Part of a series of articles titled On Their Shoulders: The Radical Stories of Women's Fight for the Vote.

Article

Should We Care What the Men Did?

By Brooke Kroeger

“Who cares what the men did?” That was all the book editor’s rejection note said.

It came in response to my proposal to recover the lost history of the legions of prominent men whom the women of the suffrage movement engaged in the 1910s to boost their aging, floundering campaign. Given the modest attention all the centennial activity of the past several years has paid to the men, that editor, and several others, may have had a point. Women’s suffrage was a women’s victory, after all.

“Who cares what the men did?” That was all the book editor’s rejection note said.

It came in response to my proposal to recover the lost history of the legions of prominent men whom the women of the suffrage movement engaged in the 1910s to boost their aging, floundering campaign. Given the modest attention all the centennial activity of the past several years has paid to the men, that editor, and several others, may have had a point. Women’s suffrage was a women’s victory, after all.

Imagine what it must have meant for “the thinking men of our country, the brains of our colleges, of commerce and literature,” in suffrage leader Carrie Chapman Catt’s phrase, to involve themselves with such gusto in a campaign designed to dilute their preeminence at the ballot box. For prominent men to back women’s rights was not new at this point. Illustrious figures such as Thomas Paine, Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Lloyd Garrison, and Frederick Douglass preceded the elites of the 1910s in outspoken support, but they did so as individuals, never as an organized state and national force. The Men’s League for Woman Suffrage became that and more. Chapters were said to have formed in thirty-five states with known activity strongest in New York, Illinois (where prominent Chicagoans formed the first US League chapter), Massachusetts, Connecticut, and California, known as John Hyde Braly’s California Political Equality League. Beyond his family, Braly considered his work for suffrage his proudest of many accomplishments.

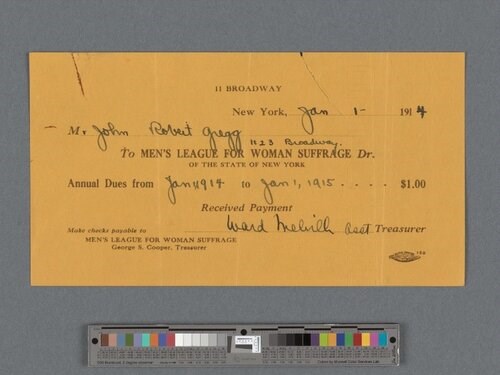

From the start in 1909 and until the vote was won, the Leagues worked under the direction of the women of NAWSA, the National American Woman Suffrage Association. “A blessing to us,” was how Catt described the men’s efforts to Theodora Bean of the New York Telegraph in 1912, a mere two years after the League’s founding. “We cannot overestimate its value.” The men even handled their own scut, previously understood as “women’s work.” Witness the signature on a dollar receipt for League annual dues of assistant treasurer Ward Melville, who eventually became a philanthropist and CEO of Thom McAnn Shoes.

Why was this male support crucial? “Legislators are mainly responsible to voters and voters only,” Laidlaw wrote. “In the majority of states in this country, determined women are besieging the Legislatures, endeavoring to bring about the submission of a woman suffrage amendment to the people. How long and burdensome is this effort on the part of non-voters, everyone knows.”

How could victory have happened without influential support from noteworthy members of the country’s overwhelmingly dominant voting bloc, its men? By 1910, after sixty years of campaigning, support for passage of women’s suffrage legislation was still weak. Only Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Idaho, and Washington had granted women the franchise, and among all forty-eight states, only Colorado, Idaho, and Utah had elected women representatives to their legislatures, and never more than three. At the federal level, no woman served in either US house until Montana sent Jeanette Rankin to Congress in 1917. The Senate did not follow until the 1932 election of Hattie Caraway in Arkansas (following Rebecca Latimer Felton’s one day of appointed representation from Georgia a decade before that.) Laidlaw offered up another reason for the League that everyone understood. “If a well-organized minority of men voters demand equal suffrage legislation from the Legislatures,” he wrote, “they will get it.”

