Last updated: July 7, 2022

Article

Uncovering Ral City

Discover how a large squatter's camp called Ral City influenced Hot Springs to become Spa City, a 20th century health destination.

Courtesy of the Hot Springs National Park Archive

Who deserves the right to access the hot springs?

Hot Springs National Park protects the thermal spring water that flows from the base of Hot Springs Mountain and preserves the history, the culture, and the stories that surround them. During the early 19th century, Hot Springs underwent a dramatic transformation from a remote place in the frontier to a premier tourist destination for health and healing. The thermal springs were believed to have healing properties that could bring about relief for a wide variety of ailments. As the springs grew in popularity and public demand for bathing increased, conflicts arose over who had the right to access the springs. Should only patrons who could afford to pay for bathing services be allowed to use the springs? What about those who were poor and could not afford the services they needed? Between 1868 and 1878, events would unfold that brought about an answer to this question.Water Cure Craze

By 1820, a small village of permanent residents had established themselves around the hot springs. They offered room and board for a modest price to those who made the trek to bathe in the springs. Many who traveled to Hot Springs were in search of a “miracle cure” that could offer them some form of relief. Even though the thermal springs are not curative, many did feel better after soaking in the hot water. Medicine in those days was much different than what we are familiar with today – for context, Penicillin wasn’t discovered until 1928 – so medicinal treatments of that time seldom provided a cure for diseases or ailments. Early entrepreneurs quickly realized the value of marketing the thermal springs as a “cure all.,” This paved the way for a western frontier town in the newly formed Arkansas Territory to become a tourist hot spot and an entrepreneur’s dream for private development. At the same time, the practice of hydropathy, or the treatment of illness through water, swept the nation. People traveled far and wide just to bathe in the thermal springs.

"Some forty of fifty [patients] are now here, most of them affected with rheumatism and mercurial complaints, in which diseases the astonishing efficacy of the baths is discernible. I see several who are arrived, lifted as inanimate beings, now walking with agility. There are others who had taken a good deal of mercury, and whose systems were not cleansed of it, until they bathed here some weeks, when a profuse salivation occurring, and continuing from two to four weeks, every vestige of disease was removed."

-Hot Springs observer in 1846

What lengths would you go to for better health?

Courtesy of the National Archives

Congressional Protection of the Hot Springs

After the Louisiana Purchase in 1804, President Jefferson sent an expedition team led by George Hunter and William Dunbar down to the newly acquired territory. Upon their return, Jefferson and the nation learned about the “hot springs of the Washitas.” As news about the thermal springs spread, the federal government recognized the value of the resource and the need to protect them in perpetuity for public benefit.

Follow the timeline below to learn more about how the springs were protected.

1818

The Quapaw Tribal leaders agreed to a treaty that ceded a portion of their land, including their hunting area around the hot springs, to the United States. This was the first in a series of treaties that allowed European Americans to explore and exploit the hot springs.

1820

The General Assembly of the Arkansas Territory sent a petition to the U.S. Congress requesting that the thermal springs be protected. They said, "...Section be granted to the local Legislature, to include all the Hot Springs for benefit of that watering place...as may be directed by the general assembly of Arkansas - The land about the Hot Springs is extrem[e]ly poor and worth very little for farming purposes..." The request went unfulfilled, leaving the hot springs in legal limbo.

