Part of a series of articles titled Curious Collections of Fort Stanwix, The Oneida Carry Era.

Previous: Jesuit Ring

Next: King of Prussia Plate

Article

NPS image.

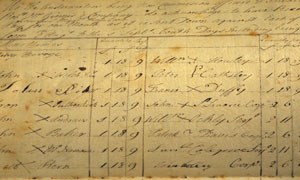

In December 2009, Fort Stanwix National Monument received two historic books as a donation in memory of Donald G. Hinman. The ledgers were originally owned by two brothers, Myndert and Barent Roseboom, ancestors of Mr. Hinman. Spanning nearly 20 years during the mid-18th century, the pages provide a glimpse into the Roseboom's military, trade, and personal experiences with the people they encountered between 1757 and 1775.

Since their donation, a park volunteer has led a project to transcribe, understand, and make available the contents of these journals. The initial task of transcribing the pages as a "word-for-word" project, has grown to better understand the historical nature of the entries, explain the monetary system used on these pages, and to define some of the terms and conventions written by the Roseboom's.

The folllowing entries from the Roseboom journals have been selected for this online exhibit. These pages were selected for their diversity and are representative of the many other entries contained within the journals.

NPS

Images showing the original page and transcription, along with a description of the entry, bookkeeping summary, and further questions brought to life from each page are presented throughout the exhibit.

Accompanying these pages is a glossary, which defines some of the 18th century words used in these books. A description of the British Monetary System is also provided to give information about the bookkeeping calculations.

This is an on-going project and the online exhibit will change as more pages are transcribed and further research is completed. We are happy to share this work and hope you enjoy the exhibit.

For more information or to request research access to the documents, please contact the Division of Cultural Resources.

NPS

In 1759, the British and French were in the middle of the French and Indian War. The NY Provincials were stationed at Camp Oswego, an important port on Lake Ontario used for trade and military movement.

This entry from the Myndert Roseboom ledger gives details of a military return for the NY Regiment at Oswego, NY. The entry, dated July 15, 1759, details the number of men under each captain's company within the first and second battalions. These two battalions would eventually go separate ways, one to Fort Niagara and the other staying behind to reconstruct Fort Ontario.

Each captain had at least one lieutenant, and multiple sergeants, corporals, and privates within their command. This entry is a snapshot in time and reveals the effectiveness of the regiment as indicated by the number of men who are "fit for duty" and others who are "sick and lame". This record detailing the number of men and various enlisted ranks and duties by battalions would have provided military leaders with essential information

NPS

Unlike most entries in this book, the left and right pages comprise one document. When reviewing the roster in total, it is evident that there are a number of 'strike-overs,' which are clearly visible on the original document. When this occurs, first, one number is entered and then another number is written over the first in an attempt to make a correction. Only the correct or final number is shown on the transcription.

A color-coded version of the transcription is also provided so that the original and final numbers can be more clearly seen. This is helpful when analyzing the totals since these are not always correct. Basic math was used on this page to add the columns and rows.

There was one mathematical error made when totaling the number of Lieutenants in Captain Rea's company. The "Fit for Duty" column shows two Lieutenants, while the final "Total" column shows only one. When the "Total" column is added, the correct number of Lieutenants was accounted for. This suggests that the author added the individual column totals to arrive at number given in the "Total" column instead of adding the column vertically. The author might have caught this mistake if he had cross checked his math!

Myndert Roseboom identified this book as a waste book, or type of book traditionally used in book keeping. Why would a military record be kept in Myndert's personal financial book? One would assume that the official military record, especially a regimental return, would be kept in a formal military ledger or orderly book.

Works Cited

De Lancey, Edward, Editor. 1891 Muster Rolls of New York Provincial Troops, 1755-1764. Reprinted 2007, Westminister, MD: Heritage Books, Inc.

NPS

This pay roll roster details the names of the men of Captain Robert McGinnis' company stationed at Fort Edward in August of 1757. The ranks of the men listed vary from privates to sergeants and corporals. In this company, it appears the two sergeants, William Oakly and Samuel Colegrove, both received officer's pay of 2 pounds, 11 shillings, 8 pence. The three corporals, John Lawarce, Patrick Davis, and John Bolley, all received 2 pounds, 6 shillings, and 6 pence. A single drummer, Silas Webb was also paid the same amount as a corporal officer. Sixty-four privates received 1 pound, 18 shillings, 9 pence.

