Last updated: November 16, 2023

Article

The American Home Front Before World War II: World War I, The Great Depression, and The New Deal

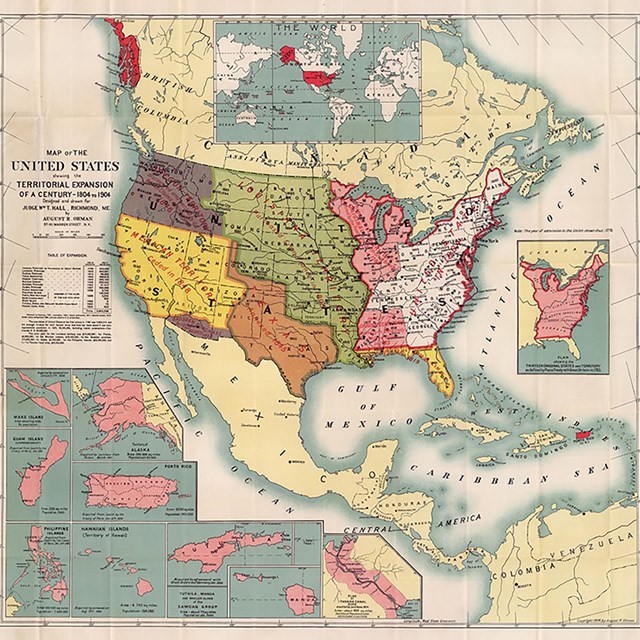

Wikimedia.

To meet the demand, American industries expanded their production. Unemployment dropped, and money flowed into the pockets of many Americans. [3] Black Americans moving from the agricultural South to Northern industrial cities filled the growing demands for labor. This was the First Great Migration. As well as the promise of good paying jobs, African Americans left the South to escape Jim Crow segregation. Although better, things were still hard in the North. [4] The frequency and intensity of racial violence against African Americans increased during World War I. This included thousands of lynchings and the founding and rise in power of the revived Ku Klux Klan. In 1917 alone, deadly race riots erupted in East St. Louis, Illinois and in Houston, Texas. Rarely were the white perpetrators punished. [5]

Collection of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum (MO 1969.51).

World War I

The US remained neutral until April 6, 1917 when Congress declared war on Germany. [6] Just as they would 25 years later in World War II, civilian industry shifted to military production. Elsewhere on the home front, children collected scrap and people planted War Gardens. In the fall, gardeners canned and otherwise preserved their produce. Many people voluntarily limited their meat consumption. And the federal government sold Liberty Bonds and Thrift Stamps to raise money. Twenty-four million men registered for the draft and almost 2.1 million Americans went to war either in the uniformed service or as spies. [7]Households with members serving in the military hung service flags in their windows. Each blue star represented someone serving; a gold star replaced the blue for each of those lost in the war. These service flags became popular again in World War II, and their use continues. [8] In the media, the federal government’s Committee on Public Information “advertised” the war. They promoted support via patriotic posters, records, silent films, sheet music, and newspaper articles. There were also people who opposed the war, including thousands who declared themselves conscientious objectors. The government cracked down on dissenters, arresting them and looking the other way when they were murdered. Some conscientious objectors worked in noncombatant roles; others worked on farms. Several went to prison or were forced into conscientious objector camps. [9]

Like in World War II, Americans on the home front faced the threat of direct enemy attack. Focused on the war in Europe and underestimating German technology, the United States was caught off guard when four German Unterseeboots (U-Boats) began sinking American ships along the East Coast. Between April 1917 and November 1918, the U-Boats sank 200 merchant and naval vessels. U-Boats also hit land targets, including shelling Nauset Beach on Cape Cod, Massachusetts and a gas attack of a coast guard station at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, North Carolina. Only minor injuries were reported.[10] Elsewhere, German agents bombed the US Capitol; blew up a munitions depot in New Jersey; worked to incite a war between the US and Mexico; and used germ warfare by infecting horses and mules heading to the front lines with anthrax and other diseases.[11]

Originally published in The Chicago Defender, September 4, 1920.

