Part of a series of articles titled On Their Shoulders: The Radical Stories of Women's Fight for the Vote.

Article

The Prequel: Women’s Suffrage Before 1848

Most suffrage histories begin in 1848, the year Elizabeth Cady Stanton convened a women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York. There, she unfurled a Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, seeking religious, educational and property rights for women – and the right to vote. While Seneca Falls remains an important marker in women’s suffrage history, in fact women had been agitating for this basic right of citizenship even before the first stirrings of revolutionary fervor in the colonies. Some, like Lydia Chapin Taft, had even voted.

On Josiah Taft’s death in 1756 at the age of 47, his wife became a wealthy widow with three minor children still at home – and the largest taxpayer in Uxbridge, Massachusetts. As the town was about to vote for a local militia to fight the French and Indian Wars, civic leaders asked Lydia to cast a vote in her husband’s place, as her funds would be critical to the war effort. Her affirmative vote on funding the local militia in 1756 was the first of three she cast as a widow. Two years later, in 1758, she voted on tax issues. In 1765, she again appeared at a town meeting to vote on school districts. Two decades before the colonies declared their independence from Britain, thirty years before the U.S. constitution was ratified, she became, according to Uxbridge Town records, America’s first recorded female voter.

Women who expressed interest in politics were rare, as it was considered unnatural. Exceptions were made, however, for some upper-class women, such as Mercy Otis Warren, who during the war years published anonymously and then used the pseudonym A Columbian Patriot in 1788 to oppose ratification of the U.S. Constitution unless it included a Bill of Rights to protect the rights of individuals from a formidable central government. She later penned a lengthy history of the Revolution under her own name. But once appeals for resistance spread through the colonies, many women asked their husbands or fathers for updates on the war. “Nothing else is talked of,” Sarah Franklin wrote her father Benjamin Franklin. “The Dutch talk of the stamp tack, the Negroes of the tamp, in short, everyone has something to say.”

As her husband John Adams set off for the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia in 1776, Abigail Adams wrote him for details of the latest battles. She also urged him, in helping to craft the colonies’ Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, to “Remember the Ladies,” warning that women would foment a rebellion “if attention is not paid” to their interests, that they would “not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.” Her husband replied, “To your extraordinary Code of Laws, I cannot but laugh … Depend upon it, we know better than to repeal our Masculine systems.”

More than any other founder, John Adams may have foreseen the waves of changes likely in the country’s electorate. “There will be no end of it,” he wrote to a Massachusetts attorney. “New claims will arise; women will demand a vote; lads from twelve to twenty-one will think their rights not enough attended to; and every man who has not a farthing [one-fourth a penny in British coin], will demand a equal voice with any other, in all acts of state (Neuman, 6).”

Before the war, most women were absent from the political scene, constrained by their duties to the home. The work was difficult –and included backbreaking duties in the fields, repeated childbirths, taxing meal preparation, and daily efforts to keep dust and dirt from invading primitive homes. Indentured servants, black and white, suffered from broken bones and pulled muscles from lugging 20-gallon containers of water from well to home, for bathing and cooking. For enslaved African-Americans, one-fifth of the nation, exhausting duties were tinged with the threat of whippings and separation from loved ones on the auction block. But once the war began, women heard the call. All over the colonies, effective boycotts against British products required a buy-in from women. And buy in they did. Women founded anti-tea leagues, meeting to brew concoctions of raspberry, sage, and birch to substitute their herbal mixes for well-regarded English teas. Others shared camaraderie in collective gatherings to weave material from local products. Hundreds of spectators came to watch. Young women reveled in the task, feeling they were making a contribution to the nation’s future. One girl at the spinning parties wrote that she “felt Nationaly,” part of “a fighting army of amazones ... armed with spinning wheels.”

In New Jersey, lawmakers heard the call too, and adopted a state constitution on July 2, 1776 that offered the vote to “all inhabitants of this colony of full age, who are worth £50.” The new vote for women applied to only a small proportion of the female population. Coverture laws meant women could not own property unless they were single or widowed, like Lydia Taft. Married women gave up rights to own property, which transferred to their husbands. No one knows how many single or widowed women of 21 years or older in New Jersey had amassed £50 worth in holdings by 1776. Pamphleteer William Griffith, who said he found it “perfectly disgusting” to watch women cast ballots, estimated the number at 10,000 or more (Neuman, 11).

