NPS Photo

When a dead whale washes up on a beach in a national park, it is definitely not cause for celebration. On the contrary, there is anguish, worry, and a flurry of activity to investigate, especially if mortality may have been caused by human factors. On the bright side, people are fascinated by whales, thus a stranding provides a rare opportunity for a close look at a wild, ocean-dwelling animal whose body can usually only be glimpsed as it surfaces for air. A dead whale is also a treasure trove of biological information, especially in the case of identified individuals whose life history is known.

In this project, supported by a Coastal Marine Grant administered by the National Park Foundation, we learned that by preparing two spectacular and beautiful whale skeletons for display, it is possible to turn the tragic death of a magnificent animal into an inspiring educational opportunity. This is a story of two whales: an adult female humpback whale known as “Snow” whose Tlingit name is Tsalxaan Tayee Yáay, which translates as “Whale Beneath Mount Fairweather,” and a juvenile female killer whale whose Tlingit name is Keet’k’, meaning “Little Killer Whale.” Read on to learn how these whales, and the people who worked with them, provide an opportunity for people to think about the lives of whales and their ocean ecosystems.

NPS Photo

Whale Beneath Mount Fairweather

Glacier Bay National Park biologist Janet Neilson found the floating body of a humpback whale near the mouth of Glacier Bay on the way home from a whale monitoring survey on July 16, 2001. Park staff secured the carcass and towed it to shore the next day for veterinary examination to determine the cause of death. Dr. Francis Gulland of The Marine Mammal Center Sausalito, California, led a necropsy which revealed a fractured skull and blunt trauma. The trauma was pinpointed to a ship strike that was reported by an observer on July 13, 2001—three days before the body was found. Ship strikes are a real danger for whales and occur fairly often in Alaska (108 documented between 1978 and 2011) most commonly when a whale fails to get out of the path of a fast-traveling vessel.

Southeast Alaska’s humpback whales are baleen whales that feed in rich, high-latitude waters and migrate to wintering grounds in Hawaii for mating and calving. Glacier Bay’s humpback whale monitoring program maintains sighting histories of numerous whales who were first sighted as a calf and return annually to feed, socialize, and raise their young in Glacier Bay and Icy Strait within Glacier Bay National Park.

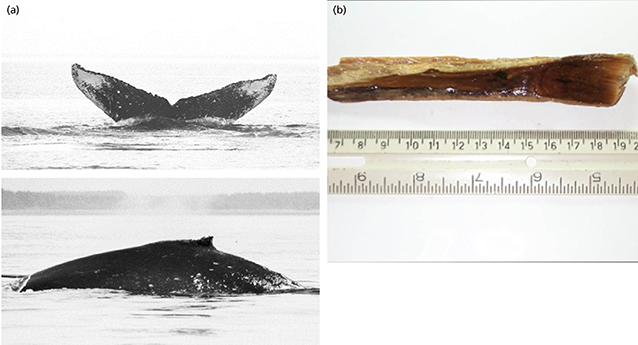

Natural markings on a humpback whale’s (Megaptera novaeangliae) tail and flanks are used to identify individuals (a). The markings on the tail flukes allowed identification of this whale as catalog #68, also known as “Snow.” We know that Snow was a mature female, weighed approximately 70,000 pounds, was 45.5 feet in length, and was pregnant when her body was found. By counting the growth layers in Snow’s ear plug (b), we learned that she was born around 1957. One growth-layer is added per year on these ear plugs and help us understand the lifespan of humpback whales. Typically, humpback whales live to be around 60 years old, but the oldest known whale was 96 years, and Snow was 45 when she died.

Park staff, students, and local volunteers worked together to retrieve the whale skeleton and baleen. Whale bones are notoriously oily: the larger they are, the more oil they contain. The bones were subjected to many cleaning treatments, including soaking in seawater, heating to release oil, pressure-washing, whitening with peroxide, and burial in compost.

The expert crew at Whales and Nails, LLC, led by Dan DenDanto (left with Chris Gabriele, whale biologist and project lead), shipped the entire humpback skeleton to their workshop in Maine, where they finished cleaning the 161 humpback whale bones (weighing over 5,000 pounds), repaired damaged bones, fabricated realistic replicas to replace missing bones, and designed a support system with a graceful posture that brings the whale to life.

