Part of a series of articles titled On Their Shoulders: The Radical Stories of Women's Fight for the Vote.

Article

Nemesis: The South and the Nineteenth Amendment

By Marjorie J. Spruill

Why was the South so hostile to woman suffrage? As is often the case when southern institutions and practices are distinctive in comparison to the rest of the nation, the answer has to do largely with race and racism. The suffrage movement confronted and exhibited racism elsewhere: but nowhere else did it play such a crucial role in the story of woman suffrage.

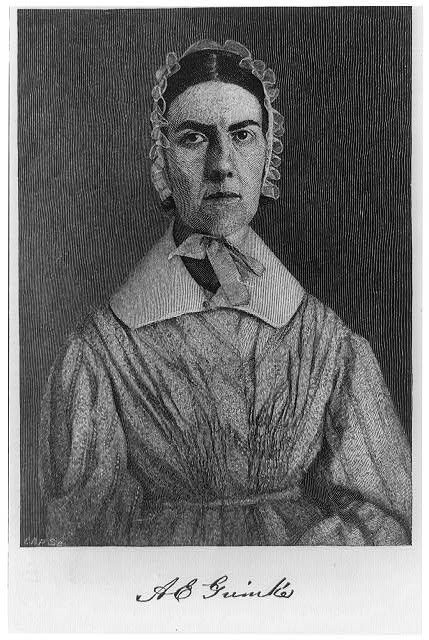

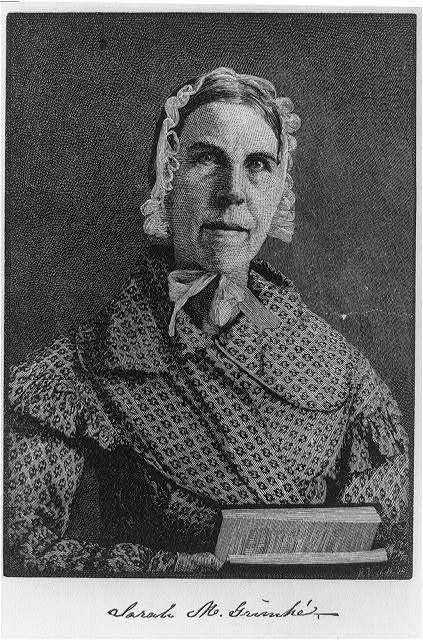

Two of the earliest women’s rights advocates, Sarah and Angelina Grimké, were white women from an elite, slaveholding family in South Carolina who moved north because of their opposition to slavery. Soon the Grimké Sisters began speaking and writing against slavery and for women’s rights. In 1836 Angelina published a book, Appeal to the Christian Women of the South, calling on them to use their influence against slavery. In 1839, with Angelina’s abolitionist husband, Theodore Weld, they published American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, a book depicting the horrors of slavery that was said to have inspired and informed Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The sisters were warned never to return to the South.[2]

During the Civil War, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton suspended work for women’s rights and founded the Women’s National Loyal League which petitioned for a constitutional amendment to end slavery, thus helping build public support for what became the Thirteenth Amendment. This also served to link the women’s movement with the hated antislavery movement in the minds of white southern conservatives. After the war, when women’s rights advocates began to focus on the vote, their goal was not woman suffrage but universal suffrage for all Americans regardless of gender or race. It appeared to white southern conservatives, eager to re-create the world they had lost to the extent possible, that northern suffragists shared the abolitionists’ dangerous belief in racial equality.[3]

Of course, suffragists were also disturbed by these Reconstruction amendments but for an entirely different reason: they protected the voting rights of formerly enslaved men, but enfranchised no women, black or white.[5] In 1869 the controversy over whether or not to support the Fifteenth Amendment divided suffragists into two rival organizations, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) led by Stanton and Anthony, who opposed it, and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) led by Lucy Stone and her husband Henry Blackwell, who supported it.[6]

In 1878, suffrage supporters introduced another similarly-worded federal suffrage amendment that they hoped would become the Sixteenth Amendment. But, because success would require many more decades of work, it became the Nineteenth Amendment. White southern conservatives were again outraged, continuing to insist that the Fifteenth Amendment was illegitimate and that the power to determine qualifications for voting should reside with the states without Congressional interference.