By the end of World War I on November 11, 1918, almost 117,000 Americans had died and another 204,000 wounded. Many more came home with shell shock and other war-related psychological and neurological conditions, including what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD. [14] While the official American casualty count was much lower than in other countries, the impact on the American people was significant. [15]

Black soldiers returning home expected social change. They had served their country, many giving the ultimate sacrifice. They anticipated that they had earned the respect of the government and their fellow citizens. They did not get the welcome home they had hoped for. Quite the opposite. Many white citizens worked to keep society segregated, and to keep African Americans in second-class status. Anti-Black violence and lynching increased so much that the summer of 1919 became known as the Red Summer. [16]

Wireless Age August 1923, p. 26.

Optimistic about the future and with money in their pockets, Americans spent money. A lot of money. They bought products they had gone without during the war and the new products that were available because of the war. Automobiles hit a growing road network in record numbers, and restaurants and gas stations popped up to serve travelers. Those able to drive to work in the cities moved to the new suburbs springing up across the country. Hollywood became the center of the global film industry, and radios carried jazz, news, and other entertainment into Americans’ living rooms. In Harlem and other places where African Americans had moved during the war, Black arts, communities, and thought flowered. The unregulated stock market soared, increasing to six times its value between 1921 and 1929, enticing people to invest. Historians refer to this period as the “Roaring 20s.” In the media, this era is represented by iconic flapper fashion, speakeasies, and rum-runners. It was also the peak era of the Ku Klux Klan, who, with up to five million members, operated openly across the country. Black communities and those of non-white and non-Protestant Americans were targets of violence – including the Tulsa Massacre.[19]

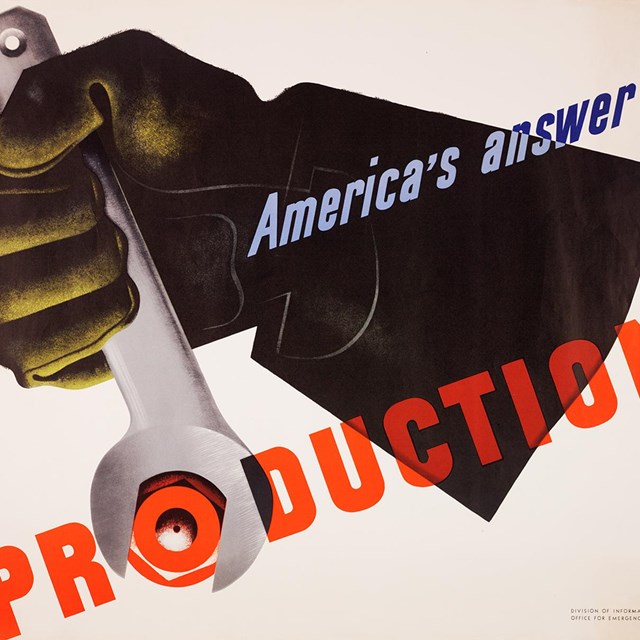

Collection National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 195524).

The Great Depression

The Roaring 20s did not last. In late October 1929, the US stock market crashed, wiping out billions of dollars of Americans’ wealth and investment. With international economies already unstable, the crash plunged the United States and other countries into crisis. In the US, we know it as the Great Depression. By June of 1933, American stocks had lost as much as 89% of their value. The impact extended to financial institutions, and by the same time, almost a third of US banks (about 7,000 of them) had failed. The American spending (and investing) spree of the Roaring 20s was over. [20]Despite federal attempts to right it, the economy continued to worsen. By 1933, in the face of increasing numbers of business failures, unemployment in the US reached almost 25%. Worker wages and business profits were also down. [21]