Little Killer Whale

A charter vessel reported a dead killer whale on the beach in lower Glacier Bay on August 26, 2005. Park staff responded immediately to assess the situation and retrieve the carcass for veterinary examination. It is believed that the dead killer whale came from AF or AG pod (a resident pod), but it is not known for sure. The little killer whale, Keet’k’, was a juvenile female about 18 months old and still being weaned from nursing. She weighed about 600-800 pounds and was 11.7 feet long

NPS Photo

It was immediately obvious that Keet’k’ had ingested fishing gear, but unknown whether it was the cause of death. A necropsy completed by Dr. Pam Tuomi of the Alaska SeaLife Center revealed a fish hook had pierced the back of her throat; she died of pneumonia and blood poisoning and was also malnourished. Blubber analysis reported high levels of flame retardants, DDT, and other contaminants.

Some toothed whales, including killer whales, have learned to take fish off of commercial or sport fishermens’ lines (known as depredation). Two varieties of fishing gear were found in Keet’k’s body—light, trolling gear and long-line gangion were hanging from her mouth, and a J-hook and circle hook with gangion and snap were found in her stomach.

After cleaning and making a complete inventory of the bones—250 in all and weighing 96 pounds, we hired articulation expert Lee Post (shown at right) to come to Gustavus for two weeks to work with park education specialists, local residents, and students in putting the killer whale skeleton together.

The articulation of Keet’k’ brought a small Alaska town together to work, learn, and play while creating a beautiful exhibit for people to enjoy at the Gustavus Public Library starting in February 2014.

NPS Photo

The story of these whales and the people who worked together to bring their stories to life is even bigger than the bones themselves. Together these unique exhibits provide people with the opportunity to pause and think about the toughness and fragile beauty of a whale’s life and the ocean environment in which they live.

NPS Photo

Education specialists Melissa Senac (left) and Kelly VandenBerg (right), won the National Freeman Tilden Award in 2014 for coordinating Glacier Bay National Park’s efforts to create the humpback and killer whale exhibits and accompanying educational curriculum that brought together kids and adults alike to help prepare and assemble the skeletons.

| Humpback Whale | Killer Whale | |

|---|---|---|

| Date Found | July 16, 2001 | August 26, 2005 |

| Species and Stock | North Pacific humpback whale, (Megaptera novaeangliae) | Killer whale (Orcinus orca) of the Resident ecotype, from AF or AG pod. |

| Length | 45.5 feet | 11.7 feet |

| Age Class | Pregnant sexually mature female. Vertebral growth plates were fused in all bones of the spine, indicating that this whale had reached her full length (physical maturity). | Juvenile female killer whale, age believed to be about 18 months old (based on her length) and growth layers in tooth. Milk was found in the stomach, indicating that she was partially weaned (a calf may nurse for 12 months and is typically weaned at 1-2 yrs.) |

| Est. Weight | About 70,000 lbs. | 600 – 800 lbs. (~300-400 lbs. at birth) |

| Skeleton Weight | 3,718 lbs | 70 lbs |

| Skull Weight Including Jaws | 1,322 lbs | 26 lbs |

| Number of Bones | 161 bones | 250 bones (including all epiphyseal plates/growth plates) |

| Feeding Apparatus | over 700 baleen plates | 48 teeth |

| Cause of Death | Necropsy led by Dr. Frances Gulland. DVM of The Marine Mammal Center revealed a fractured skull and blunt trauma caused by a ship strike that had been reported by an observer on July 13, 2001. | Necropsy led by by Dr.Pam Tuomi, DVM of the Alaska Sea Life Center revealed a fish hook had pierced the back of her throat (oropharynx). She died of pneumonia and septi-cemia (blood poisoning) with underlying malnutrition. |

| Biological Findings | Counts of growth-layers in her earplug revealed that Snow was born around 1957. which helped resolve a long-standing controversy about the lifespan of humpback whales. | Blubber analysis reported high levels of flame retardants (PBDE’s), DDT and other contaminants. |

| Conservation Issue | Ship strikes are becoming increasingly common | Some toothed whale species have learned to take fish off of commercial or sport fishermens' lines (known as depredation) to make a living. Two varieties of fishing gear were found in this whale's body: light trolling gear and long-line gangion were hanging from her mouth, and a J-hook and a circle hook with gangion and snap was found in her stomach. |

| Skeleton Articulation Expert | Dan DenDanto, Whales & Nails LLC, Seal Cove, Maine | Lee Post, The Boneman, Homer, Alaska |

| Exhibit Grand Opening Date | June 25, 2014 | February 25, 2014 |

| Hidden Facts About the Display | Several bones were missing when NPS collected the skeleton 15 months after the whale was towed ashore. Therefore, some bone replicas were fabricated by Whales and Nails, and two cervical vertebrae and the final 3 vertebrae were borrowed from other humpback whales that stranded in Southeast Alaska in later years. | The 48 teeth on display are cast replicas of the real teeth, which have been preserved for educational use. |

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 15 Issue 1: Coastal Research Science in Alaska's National Parks.

Last updated: December 5, 2016