In South Carolina, a family of activists, the Rollin Sisters—Frances, Charlotte “Lottie,” Kate, and Louisa—African American women with powerful ties to legislators in the only state where there was a black majority during Reconstruction, held a Women’s Rights Convention in Columbia in 1870. A year later, with Lucy Stone’s encouragement, they founded a state suffrage organization affiliated with the AWSA.[8] However, that these earliest suffrage groups in the region were the work of white “carpetbaggers” and “scalawags” in Virginia, and black women active in Reconstruction-era politics in South Carolina, however, only strengthened white conservative southerners’ disdain for the suffrage movement and reinforced their idea that advocacy of women’s rights and the rights of African Americans were connected.[9]

Though a few southern women supported the suffrage movement in the 1870s and 1880s, there was no organized suffrage movement in the region until the 1890s. These late nineteenth century southern suffrage associations were composed solely of white women and excluded African American women. White suffragists in the South as well as in the North were indignant that black men had the vote when they did not: they either opposed black suffrage or did not wish to sabotage their own efforts by supporting it. Doing so would have doomed efforts of any southern woman to gain enfranchisement in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the nadir of race relations, when most white southern conservatives were intent on suppressing the black vote and used fraud and violence to do so.[10]

Mary Church Terrell, a native of Memphis who lived in Washington, D.C., was also a nationally prominent suffragist. Educated and affluent, she was one of the few African American women in this era invited to address NAWSA conferences. In her speeches and writings, she challenged African American men and women to support woman suffrage and white suffragists to support the struggles of African Americans.[12]

Terrell was a founder and first president of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), established in 1896. In this era, the rise in the number of educated, middle-class black women and the growing crisis in race relations made black women all the more determined to organize for collective self-help and resistance. African American suffragists were numerous and played a vital role in the suffrage movement. But rather than work in biracial suffrage organizations, in all parts of the United States they increasingly combined suffrage work with work for racial uplift and justice through African American women’s clubs, many affiliated with the NACW.[13] After the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was founded in 1909, Mary Church Terrell and Ida B. Wells-Barnett—both among the founders of the NAACP—also promoted woman suffrage and equal suffrage for all Americans through the organization and its magazine, The Crisis.

The woman suffrage movement in the South was led almost exclusively by well-connected white women of means who could safely weather the storm of opposition generated by their taking up this cause. Northern suffragists saw them as brave: southern critics saw them as dangerously naïve: as an Alabama state senator stated in a widely circulated pamphlet, “Politics and Patriotism,” these southern women allowed themselves “to be misled by bold women who are the product of the peculiar social conditions of our Northern cities into advocating a political innovation the realization of which would be the undoing of the South….These misguided daughters of the South are endorsing the principles for which Thad Stevens, Fred Douglass, Susan B. Anthony and other bitter enemies of the South contended, and if they succeed then indeed was the blood of their fathers shed in vain.” These women understood what they were doing, but saw woman suffrage as perfectly compatible with the ideas dominant among southerners of their race and class including white supremacy and state’s rights. They wanted the vote in part to support reforms such as abolition of child labor, prohibition of alcohol, improvement of schools and expansion of public health programs. But in regard to voting rights, their major complaint was that women like themselves—affluent, white, and educated—were excluded from the franchise.[15]

In the 1890s, leaders of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA)--formed when the NWSA and AWSA united in 1890--worked with these white southern women in a major drive to win the South for woman suffrage. Laura Clay of Kentucky, a key intermediary between northern and southern suffragists, pressed for this, reminding national leaders that they would have to win the support of two-thirds of each house of Congress and three-fourths of the states for a federal amendment to succeed. Here again race and racism play a major role in the southern suffrage story, helping determine the timing and strategy of this campaign and convincing suffragists they had a chance at success—even in the inhospitable South.[16]