In 1911 and in every New York and Washington, DC suffrage parade thereafter, the men marched together under Men’s League banners, at first braving catcalls and brickbats from the sidelines, as well as the sneers and eye-rolls of their peers out the windows of a Fifth Avenue clubhouse. Gradually their presence among the women became commonplace. They served on the movement’s finance and political action committees, used their political clout with governors and legislators, provided meeting space, testified before congressional committees, and ran interference with the police and in the courts. They joined their suffragist wives on state and cross-country recruitment trips. They orchestrated effective publicity campaigns, buoyed by the many writers, editors, and publishers in their leadership and ranks. They organized or attended mass meetings, banquets, a torchlight parade and a pageant, and state, national, and international suffrage conventions. They tallied votes on election nights and worked the streets. They even performed in movie shorts and one regrettable vaudeville sketch.

In September 1917, just weeks before the second New York referendum vote—a 1915 effort had failed—many of the Men’s Leaguers joined their wives in Saratoga Springs for an eleventh-hour strategy session. The New York Tribune reporter, Sarah Addington, couldn’t help but notice the envy directed at the state suffrage leaders Harriet Burton Laidlaw and Narcissa Cox Vanderlip because of their suffragist husbands. In his speech, Frank Vanderlip, then president of what is now Citibank, playfully referred to himself as a “victim of indirect influence.” That caused one wag to blurt, “If that is indirect influence, I want some.” Another suffragist told Addington that James Lees made Harriet Laidlaw “the luckiest woman in the world.” In 1932, after Laidlaw’s death, a condolence note from a fellow suffragist acknowledged the enormous contributions Harriet and other movement leaders had made, but the woman felt compelled to add of “Mr. Jimmie”: “We somehow owe him much more than we do all the women put together.”

A victory celebration at Cooper Union followed the New York State referendum’s passage on November 6, 1917. The crowd erupted in cheers as Laidlaw rose to say a few words, invited to speak by Gertrude Brown of the state party, who introduced the investment banker as the “head of those men who have given their lives, their efforts, and their fortunes to this cause.” Laidlaw deflected credit. “The women did it,” he said. “Not by any heroic action, but by hard, steady grinding and good organization. […] We men, too, have learned something,” he continued. “We who have been auxiliaries to the great woman’s suffrage party. We have learned to be auxiliaries.”

In 1919, after the federal suffrage amendment passed in Congress, Catt again praised all the men engaged in the suffrage movement, not just the League’s members, in an essay for the New York Times Magazine. She extolled their contributions and sacrifices and most pointedly that they “dared to espouse a despised cause.” After the victory, what credit was due the men did not take. The League does not appear by name in their memoirs or obituaries, save Laidlaw’s, which Harriet surely wrote, and Max Eastman’s, whose 1948 memoir includes his re-purposed 1912 early history of the League, published in The Woman Voter.

In this period, beyond the League itself, individuals like W. E. B. Du Bois and Dudley Field Malone played equally crucial movement roles. Neither of their names appears in either the 1910 or 1912 League membership rosters, nor do contemporaneous press reports identify them as League members, per se. Committed suffragists, however, they were. Du Bois, through the pages of the NAACP’s The Crisis, published two special suffrage symposia issues and wrote repeated editorials, urging African Americans to participate in the fight for women’s right to vote. The largely white, middle-class suffrage movement had repeatedly proved unwelcoming and insulting to black women suffragists. Du Bois argued that women’s suffrage served the black community in two significant ways: by doubling the potential number of black voters with the addition of women, and by keeping the right of all citizens to vote a paramount goal of those who had once been denied it. His reference was to the African-American men excluded from the nation’s polity until the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the US Constitution in 1870.

Suffragists of all factions lavished Malone with praise. (Malone eventually allied with Alice Paul’s National Woman’s Party, which had broken with NAWSA to pursue more militant strategies.) The suffragist columnist and poet, Alice Duer Miller, even wrote him an ode, chiding the long line of politicians and presidents who, like Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt, found it politically inexpedient to commit to federal action, until it wasn’t. Roosevelt made the turn to garner women’s votes in his unsuccessful run for president as a third-party candidate in 1912, but Wilson did not do so until his State of the Union address of December 2, 1918, three weeks after the Allies signed the Armistice with Germany that ended the fighting and six months before the congressional vote.