Despite all these early, significant steps towards women’s enfranchisement, the guiding rule of suffrage history is that male politicians never cede power unless it advantages them. John Condict, a Republican congressman angered by the votes of 75 Federalist women against him, launched a successful campaign to rescind women’s rights in 1807. Legislators did not rewrite the constitution, they merely passed a new election law limiting the vote to white male taxpayers. What historian Rosemary Zagarri dubbed “a revolutionary backlash,” when men reclaimed the power of politics, had begun.

If women lost voting rights after the Revolution, one new role was added – what historian Linda Kerber called the Republican Motherhood. Asked to educate the next generation of patriots in the new republic, they pressed this advantage to win new opportunities in education. Advertisements soon appeared for female academies that would, like the one opened by Judith Sargent Murray in Dorchester, Massachusetts, teach “Reading, English, Grammar, Writing, Arithmetic, the French language, Geography, including the use of Globes, needle work in all its branches, painting and hair work upon ivory.” And once armed with knowledge, women in great numbers entered the political sphere even before they won the vote. In petitions often sent through stealth networks of like-minded women, many women fought against President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Policy. They lost, and Native Americans were banished from their homelands to Oklahoma in a naked land grab, which killed many in what historians now call the Long Trail of Tears. In the 1830s, many women demanded an end to slavery and aided the Underground Railroad that helped thousands escape slavery. These nascent acts of politics, cast amid the Second Great Awakening, an evangelical movement that urged Christians to atone for their own sins and that of their nation, set the stage for a wider appeal for the vote in the 1840s.

The first to make the case for abolition were the Grimke sisters. Born into a slave-owning family in Charleston, South Carolina, Angelina Grimke and her older sister Sarah were eager to give witness to the daily humiliations of slavery. They had fled the South to testify to its cruelties. In a letter to abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison published in his newspaper, Liberator, Angelina wrote, “It is my deep, solemn, deliberate conviction that this is a cause worth dying for.” In speaking for the slave, the Grimke sisters were regularly assailed for speaking in public at all, as this was a privilege restricted to men. In her Appeal to the Christian Women of the South in 1836, Angelina urged women to lobby their legislators on the issue, “as a matter of morals and religion, not of expedience or politics (Grimke, 26).”

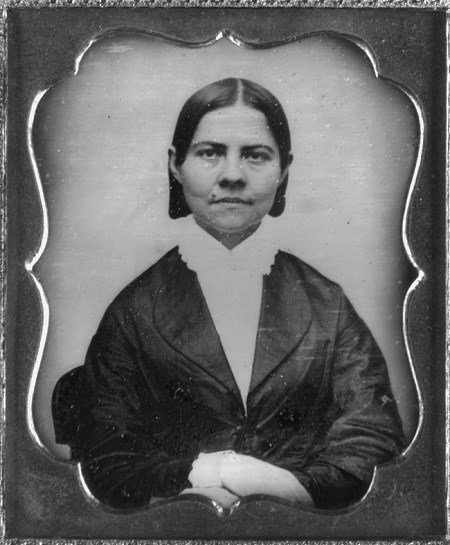

Perhaps the greatest spur to female advocacy against slavery and for women’s suffrage was Lucy Stone, one of the first female graduates of Oberlin College. In the summer of 1847, Stone began lecturing for the Anti-Slavery Society. The sight of a woman speaking in public provoked much anger by men in the audience, who pelted the stage with prayer books, rotten fruit and sometimes on a winter’s day, cold water. Once in Cape Cod, an angry crowd stormed the stage. Stone asked one of the attackers to escort her outside. The man not only ushered her to safety, he stood guard as she climbed a tree stump and continued to lecture. In a report, the Anti-Slavery Society said she had been “of very high value,” attributing her popularity to the “thoroughness of preparation … and the gentleness of demeanor.”

Samuel May, secretary for the society, soon protested her mingling of the two causes. “The people came to hear anti-slavery, and not woman’s rights; and it isn’t right,” he said. To this Stone replied, “I was a woman before I was an abolitionist” (Willard, p. 694). They agreed that she would receive a reduced fee – from $6 to $4 a week – for lectures on Saturdays and Sundays to advance the cause of the slave. On weekdays, when fewer came to hear lectures, she would speak about equality for women, the first to make a living as a lecturer for women’s rights. Frederick Douglass, the famed abolitionist orator, was also a lifelong suffragist. Late in life he commented on the mingling of the two causes. “When I ran away from slavery, it was for myself; when I advocated emancipation, it was for my people; but when I stood up for the rights of women, self was out of the question, and I found a little nobility in the act.”

