War has always found its focus where roads converge. Like so many of the significant points of conflict marking the quarrel between North and South, Manassas, Virginia was the center of a network of transportation and commerce. Here, vital arteries of communication and logistics came together and connected.

Threatened by the overwhelming approach of the 35,000 troops of the Union Army of Northeastern Virginia, the Confederate army was put to work defending the vital junction of railroads at Manassas.

New York Times

At Manassas Junction, the iron rails of the Orange & Alexandria and Manassas Gap railroads joined near the banks of Bull Run, a mere 27 miles from Washington, while the macadam pavement of the Warrenton Turnpike traversed the pastoral fields and woods that soon became a battlefield.

These routes of transportation and communication were rooted in the agricultural economy of Virginia: the turnpike was constructed to transport grain harvests by wagon from the Shenandoah Valley to the markets of Alexandria. The railroads supplanted the turnpike with steam locomotive transportation. The Shenandoah became the "breadbasket of the Confederacy," helping feed Richmond, the political and industrial capital of the Confederacy.

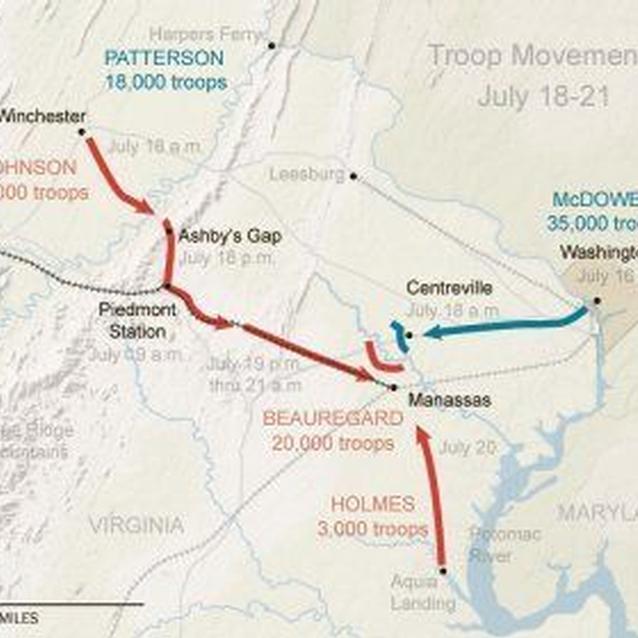

As the war began, existing arteries of communication were transformed for use in logistical communications: the transport of troops and military materiel to sustain armies on campaign. Threatened by the overwhelming approach of the 35,000 troops of the Union Army of Northeastern Virginia, the Confederate army was put to work defending the vital junction of railroads at Manassas.

At the First Battle of Manassas, the Manassas Gap Railroad transported 12,000 troops of the Confederate Army of the Shenandoah to bolster General P.G.T. Beauregard's beleaguered Confederate forces. In one of the first uses of rails to move armies to battle, the Confederate infusion of reinforcements arrived just in time to stem the Union tide. The crushed Union army retreated, moving quickly back along the turnpike's deteriorated macadam to Washington.

Library of Congress

Thirteen months later, the iron rails and tarred gravel brought contending armies to the same pastures and woodlots near Bull Run. The Confederates had abandoned Manassas Junction in the spring of 1862 and by August the area had become a major Union supply depot. Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson captured and pillaged the depot, burning the stockpile after his hungry troops feasted on Union delicacies including tinned tongue and lobster.

Jackson's wing of the Confederate army then withdrew to Stony Ridge behind an unfinished railroad grade to await the Union army's approach. The cuts and fills of this unfinished railroad became an almost impregnable fortification for Jackson's troops in the ensuing battle, as Maj. Gen. John Pope strove to dislodge the Confederates with piecemeal assaults upon the embankment.

Beyond Manassas, national economies were harnessed for a protracted struggle to restore the Union or establish Confederate independence. The economic bounty of American agriculture and industry became the target of war. Pope issued harsh orders to his troops prior to the Second Manassas campaign to destroy whatever economic resources of the enemy they could not take away. An assault upon the Confederate economy and upon the populace supporting the Confederacy was implicit in Pope's orders to his troops. Seizure of civilian property as "contraband of war," formerly a punishable act, was encouraged.

The Second Manassas campaign introduced the first stirrings of this new type of warfare, waged upon the economic sustainability of the enemy, under the assumption that a blow struck against the ability of the "secessionists" to support their armies in the field was a legitimate act of war. Whereas the First Battle of Manassas witnessed armies at war, the Second Battle expanded on that concept as civilian populations became embroiled in the struggle.

Despite the revolutionary conduct of Pope's campaign, the Union was again defeated; his army retreated with Pope disgraced. But this new type of economic warfare would persist and eventually become the norm, with harsh consequences for the Confederates during the campaigns of Union generals Sherman and Sheridan in 1864 and 1865.

Last updated: February 4, 2015