At the same time, a serious drought known as the Dust Bowl hit the continental US beginning in 1930. It devastated agriculture particularly in the Midwest. [22] Unable to find work and with farms buried under dust, farmers, businesses, and families defaulted on loans. Hundreds of thousands of Americans became homeless, and millions of people moved around the country looking for relief. Many lived in shantytowns built of cardboard and abandoned cars called “Hoovervilles” (President Hoover was in office at the time). Others hitched rides on trains and crisscrossed the country looking for work. In Washington DC, thousands of veterans of World War I gathered, demanding payment of a promised bonus for serving. In cities, people begged for food on the streets and went to soup kitchens, often waiting in long breadlines. Malnutrition spread, particularly among children, and many families separated to try to survive. Americans felt helpless, and had little confidence in the future. [23] President Hoover tried to fix the economy, but it continued to worsen. Hoover lost the election in 1932 to Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR).

Collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum (1965.18.35).

FDR and the New Deal

FDR won the 1932 presidential election – his first of an unprecedented four. He campaigned on the promise of a New Deal that would transform America, bringing relief from the devastation of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. He took office on March 4, 1933 and in his first inaugural address, acknowledged the challenges facing the country, and pledged honesty and candor with the American public.[24] One way he did this was over the radio. His conversational Fireside Chats let the President speak directly to the public, bypassing the press. Radio broadcasters carried his first Fireside Chat into American homes just a few days after he took office. [25]Under President Roosevelt’s administration, the federal government poured money into the economy, passed laws, and developed programs to pull the nation out of the Depression. Together, these reforms make up the New Deal. They actively shaped America in the years leading up to and into World War II. Many of them continue today, including a federal minimum wage, the right to unionize, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Social Security, unemployment insurance, overtime pay, and supplemental food programs (SNAP, food stamps). [26]

New Deal programs were largely successful in righting the American economy and improving the situations of all Americans – though white Americans benefitted more than Black Americans and other Americans of color.[27] Programs like the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the Public Works Administration (PWA), and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) provided over 10 million jobs and transformed America. Participants built hundreds of thousands of miles of roads and bridges and installed thousands of miles of water systems and electrical grids. [28] These improved life for Americans in general, but also boosted national security. By 1936, the economy was pretty much back to where it had been in the late 1920s. Millions of Americans were working, and unemployment had dropped from 25% to 11%. Despite an economic downturn fueled by the government cutting spending and increasing taxes in 1937, by 1938, the economy was pretty much on solid footing. [29]

World War II was not the only reason that the Great Depression ended. But the War did speed recovery as Americans found work and businesses found profits in supplying the Allies (and later the US military) with food and weapons. It also led to the end of many New Deal programs as participants found wartime jobs and entered military service. [30]

This article was written by Megan E. Springate, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, for the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

[2] Myre 2017; Ryan 2020. Several Ford plants established before World War I are listed on the National Register of Historic Places or designated National Historic Landmarks. Several have also been documented by the Historic American Engineering Record.

Built: 1904

-- The Ford Piquette Avenue Plant in Detroit, Michigan was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on February 22, 2002 and designated a National Historic Landmark on February 17, 2006. It has been documented by the Historic American Engineering Record.

Built: 1909

-- The Ford Service Building in Detroit, Michigan has been documented by the Historic American Engineering Record.

Built: 1910

-- The Highland Park Ford Plant in Michigan was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on February 6, 1973 and designated a National Historic Landmark on June 2, 1978.

Built: 1913

-- The Ford Cambridge Assembly plant in Cambridge, Massachusetts has been documented by the Historic American Engineering Record.

Built: 1914

-- The Ford Motor Company – Columbus Assembly Plant in Ohio was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on March 15, 2021.

-- The Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant in Atlanta, Georgia was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 10, 1984.

Built: 1915

-- The Cleveland Branch Assembly Plant in Ohio was documented by the Historic American Engineering Record.

-- The Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on November 20, 2018.

-- The Ford Motor Company Cincinnati Plant in Ohio was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 25, 1989.

-- The Oklahoma City Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 10, 2014.