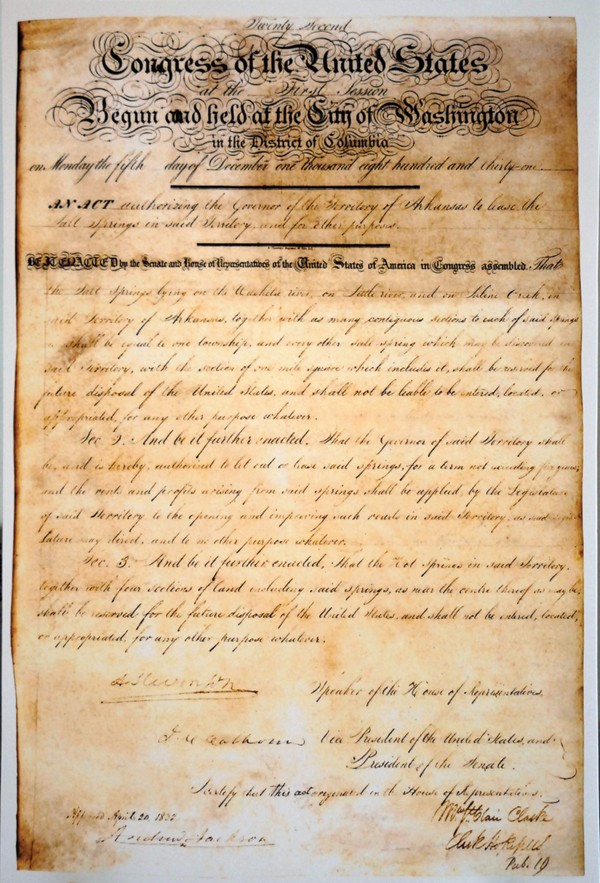

1832

Congress passed legislation for President Andrew Jackson’s signature that established “Hot Springs Reservation” which set aside the land around the hot springs for public use. However, Congress did not establish a way for the federal government to monitor the land and maintain oversight and control over its use. In effect, this left the land open, and private individuals continued to lay claim to sections of the Reservation for personal gain.

1836

Arkansas became the 25th state in the Union. Realizing the growing intrigue and potential of the hot springs, Representative Ambrose Sevier requested that the title to Hot Springs Reservation be granted to the newly formed state. His request was denied.

1849

The Department of the Interior was created, and Hot Springs Reservation was moved under its authority. The Reservation still had no federal oversight, and disputes between claimants started to grow.

1851

The City of Hot Springs was incorporated and featured a main central avenue, many hotels, dozens of bathhouses, stores, saloons, a doctor’s office, and private homes. Bathhouse owners and shop keepers continued to petition the Federal Land Claims Office for the deed to “their” land within the federal Reservation. Hostility and tension continued to rise, sometimes leading to violence.

Courtesy of the Hot Springs National Park Archive

Hot Springs Reservation's Early Years, 1860 - 1865

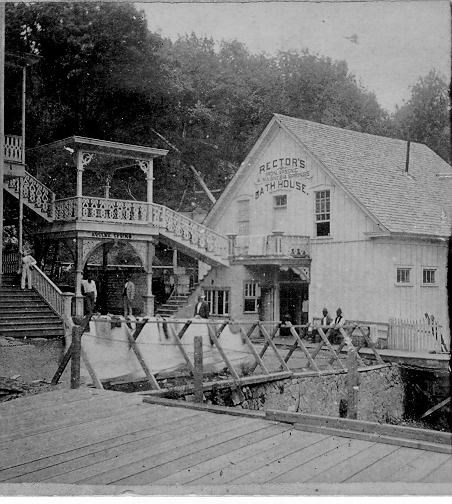

Early Bathhouses

In the early 1860s, Hot Springs became one of the most popular destinations in the South. Spas and bathhouses lined the East side of Hot Springs Creek. Some of these early establishments included the Old Hale Bathhouse, the Rector-Hale Bathhouse, the Rector-Hale-Clayton Bathhouse, two more Clayton Bathhouses, the Slab House, and the Warren Bathhouse. As crowds poured into town, the demand for bathing was high and drove up the cost to take a bath. With increased visitation, vices such as gambling, alcoholism, and prostitution exploded.

"Every nook and corner is so filled with visitors that they will occupy the parlor floor until some one [sic] leaves the Springs, when they hurry into the vacant room." - reported from an observer in 1860.

During this same time period, slavery in Hot Springs multiplied. Enslaved Black women served as laundresses, maids, and cooks while Black men were put to work in hotels and bathhouses as attendants and porters. Hotels even advertised that enslaved people were welcome to come and “take the cure” and once restored to health, be sent back to their masters. Enslaved Black laborers were the backbone of the local economy and were unfortunately regarded only as “income-generating property.”

Civil War

During the Civil War, travel from the North and East came to a halt and the first wave of prosperity in Hot Springs evaporated. Towards the end of the Civil War, the city was ransacked and nearly burned down, devastating the spa-driven economy. In 1865, the Civil War came to an end with the surrender of the Confederacy.

Slowly, as travel resumed and veterans of the war sought healing and relief, Hot Springs started to bounce back. The growing demand for bathing services and facilities led land claimants to enlarge their hotels and bathhouses and build new bathhouses to accommodate the increasing number of paying guests.