After the Civil War, the two sides would come to blows over their shared priorities – Douglass, Lucy Stone and other abolitionists supporting the 14th and 15th Amendments that granted voting rights to black adult men, while Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony campaigned actively against them, arguing that African American men should not win the vote if women couldn’t also claim their rights to citizenship. This schism would splinter the women’s suffrage cause for several decades. Even today, historians still debate whether this untethering of women’s suffrage from abolitionism set back the cause of women’s rights or propelled it forward in an autonomous path of its own. But first, in this prequel to activism, women fought to acquire skills of the public sphere, to gain knowledge of the rules that guided politics. As Lucy Stone put it, first they had to learn “to stand and speak.” They would showcase that knowledge in the conference in Seneca Falls, where Stanton’s declaration that women should be eligible to vote was so controversial that her co-sponsor, Quaker Lucretia Mott, told her, “Why Lizzie, thee will make us ridiculous” (McMillen, 93).

Author Biography

Johanna Neuman is an award-winning historian and author of two books on the triumphant campaign by women to win the vote. As a journalist, she covered the White House, State Department and Congress for USA Today and the Los Angeles Times. Johanna won a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard University and holds a PhD in history from American University. She currently lives in Florida and has dedicated the rest of her career to writing books about the history of women through archival research, storytelling, and journalist skills. Her first book as a historian was Gilded Suffragists: The New York Socialites Who Fought for Women’s Right to Vote (2017) followed by How Women Won the Vote: The Long History (2020).

Bibliography

“1776 State Constitution,” State of New Jersey, Department of State, accessed March 13, 2020.

“Declaration of Sentiments,” National Park Service, last updated February 26, 2015.

“Frederick Douglass on Woman Suffrage,” BlackPast, January 28, 2007.

Grimke, Angelina Emily. Appeal to the Christian Women of the South, American Anti-Slavery Society, 1836.

“Grimke Sisters,” National Park Service, last updated February 26, 2015.

“Letter from Abigail Adams to John Adams, March 31, 1776,” Adams Family Papers Archive, Massachusetts Historical Society, accessed 13 March 2020.

“Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, April 14, 1776,” Adams Family Papers Archive, Massachusetts Historical Society, accessed 13 March 2020.

“Lydia Chapin Taft – New England’s First Woman Voter,” New England Historical Society, accessed March 13, 2020.

McMillan, Sally Gregory. Lucy Stone: An Unapologetic Life, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2015.

McMillen, Sally. Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women's Rights Movement. NewYork, NY: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Michals, Debra. “Lucy Stone, 1818-1893,” National Women’s History Museum, 2017.

Michals, Debra. “Mercy Otis Warren, 1728-1814,” National Women’s History Museum, 2015.

Neuman, Johanna. And Yet They Persisted: How American Women Won the Right to Vote. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2020.

Purcell, Sarah J. An Eyewitness History: The Early National Period. New York, NY: Facts On File, Inc., 2004.

“Republican Motherhood,” Wikipedia, accessed March 13, 2020.

Rowan, Diana Newell, “How the Revolution helped liberate women,” review of Liberty's Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750-1800, by Mary Beth Norton, Christian Science Monitor, July 9, 1980.

“The Women of the American Revolution/Sarah Franklin Bache,” Wikipedia, accessed March 13, 2020.

“Trail of Tears,” Museum of the Cherokee Indian, accessed March 13, 2020.

Willard, Frances E. and Mary A. Livermore, eds. A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life, Buffalo, NY: 1893.

Zagarri, Rosemarie. Revolutionary Backlash:Women and Politics in the Early American Republic, Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020.

Tags

- belmont-paul women's equality national monument

- independence national historical park

- trail of tears national historic trail

- women's rights national historical park

- women's history

- revolutionary war

- political history

- african american history

- new york

- pennsylvania

- massachusetts

- new jersey

- suffrage

- native american history

- american indian history

- religious history

- abolition

- underground railroad

Last updated: September 11, 2025