Last updated: November 24, 2023

Article

When Communities Lead the Way

Community (led) science takes scientific research outside park boundaries and into people’s lives. The effects can be transformational.

By Tim Watkins, Claudia Santiago, Ashley Pipkin, and Abe Miller-Rushing

Image credit: NPS / Claudia Santiago

“Shlork, shlork, shlork.” The mud made a squelching noise as it tried to pull off the geologist’s rubber boots. It bunched their socks around their toes as they walked across the waterlogged floodplain.

But despite the discomfort, they and their graduate students pushed on toward the study plot, GPS units in hand and backpacks laden with coring equipment. They had to collect sediment samples right after the most recent flood if they were to successfully test their ideas about storm frequency and sedimentation. They were also eager to meet the park’s field technicians, waiting up ahead, who they would train. This national park had agreed that increased flooding was an important problem to study, and the team was glad. Because that would lead to more collaboration between the park and the university, more thesis projects for students, and more articles published in scientific journals.

This is a hypothetical scene, but it has elements common to most park science projects: scientists, some equipment, a hypothesis or problem to test, data to be collected, an institution, and a report. But what about the person who asks the question or identifies the problem in the first place? Is that always a degree-holding scientist or a government agency? Not necessarily.

An Important Distinction

A scientific study can be motivated, designed, and even led by local communities. Communities sometimes have the most urgent reasons to know more about their environments. They can collaborate with professional scientists to find the answers, but the community still decides on what the question is. Practitioners around the world call this type of work community science. The National Park Service distinguishes it from citizen science, where the park or the scientist asks the question and enlists volunteers to collect data to help answer it.

What might a park-related community science project look like? It could resemble the scene above. But this time the scientist would be the volunteer, and the others in the field might be local community members and park staff. The team would be sampling sediments because the community prioritized that and the park agreed. Study sites would be places the community helped select, perhaps both inside and outside the park’s boundaries. The data would help community members better understand their environment and assist them in solving a problem they thought important. And it wouldn’t necessarily matter to the community whether or not a peer-reviewed scientific journal published the findings.

The National Park Service recognizes the value and legitimacy of community science, because parks are public spaces that share landscapes, history, and environments with countless communities.

The National Park Service recognizes the value and legitimacy of community science, because parks are public spaces that share landscapes, history, and environments with countless communities. To support community science, the agency has a formal agreement with the American Geophysical Union’s Thriving Earth Exchange. The exchange facilitates community science worldwide. It solicits communities who want to address their highest priorities through science, connects them to professional scientists who volunteer their time and expertise, and provides seed funding for projects. It also recruits and trains people to serve as community science fellows.

Fellows are project coordinators and liaisons who connect all the parties and keep things moving forward. Under the agreement, National Park Service employees can serve as fellows as part of their regular professional duties. In the past two years, five agency employees have signed on as fellows, including three of us. Here we share our experiences with this new and exciting way to do science and reflect on what it means for employees, parks, and communities.

Image credit: NPS

Claudia Santiago’s Story: Science in the Service of Social Justice

My name is Claudia Santiago. When I started as a Thriving Earth Exchange fellow, I was a biological science technician at Congaree National Park. My colleagues from the Congaree Biosphere, of which the park is a part, were David Shelley, manager of Congaree’s Integrated Resources Program, and Tameria Warren, an adjunct professor in the School of the Earth, Ocean & Environment at the University of South Carolina.

Hopkins had a history of people being displaced from their property because of gentrification.

On a hot, humid summer morning in July, the three of us attended a barbecue in Hopkins, a community in Lower Richland County. Community leader Kristen Porter hosted the event. The purpose of this meeting was to answer two questions: How can Congaree National Park and the local community work together to design sustainable solutions to mutually important environmental issues? How can the park use science to support community goals?

The barbecue was delicious, but the community’s problems were tough. Hopkins had a history of people being displaced from their property because of gentrification. The landscape was changing, losing the rural character its residents valued. Now folks were facing a newly proposed sewer system, which would increase their monthly utility bills significantly for a service they felt they did not need.

