Last updated: February 28, 2025

Article

Using Their Voices: Founding Women of National Parks

In a country built on the concept that voting is the ultimate act of civic engagement, ratification of the 19th Amendment not only codified voting rights for women, it also signaled something even deeper: it affirmed the public role of women in our nation’s social, civic, and policy-making realms.

In 2020, as we commemorated both the centennial of the 19th Amendment and the 104th birthday of the National Park Service, we highlighted a few women who harnessed their public voices to protect extraordinary American places. From rich, naturally diverse ecosystems and landscapes to sites that call on us to be strong stewards of our nation’s future, today these places are units of the National Park System.

Marjory Stoneman Douglas | Everglades National Park

For many, the Everglades in southern Florida was nothing more than a vast swamp that, once drained, could be something much more “useful.” But Marjory Stoneman Douglas recognized the serious, consequential damage caused by changing the Everglades’ natural systems, especially the natural water flow. She was vocal in her disapproval and distaste for the destruction of the scenic wetlands. She knew that restricting natural water flow results in very little support for vital algae growth, a lack of oxygen dispersal necessary for many aquatic animals to thrive, and a decrease in open water feeding areas for wildlife.

Marjory Stoneman Douglas was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 1890. After graduating from Wellesley College with honors, she was a journalist for the Miami Herald and dedicated herself to conversations about feminism, racial justice, and conservation. Douglas was particularly devoted to the Florida Everglades, which she affectionately called “her river.” She fiercely defended it long before scientists recognized the negative effects of agricultural and real estate development on the intricate ecosystem.

In 1947, Douglas wrote The Everglades: River of Grass. Her book described the immense importance and beauty of the natural ecosystems of south Florida and the need for protection from human interference. That same year, Everglades National Park was established. Douglas and her passionate, unwavering advocacy for Everglades conservation played a significant role in establishing the park. She continued to represent the park as the founder and head of the Friends of the Everglades, an organization dedicated to preserving, protecting, and restoring Marjorie Stoneman Douglas’s river.

Maggie L. Walker | Frederick Douglass National Historic Site

Maggie Lena Walker was born in the Confederate capital city of Richmond, Virginia, in 1864—the last year of the Civil War. Her mother had been born into slavery but was free by the time of her daughter’s birth.

Walker was a teacher until she married and became a valued member of the local council of the Independent Order of St. Luke, a national fraternal society devoted to caring for the sick and aged in the African American community. She rose through the ranks, eventually holding the top leadership position, and established a national newspaper called the St. Luke Herald to elevate African American voices and promote a deeper relationship between the Order and the public. Recognizing the economic challenges her community faced, Walker founded the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank and served as the bank’s first president, making her the first African American woman to charter a bank in the United States.

Maggie Walker was also very involved in civic groups throughout her life. As a dedicated advocate for African American women’s rights and the education of children, she held leadership positions in the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) and the national NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) board.

Five years after abolitionist, suffragist, and activist Frederick Douglass passed away in 1895 and at the persistent urging of his widow Helen Douglass, Congress chartered the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association (FDMHA). Walker joined the FDMHA board of trustees and she, along with many other prominent women from around the country including Mary McLeod Bethune, worked tirelessly to make Douglass’ Washington, DC, home, Cedar Hill, a memorial open to the public. After the restoration of the house and documentation of Frederick Douglass’s impressive pursuit of equality and life of activism, the Frederick Douglass estate became a unit of the National Park System in 1962.

Walker’s role in the founding of the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site was part of her lifelong engagement in improving her community through social change and civic participation and in promoting Black excellence through her public leadership. Today her home in Richmond and the Council House in DC where Walker’s friend, Mary McLeod Bethune, worked with the National Council of Negro Women are also units of the National Park System.

Sue Kunitomi Embrey | Manzanar National Historic Site

Like Maggie Walker, Sue Kunitomi Embrey understood the need to recognize and protect places that are powerful parts of our national memory and used her civic voice to advocate for those places.

And, like Walker, this knowledge came from personal experience.

Embrey was born in the Little Tokyo neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, in 1923. When she was 14, her father was killed in a truck accident, and her mother struggled to provide for her eight children. After high school, Embrey stayed home to help her mother run their family store.