-- TheOmaha Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant in Nebraska was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 29, 2004.

Built: 1916

-- The Ford Motor Company Building in Washington, DC was documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

[3] Byerly 2010: 83; Morrow 2019: 107; Rockoff 2004: 4, 7.

[4] Morrow 2019: 107-109; National Museum of African American History and Culture n.d. b.

[5] Cooper 2019: 105; Morrow 2019: 99, 115; Odlum 2018; Winter 2019: 27.

[6] For nuanced discussions about why the United States entered World War I, see Capozzola et al. 2015: 471-479 and Winter 2019: 23-26.

[7] Byerly 2010: 85; Capozzola et al. 2015: 495; Rockoff 2004: 19; United States World War One Centennial Commission 2021. For a discussion of American archaeologists who acted as spies on behalf of the United States, see Browman 2011. As an example of the volunteer effort, over 60,000 women volunteered to place over 4.5 million Liberty Loan reminder cards in library books across the US. Efforts like this paid off: at the end of World War I, more than $17 billion had been raised for the war effort (Oberg n.d.).

[8] United States World War One Centennial Commission 2021; Remley 2019: 113.

[9] Delaware Historical & Cultural Affairs n.d.; Yoder 2020; Winter 2019: 27.

[10] MacLean 2018.

[11] Blum 2014; Cavanaugh 2018; Daily Capital Journal 1916; Federal Bureau of Investigations n.d.; Jones 2015, 2017; Washington Post 1918. These events were catalysts to passing the Espionage Act.

[12] The islands north of the equator went to Japan; the islands south of the equator were placed under Australian administration as the Territory of New Guinea.

[13] Williams 1933: 428. The Panama Canal Zone and the US Virgin Islands both became part of the Greater United States just prior to World War I.

[14] Capozzola et al. 2015: 483-484.

[15] Rockoff 2004: 19.

[16] Bunch 2019a: 12; National Archives and Records Administration 2021; Reft 2017. See also “Returning Soldiers” by W.E.B. Dubois published in 1919, volume 18 of The Crisis. Recognition came slowly. For example, Sgt. Henry Johnson and his men served in France under French command, since the US military was segregated. Sgt. Johnson saved the lives of his men while under attack and was awarded the Croix de Guerre avec Plume by the French government. It was not until well after his death that the US government granted him the Medal of Honor. In 2023, the US Army renamed Fort Polk, Louisiana to Fort Johnson (National Park Service 2023b; Treisman 2023).

[17] Bunch 2019b: 140; Myre 2017.

[18] Capozzola et al. 2015: 483, 493-494; United States Department of State n.d.

[19] Bryant 1998a; Bunch 2019b: 140; Capozzola et al. 2015: 495; National Museum of African American History and Culture n.d. a; Odlum 2018; Richardson et al. 2013; Rothman 2016; Weeks 2015

[20] The larger causes of the global depression remain a point of discussion and contention among economists. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis n.d.a, n.d.b; Richardson et al. 2013; Social Welfare History Project 2011.

[21] Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum n.d.

[22] McLeman et al. 2014: 418-422; National Archives and Records Administration n.d.; National Weather Service, n.d.; Public Broadcasting Service 2022a, 2022b, 2022c. This massive migration of people within the United States is rivaled only by the Great Migration of African Americans out of the South between 1910 and 1970 (approximately 2 million between 1910 and 1940, and another 3 million within 20 years of the end of World War II).

[23] Bryant 1998b; Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum n.d. The protesters in DC, known as “The Bonus Army,” numbered somewhere between 10,000 and 20,000. After months of protest, on July 28, 1932, the President (Herbert Hoover) sent in Army and police forces to disperse them. General Douglas MacArthur (who later led US forces in the Pacific during World War II) led the military forces. Several protesters were injured and at least one killed. The veterans finally received their bonuses in 1936 (National Park Service 2023a).

[24] Roosevelt 1933. This was also the speech where he said, “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself – nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.”