Hot Springs National Park Archive Collection

Establishing Ral City

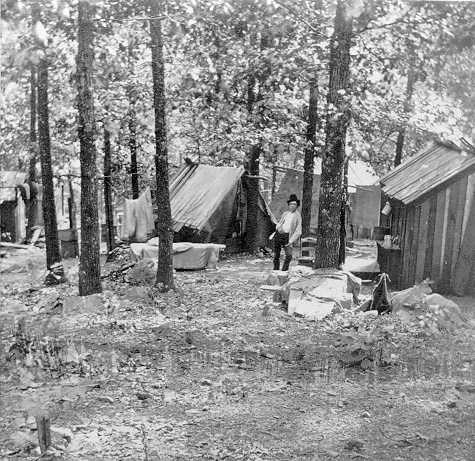

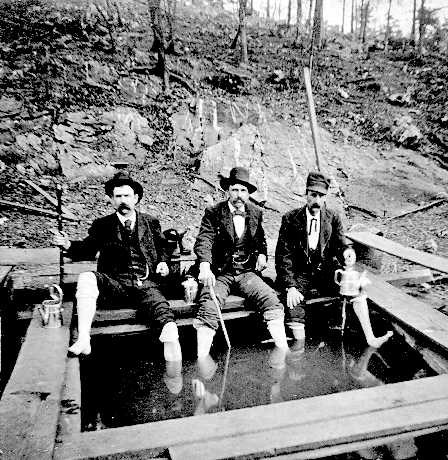

Out of sheer desperation, Civil War veterans and private citizens alike made their way to Hot Springs. Because they could not afford to live in the booming town or pay for bathing services, they created makeshift “dug-out” pools on Hot Springs Mountain around the thermal springs and built makeshift campsites. One such campsite was named, “Ral City.” Ral was a term short for neuralgia, a nerve disorder caused by several conditions, including syphilis. The dug-out pools took on a life of their own and were named for their proclaimed healing abilities: Corn Hole Spring was for soaking feet; Mud Hole Spring was for the poor; and Ral Hole Spring was for impoverished people with syphilis.

The Hot Springs Cases, 1875 - 1878

Who will take possession of the hot springs?

Finally, after nearly half of a century, claim disputes over land around the hot springs are considered by the federal government.

Follow along in the timeline below to watch the series of events unfold.

1875

The U.S. Court of Claims ruled against all claimants seeking to take possession of the springs. The claimants appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, but even there, the court upheld the ruling. This ended the claim disputes and allowed the federal government to take control of the land.

1877

Colonel Samuel W. Fordyce was a Civil War veteran and prominent Hot Springs citizen who was responsible for much of the town’s economic growth after the Civil War. Fordyce tried to convince outgoing President Ulysses S. Grant to sign a Congressional Act creating a “Hot Springs Commission” made up of 3 individuals who would be tasked with surveying Hot Springs Reservation and redrawing federal boundaries. Grant was skeptical of the bill and believed that it was “dangerous and gave too much power to the three commissioners.” Fordyce continued to appeal Grant’s decision. He made it clear that the residents of Hot Springs were very poor, and they incessantly fought over ownership rights of the Bathhouses and lands they had developed for decades.; Fordyce believed that redrawing the federal boundary and completing a survey of the land would help the town, its people, and the Reservation. Grant agreed to sign the bill if President-elect, Rutherford B. Hayes, appointed men of “integrity and honesty” to the Hot Springs Commission.

1877

Newly elected President Hayes appointed three commissioners: John Coburn, Aaron H. Cragin, and Marcellus L. Stearns. He also brought Chief Engineer A.P. Robinson, and a small staff of surveyors into the project. The Commission was given broad control over Hot Springs Reservation; they assumed control over the thermal water and the town.