NPS

Unlike most entries in this book, these pages are oriented in a "Landscape" orientation, across multiple pages.The second and fourth pages include a subtotal for the two pages visible when opened.Yet, there is no clear grand total for this pay roster.It would have been helpful to have a grand total, but this was not recorded.

NPS

As you can see on the original image, some individuals were able to sign their name, while others were only able to make a mark, typically an X, to indicate that they received their pay. These signatures or marks reveal the extent of literacy among enlisted men during the 18th century. Not many people had access to education that included both reading and writing and the need to provide a signature was not as common as it is today. Upon closer examination, you can see that some men tried to stylize their X or create their own unique mark.

The payroll was distributed by Lieutenant Myndert Roseboom, the owner of this book. The individual standing by to ensure that the payments were made to the individual soldiers was Goose Van Schiack, whose rank during this time is unknown. During the American Revolution Van Schiack became the Commandant of Fort Schuyler (Stanwix). By 1759, Lieutenant Roseboom would become Major Roseboom by 1759 and Lieutenant Colonel Roseboom by 1760 (DeLancey 1851: 543 & 545).

It would seem that official military records, especially pay records, would have been kept in formal military ledgers. Yet, Myndert Roseboom recorded this payment in his personal book, which he identifies as a waste book. A waste book is traditionally used in bookkeeping. Why was the military payroll roster entered into a personal book of Lieutenant Myndert Roseboom? It remains unknown why military records would be allowed to be entered into a personal book that was used for personal financial bookkeeping.

NPS

This page from the Barent Roseboom book details two separate debit transactions with James Melton. These entries occurred on different dates and, most likely, at different locations. The first shows that James Melton was loaned cash on October 25, 1764, which was paid to four individuals on his behalf. Merchants sometimes loaned money to third parties. Whoever was keeping this book at the time, paid Colonel Williams, James Cowden, Pellerson, and Grenville on behalf of Melton with the understanding that the original loan was to be repaid by James Melton.

The second entry details transaction on April 7th and 8th in 1780 (16 years after the first entry!). On these dates, Barent Roseboom received a pair of stilyards, a scale, a half-gallon Messina, and a lock from the storehouse. The stilyards and the scale beam would have been important in the business of trade and were used to weigh trade items like sugar or chocolate. These weighing instruments were likely brought to Skenesborough, NY from England.

Within this entry, the "Half Gallon of Messina," probably refers to lemon juice. Lemons and other citrus were grown near Messina, Italy during the 18th century. During this time, evidence was gaining that citrus juice, which contains Vitamin C, provided protection from scurvy. By 1795, lemon juice was included with rations in the British Navy (Baron 2009). Lemon juice was also sometimes added to the rum or grog rations given to soldiers.

NPS

NPS

The transactions recorded in the first entry illustrate a 'triangular payment' where three parties were involved in loaning and settling debt. Colonel Williams, James Cowden, Pellerson, and Grenville were paid money on behalf of James Melton. James Melton incurred the debt and would be responsible for paying Barent Roseboom the money given to these four individuals. Essentially, instead of having debt with numerous individuals, James Melton consolidated his debt with Barent Roseboom.

As with all entries in the Roseboom ledgers, more questions emerge as the texts are transcribed. A few of the questions that left us puzzled relate to the objects and the relationships of those listed on the page.

One such question that will likely remain unanswered is: what was the relationship between James Melton and Colonel Williams, James Cowden, Pellerson, and Grenville?

On April 8th, 1780, James Melton received a lock "put to the store house". Who's storehouse is being referred to in this description? Where these directions for Melton or is an 18th century description of a specific type of lock typically used to secure storehouses?

Finally, we know that Skenesborough was a popular town that held supplies for traders, merchants, and the general public. Where in Skenesborough did these transactions between Barent Roseboom and James Melton take place?