NAWSA spent considerable time and resources pursuing this "southern strategy," locating suffrage sympathizers and organizing them, sending out recruiters, circulating literature, dispatching NAWSA leaders Susan B. Anthony and Carrie Chapman Catt on speaking tours through the region, and holding national conferences in Atlanta and New Orleans from which African Americans were banned. However, by 1903 most suffragists recognized that the strategy had failed; the region's politicians had refused, in the words of one Mississippi politician, to "cower behind petticoats" and "use lovely women" to maintain white supremacy. Instead, these conservative men found other means to do so that did not involve the "destruction" of women's traditional role as wives and mothers, dependent upon men for guidance and protection. These other means, which would be used to suppress the black vote in the South for many decades, included such measures as literacy tests, poll taxes, and “understanding clauses” requiring prospective voters to explain excerpts from the Constitution or other documents to the satisfaction of white registrars.[18]

A few southern suffragists in the Deep South, reluctant to give up on the “southern strategy,” initiated still more blatantly racist campaigns in 1906 and 1907, including a scheme to get a “white women only” amendment added to the Mississippi constitution. However, NAWSA refused to give its endorsement. Anna Howard Shaw, then president of NAWSA, insisted that such actions would be “contrary to the spirit of our organization.” Endorsing them would “re-act against ourselves” by suggesting “that we really don’t believe in the justice of suffrage, but simply that certain classes or races should dominate the government.” It would damage the movement, she believed, in the North and also in the West—the region where suffragists would finally achieve the crucial breakthroughs that gave momentum to the suffrage campaign and led to the passage of the federal amendment. The incident brought an end to the “southern strategy” designed to exploit the South’s “Negro problem” by suggesting woman suffrage as way to preserve white supremacy and suggested that there was, after all, a limit to the racism the NAWSA would support.[19]

Southern anti-suffragists also opposed woman suffrage on the grounds that black women supported it, for instance, distributing reprints of a pro-suffrage resolution adopted by the National Association of Colored Women (NACW). At times, anti-suffragists insisted that enfranchised African American women would be more demanding and difficult to deter than black men; they predicted that black women would register and vote in even larger numbers than white women, who would be unwilling to associate with African Americans at the polls. Moreover, as the suffragists became more focused on the federal woman suffrage amendment, white southern politicians denounced it as an unacceptable extension of the Fifteenth Amendment, a measure that would inspire renewed demands for black suffrage, which they insisted was “not dead but sleeping.”[21]

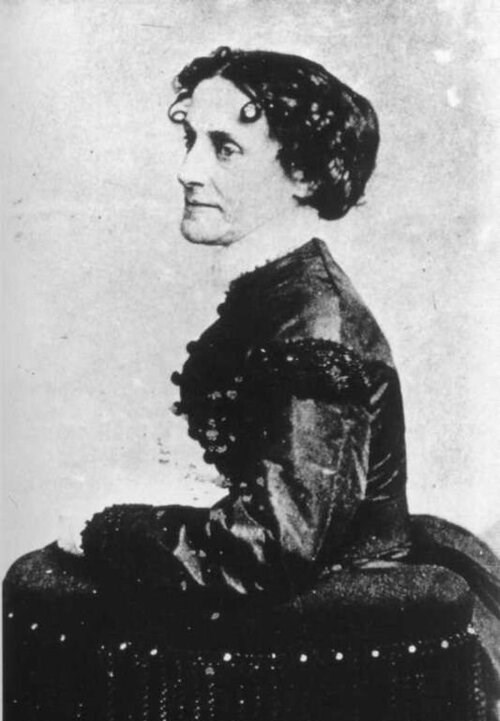

As anti-suffragists employed rabidly racist rhetoric to fight women’s enfranchisement, especially by federal amendment, white suffragists insisted that the race issue was irrelevant to the woman suffrage issue, a “non-issue” trumped up by their opponents. Nellie Nugent Somerville of Mississippi brushed aside the question, “How would woman suffrage apply to the American negress?” saying, “I answer, just as it applies to the American negro.” Mary Johnston of Virginia was relatively liberal compared to other white suffragists in the South. She was a novelist, the author of many best-selling books; her short story about a lynching and the psychological impact on all involved prompted Walter White of the NAACP to write her, saying he had never “read any story on this great national disgrace which moved me as yours did.” She believed strongly that women active in the suffrage movement should take care not to seek their own enfranchisement in such a way that black or poor white women would one day look back and conclude that the white suffragists had “betrayed” them or “excluded them from freedom.” Yet even she tried to counter the tactics of the anti-suffragists by denying that state suffrage amendments would enfranchise large numbers of African American women, insisting that only “a few educated, property-owning colored women will vote, but not the mass of colored women.”[22]