1877

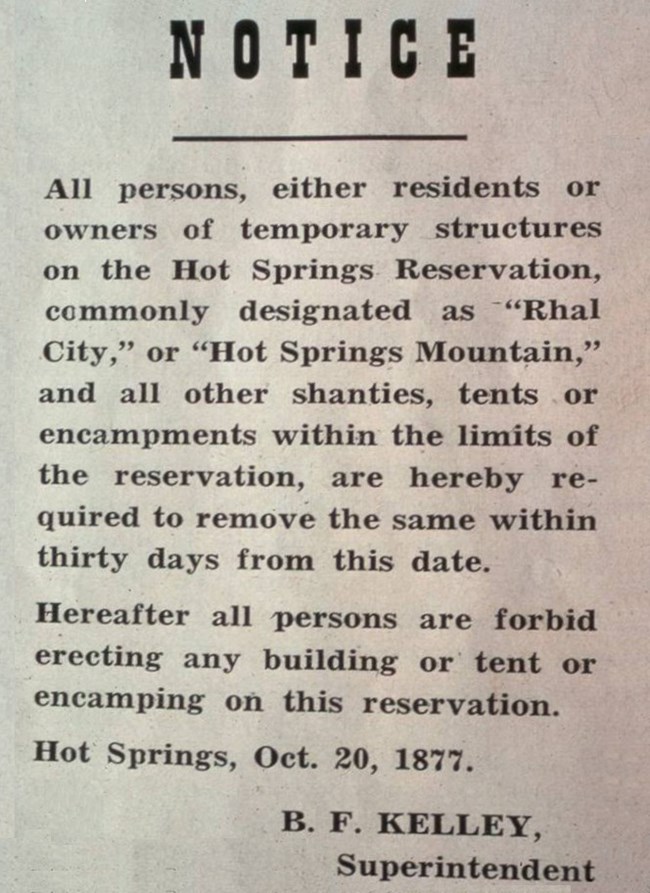

Secretary of the Interior, Carl Schurz, appointed General Benjamin F. Kelley to be the first Superintendent of Hot Springs Reservation. Kelley worked in close cooperation with the Hot Springs Commision and provided regular reports on their progress to the Secretary of the Interior.

NPS image from park archives

Meet Benjamin F. Kelley (1807-1891)

Benjamin F. Kelley was a retired US Army officer. During the Civil War, he spent most of his service protecting the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad lines across West Virginia and Maryland. After his resignation from the service, President Grant gave Kelley the position of ‘Collector of Internal Revenue for West Virginia,’ where he worked until his appointment as the first Superintendent of Hot Springs Reservation.

Courtesy of the National Archives

Taking Charge

By 1877, over 400 people had created encampments along the western slope of Hot Springs Mountain. Their mudholes and dugouts raised problems with the bathhouses below who claimed that Ral City’s access to the springs was impeding their ability to do business. The complaints prompted government intervention and one of Superintendent Kelley’s first tasks was to remove Ral City. Kelley distributed leaflets (shown right) and gave everyone 30 days to clear out. However, many who had joined Ral City were too disabled or ill to leave. Kelley soon realized that these people had nowhere else to go and needed access to the thermal waters; so, he came up with a plan – to build a free bathhouse. Kelley went around the town and solicited donations from the community to build a free bathhouse and help clean up Ral City.

