Last updated: December 6, 2020

Article

Silent Sentinels of Kiska

Official U.S. Navy Photograph, National Archives, 80-G-19942.

Kiska in World War II History

On 7 December 1941 the Empire of Japan carried out a surprise aircraft carrier strike on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor. At the outbreak of the War, Japan controlled all of Micronesia with the exception of Guam and Wake Islands, both of which were U.S. possessions. Rapid advances by Japanese Army and Navy forces saw the occupation of large sections of the Western Pacific.

U.S. counterstrikes on Japanese installations in the Pacific highlighted to the Japanese shortcomings in their defensive strategies. Hitting closer to home was the Doolittle raid of 18 April 1942, when carrier-launched B-25 medium-range bombers attacked Tokyo and other Japanese centers. The raid served several purposes, and while the actual damage was low, the attack reinforced Japan’s interest to capture Midway with plans to invade the Aleutians.

The complete Japanese strategic objective for occupying the western Aleutian Islands continues to be researched and debated by historians and scholars – with views that include seeing the invasion as a diversionary action from attacking at Midway, expanding and establishing Japan’s defensive perimeter, and disrupting U.S. and U.S.S.R. communications.

In a dual operation, Japanese forces moved to attack both the Aleutians and Midway. On the 3rd and 4th of June 1942, a Japanese carrier strike force attacked the U.S. military bases at Dutch Harbor, inflicting minor physical, but considerable psychological damage. The War had come to Alaska and the Aleutian Islands Campaign had begun.

In a simultaneous move, a Japanese aircraft carrier strike force attacked Midway. Because U.S. intelligence had been able to break the Japanese code, U.S. carriers lay in wait. In the ensuing naval battle (4-7 June), the Japanese lost all four carriers, while the U.S. Navy lost only one. As a result of the defeat, the planned Japanese amphibious assault on Midway was abandoned.

Despite the defeat at Midway, Vice-Admiral Hosogaya, Commander of the Japanese Fifth Fleet and in charge of the Aleutians operation, argued that the Aleutian landings be carried out to occupy the area and prevent U.S. advances down the Aleutian Chain towards Japan. Kiska was to be occupied until autumn. That plan was later amended to allow for a prolonged occupation. Japanese Naval forces occupied Kiska on 6 June and a day later Japanese Army troops landed on Attu.

Due to faulty intelligence the Japanese carriers attacking Dutch Harbor were unaware of the U.S. air bases at nearby Cold Bay and Umnak. Untouched by Japanese attacks, these bases proved crucial in the first days of U.S. response which was quick with bombing runs. Attempts to dislodge the Japanese from getting a foothold, however, failed, and soon became a “routine” of base development and U.S. bombing runs that was to last nearly fourteen months.

Weekly Pictorial Report, “Detailed News of Aleutian Attack,” no. 228, July 8, 1942, pp. 3-5.

Events on Kiska 1942-1943

For the first few months of the war, the 10-man U.S. weather personnel were the only presence on Kiska. That changed dramatically on the morning of 6 June 1942 when some 550 Japanese marines landed on Kiska. While Attu was occupied by Japanese Army personnel on the following day, a navy garrison and a construction battalion were landed on Kiska and immediately began developing Kiska Harbor into an effective base with the seaplane facilities on the northern side, and a midget submarine base at Trout Lagoon.

The first gun batteries erected to protect the fledgling base, included the 75mm anti-aircraft battery in the valley behind the main Japanese encampment, the 4.7-inch coastal defense gun battery on North Head, and a 13.2mm anti-aircraft battery on a rise next to the encampment.

On 1 July the garrison was reinforced with 1,200 naval troops and a large quantity of war material, including additional gun batteries, which had been intended for the occupation of Midway. In September, Army troops, who had initially occupied neighboring Attu, were stationed on Kiska to protect Gertrude Cove, and were augmented by further Army troops in November. At the height of base development, the Kiska garrison comprised over 6,800 personnel.

The fierce Aleutian weather took its toll on the Japanese who, in the absence of docks, had to ferry ashore all supplies using small landing craft and barges and who lost several sea-plane fighters due to strong surf. Having started late and without heavy equipment, the Japanese never completed their airfield on North Head.

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, RG-111-SC-182173

Japanese Base Development

With the Navy at the harbor and the Army to the south at Gertrude Cove, the Japanese force set to work developing the Kiska base by digging in, literally, to create a series of tunnels for underground air raid shelters, hospitals, and storage rooms. Besides the gun emplacements, the base included machine shops, power stations, a saw mill, as well as water systems complete with fire hydrants.