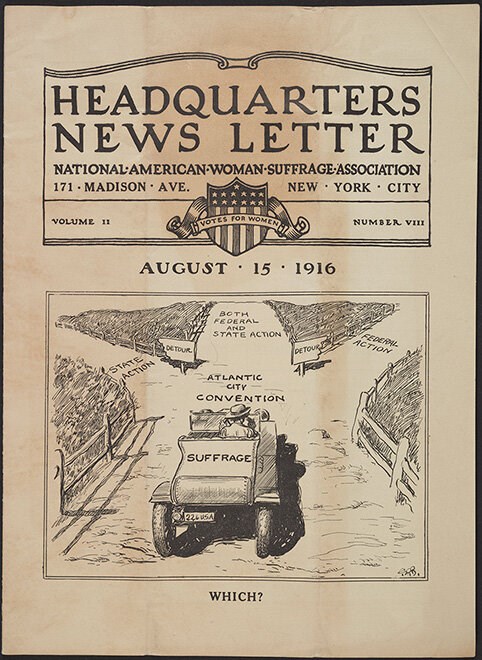

A minority of white southern suffragists could not bring themselves to support a federal suffrage amendment. When in 1913, NAWSA, prodded into action by Alice Paul and her associates, renewed its campaign for a federal suffrage amendment, New Orleans suffrage leader Kate Gordon decided it was time that southern suffragists go their own way—founding a new organization, the Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference (SSWSC). Gordon insisted the NAWSA was just wasting its time and money promoting “another federal suffrage amendment” in the South, and demanded that the NAWSA turn over the South to her leadership.[23]

Most southern suffragists, however, did not follow Kate Gordon's lead. Few were willing to renounce federal suffrage when it might be their only means of gaining the vote. In fact, after one of Gordon’s tirades against NAWSA leaders, state suffrage organizations in Tennessee and Alabama formally rebuked Gordon and her attempts to lead a southern revolt against NAWSA and the federal amendment. Of the leading suffragists, only Clay and Gordon were so committed to the concept of state sovereignty that they ultimately refused to support, and indeed, opposed the federal suffrage amendment.[24]

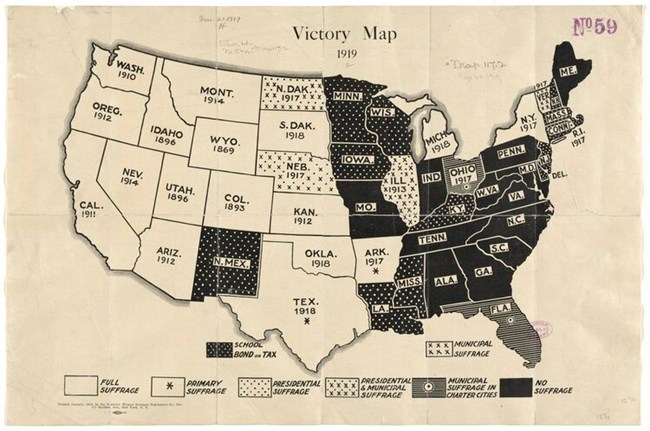

When in June 1919 Congress finally submitted the proposed Nineteenth Amendment to the states for ratification, the leaders of the woman suffrage movement in the southern states found themselves fighting one another as well as the antis—a situation that did nothing to help the cause. In Louisiana, Gordon and other advocates of woman suffrage only through state action combated both federal amendment supporters and the anti-suffragists, creating a three-way struggle in which no form of woman suffrage was adopted. During the final, bitter battle which took place in Nashville, Tennessee, both Gordon sisters and Laura Clay actually campaigned against ratification of "this hideous amendment," though Clay expressed "a great distaste" at being publicly associated with the despised “antis.”[26]

For suffragists whose hopes were now pinned on the federal suffrage amendment, it was worrisome that the last state fight over ratification would take place in the South. Yet with only one more state needed for ratification, and no other state legislatures scheduled to meet before the upcoming November 1920 presidential election, they were lucky that the governor of Tennessee—pressured by President Woodrow Wilson—agreed to call a special session. Still, the southern setting of the suffrage movement’s “Armageddon” —the final, desperate battle--meant that the outcome was far from certain.[27]