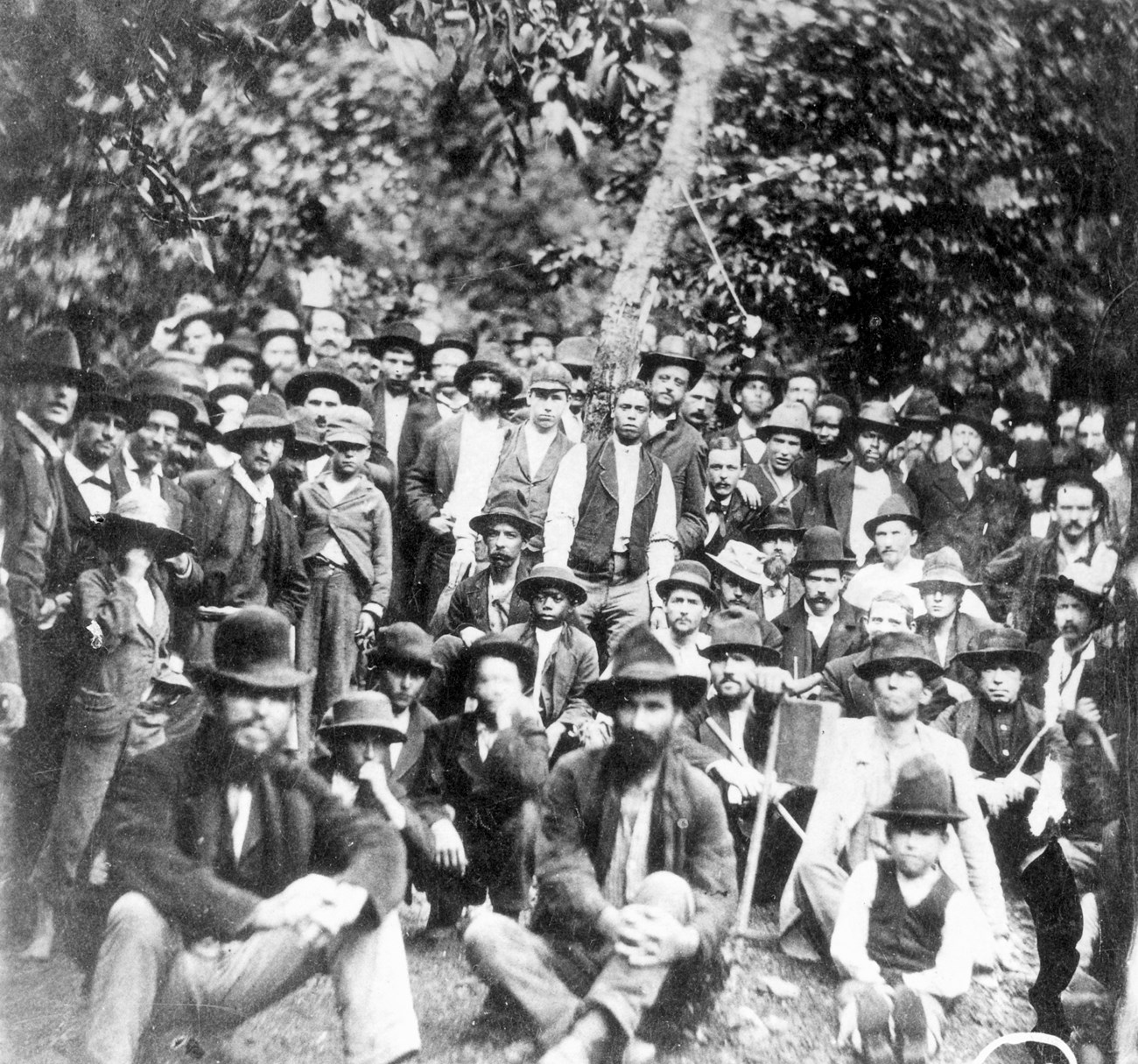

"These people embraced almost every nationality; both sexes; white and colored. They were most of them living in shanties or tents, but some of them were encamped under the trees with no other shelter. Most of them were afflicted with decease [sic] and many of them worthless and desperate characters; they were destroying the timber and shrubbery and polluting the springs." -Benjamin Kelley, 1878

Imagine you are Superintendent Kelly. What would you do to offer healing to poor people, while also protecting natural resources and private business interests?

Courtesy of the Hot Springs National Park Archive

The Challenges of a Free Bathhouse

Officially called, “Hospital Bathhouse,” or “Kelleytown,” by locals, the free bathhouse was erected on the south side of Hot Springs Mountain. Due to its location further away from the source of the thermal springs, the water had to be piped a greater distance to reach the bathhouse and was cold by the time it reached the baths. Due to the lack of hot water in the free bathhouse, Ral City patrons returned to the western slopes of Hot Springs Mountain and back to their dugout pools.

At the same time, Superintendent Kelley worked to bring order and systemic practices to the bathhouses in town. He set up regulations for bathhouses buildings, thermal water rates, and leasing services. Kelley’s goal was to transform Hot Springs Reservation into an attractive spa destination for all people.

"The Bathhouses now on the reservation are all except the (Iron Bath House) inconvenient, and very unsightly, and when the buildings on the streets are condemned, and removed, will expose these old, unsightly structures to the full view of any one passing along the street. If these old Bathhouses are permitted to remain, and no new and more elegant ones permitted to be built the growth and prosperity of this most important health giving place will be retarded beyond any reasonable estimate." -Letter from Superintendent Benjamin Kelley to Interior Secretary Carl Schurz on 2/1/1878

Left image

Aerial view of Hot Springs pre 1880

Credit: Courtesy of the Hot Springs National Park Archive

Right image

Hot Springs burned down after The Great Fire of 1878.