I began the conversation, my heart going to my throat, feeling hot in my uniform hat. Although I had already collaborated with communities neighboring the park on other projects, I was still an outsider, here to talk about well-known problems the community deals with daily. I grew up in a low-income, immigrant family in El Paso, Texas, and I knew how outsiders affected my community. But the few seconds between my last words and the community’s first comments felt like a lifetime. All I could hear was my leather boots squeaking as my toes wriggled nervously.

Rooted by Place and History

After I spoke, community leaders shared their opinions of the new sewer system and raised public health concerns about malfunctioning sewage pumping stations in flood-prone areas. Their comments made me think of some remarks South East Rural Community Outreach (SERCO) Chair Marie Barber Adams made to me. Adams is a retired educator and member of a landowner family that’s been in the Lower Richland area since 1872. She said Congaree is located on some of the land formerly owned or used by African American families like hers. The families are still rooted in the community because they cherish and honor its history and understand the importance of “preserving the history of the land and how it was able to sustain them."

During the reconstruction era, many freed slaves, like Adams’s great grandparents, Harriet and Samuel Barber, purchased tracts of land in Hopkins from the South Carolina Land Commission. The Barber family and other African Americans in Lower Richland County developed a sense of ownership. They channeled this into developing land-use practices, agricultural organizations, and fishing traditions that supported a stable and prosperous community. Adams and other community leaders actively preserve African American history in Hopkins with support from SERCO and scientists like Warren.

Although the new sewer system could provide better sanitation, both the community and the park were concerned it could result in more development, gentrification, and habitat degradation.

As one of Congaree’s biological science technicians and a citizen science coordinator, I knew the park’s concerns were similarly complex and longstanding. An agricultural legacy and poorly maintained septic systems across Lower Richland have contributed to contaminants like pharmaceuticals, agricultural chemicals, and fecal coliform bacteria entering the park’s waterways. These chemicals and pathogens threaten human health and the park’s aquatic ecosystems. Congaree gets about 150,000 visitors annually, who collectively spend millions of dollars per year to hike, camp, paddle, and fish in the park. My colleague, David Shelley, said pollution “has the potential to impact visitor experience” as well as the park’s appeal and income.

As the early afternoon approached and the barbecue wrapped up, my initial fear turned into excitement. I realized how I could help the park and the community meet their shared goals through science. Growing up, I had experienced economic hardship and marginalization that shaped my views of the world, making me focused on trying to solve the big challenges at the core of gentrification. I felt that this background and my scientific training could help in a way that would be relevant to the reality and cultural values of the Lower Richland community.

Although the new sewer system could provide better sanitation, both the community and the park were concerned it could result in more development, gentrification, and habitat degradation. The resulting potential increase in harmful contaminants in water or fish could affect the health of local anglers. Urbanization, stormwater runoff, pesticides, and pharmaceuticals could amplify, reducing the area’s environmental quality.

After weeks of collaboration, SERCO, Congaree, and community leaders proposed a water quality monitoring program. It would be an interdisciplinary project informed by knowledge passed down through generations, local decision-makers, resource users, and community members. As a community science fellow, the park chose me to manage the project. I began a humbling yet life- and career-changing journey of reciprocal learning with a fantastic team and community.

Image credit: NPS / Paul Angelo

A Wealth of Local Knowledge

Adams, Warren, and I worked together to develop a visual protocol for assessing stream quality. We knew that generational knowledge from local communities would be key to establishing the project's relevance. In 2022, we organized four public meetings around Hopkins. We asked attendees questions like these: What are their strengths and capabilities? What are they most proud of? What have they accomplished to improve water quality in their streams? What ideas do they already have about monitoring water quality?