[25] They were not originally called Fireside Chats; but that is how they were introduced, and it stuck. FDR gave 30 Fireside Chats between March 12, 1933 and June 12, 1944. You can read them online via the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. Biser 2016; Brechin 2014.

[26] You can explore the impact of the New Deal across the country and by program at The Living New Deal, a project of the Department of Geography at the University of California Berkeley.

[27] Several New Deal policies negatively impacted African Americans, Native Americans, and other people of color at the time, and set the stage for generational impacts that resonate even until today. For example, the National Labor Relations Act excluded agricultural and domestic workers (largely Black and Latino) from its protections. This kept these workers unable to organize, and living and working in exploitive, precarious, and often abusive situations. The building of dams on the Columbia River flooded Native hunting grounds and blocked traditional salmon runs – all without even providing access to water for irrigating tribal lands. The Federal Housing Administration codified redlining by refusing to insure mortgages in and around Black neighborhoods, while subsidizing developers building subdivisions and neighborhoods for white Americans – and requiring that they not sell to African Americans. Redlining was also used to keep Jewish people out of white neighborhoods. As well as preventing the creation of intergenerational wealth, there continue to be environmental repercussions, including persistent heat islands that continue to affect communities of color (Anderson 2020; Bird 2022; Faber and Sucsy 2021; Gross 2017; Living New Deal n.d.; United States Environmental Protection Agency 2022). For a nuanced discussion of race and the New Deal, see Living New Deal n.d.

[28] Ermentrout 1982: 99; Goodfellow et al. 2009: 19, 28-29; Kennedy 1999: 252-254; Public Broadcasting Service 2022d; Thompson 2016a, 2016b. WPA workers also made 382 million pieces of clothing and prepared and served 1.2 billion school lunches. Film exists of CCC work being done. For example, this video shows CCC work in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. This one shows anAfrican American CCC team working in New Jersey state parks.

[29] Kennedy 1999: 350, 354-355.

[30] da Cruz 2018; Goodfellow et al. 2009: 15, 31, Appendix C; Thompson 2016a, 2016b. They also were involved in the construction of Hunter College in the Bronx, which was taken over by the Navy in World War II and used as a training facility.

[31] Glanton 2020.

[32] Parshina-Kottas et al. 2021.

[33] Mahoney 2012; Thompson 2017.

Bird, Marlee (2022) “The Temperature of Disinvestment: Examining Urban Heat Islands and Historically Redlined Communities.” National Community Reinvestment Coalition, July 7, 2022.

Biser, Margaret (2016) “The Fireside Chats: Roosevelt’s Radio Talks.” The White House Historical Association, August 19, 2016.

Blum, Howard (2014) “Author Interviews: During World War I, Germany Unleashed ‘Terrorist Cell In America.’” Fresh Air (National Public Radio), February 25, 2014.

Brechin, Gray (2014) “The First Family of Radio: Voices of Destiny, The Roosevelts on the Radio.” The Living New Deal, December 24, 2014.

Browman, David L. (2011) “Spying by American Archaeologists in World War I.” Bulletin of the History of Archaeology 21(2): 10-17.

Bryant, Joyce (1998a) “The Great Depression and New Deal.” Curricular Resources: American Political Thought Volume IV, Unit 4, Section 2.

--- (1998b) “The Great Depression and New Deal.” Curricular Resources: American Political Thought Volume IV, Unit 4, Section 3.

Bunch, Lonnie G., III (2019a) “Introduction.” In Kinshasha Holman Conwill (ed.), We Return Fighting: World War I and the Shaping of Modern Black Identity, pp. 9-12. Smithsonian Books, Washington, D.C.

--- (2019b) “Epilogue: On the Horizon – Toward Civil Rights.” In Kinshasha Holman Conwill (ed.), We Return Fighting: World War I and the Shaping of Modern Black Identity, pp. 137-140. Smithsonian Books, Washington, D.C.