There were Shinto shrines and gardens. A network of roads and telephone lines connected the barracks with the various defense installations. Above ground buildings were surrounded by thick sod walls that served as blast walls and as protection against the incessant wind. Today, these high walls are still standing.

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, RG-80-CF-7825-69034C-Detail

The Japanese Defense Strategy

All key assets of the Japanese presence on Kiska, the submarine base and the sea-plane base, were located in Kiska Harbor. Thus the Japanese defense strategy included:

- denying the U.S. forces an opportunity of a direct assault by establishing a system of medium-range coastal defense gun batteries with overlapping fields of fire;

- establishing a stratified network of anti-aircraft gun batteries, capable of repelling U.S. bombers at various altitudes;

- establishing an effective air cover, using floatplane fighters to intercept approaching bombers and using medium range observation floatplanes for reconnaissance; and

- denying the U.S. forces the opportunity of landing at Gertrude Cove, by placing a Japanese Army garrison there, along with various anti-aircraft batteries and two tanks.

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, RG342FH-3A-29657.

The U.S. Response

The U.S. response to the Japanese landings on Kiska was swift. The “Kiska Blitz” began on 11 June 1942, when the U.S. Army Air Forces long range B-24 and B-17 bombers flew missions from Umnak along with the U.S. Navy PBYs flying out of Atka. Initial losses were high due to Japanese anti-aircraft fire, the rough weather, and later by the Japanese Rufe floatplane fighters.

Once airbases had been built closer to Kiska, at Adak and Amchitka, fighters (including P-38, P-39 and P-40s) escorted the bombers, engaging with a dwindling number of Japanese aircraft and subduing any anti-aircraft fire through low-level strafing runs.

The U.S. forces, primarily the Eleventh Air Force, flew numerous missions again Kiska for over a year, dropping more than 6 million pounds of bombs. While the accuracy and effectiveness of the bombing against targets other than shipping was limited, it disrupted the Japanese transportation of supplies as well as base construction.

Following the U.S. landings on Attu on 11 May 1943 and the subsequent annihilation of the Attu garrison, it became clear to the Imperial Japanese Headquarters that Kiska could not be defended. With Attu in American hands, Kiska could only be resupplied by submarine. U.S. invasion appeared imminent as the bombing of Kiska intensified.

Rather than requiring the Kiska Garrison to make a futile final stand, as had been the case on Attu, Tokyo decided to evacuate the entire garrison, first by submarines and finally, on 28 July 1943 by sending a surface fleet. In an unprecedented maneuver, over 5,100 troops embarked in less than an hour, and slipped away, undetected.

When U.S. and Canadian forces finally landed on Kiska in mid-August, they found the island devoid of Japanese. Yet, confusion in the fog and inexperience resulted in over 100 casualties from friendly fire. The U.S. and Canadians went to work setting up a base. At first, tent cities sprung up among the debris of the Japanese occupation, but once a proper pier had been built, construction supplies were landed and a formal base established, complete with officer’s mess and movie theater. The military maintained a presence on Kiska through the end of the war in 1945.

During this time, guns were inventoried, with all of the small guns being removed or souvenired by the soldiers. Some of the larger guns were taken off the island for in-depth performance testing by U.S. intelligence.

The Kiska Battlefield: Then and Now

Construction activities by the Japanese, and later by the U.S. and Canadian forces, combined with the effects of the U.S. bombing, have turned the central part of Kiska into a unique cultural landscape—a battlefield pure and simple with no later additions or changes in land use.

Evidence of war is ever present, ranging from roads and the revetments for barracks and tents, to bomb craters, major pieces of military equipment, and the distinctive Japanese guns.

