mattered.

Built originally in 1890 as a saltery by the Arctic Packing Company (APC), the operation was absorbed in 1892 by APA who converted the APC saltery into a salmon cannery in 1894. APA assigned its new asset the initials, NN, likely for NakNek. Using a diamond-shaped accounting symbol around the initials, the cannery was rebranded as the <NN> (pronounced as “Diamond NN” and as shown in the NN Canery Project logo, top) and quickly became the crown jewel of APA’s well-known trademark: “the diamond canneries.”

TRIDENT SEAFOODS

Without a doubt, canneries were and continue to be natural resource extractors—they used technical and organizational skills, engineering knowledge, and energy to transform natural resources—sockeye salmon—into a commodity for world markets. But canneries like APA’s Diamond NN Cannery are also important sites of maritime and labor history that retain the overlooked stories of America’s past.

Trident Seafoods closed the NN Cannery in 2015, opening a rare window for historians to share the collective stories of these “dependable and willing workers.” A grassroots organization sprouted the following year and the NN Cannery History Project began to bring awareness of the history contained in the industrial landscape. Because the NN Cannery has the ability to inform the public about the importance of the salmon, the industry, and its diverse participants, the NN Cannery History Project, with the support of the National Park Service and the Alaska State Historic Preservation Office, is nominating the property as the APA Diamond NN Cannery Maritime Historic District to the National Register of Historic Places. Once designated, the NN Cannery will be the first historic salmon cannery from Bristol Bay to be listed and recognized for its role in interpreting the history of the Naknek River, and its historic ties to the nation and the rest of the Pacific. The cannery’s discarded machines parts, broken boardwalks, skeletal bunkhouses, and graffiti etchings are today’s reminders of Bristol Bay’s forgotten workforce that provide a more comprehensive understanding of the natural, cultural, and economic history of the Naknek River. Like the salmon, cannery people connected the land-based operation to the Pacific waterscape and created an ethnically diverse, economically vital cannery culture. Just as the Brooks River platforms are sites of interpretation of the extraordinary natural history of Katmai, the NN Cannery can interpret the forgotten history of the canned salmon industry, a history built on the foundation of the pristine habitat and unparalleled sockeye salmon runs upriver.

Visit Project Jukebox to hear oral histories from people who worked at the cannery in various capacities, including fish processors, laundry and kitchen workers, machinists, office administrative staff, and superintendents, as well as commercial fisherman and local village residents. These oral histories demonstrate the diversity of cannery workers and honors their contributions as a labor force.

NN CANNERY HISTORY PROJECT

References

Alaska Packers Association (APA). 1923.

Service: The true measurement of any institution lies in the service it renders. APA Collection, Alaska State Archives, Juneau, Alaska.

Birkedal, T. 1993.

Ancient hunters in the Alaskan wilderness: Human predators and their role and effect on wildlife population and the implications for resource management, in Proceedings of the 7th Conference on Research and Resource Management in Parks and Public Lands. Hancock, MI: The George Wright Society.

Boraas, A. 1996.

Turning Point Photo Exhibit. Peninsula Clarion, November 21, 1996.

Dumond, D. E. 2010.

Alaska Peninsula communities displaced by volcanism in 1912. Alaska Journal of Anthropology 8(2): 7-16.

Friday, C. 1994.

Organizing Asian American Labor: The Pacific Coast Canned-Salmon Industry, 1870-1942. Temple University Press.

Gregory, H. E. and K. Barnes. 1939.

North Pacific Fisheries with Special Reference to Alaska. New York.

Moser, J. F. 1902.

Salmon investigations of the steamer Albatross in the summer of 1900. Bulletin of the United States Fish Commission Vol. 21. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Murray, J. 1895.

Report of Special Agent Murray on the salmon fisheries of Alaska. Seal and Salmon Fisheries and Natural Resources of Alaska Vol. II, p.422.

Parkin, K. 2006.

Food Is Love: Advertising and Gender Roles in Modern America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Riggs, Jr., T. 1919.

Annual report for the fiscal year ending June 30. 1919. Governor Territory of Alaska, Office of Governor, Juneau Sept 26, 1919.

Ringsmuth, K. 2013.

At the heart of Katmai: An administrative history of the Brooks River area with special emphasis on bear management in Katmai National Park and Preserve, 1912-2006. Washington, DC: US Department of the Interior.

Tichenor, A. K. 1928.

Value of the canned salmon industry, draft. APA Collection, Center of Pacific Northwest Studies, Bellingham, WA.

Vanstone, J. 1967.

Eskimos of the Nushagak River: An Ethnographic History. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Worster, D. 1992.

Under Western Skies: Nature and History of the American West. Oxford University Press.

Last updated: October 30, 2024