Byerly, Carol R. (2010) “The U.S. Military and the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919.” Public Health Reports, 125(Supplement 3): 82-91.

Capozzola, Chris, Andrew Huebner, Julia Irwin, Jennifer D. Keene, Ross Kennedy, Michael Neiberg, Stephen R. Ortiz, Chad Williams, and Jay Winter (2015) “Interchange: World War I.” The Journal of American History 102(2): 463-499.

Cavanaugh, Ray (2018) “The Surprising Story of World War I’s Only Attack on US Soil.” Time, July 20, 2018.

Cooper, Brittney (2019) “Mary Church Terrell and Ida B. Wells.” In Kinshasha Holman Conwill (ed.), We Return Fighting: World War I and the Shaping of Modern Black Identity, pp. 102-105. Smithsonian Books, Washington, D.C.

Daily Capital Journal (1916) “Munitions Explosion Was Felt in Five States.” Daily Capital Journal (Salem, Oregon), July 31, 1916, p. 1.

da Cruz, Frank (2018) “New Deal National Defense Projects in New York City 1933-1943.” New York City New Deal, December 7, 2018.

Delaware Historical & Cultural Affairs (n.d.) “The U.S. During World War I.” Delaware Historical & Cultural Affairs,

Ermentrout, Robert Allen (1982) Forgotten Men: The Civilian Conservation Corps. Exposition Press, Smithtown, NY.

Faber, Jacob and Anna Sucsy (2021) “Impact of Government Programs Adopted During the New Deal on Residential Segregation Today.” Fast Focus Research / Policy Brief No. 51-2021. Institute for Research on Poverty, February 2021.

Federal Bureau of Investigation (n.d.) “Black Tom 1916 Bombing.” Famous Cases & Criminals.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (n.d.a) “How Bad Was the Great Depression? Gauging the Economic Impact.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

--- (n.d.b) “What Caused the Great Depression?” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis,

Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum (n.d.) “What was the Great Depression?” Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

Glanton, Dahleen (2020) “Returning South: A Family Revisits A Double Lynching That Forced Them To Flee to Chicago 100 Years Ago.” Chicago Tribune, July 13, 2020.

Goodfellow, Susan, Marjorie Nowick, Chad Blackwell, Dan Hart, Kathryn Plimpton (2009) “Nationwide Context, Inventory, and Heritage Assessment of Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps Resources on Department of Defense Installations.” Department of Defense Legacy Resource Management Program, Project Number 07-357, July 2009.

Gross, Terry (2017) “A ‘Forgotten History’ of How the US Government Segregated America.” Fresh Air, National Public Radio, May 3, 2017.

Jones, Mark (2017) “’Tony’s Lab’ and World War I Germ Sabotage in Washington.” Boundary Stones: WETA’s History Website, April 5, 1017.

--- (2015) “Terrorism Hits Home in 1915: US Capitol Bombing.” Boundary Stones: WETA’s History Website, June 22, 2016.

Kennedy, David M. (1999) Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945. Oxford University Press, New York.

Library of Congress (n.d.) “Primary Source Set: The Industrial Revolution in the United States.” Classroom Materials, Library of Congress.

Lind, Michael (2013) Land of Promise: An Economic History of the United States. Harper, New York.

Living New Deal (n.d.) “The New Deal and Race.” The Living New Deal. https://livingnewdeal.org/new-deal-and-race/

Lyons, Jeffrey K. (2005) “The Pacific Cable, Hawai’i, and Global Communication.” The Hawaiian Journal of History 39: 35-52.

MacLean, Casey (2018) “World War I on the Homefront.” National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, May 2018.

Mahoney, Eleanor (2012) “Public Works of Art Project in Washington State.” The Great Depression in Washington State, Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium, University of Washington.

McLeman, Robert A., Juliette Dupre, Lea Berrang Ford, James Ford, Konrad Gajewski, and Gregory Marchildon (2014) “What We Learned from the Dust Bowl: Lessons in Science, Policy, and Adaptation.” Population and Environment 35: 417-440.