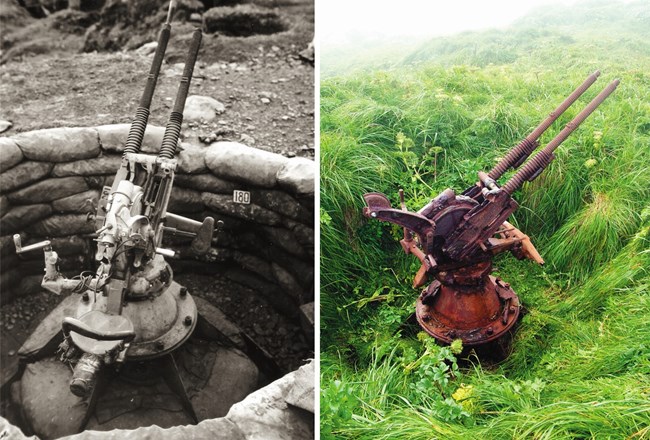

Left: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, RG-80-CF-53135

Right: NPS/Dirk HR Spennemann

The Guns

13.2mm Anti-Aircraft Guns

The mainstay of the Japanese light anti-aircraft defense was the 13.2mm Type 93 heavy machine gun. Introduced in 1933, it was produced in very large quantities until the end of the war. The most common type was a twin-barrel configuration, placed on four outriggers, which could be easily re-sited as the tactical need arose.

Despite a practical rate of fire of 250 rounds per minute, the weapon was only effective against low-flying aircraft as it had an effective height of only 3,500 feet, where hits could be expected. Yet, with the gunner seated astride the breech in a reclining position, the weapon could be rapidly moved, allowing to follow approaching and departing targets. Many attacking U.S. aircraft returned to their bases badly shot up by the 13.2mm and the heavier 25mm anti-aircraft guns. This forced the U.S. forces to abandon low-level attacks until their bombers could be accompanied by fighter planes, which could subdue the anti-aircraft fire with strafing runs.

13.2mm Anti-Aircraft Guns Today

Many of the 13.2mm gun mounts are missing one or both of the barrels. While some seem to have been taken by the evacuating Japanese soldiers (and probably dropped into the harbor), others were most certainly souvenired by U.S. and Canadian troops after their unopposed landing on Kiska.

Left: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, RG-80-G-80283.

Right: NPS/Dirk HR Spennemann

25mm (Type 96) Anti-Aircraft Guns

The mainstay of Japanese light anti-aircraft defense was the 25mm automatic cannon. Although developed as a ship-based fast firing gun, the Type 96 cannon found widespread use at Japanese Navy shore installations throughout the Pacific theatre of war. Capable of sustaining a rate of 220 rounds per minute, these twin-barrelled weapons proved very versatile against both aerial and land targets.

It was a very effective weapon against aircraft flying below 6,000 feet. Four 25mm batteries protected the approaches to the Main Japanese Camp Area in the northern sector of Kiska Harbor.

25mm (Type 96) Anti-Aircraft Guns Today

After the reoccupation of Kiska, Allied intelligence staff removed several 25mm guns for performance testing and readied others for shipment as war trophies. Kiska represented the first opportunity to have a good look at one of the most advanced Japanese medium anti-aircraft weapons.

Today only one 25mm battery remains in its original place. Standing silent sentry on Mercy Point, the guns overlook Kiska Harbor. Because of their complex design, the twin-barelled guns suffer greatly from accelerated corrosion.

75mm (Type 88) Anti-Aircraft Guns

The mainstay of Japanese heavy anti-aircraft defense was the 75mm Type 88 guns, extensively used by both the Japanese Navy and Army throughout the South-East Asian and Pacific theatres of war.

Capable of a rate of fire of 20 rounds per minute, these manually operated guns fired both high explosive and time-fuzed shells with an effective ceiling of 22,000 feet. Batteries of four guns each covered the main approaches to Kiska Harbor, being sited on South Head, North Head, just above the main camp and in central northern Kiska. Two additional batteries protected the Army garrison at Gertrude Cove.

The guns were supported by five outriggers which could be rapidly collapsed to a one-axle trailer for rapid re-siting. Indeed, on neighboring Attu the Japanese defenders used these 75mm guns very effectively in combat against U.S. ground soldiers.

75mm Anti-Aircraft Guns Today

While the 75mm Type 88 anti-aircraft guns are ubiquitous on Kiska, all of them have been heavily stripped of significant gun control components by souveniring soldiers and subsequent visitors.

The guns at Kiska Harbor are still in their original positions. Many of the barrels still point skyward, evocative of the struggle between the attacking U.S. airmen and the Japanese defenders.

The most remarkable of all is a gun on South Head, which is still on its tires. It was shifted by the Japanese in the last days of their presence on Kiska and never formally made operational again.

NPS Sam Maloof WWII in Alaska Photograph Collection, no. 043024, courtesy Beverly Maloof.

