Last updated: May 7, 2024

Article

A Bright Star in the Conservation Galaxy

National Parks have become so much a part of American culture and heritage that it's hard to imagine our country without them. These places are a way of preserving, unimpaired, some of the nation's natural wonders and inspirational human stories for "the enjoyment of future generations."

As early as 1929, Californians were increasingly concerned about the fate of their coastline. Development had swallowed most of the eastern seaboard and was accelerating along the Pacific and Gulf Coasts. Congressional reports recommended the creation of a system of national seashores to protect these vanishing landscapes and to provide public access to beaches.

In 1935, Conrad Wirth, then the Assistant Director of the National Park Service, recommended that 53,000 acres of Point Reyes be purchased "because of the peninsula's exceptional qualities and…accessibility to the concentrated population of Central California." The purchase price of $2.4 million, or about $45 per acre, seems like a great bargain in retrospect, but, with the country still in the grip of the Great Depression, the Congress thought otherwise. A new wave of land speculators aroused private conservation groups, who began to purchase Point Reyes themselves. The first 52 acres to be protected, in 1938, were the wetlands adjacent to Drakes Beach at a cost of $3,000. This property was deeded to Marin County. A dream was born, but it would take the extraordinary work of many individuals working together to fully realize that vision of a national seashore at Point Reyes.

Citizens Take Action

In the early 1940s, though recreation and beauty were of little concern to a country at war, local conservationists rallied once again. Mrs. Margaret McClure donated 2.9 acres of her Pierce Point Ranch to Marin County, providing access to the rugged, windswept shore now known as McClures Beach. Caroline Livermore, in concert with the Marin Conservation League, raised $15,000 to help Marin County buy 185 acres of Tomales Bay shoreline. Out of this nucleus grew Tomales Bay State Park, a refuge for those Ice Age survivors, the bishop pines.

Following World War II, the country experienced an economic boom period that led to great industrial and urban growth. The federal government invested heavily in highway construction and oil prices were low. More Americans had leisure time, owned cars, and spent time traveling to the coast than ever before. Coastal communities were erecting hotels and motels, restaurants and amusement parks to accommodate and entertain these tourists. This development boom extended to the Point Reyes Peninsula, already a favored vacation spot where well-to-do San Franciscans had built summer homes.

Loggers began cutting down trees on Inverness Ridge and surveyors were marking off lots above Limantour Spit. A sense of urgency to save the land gained momentum with help from a powerful ally—Clem Miller, the new Congressional representative for Marin County. With the support of U.S. Senator from California Clair Engle, Congressman Miller introduced legislation for a 35,000 acre park. Conservationists, organized as the Seashore Foundation, promoted the park dream in the face of opposition from developers and others fearful of losing their traditional way of life.

Creating Seashore Parks

In 1953, the first national seashore was established at Cape Hatteras, on the dynamic barrier island system off the North Carolina coast. Local, state, and federal advocates for protection of the Point Reyes peninsula were encouraged by this success. However, Drakes Bay Estates, with proposed development of over 400 housing units, began construction near Limantour Beach in 1956, lending urgency to the conservationists' endeavor.

In the late 1950s, legislation was first proposed to establish a national seashore at Point Reyes. When he took office, President John F. Kennedy announced two conservation agendas: the creation of national seashores and the adoption of the Wilderness Bill. Having spent summers throughout his life along the Massachusetts coast on Cape Cod, the protection of these beautiful wild shores was close to Kennedy's heart. Key players in these struggles were President Kennedy's Interior Secretary Stewart Udall, Sierra Club executive director David Brower, Clair Engle, Clem Miller, and author Harold Gilliam, among many others. In August of 1961, Cape Cod became the second national seashore, lending further momentum for the Point Reyes cause. The 1962 Sierra Club publication of Gilliam's book, Island in Time, brought much-needed publicity and a poetic voice to the campaign to protect Point Reyes. David Brower distributed a copy to every member of the 87th Congress.

PRNS Archives

In his book, Gilliam noted:

only 240 miles out of the 3700 miles of shoreline from Mount Desert Island to Corpus Christi are dedicated to public purposes. The National Park Service administers a mere 55 shore miles along the 1700 miles of Pacific Ocean coast.

Momentum in favor of the park grew, prompting legislation to acquire the full 53,000 acres first proposed in 1935 by Conrad Wirth. Twenty-seven years later, the dream of creating a National Park site at Point Reyes seemed to be coming true. Congressional floor debates for the Point Reyes legislation took place in the summer of 1962, during which battles were waged over incorporation of ranches and other private property into the seashore. The intense effort finally ended with the passage of S. 476 and, on September 13, 1962, President Kennedy signed The Point Reyes Authorization Act into law. Sadly, President Kennedy did not live to visit the newly created seashore.

