Part of a series of articles titled Women's History to Teach Year-Round.

Article

(H)our History Lesson: The First Steps of Desegregation, Rev. Dr. Cynthia Lewis Gaines Remembers

Introduction:

"Women's History to Teach Year-Round" provides manageable, interesting lessons that showcase women’s stories behind important historic sites. In this lesson, students explore school integration through the experience of Cynthia Lewis Gaines, one of the first Black students to integrate an all-white high school in New Kent County, Virginia.

This lesson was adapted by Talia Brenner and Katie McCarthy from the Teaching with Historic Places lesson plan, “New Kent School and the George W. Watkins School: From Freedom of Choice to Integration.” For more information about this topic, explore the full lesson plan.

Grade Level Adapted For:

This lesson is intended for middle school learners, but can easily be adapted for use by learners of all ages.

Lesson Objectives:

Learners will be able to...

-

Understand how different communities approach school integration and how it affected students.

-

Describe the role of activism at the local level.

-

Identify aspects of a text that reveal an author’s point of view or purpose.

-

Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source.

Inquiry Question:

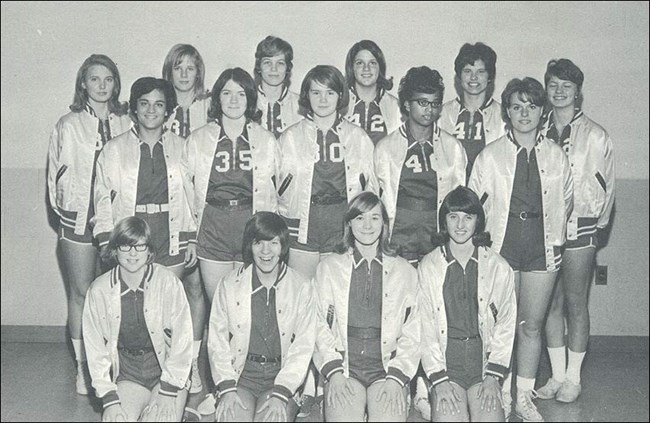

What do you think is happening in this photo? How do you think the students pictured feel? How do photos like these help us understand the desegregation of public schools?

Background:

Ten years after the Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education (1954), most white government authorities in the South continued to segregate public schools. Many African-American schools had excellent teachers and administrators. However, the schools still suffered from inadequate resources, such as crumbling buildings, battered books, and insufficient funds for after-school programs.

It was at this time that Dr. Calvin C. Green filed a lawsuit against the local school board. Green was the president of the New Kent County, Virginia branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and a father of three. Feeling pressure from the lawsuit and the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the New Kent County school board unveiled the "freedom-of-choice" plan. They claimed this plan would address school segregation. Under "freedom-of-choice," African-American students would continue at the African-American school, and white students would continue at the white school. However, African-American students could petition to attend the white school.

Unsurprisingly, the "freedom-of-choice" plan did not significantly affect racial segregation in the county's two public schools. Only a few Black students transferred from the all-Black George W. Watson School to the otherwise all-white New Kent School. No white students transferred to the George W. Watkins School.

Document: An Interview with Rev. Dr. Cynthia Lewis Gaines

Cynthia Lewis was one of the first students to integrate the New Kent School under the “freedom of choice” plan. She had previously attended the George W. Watkins School. As a teenager at the New Kent School, she was one of very few Black students in a school that had never experienced racial diversity. As an adult, Cynthia, then Rev. Dr. Cynthia Lewis Gaines, worked as a school principal in Richmond, Virginia. Following her retirement, she served on the New Kent County School Board. This interview was conducted by Brian Daugherity and Jody Allen on November 13, 2001 in Dr. Gaines' office at William Fox Model Elementary School in Richmond.

Topic: First day at New Kent School

Well, [sigh] the school, the inside of the school is a little bit different now than it was when I actually went there. When I went there, you came in the front door and there was an auditorium and a walkway all the way around that auditorium. It was customary that kids came in the building and stood all around that auditorium until the bell rang. Which meant that my first day there I had to walk through all the kids who were standing there staring at me. So, there was a little name-calling, a little laughing, all those kinds of things going on as we walked through. I felt strange walking in because it was all new, but I wasn't afraid to walk in there.

Question: What other types of experiences did you have at New Kent School that first year?