Tennessee ratified the amendment on August 18, 1920, but by just one vote. Even then, anti-suffrage legislators, using parliamentary tricks, called for reconsideration, pressured men who had voted “aye” to change their votes, and held a “Mass Meeting…To Save the South” in Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium. Desperate anti-suffrage lawmakers fled the state to prevent a quorum, but in vain. Tennessee confirmed its vote for ratification, and the governor rushed the bill to Washington where Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby received and signed it on August 26, 1920--in the wee hours of the night before antis could secure an injunction or by some other means interfere with certification of the Nineteenth Amendment.[29]

A “nemesis” is by definition an arch-enemy, antagonist, or foe, determined to thwart its adversary.[30] For woman suffrage, the nemesis was clearly the South, the region of the country where the woman suffrage movement encountered the strongest opposition and the least success.

After ratification, NAWSA president Carrie Chapman Catt observed ruefully that, in 1920, when “the final victory came to the woman suffrage movement”…suffragists knew that their victory had, even then, been virtually wrung from hesitant and often resentful political leaders.”[31] She was speaking of the leaders who had eventually conceded; in the states that had refused to ratify, conservative white lawmakers continued to resent and to resist woman suffrage. Implementation of the federal woman suffrage amendment was slow--when it happened at all.

After adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment, African American women outside the South began voting right away. Ida B. Wells-Barnett and members of her Alpha Suffrage Club, had already been voting—and playing an important role in Chicago politics—since Illinois passed a state suffrage amendment in 1913. However, most African American women lived in the South. And when they turned out to register to vote in great numbers, they found—as many had feared and predicted—that the measures adopted by southern states to prevent black men from voting were quickly adapted to apply to them. Pushing back, African American women established “Colored women’s voter’s leagues” throughout the South, to aid black women seeking to qualify to vote on how to deal with white opposition. And with the aid of the NAACP, they carefully gathered evidence about racial and gender discrimination in violation of the Nineteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to present to Congress. However, Congress refused to intervene.[33]

It would take forty-five more years, and a massive voting rights movement in which black women played a leading role, before Congress finally used its authority to enforce the Nineteenth Amendment—and the Fifteenth—through the Voting Rights of 1965. After that, African American women of the South were finally able to fully claim the right to vote they had won in 1920.

Author Biography

Marjorie J. Spruill, Distinguished Professor Emerita, University of South Carolina, writes about women and politics from the woman suffrage movement to the present and about the American South. Her most recent book is Divided We Stand: The Battle Over Women’s Rights and Family Values That Polarized American Politics (Bloomsbury 2017). She is the author of New Women of the New South: The Woman Suffrage Movement in the Southern States (Oxford University Press) and five edited books on woman suffrage. In 2020 she is publishing a new edition of One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement, first published in 1995 as the companion volume to the PBS documentary “One Woman, One Vote.” Spruill was a consultant to the National Archives for its exhibit, “Rightfully Hers” and an advisor for the documentary “By One Vote: Woman Suffrage in the South,” produced by Nashville Public Television. Her work was supported by fellowships from the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and a research award from the Gerald R. Ford Foundation. She spent a year at the National Humanities Center. Spruill co-edited a textbook on the American South and two multi-volume anthologies about the “lives and times” of women in South Carolina and Mississippi. During her career, she was a professor at the University of Southern Mississippi, Vanderbilt (where she was an Associate Provost), and the University of South Carolina. She lives in Folly Beach, SC.

Footnotes

[1] Marjorie Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South: The Leaders of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the Southern States (Oxford University Press, 1993)

[2] Gerda Lerner, The Grimké Sisters from South Carolina: Pioneers for Women's Rights and Abolition (University of North Carolina Press, 2004); Carol Berkin, Civil War Wives: The Lives and Times of Angelina Grimké Weld, Varina Howell Davis, and Julia Dent Grant (New York: Vintage Books, 2010).

[3] On white southern conservatives’ efforts to preserve much of antebellum culture, see Charles Reagan Wilson, Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865-1920 (Athens, Ga. University of Georgia Press, 1989).