Duer’s poem:

Some men believe in suffrage

In a peculiar way,

They think that it is coming fast

But should not come to-day.

And others work and speak for it,

And yet you’ll sometimes find

Behind their little suffrage speech

A little axe to grind.

They put their Party interests first,

And suffrage well behind.

Of men who care supremely

That justice should be shown,

Who do not balk at sacrifice,

And make the cause their own,

I know, I think, of only one,

That’s Dudley Field Malone.

In a peculiar way,

They think that it is coming fast

But should not come to-day.

And others work and speak for it,

And yet you’ll sometimes find

Behind their little suffrage speech

A little axe to grind.

They put their Party interests first,

And suffrage well behind.

Of men who care supremely

That justice should be shown,

Who do not balk at sacrifice,

And make the cause their own,

I know, I think, of only one,

That’s Dudley Field Malone.

As to my own proposal to write about the “suffragents,” another house published the book in September 2017, just before the centennial of the New York State suffrage vote. It turns out that publisher might have tapped a vein after all. The book and others like it that acknowledge the men have generated dozens of appearances, reviews, and articles, prompted creation of the suffrage centennial media database, a special April 2019 suffrage centennial issue of the academic journal, American Journalism, and this past March, a book of new essays by journalism historians, Front Pages, Front Lines: Media and the Fight for Woman Suffrage. As many have noted, for women to share the spotlight with “the gents” also provides a detailed, century-old blueprint for men today who decide to engage as full-fledged allies in the on-going movement for women’s full equality.

Author Biography

Brooke Kroeger is a journalist and professor of journalism at the NYU Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute and the author of five books, most recently The Suffragents: How Women Used Men to Get the Vote. With Linda Steiner and Carolyn Kitch, she co-edited the newly published book of academic essays, Front Pages Front Lines: Media and the Fight for Women’s Suffrage, as well as creating and overseeing the suffrage centennial media resource database, SuffrageandtheMedia.org. Her previous books are Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist; Fannie: The Talent for Success of Writer Fannie Hurst; Passing: When People Can’t Be Who They Are; and Undercover Reporting: The Truth About Deception.

Bibliography

Addington, Sarah, “Plans for Last Suffragist State Vote Campaign Laid at Saratoga,” New York Tribune, Sept. 2, 1917, p. 9. “Chronicling America,” Library of Congress, accessed March 27, 2020.

Bean, Theodora, “The Greatest Woman in Suffrage and the Greatest Story Ever Written About Her,” New York Telegraph Sunday Magazine, Dec. 29, 1912, Section 2, p. 1. Women’s Suffrage and the Media, American Journalism: A Journal of Media History, accessed March 27, 2020.

Burton Laidlaw, Harriet, ed. James Lees Laidlaw, 1858-1932, University of California: Private Printing, 1932.

Catt, Carrie Chapman, “Why Suffrage Fight Took 50 Years.” New York Times Magazine, June 15, 1919, p. 82. Accessed March 27, 2020.