Well, I remember being in classes and I always tried to sit on the first row or second row, and I would just be in class and I'd go like this [runs her hand through her hair] and the back of my head was just full of spit balls that the kids behind me were blowing in my head. They would chew the paper up real tiny and blow it through the little Bic ink pens, so you wouldn't really feel it, but when you stuck your hand in your head you felt it.

When we first got there, if we came out of the cafeteria line and sat at a table the entire table would get up. So, after about two days of that I said, "you know what? We are going to the cafeteria today and everybody's going to sit at a different table and we are going to clear 11 tables" (there were 11 Black high school students that year). They [her friends] were like all right, let's do it. So we go in, each one comes out of line and we sit at a different table. We cleared 11 tables, kids standing all around the walls with their trays in their hands just eating and we're just laughing because after a while we had to make it funny. If we didn't make it funny, we couldn't have made it [pounds hand on table with each word]. So we just found ways to make it funny.

At the high school, there was really no attempt by the students or teachers to make us fit in, so we were charged with making ourselves fit in. So I'll give you an example: the first year I was there I tried out for the girls basketball team, and I was the first black girl to ever play basketball for New Kent. But at that time the varsity team, the cheerleaders, and the girls team all rode on the same bus because we didn't have JV [Junior Varsity] girls way back then. But no one would sit by me on the bus the entire basketball season; I don't care if we went to Matthews, Middlesex, Yorktown, for miles no one would sit by me on the bus. And they would sometimes sit three in a seat to keep from sitting by me on the bus, so after a while you just had to make things funny so you wouldn't be hurt. So I would cross my legs, stretch out on the seat put my suitcase up, and prop my feet up and just ride.

And there were girls on the team that did not mind passing me the ball because they knew I could play, so I would pass them the ball. If I got out there and it was somebody who had been mean to me, and I mean I was a child, I know that's not right now, but.... [laughter] I wouldn't pass them the ball. I didn't care if we missed the basket or the points, I wouldn't do it.

And I remember my first basketball game. My parents could not attend and they said "but you go ahead. You'll be all right because it's at a school." Actually it was a private school, and it was a Catholic school, so you're going to be all right. I went to that game and I was the only black person in the gym. And I saw the janitor come by and look in there because he, I guess, wondered where I came from. When they did the starting line up, 'cause I was in the starting line up, and back then there were six girls on the team, just like guys had six, and so they did the starting line up, and I was the last person they called. This man who was up there in the stands, he stood up--and you know how it's quiet because you've just done the Star-Spangled Banner and then they introduce the team--so it's kind of quiet and they had clapped and then they called my name. And this parent stood up and said, "Oh my God, five white girls and one African," and the entire gym just broke into laughter and there I was on the floor in the eighth grade.

Question: What were your classes like?

I won't say that the courses were more challenging because we had good teachers at the black school. Their [New Kent School] tests; there were more items. Like the first test I had in eighth grade in my world geography test, or whatever it was, had 150 questions on it, which was something I had not seen. But now, that could have just been the difference between seventh and eighth grade. I don't know what the kids in eighth grade would have had at Watkins [George W. Watkins School].

Question: How did the schools compare?

We actually had more courses [at the New Kent School]. For example, we had Latin, we had Spanish, and we had French. Well, see, the Black school had one language. The science class at the Black school only had three microscopes, but yet, at the white school there was a microscope for two children to sit and share. But we only had three and we only had two sinks in that science class. We also had used textbooks. The furniture was not as nice. We had good teachers and good people [at George W. Watkins].

Question: Were there any white teachers who interacted favorably with you?

Sure. Mr. Galloway, Mr. Chapman, Rev. Stansfield, Mrs. Thomas

Question: Did you ever become friends with any of the white students?

Once they got to know us. By my sophomore year, we actually had friends, black and white friends.

Question: How did the community respond to the lawsuit?

There was opposition also from blacks as well as from whites. There were parents and kids who thought we shouldn't go down there. There were teachers at the school who thought we shouldn't go there. There were teachers and students who were very angry with us because in the end, they lost their school.

Epilogue

New Kent County continued its "freedom of choice" plan for several years. Dr. Green’s case went all the way up to the United States Supreme Court. Finally, in 1968, the Supreme Court decided in Charles C. Green, et al., v. County School Board of New Kent County, Virginia, et al. that the “freedom of choice” plan was not enough and that the school board had to actually integrate its public schools.