12cm Dual Purpose Guns

Primarily designed as heavy anti-aircraft weapons for Japanese warships, the 12cm dual purpose guns entered service in 1935. Capable of firing 12 rounds per minute, the gun was effective up to 22,900 feet. The thin skinned turret shields only protected the guns from the elements, but not from enemy action.

The four-gun battery on North Head was the heaviest anti-aicrcraft the Japanese emplaced on the island. The guns had been destined for Midway Atoll but were re-routed to Kiska when the planned invasion had to be abandoned. One of the four guns was destroyed by U.S. bombing after the Japanese had evacuated the island.

12cm Dual Purpose Guns Today

The capture of four such guns on Kiska was a significant windfall for U.S. intelligence. Because the 12cm dual purpose gun was installed on many modern Japanese warships, U.S. forces shipped one of the four guns for testing back to the U.S. mainland. Likewise, the study of the damaged gun (in situ, below left) allowed U.S. intelligence to assess the vulnerability of such guns to aerial attacks. Today the thin metal of the turret shield is corroding fast. The skeleton of the bomb-ravaged gun is a dramatic reminder of the destructive realities of war.

4.7-inch Coastal Defense Guns

The battery of four 4.7-inch guns was unloaded the day after the Japanese landings on Kiska. Dragged with manual labor into position on the north-eastern tip of North Head, the battery was operational for manual fire less than four weeks later. The battery’s field of fire controlled all possible landing beaches on the northeastern side of Kiska.

The battery was comprised of two British naval guns and two Japanese copies, all built prior to World War I. With an effective range of only four miles, these guns had long been obsolete as naval armament but proved very capable weapons to deter possible landing operations. The battery had range finding and fire control positions in the rear and was flanked by two powerful searchlights.

Despite concerted U.S. bombing efforts, these guns remained operational throughout the Japanese occupation of Kiska. Only after the Japanese had evacuated the island did U.S. bombers manage to damage one of the guns.

4.7-inch Coastal Defense Guns Today

Even though long obsolete as naval weapons, these vintage guns were used by the Japanese in a coastal defense role as well as armament on cargo vessels. Thus U.S. intelligence removed one of the Japanese-built guns and shipped it to the U.S. mainland for evaluation.

Even though the remaining three guns have been stripped of most of the smaller components, they are illustrative of Japanese coastal defense on Kiska.

6-Inch Coastal Defense Guns

The heaviest guns on Kiska were the pre-World War I vintage 6-inch naval guns of British and Japanese manufacture. Sited on North Head and on Little Kiska, two coastal defense batteries of three guns each guarded the entrance to Kiska Harbor. With an effective range of three miles, the guns would have been suitable to repel enemy landings, but proved quite ineffective when U.S. cruisers shelled the island on 8 August 1942.

6-Inch Coastal Defense Guns Today

Today, the guns on Little Kiska are in an excellent state of preservation and provide a visually striking reminder of the Japanese defense intentions.

Two of the guns on North Head, both of Japanese manufacture, were removed for testing by U.S. intelligence. The remaining gun, severely damaged by U.S. bombing after the Japanese had evacuated the island, is half buried under soil due to the construction of U.S. barracks close-by.