The first meeting was in April 2022. It was a virtual meeting, held on a Saturday. This was because we wanted to encourage participation by young people and those who didn’t have access to transportation. I distributed flyers in local stores, libraries, recreation centers, and post offices around Lower Richland weeks before the meeting. Despite my “Zoom fatigue” after months of virtual meetings, I was excited to join the videoconference. We were pleasantly surprised that several prominent community members attended: an assistant professor who leads community efforts to tackle long-term stormwater issues, a retired professor focused on environment health outcomes for African Americans, and a minister from one of Hopkins’ churches. I learned from them the importance of finding leaders who will help spread the word.

“We have to come to a point that there's a real clear marriage between not only understanding the science but also the application,” said one participant. Another said she added bleach to her well water because she was worried factories near her home had contaminated it. Knowing the science won’t make a lot of difference unless people see how it can improve their lives. And no matter how removed from the affected community, scientists want to make a difference.

By stepping out of the park's boundaries to talk to the community, we were making a difference. We were also deepening our own understanding of the park’s water quality issues.

We also attended the annual sweet potato festival, the Juneteenth event at the Harriet Barber House. For the festival, I developed a game that asked people to pick the best fishing hole in Congaree from photos. Local fishermen were able to identify the best habitat for fish based on the color, depth, and water current of the streams in the park.

“Community members have a lot to share,” Warren observed after our last meeting in August. “While they may not know all of the technical details, they bring a wealth of knowledge that leads to viable solutions." We think our discussions helped the community better understand what they were up against. By stepping out of the park's boundaries to talk to the community, we were making a difference. We were also deepening our own understanding of the park’s water quality issues.

Supporting a community science project taught me that working with local residents at all stages of a project helps to guide the scientific process. This is valuable for ensuring the results are relevant and meaningful to the community. But balancing scientific, community, and agency interests at different stages of community science can be challenging. Scientists and community members operate with different cultural norms, expectations, and ways of expressing themselves. I quickly learned the importance of making sure we were all in agreement about purpose, desired outcomes, and expected involvement.

Although many scientists come to Congaree to do research and collect data, I wonder how many think about the people who live around it.

When I presented the first draft of the visual assessment protocol at the South Carolina Water Resources Conference in October 2022, I remembered the pressure from the science community to focus on publishing papers, seeking funding, and claiming intellectual property. But community science is not only about advancing scientific knowledge. It is also about increasing access to science, improving people’s living conditions, and supporting different ways of knowing.

Tim Callahan is chair of the Department of Geology and Environmental Geosciences at the College of Charleston and an advisor for the project. "Scientists should come to important collaborations like these with a humble heart and open mind,” he said. “Community members have a lot of knowledge and experience, and their contributions benefit the environment and…the entire community." Although many scientists come to Congaree to do research and collect data to monitor the park’s ecosystem and ensure its preservation, I wonder how many think about the people who live around it.

Image credit: NPS / David Shelley

The people of Hopkins have objectives, interests, and priorities. The community views science as a way to increase social justice by giving them the knowledge and data they need to ask effective questions, ones that help protect their heritage, land, and generational ecological knowledge. Through the process, community members asked about the science behind water quality monitoring, but they also wanted to know how the National Park Service works. They often asked me pointed questions: Why can’t a biological science technician work directly with tribes? Why can’t I speak out against local industries that are marginalizing communities? Why can’t I tell companies to take responsibility for their pollution? Through this, I became aware of the challenges park managers face. Legal, policy, or financial constraints, or competing issues, can complicate a park’s ability to support community science.

Stronger Together

This Thriving Earth Exchange project is challenging scientific, societal, and agency norms to create a more sustainable future. Its backbone is the people of the Lower Richland community. The visual stream assessment protocol moves science out of the park and into a framework accessible to everyone. Chemical and biological monitoring are effective in monitoring stream health but require expensive sensors, supplies, and expertise. On the other hand, a visual assessment—if calibrated correctly—can easily be used by community members to monitor water quality. By transforming the way they do science, scientists can form relationships, build trust, and gain vital knowledge to better protect park resources.