Credit: Courtesy of the Hot Springs National Park Archive

Solving the Access "Problem" Once and for All

After the Great Fire, bathhouse owners made every effort to bounce back; however, the appearance of Yellow Fever in Hot Springs caused panic in visitors and sent many home to ride out the epidemic. As the months dragged on, bathhouse owners grew impatient with Superintendent Kelley and his inability to solve the “Ral City problem.” They became increasingly worried that their water supply was being compromised by the people with syphilis who were using the thermal springs before the water could enter their bathhouses. For several of these establishments, paying customers were driven away by the possibility of water contamination.

Superintendent Kelley took charge of the situation by forwarding the bathhouse owners’ complaints to the Secretary of the Interior, Carl Schurz. Schurz, after reviewing the problem, ordered Kelley to remove the encampments and clear out the entirety of Ral City. Following his orders and acting within his power as Superintendent, Kelley pulled down the wooden structures, filled in all the pools, and drove people off the mountainside – which immediately infuriated the Ral City residents, locals, and visitors alike.

Courtesy of the Hot Springs National Park Archive

A Rally for Ral City

To protest Kelley’s actions, Ral City occupants and supporters held an “indignation meeting” to express their outrage and rally to rebuild the destroyed camp. Members of Ral City threatened Kelley with violence, going as far as to threaten to hang him. Former Hot Springs Mayor, T.F. Linde, traveled to Washington D.C. to deliver a petition with hundreds of signatures directly to Secretary Schurz condemning Kelley’s actions.

To Preserve Peace and Protect U.S. Property

Feeling threatened and seeing no other course of action, Kelley asked Secretary Schurz to deploy federal troops from Little Rock to put a stop to the uprising and enforce order. To counteract the adverse publicity and bolster his own position with staff at the Department of the Interior, Kelley gathered letters of support from ten prominent physicians. He sent these letters to Secretary Schurz, hoping that Schurz would send them to the Secretary of War to encourage federal troops to intervene in the insurrection on Hot Springs Mountain.

Physician observer who wrote to Secretary Schurz supporting Kelley's action:

the Ral Hole "is a bathing place for a few needy and [people with syphilis]" [...] adding that "principally it is the headquarters of a great number of thieves, tramps, jailbirds, ruffians, deadbeats and roughs. It is a nuisance for which there is no name and the sooner it is abolished, the better."

Letter from Superintendent Kelley to Secretary of Interior Schurz on September 28, 1878:

The Bath house proprietors Physicians, and Citizens have for several months urged me to abate the nuisance of the “Rhal Hole” asserting that filthy water from it polluted the water used by the Bath houses, and that it caused serious loss to them in their business as guests were afraid to bathe in or drink the water from Springs below the “Rahl Hole”. I have delayed action in this matter until now expecting it would cause some excitement. On Wednesday last I caused the structure at the Hole to be removed Thursday there were posters put up calling a meeting of all opposed to the destruction of the “Rhal Hole” at 3 O clock P.M. at that place, accordingly the mob assembled, composed of all the rable of the town including Gamblers, Roughs, Tramps led by two or three political demagogues – very inflammatory speeches were made, and outrageous resolutions were made-all tending to inflame the mob, and not only endanger the public property -but the entire town as well as the lives of peaceful citizens.

I therefore deem it my duty to ask you to confer with Gen’l Sherman and get him to order Gen’l Morrow, commanding at Little Rock to send a detachment of U. S. Troops here at once. I think the moral effect of a detachment of Blue coats will quiet all further riotous proceedings, give peace and quiet to the town and enable the civil authority to enforce the laws, and enable me to discharge my duties and protect the public property. I [have] just learn[ed] that the mob have rebuilt the Shanty over the “Rhal Hole” after being ordered to desist by the U. S. Marshall who is powerless.