Mokyr, Joel (1998) “The Second Industrial Revolution, 1870-1914.” Manuscript, Northwestern University, August 1998.

Morrow, John H., Jr. (2019) “At Home and Abroad: During and After the War.” In Kinshasha Holman Conwill (ed.), We Return Fighting: World War I and the Shaping of Modern Black Identity, pp. 97-130. Smithsonian Books, Washington, D.C.

Myre, Greg (2017) “From Wristwatches to Radio, How World War I Ushered In The Modern World.” Weekend Edition Sunday, National Public Radio, April 2, 2017.

National Archives and Records Administration (2021) “Racial Violence and the Red Summer.” National Archives and Records Administration, African American Heritage, June 28. 2021.

--- (n.d.) “The Great Migration (1910-1970).” National Archives and Records Administration, African American Heritage.

National Museum of African American History & Culture (n.d.a) “A New African American Identity: The Harlem Renaissance.” National Museum of African American History & Culture.

--- (n.d.b) “Double Victory: The African American Military Experience.” National Museum of African American History & Culture.

National Park Service (2023) “The 1932 Bonus Army.“ National Park Service, July 25, 2023.

--- (2023b) “Henry Johnson (1892-1929).” National Park Service, July 17, 2023.

National Weather Service (n.d.) “The Black Sunday Dust Storm of April 14, 1935.” National Weather Service.

Oberg, Lisa (n.d.) “Homefront.” Washington on the Western Front: At Home and Over There.

Odlum, Lakisha (2018) “Second Ku Klux Klan and The Birth of a Nation.” Primary Source Sets, Digital Public Library of America.

Parshina-Kottas, Yuliya, Anjali Singhvi, Audra D.S. Burch, Troy Griggs, Mika Gröndahl, Lingdong Huang, Tim Wallace, Jeremy White, and Josh Williams (2021) “What the Tulsa Race Massacre Destroyed.” New York Times, May 24, 2021.

Public Broadcasting Service (2022a) “The Drought.” American Experience, Surviving the Dust Bowl.

--- (2022b) “Mass Exodus From the Plains.” American Experience, Surviving the Dust Bowl.

--- (2022c) “Timeline: The Dust Bowl.” American Experience, Surviving the Dust Bowl.

--- (2022d) “The Works Progress Administration.” American Experience: Surviving the Dust Bowl.

Reft, Ryan (2017) “World War I: Immigrants Make a Difference on the Front Lines and at Home.” Library of Congress Blog, September 26, 2017.

Remley, Douglas (2019) “Flag of Service.” In Kinshasha Holman Conwill (ed.), We Return Fighting: World War I and the Shaping of Modern Black Identity, pp. 113. Smithsonian Books, Washington, D.C.

Richardson, Gary, Alejandro Komai, Michael Gou, and Daniel Park (2013) “Stock Market Crash of 1929.” Federal Reserve History, November 22, 2013.

Rockoff, Hugh (2004) “Until it’s Over, Over There: The U.S. Economy in World War I.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, Working Paper 10580.

Roosevelt, Franklin D. (1933) “First Inaugural Address of Franklin D. Roosevelt. March 4, 1933.” The Avalon Project.

Rothman, Joshua D. (2016) “When Bigotry Paraded Through the Streets.” The Atlantic, December 4, 2016.

Ryan, Mick (2020) “Radio, Airplanes, and World Wars: Next Steps for the Profession of Arms.” Modern War Institute at West Point, December 15, 2020.

Social Welfare History Project (2011) “Stock Market Crash of October 1929.” Social Welfare History Project.

Thompson, Lisa (2017) “Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) (1933).” The Living New Deal, March 3, 2017.

--- (2016a) “Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) (1933).” The Living New Deal, November 18, 2016.

--- (2016b) “Works Progress Administration (WPA) (1935).” The Living New Deal, November 18, 2016.