Chemical and biological monitoring require expensive sensors, supplies, and expertise. On the other hand, a visual assessment can easily be used by community members to monitor water quality.

In March 2023, we hosted a symposium to discuss the visual assessment protocol’s scientific accuracy and appropriateness for the streams around Congaree and the Lower Richland community. Scientists from several state and federal agencies attended, and new opportunities for collaboration surfaced. Agencies and institutions who attended the symposium are now working together to sample aquatic insects at Congaree’s stream monitoring sites. Some have begun a study to update the national water quality standards for South Carolina’s blackwater streams—those that run slowly through forested swamps. Members of the Congaree Biosphere Region and the University of South Carolina have begun to develop a water quality monitoring program for high school students.

Warren said community science projects assure residents that their voices will be heard when devising ways to protect natural resources. She added that this collaboration “can enlighten us about any potential dangers or harmful elements in our local environment.” This benefits everyone and tangibly demonstrates that we are all working toward a safe, healthy, and promising future for generations to come.

Image courtesy Tammy Binder

Image credit: NPS

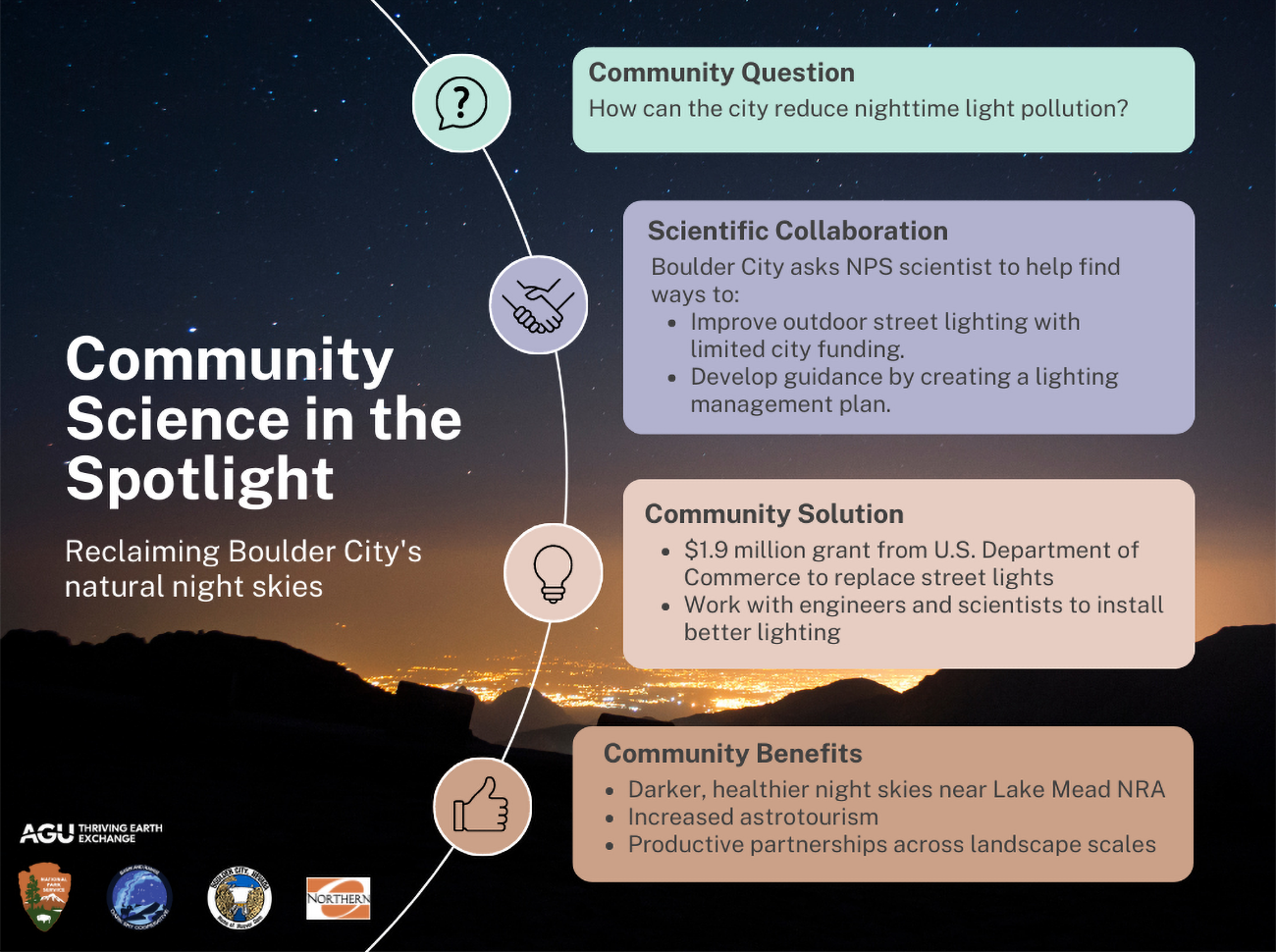

Ashley Pipkin’s Story: Bringing Back the Stars

My name is Ashley Pipkin. I am an outdoor recreation planner with the National Park Service’s Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division and a Thriving Earth Exchange fellow. Among other projects, I am helping one small community, Boulder City, Nevada, reclaim its dark, star-filled night skies. Boulder City is a desert mountain town of 16,000 people in southern Nevada. It is best known as the home of the massive Hoover Dam, which created Lake Mead and is one of the world’s most iconic structures and a national historic landmark.

Those stars still shine over Boulder City, but they’re a lot harder to see now.

This Depression-era engineering marvel still provides electricity to streetlights throughout the city. In Monument Plaza at Hoover Dam, you will find a star chart noting what the cosmos looked like on the day the dam was completed. Those stars still shine over Boulder City, but they’re a lot harder to see now.