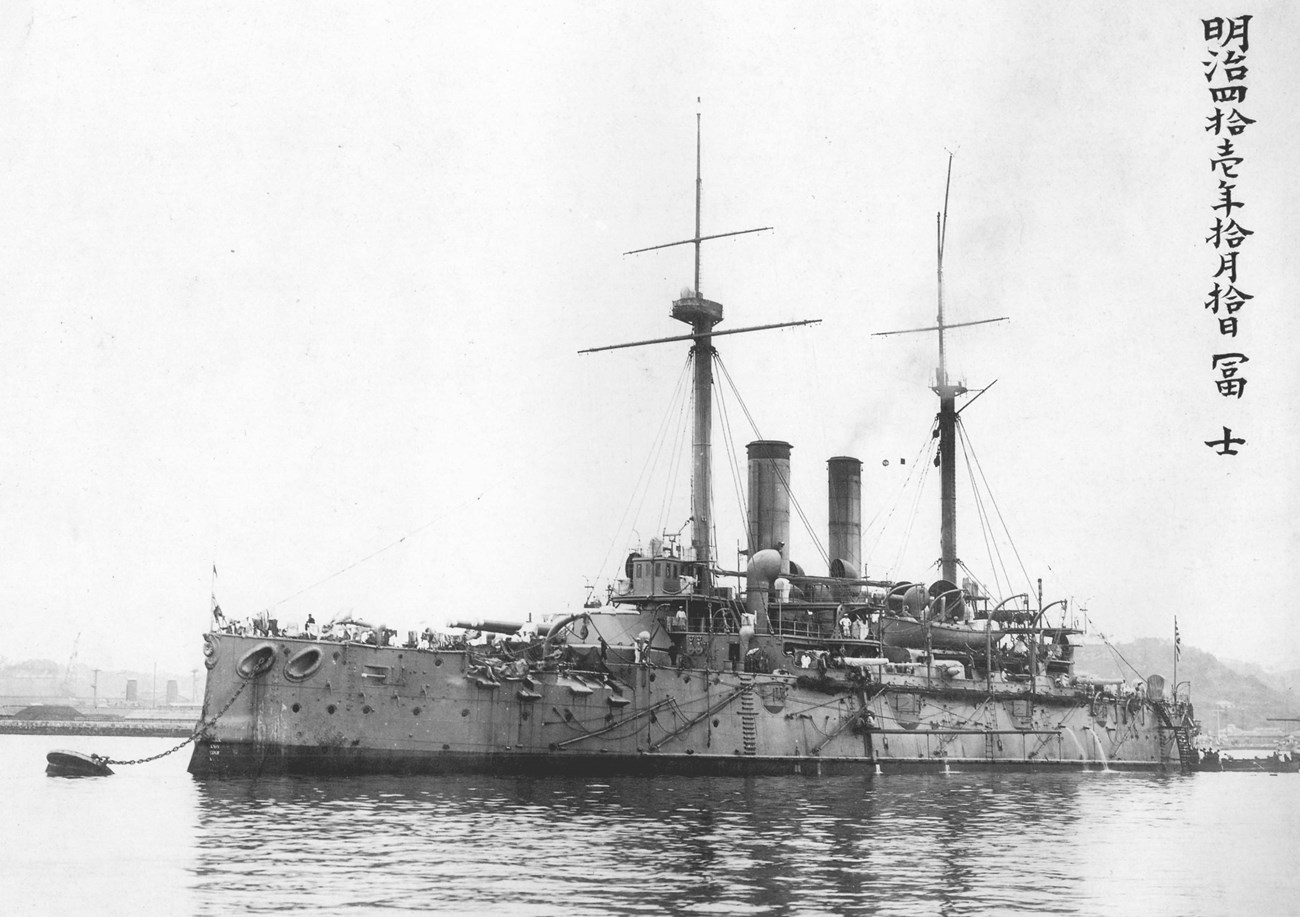

Public Domain/The Kure Maritime Museum of Science History

Global Politics and Weapons

The origin of these British-made naval guns on Kiska highlights the realities of global politics. In the late 1890s Japan desired to built up a powerful navy, but did not have the required shipbuilding expertise. They turned to Great Britain for help and ordered a number of battleships and cruisers. British-built and British-armed ships formed the mainstay of Japan’s World War I era fleet.

Following the Washington Arms Limitation Treaty of 1922, many older and obsolete ships were scrapped, but the guns were landed and placed in storage. These guns were emplaced as coastal defense guns in World War II, and can be found on many Japanese bases throughout the Pacific.

The most significant of these naval guns is a 6-inch gun on Little Kiska. Carrying the breech block number 8779 and the manufacturing date of 1894, the gun can be traced back to the first battleship the Japanese ordered from the United Kingdom: the IJNS Fuji. Today, this gun represents the only surviving gun of the Fuji, and the oldest evidence of the British-Japanese arms trade.

An analysis of the breech block numbers shows that the other two British-built 6-inch guns most probably came from the Japanese battleship IJNS Mikasa. The Mikasa is of national significance to Japan as it had been Admiral Togo’s flagship in the 1905 Battle of Tsushima. In this battle the Russian Pacific Fleet was annihilated, heralding Japan’s entry as a world power.

Usually military bases are developed and equipped based on strategic objectives. On occasion, however, there are examples of opportunistic adaptation.

When U.S. bombers damaged four Japanese supply ships beyond repair, the Japanese Navy landed the bow and aft guns carried on these ships for protection against submarines. Although of pre-World War I vintage, these outdated 3-inch guns added close-range firepower should an enemy attempt to land in Kiska Harbor. Today, only one of the guns remains in place near Trout Lagoon. Three have been removed from Kiska, but only one has so far been located (in Canada).