After Kelley’s requests and letters were received, federal troops were deployed to Hot Springs. Captain Pratt of the Thirteenth Infantry arrived in Hot Springs on October 4th, 1878. They successfully protected the thermal springs on Hot Springs Mountain and reported no interferences or problems. They left on October 31st. At the time, the City of Hot Springs could not afford to maintain a police force, so Kelley asked that Captain Pratt’s infantry return to Hot Springs and remain in the vicinity until the Hot Springs Commission’s work was completed in 1881.

from the collection of Allan Gates

Establishing the Government Free Bathhouse

At this point, Superintendent Kelley could have easily dismissed the sick and poor who had been displaced from Ral City and absolved himself of the “problem” that they once presented. However, Kelley decided to take a proactive approach and worked with concerned citizens to build a free infirmary and bathhouse for poor people. As had been done previously, Kelley collected donations to construct the bathhouse, except this time, the building was placed on Hot Springs Mountain right above “Mud Hole Spring,” the largest of the dugout pools.

Kelley put a private individual, Marshal James Barns, in charge of running the “free” bathhouse; Barns created an honor system whereby bathers who were able to pay for baths did so and in the process subsidized baths for the poor.

On December 16, 1878, Congress passed an act stating, “That the Superintendent shall provide and maintain a sufficient number of free baths for the use of the [poor], and the expense thereof shall be defrayed out of the rentals hereinbefore provided for.” This was the first time the government institutionalized taking responsibility for bathing people who could not afford to use the private bathhouses.

Hot Springs National Park Photographic Collection

Equality Once and For All?

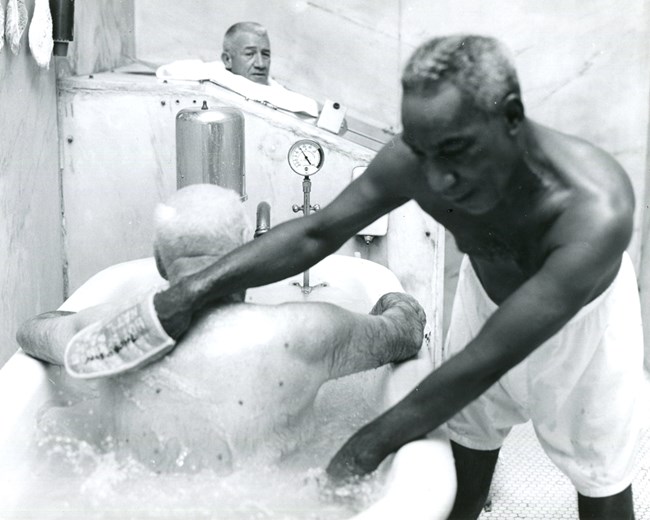

Even with access to free bathing services, the battle for equality and accessibility was far from over. In 1883, the Supreme Court overturned the 1875 Civil Rights Act which gave equal treatment to all Americans in public spaces. This decision paved the way for southern legislatures to enact “Jim Crow” segregation laws, which discriminated against Black citizens by denying them equal access to public and private facilities. The Superintendent of Hot Springs Reservation and the Bathhouse owners changed their policies to allow for racial segregation within the park, even at the Government Free Bathhouse. While Black citizens were employed in the Bathhouses, racial segregation prevented them from being able to use the bathing facilities at the same times or days as white patrons for nearly 100 years, until the Civil Rights Act of 1965 was passed.

Hot Springs National Park Photographic Collection

Ral City’s Legacy

The legacy of Superintendent Kelley and Ral City lived on through the Government Free Bathhouses. With increased demand for access to the baths, several versions of the Government Free Bathhouse were constructed throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. The last of these was called the Libbey Memorial Physical Medical Center. It offered waiting rooms, dressing rooms, private lockers, steam heat, and several large bathing pools.

In 1916, Department of the Interior established the National Park Service and Hot Springs Reservation was placed under its jurisdiction. In 1921, Congress changed the name of Hot Springs Reservation to Hot Springs National Park. The Government Free Bathhouse (Libbey) continued to provide therapeutic bathing and hydrotherapy services for poor bathers and Black citizens, who could not go to some of the other Bathhouses, until it closed on March 22, 1957.

Ral City’s legacy plays an important role in Hot Springs National Park’s history. People spoke up and fought for every citizen’s right to access the thermal spring water, ensuring that they could get the health benefits they sought, regardless of socioeconomic status. For the first time in history, Superintendent Kelley and the federal government acknowledged and took action to provide equal access to healthcare. The establishment of the Government Free Bathhouse was a major step towards equality and accessibility in Hot Springs.

What responsibility does the government have today in providing free access to the hot springs for future generations?

Sources Used

- Bathhouse owner to Secretary of Interior Carl Schurz, letter. 6 August 1878. HSNP Archives.