Reducing light pollution means improving outdoor lighting inside park boundaries and working with partners outside of park boundaries. Those partnerships create a sense of shared stewardship across landscape scales. In 2019, I began to coordinate the Basin and Range Dark Sky Cooperative, a group of stakeholders who share resources and collaborate to improve night skies. In 2021, the Boulder City Chamber of Commerce started joining cooperative meetings. They wanted to protect the city’s natural night skies and expand astrotourism.

When the city first installed LED streetlights on Utah Street in 2017, it found itself in the same position as so many communities across the developed world. The city expected energy-efficient LED outdoor lighting to reduce its carbon footprint—ostensibly good for the planet. But it created another problem: too much light at night. This was bad for wildlife and people. The community noticed.

Background image credit: Getty Images / nukleerkedi

Four years later, I gave a presentation to the Boulder City Council about the benefits of natural night skies and how to decrease artificial light at night by using appropriate fixtures. By this time, the city had retrofitted a little under half of its streetlights. I showed residents how to reduce their carbon footprint and also reduce light pollution. The two goals were not mutually exclusive. After my presentation, the community decided it wanted to save money and bring back the stars for residents and tourists. I teamed up with city staff and the chamber of commerce to begin a Thriving Earth Project that would respond to community needs. That’s when my real work in community science began.

The U.S. Department of Commerce awarded a 1.9 million dollar grant for Boulder City to retrofit its outdoor street lighting.

Changes were needed but cost was a concern. But through our partnership with the Nevada Division of Outdoor Recreation, the U.S. Department of Commerce awarded a 1.9 million dollar grant for Boulder City to retrofit its outdoor street lighting. These new lights will meet community needs while creating darker night skies and more opportunities for astrotourism. We are currently working on a lighting management plan and deciding on the right technology for the town. Being a Thriving Earth Exchange fellow has given me the opportunity to help create win-win situations for Lake Mead National Recreation Area and its gateway community. It’s an incredibly rewarding experience to see the very first lights installed from our work. We know we’ll be bringing back the night to the community and reducing our impact to vast expanses of neighboring public lands.