[4] Faye E. Dudden, Fighting Chance: The Struggle Over Woman Suffrage and Black Suffrage in Reconstruction America (Oxford University Press, 2014); Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South, 19-26; Marjorie Spruill (Wheeler), ed., Votes for Women: The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee, the South, and the Nation (University of Tennessee Press, 1995), anti-suffrage broadsides 300-311.

[5] “Voting Rights and the 14th Amendment,” National History Education Clearinghouse

[6] Dudden, Fighting Chance.

[7] Jennifer Davis McDaid, “Woman Suffrage in Virginia”.

[8] Willard Gatewood, “The Rollin Sisters: Black Women in Reconstruction South Carolina,” in Marjorie J. Spruill, Valinda Littlefield, and Joan Marie Johnson, eds., South Carolina Women: Their Lives and Times (University of Georgia Press, 2010): 50-67.

[9] Conservative white southerners used the term “carpetbaggers” for northerners who came to the South and cooperated with the federal government’s efforts to “reconstruct” the South after the Civil War. “Scalawag” was the equally derisive term for a white southerner who worked with them.

[10] Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South; Rayford W. Logan, The Negro in American Life and Thought: The Nadir, 1877-1901 (New York: Dial Press, 1954)

[11] Edith Mayo, “African American Women Leaders in the Suffrage Movement, Turning Point Suffragist Memorial"; Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, “African American Women and the Woman Suffrage Movement,” Chapter Ten, and Wanda A. Hendricks, “Ida B. Wells-Barnett and the Alpha Suffrage Club of Chicago,” Chapter Seventeen, in Marjorie J. Spruill ed., One Woman One Vote, Second Edition.

[12] Mary Church Terrell, National Park Service; Mayo, “African American Women Leaders.”

[13] Terborg-Penn, “African American Women and the Woman Suffrage Movement”; Martha S. Jones, All Bound Up Together: The Women Question in African American Public Culture, 1830-1900 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2007).

[14] Adele Logan Alexander, “Adella Hunt Logan, The Tuskegee Woman’s Club, and African Americans in the Suffrage Movement,” in Marjorie Spruill (Wheeler), ed., Votes for Women: The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee, the South, and the Nation (University of Tennessee Press, 1995): 71-104; Adele Logan Alexander, Princess of the Hither Isles: A Black Suffragist's Story from the Jim Crow South (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).

[15] Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South, Alabama state senator quoted 25-26, 38-58.

[16] Carrie Chapman Catt and Nettie Rogers Shuler, Women Suffrage and Politics: The Inner Story of the Suffrage Movement (Seattle & London: University of Washington Press, 1923), 88-89; Marjorie J. Spruill, Chapter Nine, "Bringing in the South: Southern Ladies, White Supremacy, and State’s Rights in the Fight for Woman Suffrage," in Spruill, ed., One Woman One Vote; Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South, 113-125.

[17] Ibid., 113-120.

[18] Ibid., 116-120.

[19] Ibid., 120-25, quotations 121.

[20] Ibid. 30-37, 125-32; Spruill (Wheeler), Votes for Women, Pro-suffrage literature, 290-91. Anti-suffrage literature, 302-11; Anastatia Sims, “Armageddon in Tennessee: The Final Battle Over the Nineteenth Amendment,” Chapter Twenty-one, in Spruill, One Woman One Vote, Second Edition.

[21] Spruill, Votes for Women, 303, 304; Sims, Chapter Twenty-one.

[22] Ibid., 106, 125–32, Somerville quotation on 128, White quotation on 106.

[23] Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South, 133–53.

[24] Ibid., 154–80.

[25] Ibid., 159-71, quotation,163.On Catt’s “Winning Plan,” see Robert Booth Fowler, "Carrie Chapman Catt: Strategist," Chapter Nineteen, in Spruill, ed., One Woman One Vote.

[26] Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South, 172–80, quotations, 176.

[27] Sims, “Armageddon in Tennessee”; Weiss, Elaine, “The Woman’s Hour”: The Great Fight to Win the Vote (New York: Penguin Random House, 2018).

[28] Spruill (Wheeler), Votes for Women, 302-311, quotations, 305; Suzanne Lebsock, “Woman Suffrage and White Supremacy: A Virginia Case Study,” in Visible Women: New Essays on American Activism, ed. Nancy Hewitt and Suzanne Lebsock (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 62–100.