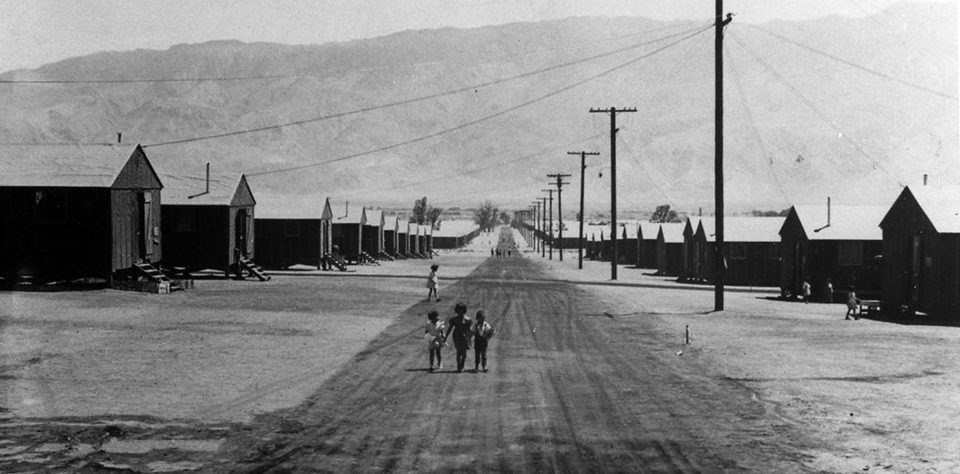

In 1942, after the start of World War II, the federal government ordered more than 110,000 men, women, and children—none convicted of espionage or sabotage—to leave their homes and detained them in remote, military-style camps. Embrey and her family were sent to the Manzanar War Relocation Center, one of 10 camps where Japanese American citizens and resident Japanese aliens were incarcerated during the war. She was 19.

After the war, she went to college and received a master’s in education. In 1969, Embrey attended the first Manzanar pilgrimage and spoke publicly about her wartime experience. Then, as the co-founder of the Manzanar Committee and eventual chair of the board, Embrey organized the next 37 pilgrimages and successfully led the campaign that resulted in Manzanar becoming a California historic landmark in 1972 and a unit of the National Park System in 1992. Sue Kunitomi Embrey passed away in 2006 at the age of 83.

Throughout her life, Embrey served as an advocate for preserving and remembering Japanese American incarceration narratives. In Embrey’s opinion, conserving Manzanar and retelling the stories of the WWII Japanese American incarceration camps are important to ensure that it doesn’t happen again.

“It might happen to another group of people or people with different political beliefs,” she said. “And it’s important for us to remember that we have a Constitution, a written document that is only good when people make use of it. And they have to use it, and not abuse it.”

Embrey dedicated her adult life to civil rights and to honoring the stories of Manzanar, noting “Liberty is something very precious we all need to work for and to strengthen.”

NPS photo

Betty Reid Soskin | Rosie the Riveter / World War II Home Front National Historical Park

Retiring at age 100 n 2022, Betty Reid Soskin was the oldest serving park ranger. Soskin knows well the park that she served and knew it when the park idea was forming and long before that. She was a Home Front worker in a place that became Rosie the Riveter / World War II Home Front National Historical Park.

Soskin was born in Detroit, but her parents were from Louisiana. She lived in New Orleans as a child. Her great-grandmother, who lived to be 102, was born into slavery. Soskin’s family moved to Oakland, California, when she was a girl. She tells the story of taking the train to and from Louisiana to visit family, noting that there was a point along the trip when Black customers had to move to the back of the train.

During World War II, Soskin worked in Richmond, California, as a clerk in the Boilermakers Union A-36, a Jim Crow all-Black union auxiliary. As the war effort meant that women joined factory workforces, they were celebrated on posters as Rosie the Riveter. But, as Soskin noted, the advertising campaign reflected “a white woman’s narrative” and excluded the very different Home Front experiences of Black women and other women of color who contributed greatly to the war effort across the U.S.

“What gets remembered is a function of who’s in the room doing the remembering,” said Soskin. As a new park began to take shape in the old shipyards of Richmond to recognize the home-front role of Rosie the Riveter, Soskin was in the room. As a staffer for local state assembly members, she was involved in the park planning effort and ensured that it reflected a wide diversity of stories, including hers.

Soskin continues to use her voice, telling her story as a personal reflection of the broad African American experience and what it means for our nation’s future.

-------

For each of these women, and countless others before them and still to come, their engagement and advocacy sprang from their passion and vision for these important places. Their accomplishments and the protection of these places resulted when they raised their public voices and led the charge...just like the suffragists’ work itself ensured that women’s voices would not be silenced.

Tags

- everglades national park

- frederick douglass national historic site

- maggie l walker national historic site

- manzanar national historic site

- mary mcleod bethune council house national historic site

- rosie the riveter wwii home front national historical park

- women's history

- nps birthday

- 19th amendment

- park history

- women of the nps

- historic women of the nps

- education history

- economic history

- african american history

- florida

- virginia

- authors

- political history

- journalism

- washington

- dc

- california

- asian american history

- japanese history

- japanese american history

- world war ii

- civil rights

- labor history

- nps history