Image courtesy of Robert Walls

Image credit: NPS / Jay Elhard

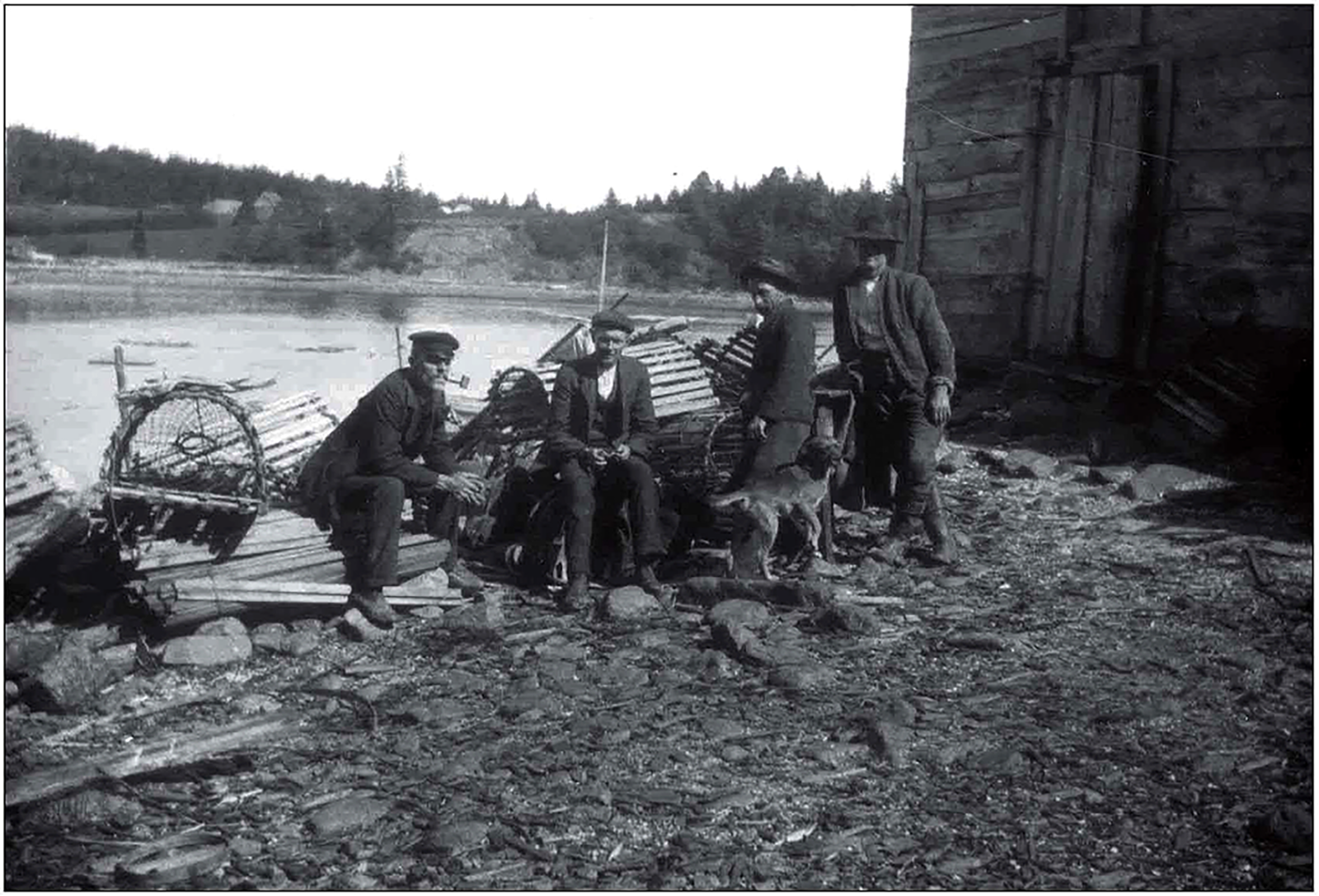

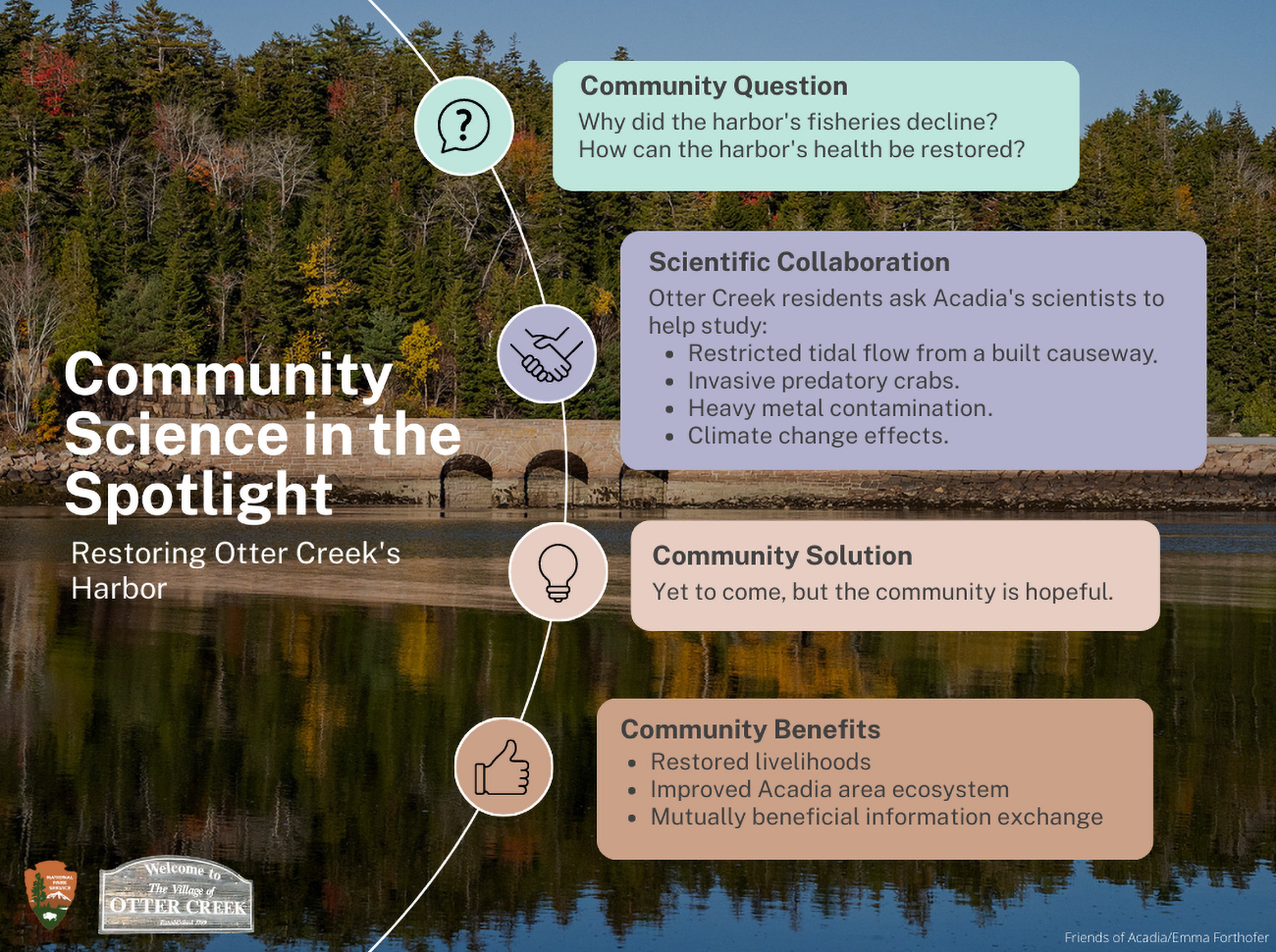

Abe-Miller Rushing's Story: Comeback Hopes for a Lost Fishery

My name is Abe Miller-Rushing. I am a science coordinator at Acadia National Park and a Thriving Earth Exchange community science fellow. I oversee most of the research in the park and work with communities around the park on mutually important issues. One community I work with is Otter Creek, once a bustling fishing village on Mount Desert Island, Maine.