Treisman, Rachel (2023) “The US Army Renames a Base in Honor of Sgt. William Henry Johnson, a Black WWI Hero.” National Public Radio: History, June 14, 2023.

United States Department of State (n.d.) “The Neutrality Acts, 1930s.” Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations, Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute, United States Department of State.

United States Environmental Protection Agency (2022) “Heat Islands and Equity.” United States Environmental Protection Agency, December 12, 2022.

United States World War One Centennial Commission (2021) “The Homefront.” United States World War One Centennial Commission.

Washington Post (1918) “Victims Gassed by U-Boat Reported Out of Danger; Brood of Chickens Killed.” Washington Post, August 13, 1918, p. 1.

Weeks, Linton (2015) “When The KKK Was Mainstream.” NPR History Dept., March 19, 2015.

Williams, E.T. (1933) “Japan’s Mandate in the Pacific.” The American Journal of International Law 27(3): 428-439.

Winter, Jay (2019) “A Global War.” In Kinshasha Holman Conwill (ed.), We Return Fighting: World War I and the Shaping of Modern Black Identity, pp. 17-39. Smithsonian Books, Washington, D.C.

Yoder, Anne M. (2020) “Database of Names & Other Information.” World War I Conscientious Objector Database, March 9, 2020.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The American Home Front Before World War II

3. The American Home Front and the Buildup to World War II

3B The Selective Service Act and the Arsenal of Democracy

4. The American Home Front During World War II

4A A Date That Will Live in Infamy

4A(i) Maria Ylagan Orosa

4C Incarceration and Martial Law

4D Rationing, Recycling, and Victory Gardens

4D(i) Restrictions and Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii) Food Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(a) Nutrition on the Home Front in World War II

4D(ii)(b) Coffee Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(c) Meat Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(d) Sugar: The First and Last Food Rationed on the World War II Home Front

4D(iii) Rationing of Non-Food Items on the World War II Home Front

4D(iv) Home Front Illicit Trade and Black Markets in World War II

4D(v) Material Drives on the World War II Home Front

4D(v)(a) Uncle Sam Needs to Borrow Your… Dog?

4D(vi) Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front

4D(vi)(a) Canning and Food Preservation on the World War II Home Front

4E The Economy

4E(i) Currency on the World War II Home Front

4E(ii) The Servel Company in World War II & the History of Refrigeration

5. The American Home Front After World War II

5A The End of the War and Its Legacies

5A(i) Post World War II Food

More From This Series

-

The Home Front Before World War IIThe Greater United States

The Home Front Before World War IIThe Greater United StatesTo understand the geography of the American home front in World War II, we need to go back as far as the middle of the 1800s.

-

Home Front Buildup to World War IIThe Draft and the Arsenal of Democracy

Home Front Buildup to World War IIThe Draft and the Arsenal of DemocracyWorld War II began on Sept. 1, 1939. In the US, the government implemented a peacetime draft and expanded manufacturing.

-

Home Front Buildup to World War IIPlan for the Worst, Hope for the Best

Home Front Buildup to World War IIPlan for the Worst, Hope for the BestAmericans knew of the growing conflict during the 1930s. While trying to stay out of it, the government was also quietly preparing for war.

Tags

- world war i

- world war ii

- world war ii home front

- wwii

- home front

- homefront

- economic history

- industrial history

- transportation history

- history of communications

- labor history

- great migration

- african american history

- jim crow

- military history

- spies

- massachusetts

- michigan

- georgia

- north carolina

- ohio

- pennsylvania

- oklahoma

- nebraska

- washington dc

- new jersey

- louisiana

- us in the world community

- international relations

- northern mariana islands

- palau

- marshall islands

- league of nations

- japan

- germany

- entertainment history

- harlem renaissance

- new york

- roaring 20s

- tulsa massacre

- great depression

- dust bowl

- bonus army

- presidential history

- president hoover

- president roosevelt

- new deal

- ccc

- wpa