When the U.S. military recaptured Kiska in 1943, they discovered 105 heavy and medium guns left by the Japanese. These ranged from the larger guns emplaced for coastal defense, a range of anti-aircraft guns, of which the 75 mm was the most numerous, to assorted smaller artillery.

NPS/Dirk HR Spennemann

For Future Generations

The Kiska World War II battlefield forms part of the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument declared in 2008. The Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, collaborates with the National Historic Landmarks Program of the U.S. National Park Service in managing the battlefield for the benefit of future generations.

Recent collaborative research has documented the state of preservation of the Japanese guns (summer 2007) and assessed the cultural landscape values of the Kiska Battlefield (final report 2011). Kiska is the only battlefield in the United States, and world-wide one of only three, where there was no substantial human presence before the battle and where no subsequent alterations to the landscape have occurred. On Kiska the traces of the battle are still preserved in place and unchanged.

Because of the cold climate and the low levels of ultra-violet light, the preservation of wood and other organic matters is very good. At the same time, when the military forces withdrew from Kiska at the end of World War II, they left behind chemicals and petroleum products that can act as contaminants for the environment. In managing the battlefield for the benefit of future generations, the responsible federal agencies are striving to balance the preservation of one of the world’s most unique historic places against the needs of the environment and America’s wildlife.

Warning!

Kiska is a World War II battlefield. Unexploded ammunition is scattered throughout the landscape! Most guns have sharp metal edges. Be aware that it is illegal to interfere with any of the artifacts.

Preserve and Protect

To provide technical assistance in preserving and telling the compelling stories of this time period, the National Park Service Affiliated Area program works in partnership with the Aleutian World War II National Historic Area (https://www.nps.gov/aleu/index.htm) and the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge.

Kiska Island is federally owned and managed by the USFWS. As such, selling, receiving, transporting or damaging government property is illegal and may result in a felony conviction (18 USC Section 641 & 1361). Excavating, removing or damaging archeological sites on federal lands without permit is illegal and may also result in a felony conviction (16 USC 470).

Kiska – Nationally Recognized

Kiska is recognized as both a National Historic Landmark (NHL) and as part of the Aleutian Islands World War II National Monument, managed by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

In 1985 Kiska was designated a NHL for its World War II significance. The NHL Program, administered by the National Park Service, focuses attention on historic and archeological resources of exceptional value to the nation. The preservation and protection of nationally designated places is essential for their survival.

A joint U.S. National Park Service (NPS) and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) gun condition assessment in 2007, examined nearly 30 guns, many still in their original locations. These guns continue to constitute vital physical evidence of the Kiska battlefield, telling us much about the Japanese defensive strategy on the island during World War II in the Aleutians.

Text: Dirk HR Spennemann (Charles Sturt University, Australia) with contributions by Janet Clemens (NPS); based on the Kiska WWII guns condition and assessment reports.

Photographs: historic photographs, unless otherwise noted, are courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Color photographs were taken by Dirk HR Spennemann in 2007.

Support for this product was provided by the NPS-Alaska Regional Office. This publication was also made possible with the kind support of the following individuals which is gratefully acknowledged: Debra Corbett (FWS, Anchorage); Bruce Greenwood (formerly NPS, Anchorage); Janis Kozlowski (NPS, Anchorage); Jeff Williams (FWS, Homer); and the crew of the FWS research vessel MV Tiĝlax.

The Japanese World War II guns of Kiska are non-renewable cultural resources on a remarkable battlefield landscape.

Kiska Island, one of the western Aleutian Islands, is part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge and is administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Additional Information

- Alaska at War, 1941-1945: the Forgotten War Remembered, by Fern Chandonnet, editor (University of Alaska Press)

- The Thousand-Mile War: World War II in Alaska and the Aleutians, by Brian Garfield (University of Alaska Press)

- The Aleutian Warriors: A History of the 11th Air Force & Fleet Air Wing 4, by John Haile Cloe (Anchorage Chapter, Air Force Association and Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, Inc.)

- The Cultural Landscape of the World War II Battlefield of Kiska (pdf) by Dirk HR Spennemann, 2011, U.S. NPS, American Battlefield Protection Program

- Aleutian Islands, U.S. Army Center for Military History

- Japanese Occupation Site National Historic Landmark

- Scars on the Tundra: The Cultural Landscape of the Kiska Battlefield, Aleutians