- Benjamin F. Kelley to Secretary of Interior Carl Schurz, letter. 12 January 1878. HSNP Archives.

- Benjamin Kelley to Carl Schurz, Secretary of the Interior, letter. 28 September 1878. HSNP Archives.

- Benjamin F. Kelley to Carl Schurz, Secretary of the Interior, letter. 10 November 1878; forwarded to the War Department "without remark," November 18. 1878. HSNP Archives.

- Captain H.C. Pratt to Assistant Adjutant General, letter. 24 October 1878. HSNP Archives.

- Clary's Celebrated Stereographic Views of Hot Springs, Ark., No. 44, "City of Siloam"; No. 46, "Pool of Siloam". HSNP Archives.

- Cockrell, Ron. The Hot Springs of Arkansas-America's First National Park. Administrative History of Hot Springs National Park, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2014.

- First and Second Reports of a Geological Reconnaissance of Arkansas, by David Dale Owen, 1860, Johnson & Yerkes, State Printers, Little Rock, Arkansas, 1860.

- Fordyce, Samuel Wesley. The Autobiography of Samuel Wesley Fordyce: Captain, First Ohio Cavalry, Army of the Cumberland: Railroad Builder, Southwestern United States. S.W. Fordyce, 1992.

- George McCray, Secretary of the War Department, to Carl Schurz, Secretary of the Interior, letter. 26 November 1878. HSNP Archives.

- Hot Springs National Park Collections, stereographs, 1860-1880s. HSNP Archives.

- H.R. 274: "An Act authorizing the Governor of the Territory of Arkansas to lease the Hot Springs in said Territory, and for other purposes"; Twenty-Second Congress of the United States, First Session, January 16, 1832 (Signed by Andrew Jackson on April 20, 1832).

- Letter from Dr. F. Harrison, October 1, 1878; letter from Charles Mathews, editor of the Sentinel, October 2, 1878; Treatise on the Hot Springs of Arkansas by Algernon S. Garnett, M.D., St. Louis, Missouri: Van Beck, Barnard and Tinsley, Printers, 1874. HSNP Archives.

- Report of J.B. Clark, Esq., to Carl Schurz, Secretary of the Interior, June 12, 1879, p. 2. HSNP Archives.

- Report of the Commission Regarding the Hot Springs Reservation in the State of Arkansas by Chief Engineer A.P. Robinson et al, Government Printing Office, Washington D. C., 1880.

- Report of the Secretary of Interior in Answer to a Resolution of the Senate relative to the Hot Springs of Arkansas, (Ex. Doc. No. 70), 1850.

- Report of the Superintendent of Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior, June 30, 1879. HSNP Archives.

- Report of the Superintendent of Hot Springs Reservation to the Secretary of the Interior. October 25, 1881. HSNP Archives.

- Shugart, Sharon. The Legacy of 'Ral City'. The Record, Garland County Historical Society, 2008.

- Statues at Large, 22nd Congress, first session, April 20, 1832, p. 505.

- Superintendent Kelley to Secretary Schurz, letter, 1 February 1878. HSNP Archives.

- Superintendent Kelley to Secretary Schurz, letter, 10 November 1878; forwarded to the War Department, November 18, 1878. HSNP Archives.

- Territorial Papers, Arkansas Territory, "Memorial to Congress by the Territorial Assembly" Approved February 15, 1820; act approved April 21, 1820 (3 Stat. 565) in pursuance of the prayer of the memorial.

- U.S. House of Representatives, Testimony Taken before the Committee on Expenditures in the Interior Department Relative to Certain Things connected with the Government property to Hot Springs, Ark. (House Ex. Doc. No. 89), 17 June 1884, p. 65.

- U.S. House of Representatives, Testimony Taken before the Committee on Expenditures in the Interior Department Relative to Certain Things connected with the Government property to Hot Springs, Ark. (House Ex. Doc. No. 89), 17 June 1884, p. 200.

- U.S. Supreme Court Reports, Rector v. United States, 92 US 698 (1875), October Term 1875.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue. La. State Univ. Pr., 1964

- W. S. Hancock, Major General, to E.D. Townsend, the adjutant General of the United States, forwarded to Carl Schurz, the Secretary of the Interior, letter. 8 October 1878. HSNP Archives.