PRNS Archives

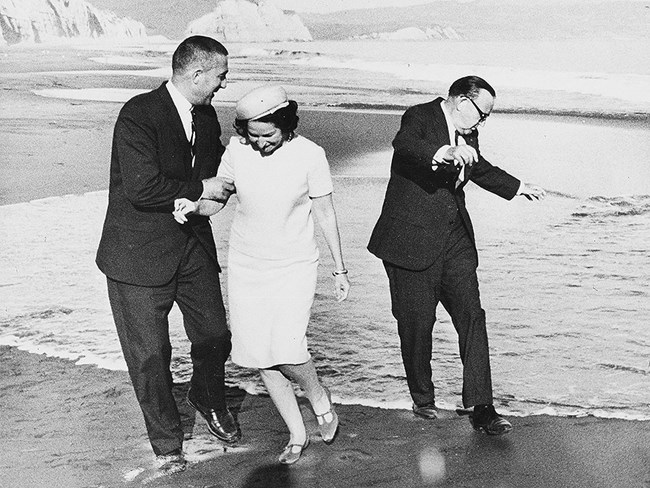

A Visit from the First Lady

On October 20, 1966, Lady Bird Johnson and Interior Secretary Stewart Udall came to Point Reyes to dedicate the park. Standing on Drakes Beach, with the Pacific as her backdrop, she warned that,

The growing needs of an urban America are quickening the tick of the conservation clock. Let us dedicate Point Reyes National Seashore to the vitality of the American people, and to generations yet unborn who will come here with the continent at their backs and gaze afar into immensity.

She called Point Reyes "a bright star in the galaxy of conservation achievements of the 1960s."

Congress, however, dragged its heels in appropriating the authorized funds. The original $14 million ran out before half of the 53,000 acres were acquired, and as land values soared in the years to come, the National Park Service was often just one step ahead of the developers. Again, individuals with a dream of protecting the area rallied together. More than 450,000 people wrote to the White House in support of park funding. Their efforts, organized by Peter Behr of Save Our Seashore, finally got the job done. On April 3, 1970, an additional $43,500,000 was appropriated to reach the goal of 53,000 acres.

Additional legislation established the Point Reyes Wilderness on October 18, 1976. This designated 23,370 acres of wilderness in the park, and an additional 8,003 of potential wilderness:

without impairment of its natural values, in a manner which provides for such recreational, educational, historic preservation, interpretation, and scientific research opportunities as are consistent with, based upon, and supportive of the maximum protection, restoration, and preservation of the natural environment within the area.

Legislation like the Marine Mammal Protection Act (1972) and the Endangered Species Act (1973) shaped the Seashore's protection of critical habitats.

In the 1970s, a new recognition evolved that the National Seashore must play a role in preserving the cultural heritage of the area. Kule Loklo, a replica of a Coast Miwok village at Bear Valley, was built as an introduction to thousands of years of Coast Miwok history. The Point Reyes Lighthouse was retired in 1975, and quickly became an icon and a visitor destination. The Seashore continues to support the traditions of dairies and ranches, even as thousands of acres of agricultural land has been lost state- and nation-wide.

Input from various community and environmental groups continued to influence policy at the National Seashore. The sentiment persisted that Point Reyes should protect the vibrant cultural history of the area, yet remain as wild as possible. It was recognized that merely protecting the area from development was not enough. Efforts had to be made to defend and re-establish the natural processes and critical habitats, which tied together and defined this place.

Tule elk, a species rescued from the brink of extinction, were reintroduced within a part of their former range at Point Reyes in the late 1970s. Efforts have been made to limit the effects of erosion on the streams critical to the populations of salmon and steelhead trout. Elephant seals returned to Point Reyes and hauled out onto isolated, local beaches. The first breeding colony formed in the early 1980s.

The Seashore entered a new era as it grappled with the best ways to protect and manage the assets in its care. Concerns over the protection of threatened and endangered species, the impacts of invasive species, the preservation of water quality, and the need for a baseline understanding of the resources led to increased scientific investigation and strategic planning.

Community groups, volunteers, and partners have always been key to Point Reyes' success, but a new emphasis was placed on working together to carry out research and monitoring, provide education, and present opportunities to understand and appreciate the park.

At the end of the 1900s, there was a growing awareness of new challenges facing parks. Global climate change and ocean health have led people to realize that the issues that threaten Point Reyes today are not just regional or national, but worldwide in scope.

As immense and overwhelming as problems may seem to an individual, remember what can be done when people have a dream. This place has always been a symbol of what can be accomplished when people work together—individuals taking an interest, getting involved, and making a change.

National Parks are one of the crucial places where citizens—both young and old—can develop a deeper understanding of our human interdependence with the increasingly fragile planet we inhabit. In our "progress" toward ever-more sophisticated technologies, we have harvested, mined, drilled, and developed our way through more natural resources than all of our ancestors combined. Focusing our sights on progress measured only through this same prism can’t be sustained. Wild places provide opportunities for progress measured on a different plane—conservation, simplicity, stewardship, wonder, community, and compassion.

Throughout the park's 60 years, millions of visitors have hiked the trails, surfed the waves, camped in its wilderness campgrounds, watched migratory whales and breeding elephant seals, and enjoyed the restful sound of waves lapping the shore. Only through our vigilance will the wild character of the forests and beaches—preserved through the efforts of our tireless predecessors—be enjoyed by generations to come.