By more forcefully requiring racial integration, the decision affected school systems throughout the United States. In New Kent County the school board responded to the decision by pooling all the county’s high school students in the now integrated New Kent School, renamed New Kent High School. In the 1969-1970 school year, all New Kent County public high school students attended a racially integrated school for the first time.

Yet the issue of school segregation is not gone. Since the 1980s, the number of U.S. public schools with racially homogenous populations has increased. Activists today also point to many other racial disparities in the public school system.

Discussion Questions

-

Re-read the section of Cynthia’s narrative where she talks about how the girls on her basketball team treated her. Then observe the picture of the basketball team. How do you think she felt to be posing in the picture with her team?

-

According to Cynthia, in what ways did the white students at the New Kent School mistreat the African-American students? What techniques did she use to cope?

-

Cynthia said that by her sophomore year, the third year she spent at the school, there were some friendships between African-American and white students. Why do you think that these friendships eventually developed? Do you think that the changes inside the school system (limited desegregation) or outside the school system (the Civil Rights Movement in the late 1960s) helped more in forming these friendships?

-

Dr. Gaines later served as a school principal and on the New Kent County School Board. How do you think that her experiences as a student might have affected the way she governed?

-

Did anything from Cynthia’s account surprise you?

-

What can you earn from personal accounts that you can’t find in a textbook?

Activity: History of My School

Segregation was a national problem, and communities across the U.S. were affected by the Civil Rights Movement and the fight over desegregation. At the same time, local, regional, and state factors greatly influenced communities' experiences with desegregation.

Have learners use newspapers, yearbooks, and other primary materials to research the history of their school or a school in their community from 1954-1970 (essentially from the Brown Supreme Court decision through the implementation of the Green Supreme Court decision).

As they research, learners should pay attention to the following questions:

-

Was the school racially segregated at the beginning of this time period? If so, was it integrated during this time period? What evidence have you found that shows this?

-

What are the similarities and differences between this school and the schools in New Kent County? What factors might account for these similarities or differences?

-

What are the racial demographics of the school today, as compared to other schools nearby (private or public)? Would you say that the school is racially integrated?

Wrap-up:

-

Have you ever gone through something scary or challenging? How did you feel? What motivated you to continue?

-

Why is Cynthia’s story important on the local and national level?

-

What does learning about Cynthia’s story make you curious about?

-

Are there legacies of segregation in your school or community?

Additional Resources:

University of Virginia: Civil Rights in U.S. and Virginia History

This website from 2004 stems from a course at the University of Virginia that covers segregation and the Civil Rights Movement in a local and national context. The website offers a wealth of documents, images, and sources, including the Virginia Interposition Resolution of 1956, images from the Davis case, and much more.

Virginia Commonwealth University: Photographs of Black and White Schools, Prince Edward County, Virginia--1961-1963

These images, by Dr. Edward H. Peeples, of the schools in Prince Edward County illustrate the differences between the resources that the county provided for its black students compared to its white students. According to Peeples' research, in 1951 all but one of the 15 black school buildings were wooden frame structures with no indoor toilet facilities, and had either wood, coal, or kerosene stoves for heat (one additional brick school building was built for blacks in 1953).

National Park Service

Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site is a unit of the National Park System. The site is located at Monroe Elementary School in Topeka, Kansas. Monroe was the segregated school attended by the lead plaintiff's daughter, Linda Brown, when Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was initially filed in 1951. The park's Web page provides in-depth information on the case as well as related cases, and visitation and research information.

The National Register of Historic Places' on-line travel itinerary, We Shall Overcome provides information on many places (in states across the U.S.) listed in the National Register for their association with the modern civil rights movement, including both the George W. Watkins School and the New Kent School.

In 1998, Congress authorized the National Park Service to prepare a National Historic Landmarks Theme Study on the history of racial desegregation in public education. The purpose of the study is to identify historic places that best exemplify and illustrate the historical movement to provide for a racially nondiscriminatory education. This movement is defined and shaped by constitutional law that first authorized public school segregation and later authorized desegregation. Properties identified in this theme study are associated with events that both led to and followed these judicial decisions. Both the George W. Watkins School and the New Kent School were identified and later designated as National Historic Landmarks.

Tags

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- virginia

- virginia history

- women's history

- african american history

- art and education

- civil rights

- civics

- late 20th century

- segregated schools

- desegregation

- desegregation of public education

- hour history lessons

- educational activity

- women and education

- twhplp

- crbp aah

Last updated: May 9, 2023