“Centuries of Citizenship: A Constitutional Timeline,” National Constitution Center, accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Forward Backward,” The Crisis, Vol. 2, No. 6, October 1911, pp. 243–244. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Heckling the Hecklers,” The Crisis, Vol. 3, No. 5, March 1912, pp. 195–196. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Suffering the Suffragettes,” The Crisis, Vol. 4, No. 2, June 1912, pp. 76–77. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Ohio,” The Crisis, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 81–82. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Votes for Women,” The Crisis, Vol. 4, No. 5, September 1912, p. 234. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “A Suffrage Symposium,” The Crisis, Vol. 4, No. 5, September 1912, pp. 240–247. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Hail Columbia!” The Crisis, Vol. 5, No. 6, April 1913, pp. 289–290. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Woman’s Suffrage," The Crisis, Vol. 6, No. 1, May 1913, p. 29. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Votes for Women,” The Crisis, Vol. 8, No. 4, August 1914, pp. 179–180. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Suffrage and Women,” The Crisis, Vol. 9, No. 4, February 1915, p. 182. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Woman Suffrage,” The Crisis, Vol. 9, No. 6, April 1915, p. 285. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Votes for Women,” The Crisis, Vol. 10, No. 4, August 1915, p. 177. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Votes for Women: A Symposium by Leading Thinkers of Colored America,” The Crisis, Vol. 10, No. 4, August 1915, pp. 178–192. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Woman Suffrage,” The Crisis, Vol. 11, No. 1, November 1915, pp. 29–30. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Votes for Women,” The Crisis, Vol. 15, No. 1, November 1917, p. 8. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Woman Suffrage,” The Crisis, Vol. 19, No. 5, March 1920, p. 234. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Eastman, Max. “Early History of the Men’s League,” The Woman Voter, October 1912, pp. 220-221. Women’s Suffrage and the Media, American Journalism: A Journal of Media History, accessed March 27, 2020.

Eastman, Max. Enjoyment of Living. New York: Harper, 1948.

“First Women to Serve in State and Territorial Legislatures," National Conference of State Legislatures, accessed March 27, 2020.

Kroeger, Brooke. The Suffragents; How Women Used Men to Get the Vote. Albany: SUNY Press, Excelsior Editions, 2017.

“Malone Breaks with Wilson Over Suffrage.” New York Tribune, September 8, 1917, p. 1. “Chronicling America,” Library of Congress, accessed March 27, 2020.

“Malone’s Letter to Wilson,” Woodrow Wilson Papers, Vol. 44, pages 167-168. Library of Congress, accessed March 27, 2020.

Middleton, George and James Lees Laidlaw, “Votes for Women: Struggle Education and Men’s League—WHY?” St. John’s Globe (New Brunswick), May 17, 1912. Women’s Suffrage and the Media, American Journalism: A Journal of Media History, accessed March 27, 2020.

Miller, Alice Duer, “Are Women People?” Columns, New York Tribune, 1914-1917, Via Project Gutenberg, accessed March 27, 2020.

Pauly, Garth E. “W.E.B. Du Bois on Woman Suffrage: A Critical Analysis of his Crisis Writings,” Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3, January 2000, pp. 383–410.

“Suffrage Centennial 2017-2020 Events,” Women’s Suffrage and the Media, American Journalism: A Journal of Media History, accessed March 27, 2020.

Wilson, Woodrow. Ed. Arthur S. Link. The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 44: August 21-November 10, 1917. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Wilson, Woodrow. “State of the Union Address: Woodrow Wilson (December 2, 1918)”. Infoplease, last updated February 11, 2017.

“Women Citizens Pledge Votes to Nation’s Welfare,” New York Times, November 8, 1917, p. 1. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Brooke Kroeger is a journalist and professor of journalism at the NYU Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute and the author of five books, most recently The Suffragents: How Women Used Men to Get the Vote. With Linda Steiner and Carolyn Kitch, she co-edited the newly published book of academic essays, Front Pages Front Lines: Media and the Fight for Women’s Suffrage, as well as creating and overseeing the suffrage centennial media resource database, SuffrageandtheMedia.org. Her previous books are Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist; Fannie: The Talent for Success of Writer Fannie Hurst; Passing: When People Can’t Be Who They Are; and Undercover Reporting: The Truth About Deception.

Bibliography

Addington, Sarah, “Plans for Last Suffragist State Vote Campaign Laid at Saratoga,” New York Tribune, Sept. 2, 1917, p. 9. “Chronicling America,” Library of Congress, accessed March 27, 2020.

Bean, Theodora, “The Greatest Woman in Suffrage and the Greatest Story Ever Written About Her,” New York Telegraph Sunday Magazine, Dec. 29, 1912, Section 2, p. 1. Women’s Suffrage and the Media, American Journalism: A Journal of Media History, accessed March 27, 2020.