Over the past century, fishing areas have been cut off, and the catch in the cove has plummeted.

The village sits at the head of Otter Cove, a long, narrow harbor that once opened to the Atlantic Ocean. In the past, it provided local residents access for catching fish, lobsters, and clams. But over the past century, fishing areas have been cut off, and the catch in the cove has plummeted. The local community wants to know why and what can be done to bring the fisheries back. Scientific studies can help us sort this out.

During the Great Depression, in the 1930s, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., bought land around Otter Cove and donated it to the National Park Service to expand Acadia National Park. He also helped lead the design and construction of the causeway that allows the scenic park Loop Road to cross the harbor. As a result, the village of Otter Creek lost most of its access to the waterfront, and the harbor no longer opened to the ocean freely. Tidal flow in and out of the harbor was restricted to three arches in the causeway, which do not allow vessels much larger than a rowboat to pass through.

Otter Cove’s fisheries are not the only ones in trouble. The area’s larger fishing industry is facing many other pressures. Fish stocks have declined across the region, and businesses have shifted to larger boats. Climate change has warmed the harbor’s water, made it more acidic, and brought more frequent and larger storms. Invasive green crabs, native to Europe but foreign to these shores, have become abundant. They have caused native clams and other native marine species to decline by preying on them. And for a short time, a water treatment plant released heavy metals into the harbor.

In 2021, Durlin Lunt, the town manager, asked Acadia National Park to help determine specifically how all these factors have contributed to the decline in biodiversity and overall health of Otter Creek harbor and its fisheries. He also wanted to work with park staff and scientists to identify potential solutions. The National Park Service’s partnership with Thriving Earth Exchange started about the same time, giving me a great opportunity to work with the community and scientists to answer that question.

Background image credit: Friends of Acadia / Emma Forthofer

We—town leaders and park staff—began by meeting with community members to hear what they most valued about the harbor. We wanted to know what problems they were seeing and what potential solutions they envisioned. Then we partnered with scientists at the College of the Atlantic and the Schoodic Institute to gather and assess historical records. We also did some preliminary fieldwork and outlined options for further research and actions to take. At another town meeting, we presented the results of our investigations (as yet unpublished) to the people of Otter Creek and heard their thoughts on what our next steps should be.

Preliminary evidence suggests the causeway is helping to make the inner harbor excellent habitat for exotic green crabs, which eat native clams.

They asked the town and the National Park Service to assess impacts of the causeway on tidal flow, investigate the impacts of green crabs on clam populations, and test sediments for heavy metal contamination. As we do this, we will also look into interactions among these factors. For example, preliminary evidence suggests the causeway is helping to make the inner harbor excellent habitat for exotic green crabs, which eat clams. The inner harbor has some of the highest densities of green crabs on Mount Desert Island and very few clams, whereas the outer harbor has far fewer crabs and more clams. The town and park staff will continue collaborating to investigate these issues. We will incorporate our findings into the park’s climate adaptation plans. Our ultimate goal is to take steps to improve the health of the harbor ecosystem and its value to the community.

Image credit: NPS / Karen Zimmerman

Looking Outside Parks for Inside Knowledge

National parks and their local communities are affected by the same environmental processes and impacts. They may have similar priorities and concerns. The National Park Service already reaches out to gateway communities on conservation, recreation, and education. The agency can further fulfill its mission through collaborative scientific studies with communities. When these studies focus on issues the communities prioritize, science benefits from the residents’ generational knowledge of their environment. And residents benefit from increased scientific attention to their most pressing issues. As co-author Pipkin says, it’s a win-win situation for everyone.

About the authors