NPS

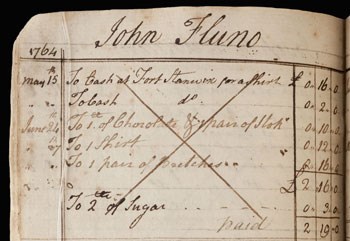

This page from the Barrent Roseboom ledger highlights transactions with John Fluno at Fort Stanwix on May 15, 1764. On this day, we know that Mr. Fluno was able to acquire a shirt and cash. Later, in June, he got a pound of chocolate and a pair of stockings. Since these entries are crossed out and a payment is noted in the amount of 2 pounds, 19 shillings, Mr. Fluno apparently covered his debt from these purchases. Yet, no payment is indicated for his July 7th transactions where Mr. Fluno received another shirt, along with a pair of britches and 2 pounds of sugar.

Pages like this one highlight the variety of goods that could be obtained within the colonial frontier setting. For example, cloth was one of the most traded items. Artifacts often reveal the many physical remains of trade and daily life, but textiles are not well preserved in the archeological record. Archeologists depend on accessories, such as pins or bale seals, to "see" cloth in the past. Clothing items often traveled to places like Fort Stanwix directly from Europe, so the trade of textiles would have been far reaching indeed. Ledgers and primary documents help to detail this trade and the importance of textiles within the 18th century trade economy.

Fluno also received chocolate, which was a fairly new commodity in the 18th century. Chocolate during this time period was different than can be found in the stores today. During this time, cocoa beans, from which chocolate is made, were grown and imported to the colonies from the "West Indies" or Caribbean Islands. The beans were usually ground and pressed into "cakes". It was thought to have medicinal properties and in 1761, Ben Franklin recommended chocolate as a cure for small pox (Theobald 2012). It is probably for this purpose that chocolate was being consumed, most likely as a hot chocolate drink, on the New York frontier.

NPS

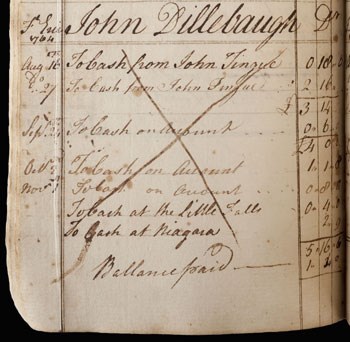

The penmanship and handwriting style on this page are consistent, indicating that both entries were made by the same person and that the debt or purchases were made to the same merchant. From this entry, it is known that in 1764 John Dillebaugh was at Fort Erie on August 16th and 27th, September 24th, October 2nd, and November 1st.

All of the entries for Mr. Dillebaugh are for cash. Merchants sometimes carried cash for individuals and paid off their debt at other locations. As seen on this page, cash was lent to John Dillebaugh from John Tingue, via Roseboom. John Tingue may have owed Roseboom money and, as a way of removing his debt, he lent John Dillebaugh cash. John Dillebaugh now owes Roseboom the amount that Mr. Tingue originally owed to Roseboom. In other words, Mr. Tingue transferred his debt to Mr. Dillebaugh. Mr. Dillebaugh now owes Roseboom. This is an example of a triangular payment.

As recorded on this page, when the debt is finally paid, the account is "crossed out". On some other ledger pages a "Contra" account is established. A "contra" account would be used to document the payment of the debt in part or in full. Both methods of settling accounts were used in the book entries of both ledgers.

In 1764, Fort Stanwix was occupied by the British military. Once the American Revolution began, John Fluno served with the 5th Regiment as an enlisted soldier under the command of Colonel Lewis Duboys, Lieutenant Colonel James Bruyn, and Lieutenant Colonel Marinus Willet (Roberts, 1897). We know that one battalion of the 5th NY Regiment served at Fort Stanwix under the command of Marinus Willett.

Did John Fluno ever return to Fort Stanwix as a soldier of the Contiental Army?