Burton Laidlaw, Harriet, ed. James Lees Laidlaw, 1858-1932, University of California: Private Printing, 1932.

Catt, Carrie Chapman, “Why Suffrage Fight Took 50 Years.” New York Times Magazine, June 15, 1919, p. 82. Accessed March 27, 2020.

“Centuries of Citizenship: A Constitutional Timeline,” National Constitution Center, accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Forward Backward,” The Crisis, Vol. 2, No. 6, October 1911, pp. 243–244. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Heckling the Hecklers,” The Crisis, Vol. 3, No. 5, March 1912, pp. 195–196. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Suffering the Suffragettes,” The Crisis, Vol. 4, No. 2, June 1912, pp. 76–77. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Ohio,” The Crisis, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 81–82. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Votes for Women,” The Crisis, Vol. 4, No. 5, September 1912, p. 234. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “A Suffrage Symposium,” The Crisis, Vol. 4, No. 5, September 1912, pp. 240–247. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Hail Columbia!” The Crisis, Vol. 5, No. 6, April 1913, pp. 289–290. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Woman’s Suffrage," The Crisis, Vol. 6, No. 1, May 1913, p. 29. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Votes for Women,” The Crisis, Vol. 8, No. 4, August 1914, pp. 179–180. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Suffrage and Women,” The Crisis, Vol. 9, No. 4, February 1915, p. 182. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Woman Suffrage,” The Crisis, Vol. 9, No. 6, April 1915, p. 285. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Votes for Women,” The Crisis, Vol. 10, No. 4, August 1915, p. 177. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Votes for Women: A Symposium by Leading Thinkers of Colored America,” The Crisis, Vol. 10, No. 4, August 1915, pp. 178–192. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Woman Suffrage,” The Crisis, Vol. 11, No. 1, November 1915, pp. 29–30. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Votes for Women,” The Crisis, Vol. 15, No. 1, November 1917, p. 8. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Du Bois, W.E.B., “Woman Suffrage,” The Crisis, Vol. 19, No. 5, March 1920, p. 234. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Eastman, Max. “Early History of the Men’s League,” The Woman Voter, October 1912, pp. 220-221. Women’s Suffrage and the Media, American Journalism: A Journal of Media History, accessed March 27, 2020.

Eastman, Max. Enjoyment of Living. New York: Harper, 1948.

“First Women to Serve in State and Territorial Legislatures," National Conference of State Legislatures, accessed March 27, 2020.

Kroeger, Brooke. The Suffragents; How Women Used Men to Get the Vote. Albany: SUNY Press, Excelsior Editions, 2017.

“Malone Breaks with Wilson Over Suffrage.” New York Tribune, September 8, 1917, p. 1. “Chronicling America,” Library of Congress, accessed March 27, 2020.

“Malone’s Letter to Wilson,” Woodrow Wilson Papers, Vol. 44, pages 167-168. Library of Congress, accessed March 27, 2020.

Middleton, George and James Lees Laidlaw, “Votes for Women: Struggle Education and Men’s League—WHY?” St. John’s Globe (New Brunswick), May 17, 1912. Women’s Suffrage and the Media, American Journalism: A Journal of Media History, accessed March 27, 2020.

Miller, Alice Duer, “Are Women People?” Columns, New York Tribune, 1914-1917, Via Project Gutenberg, accessed March 27, 2020.

Pauly, Garth E. “W.E.B. Du Bois on Woman Suffrage: A Critical Analysis of his Crisis Writings,” Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3, January 2000, pp. 383–410.

“Suffrage Centennial 2017-2020 Events,” Women’s Suffrage and the Media, American Journalism: A Journal of Media History, accessed March 27, 2020.

Wilson, Woodrow. Ed. Arthur S. Link. The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, Volume 44: August 21-November 10, 1917. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Wilson, Woodrow. “State of the Union Address: Woodrow Wilson (December 2, 1918)”. Infoplease, last updated February 11, 2017.

“Women Citizens Pledge Votes to Nation’s Welfare,” New York Times, November 8, 1917, p. 1. Accessed March 27, 2020.

Last updated: December 14, 2020