NPS

Historians often turn to military records because of the wealth of information they contain. Not only are large scale events or daily regimental activities documented, but individuals are often described in detail. This entry from Barent Roseboom’s ledger was recorded at Fort Ontario and involves the interjection of Major William W. Hogan of the New York Provincial Troops upon the debt of several individuals. Major Hogan resolved the debts of the named indviduals, several of whom are also known to have served in the colonial military. Connecting individuals to military records or information help to provide significantly more insight to the people that conducted business with Barent Roseboom. When we compare this list of men with the Muster Rolls of New York Provincial Troops, 1755-1764 for several names appear. In addition to recording the names of individuals enlisted, muster rolls also note who enlisted them and the specific date of their enlistment, where they were born, their stature or height, age, their trade or profession, and whether or not they were “fit for duty.”

New York State Historical Society. https://archive.org/details/musterrollsnewy00socigoog

The following information was found in the Muster Rolls of New York Provincial Troops, 1755-1764 for several specifically named individuals:

Augustus Pennell was born in Germany, enlisted in the NY Regiment on April 3, 1761, and was a professional cordwainer, or shoemaker. On June 21, 1761, Pennell was 36 years old and was average height at 5’8”.

John Dance was was 5’5” when he enlisted on April 2, 1762 at the age of 27. He was born in Ireland and served as a Labarour.

Peter Davis was mustered under Captain Street Hall on June 21, 1755. For 36 days of service, he was paid 2 pounds and 5 shillings.

Born in Ireland, Cornelius Duggon enlisted on April 15, 1761 at the age of 29. At the time, he stood 5’2” tall and served as a Baker for the NY Provincial Troops.

Benjamin Wampum was listed as serving within Captain Philip Schuyler’s is listed as a Private with the Campaign of 1760.

Sometimes information for individuals with more common names can be confusing. For instance, David Carter is mentioned several times in this muster document and likely refers to more than one individual. We know that a man named David Carter, age 35, served under Captain Ruben McLean in May of 1758. We also know that just one year later, David Carter, age 45, was serving as a Lockwood in the NY regiment in March 1759. Additionally, David Carter, age 33, was also a labourer in May 1761 and was noted again in March 1762 at age 49. Following the dates and ages listed, it can be assumed that more than one David Carter was enlisted in the NY regimental army between 1758 and 1762. A family tree or other documentation of the Carter family may reveal more information about David Carter.

NPS

While the debts were resolved in November 1762, this event was not recorded until October 1763. The amounts of the debts are significant because of the pay range that enlisted men received. Typically, a labourer would be paid about 1 pound, 17 shillings, 6 pence for one month of work. The debt owed to Barent ranges from 3 pounds, 16 shillings to 2 shillings.

In comparison, Majors serving in the NY regiment are not detailed within the payroll listings of the Muster Rolls of New York Provincial Troops, 1755-1764. Instead receipt of pay is listed as it relates to specific tasks or purposes. For instance, in April 1759, an entry in made in the Muster Rolls indicates that “to Majors £40 each, to furnish their respective tables.”

It is unclear whether Major Hogan stopped these men’s accounts with his own money and now the individuals owe Major Hogan OR if Major Hogan stopped these men’s military pay in order to resolve their debt to Barent Roseboom. The latter option would be similar to modern day wage-garnish practices. It is interesting to note the use of the word “stopped” instead of the term typically used in the ledgers to indicate a debt had been resolved (contra). Whether this entry notes a transfer of debt outside of Roseboom, or whether the accounts were resolved in a way that freed these men of debt to anyone, remains unknown at this point in time.

There are also three individuals listed at the bottom of the page that appear to have a continued open account with Barent. It is unclear if the amount they owe is represented as pounds, shillings, or pence. It is also unclear why their accounts were not stopped. Do they belong to Major Hogan’s company? Are they civilian individuals who also happened to be at Fort Ontario?

One of the main questions that may be solved by further studying the ledgers is: what did these individuals purchase or trade in order to become indebted to Roseboom?

Other questions relate to the nature of the transaction, specifically in regards to Major Hogan’s role. What were the motives of Major Hogan in helping Roseboom settle or stop the accounts of these individuals? Was there a personal benefit, professional gain, or was it an ethically or morally based decision for a commanding officer to help his troops? Could this be one of the earliest recordings of wage garnishing in colonial America?

To further explore the Muster Rolls of New York Provincial Troops, 1755-1764 visit: https://archive.org/details/musterrollsnewy00socigoog

NPS

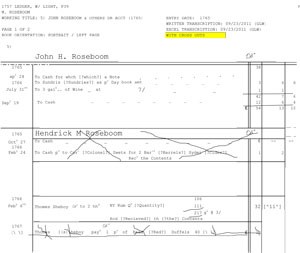

This two page entry details the debit and payoff of John H. Roseboom to Myndert Roseboom. The entries show the debits on the left page and credits on the right page. These transactions occurred at different times and are recorded to reflect ongoing business between John and Myndert during a two year period.

During the 18th century, the fur trade was booming and it is not uncommon to see beaver pelts traded and used as a form of currency. The final payment made by John occurred sometime after his final loan of cash on September 19, 1766. As detailed in the credit entry, a pack of beaver pelts weighing 88 lbs. were used to settle the remaining debt owed to Myndert in the sum of 33 pounds, 7 shilling, 4 pence.

NPS

In the entries detailing the transactions between Hendrick M. Roseboom and Myndert Roseboom, the debits are described on the left page and the account is credited by crossing out the debt entries.

The transactions with Hendrick are also a bit more complicated. On February 24, 1766, Hendrick was given cash which was paid to Corporal Swets. This cash was meant to pay for 2 barrels of cider. Myndert received the contents of the barrels as payment for his loan of cash to Hendrick. This triangular payment was typical of the 18th century frontier economy.

NPS

The transactions that include Thomes Sheboy also illustrate a triangular payment. On February 6th in 1766, Myndert receives NY rum on behalf of Hendrick from Thomes Sheboy. New York rum refers to rum that was distilled in New York from the molasses that was produced on sugar plantations in the Caribbean. Rum was a major commodity in the 18th century and sugar plantations in the Caribbean produced the majority of rum and molasses that was traded worldwide (McCusker 1989).

The large-scale distilling of rum began in the colonies as early as 1708 (Purvis 1998: 98). Because the rum that was distilled in the colonies was not aged, it was deemed lower quality. The New York rum traded between Sheboy and the Roseboom's likely came from Albany given the Roseboom's strong ties to the city and the Quackenbush family who operated the Quackenbush Still House Rum distillery in Albany (Quackenbush 1909).

NPS

On February 6, 1766, Thomes Sheboy is again involved with trade between Hendrick and Myndert.Sheboy was paid on behalf of Hendrick Roseboom. Sheboy received 1 pair of red "duffels", or thick wool blankets, usually white with a red stripe on the end. The number "40" may refer to the size of the blankets. This transaction cancelled a debt that Hendrick owed to Myndert.

In 1767, military records from the New York State Museum indicate that Hendrick M. Roseboom was a Captain of the 1st Company Militia of Albany. Listed as "rank and file" under his command was Thomes Sheboy and John Roseboom (Hastings 1898: 802). It is unknown if the John Roseboom referred to on this page is the same John Roseboom serving in the militia under Hendrick Roseboom, but the coincidence is interesting to note.

The triangular payments recorded on this page allude to the complex trade relationships maintained by Myndert Roseboom. Upon further investigation the personal relationships between those named on this page become more animated but only further research will truly inform those complexities. For example, what power and influence did Hendrick exude over Thomes Sheboy in order to complete the triangular transactions that occurred with Myndert? By 1766 Myndert was also in the militia. What was the relationship between the three men outside of their military roles?

If Myndert is crediting the debts incurred by Hendrick by crossing them out, it seems that the debt for the rum was never resolved.

In regards to John H. Roseboom's transactions, the first recorded transaction on April 24, 1765 is a bit mysterious. What was the 'Note' for?

The debit entries for John and Hendrick are recorded differently and Myndert records their settling of accounts differently. One is detailed as a "contra" while the other debts are simply crossed out or canceled. Why did Myndert record these transactions differently?

Part of a series of articles titled Curious Collections of Fort Stanwix, The Oneida Carry Era.

Previous: Jesuit Ring

Next: King of Prussia Plate

Last updated: August 8, 2022