[29] Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South, 30-37; Spruill (Wheeler), Votes for Women, see anti-suffrage broadsides, 300-311, quotations 305, 311.

[30] “Nemesis,” Oxford Languages

[31] Carrie and Shuler, Women Suffrage and Politics, 5.

[32] Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South, 181; Terborg-Penn, Chapter Ten, in Spruill, ed. One Woman One Vote, Second edition.

[33] Ibid.

Bibliography

Alexander, Adele Logan. Princess of the Hither Isles: A Black Suffragist’s Story from the Jim Crow South. Yale University Press, 2019.

Baker, Jean H., ed. Votes for Women: The Struggle for Suffrage Revisited. Oxford University Press, 2002.

Berkin, Carol. Civil War Wives: The Lives and Times of Angelina Grimké Weld, Varina Howell Davis, and Julia Dent Grant. New York: Vintage Books, 2010.

Catt, Carrie Chapman, and Nettie Rogers Shuler. Women Suffrage and Politics. the Inner Story of the Suffrage Movement. University of Washington Press, 1923.

Dudden, Faye E. Fighting Chance: The Struggle over Woman Suffrage and Black Suffrage in Reconstruction America. Oxford University Press, 2011.

Fowler, Robert Booth. Carrie Catt: Feminist Politician. Northeastern University Press, 1986.

Fuller, Paul E. Laura Clay and the Woman’s Rights Movement. University Press of Kentucky, 1992.

Gatewood, Willard. “The Rollin Sisters: Black Women in Reconstruction South Carolina,” in Marjorie J. Spruill, Valinda Littlefield, and Joan Marie Johnson, eds., South Carolina Women: Their Lives and Times. University of Georgia Press, 2010: 50-67.

Giddings, Paula. Ida. A Sword Among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the Campaign Against Lynching. Amistad, 2008.

Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth. Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina 1896-1920. University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Harley, Sharon, and Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, eds. The Afro-American Woman: Struggles and Images. National University Publications, 1981.

Jones, Martha S. All Bound Up Together: The Woman Question in African American Public Culture, 1830-1900. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Lerner, Gerda. The Grimké Sisters from South Carolina: Pioneers for Women’s Rights and Abolition. University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Newman, Louise Michele. White Women's Rights: The Radical Origins of Feminism in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Spruill, Marjorie J. One Woman One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement. NewSage Press, First edition 1995, Second edition 2020.

Spruill (Wheeler), Marjorie. New Women of the New South: The Leaders of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the Southern States. Oxford University Press, 1993.

———. Votes for Women!: The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee, the South, and the Nation. University of Tennessee Press, 1995.

---------. Hagar. By Mary Johnston. Edited with an Introduction by Marjorie Spruill (Wheeler). University Press of Virginia, 1994.

Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn. African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote: 1850-1920. Indiana University Press, 1998.

Weiss, Elaine F. The Woman's Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote, New York: Penguin/Random House, 2019.

Wilson, Charles Reagan. Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865-1920. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1980.

Yellin, Carol Lynn, and Janann Sherman. The Perfect 36: Tennessee Delivers Woman Suffrage. Edited by Ilene J Cornwell. Iris Press, 1998.

Marjorie J. Spruill, Distinguished Professor Emerita, University of South Carolina, writes about women and politics from the woman suffrage movement to the present and about the American South. Her most recent book is Divided We Stand: The Battle Over Women’s Rights and Family Values That Polarized American Politics (Bloomsbury 2017). She is the author of New Women of the New South: The Woman Suffrage Movement in the Southern States (Oxford University Press) and five edited books on woman suffrage. In 2020 she is publishing a new edition of One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement, first published in 1995 as the companion volume to the PBS documentary “One Woman, One Vote.” Spruill was a consultant to the National Archives for its exhibit, “Rightfully Hers” and an advisor for the documentary “By One Vote: Woman Suffrage in the South,” produced by Nashville Public Television. Her work was supported by fellowships from the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and a research award from the Gerald R. Ford Foundation. She spent a year at the National Humanities Center. Spruill co-edited a textbook on the American South and two multi-volume anthologies about the “lives and times” of women in South Carolina and Mississippi. During her career, she was a professor at the University of Southern Mississippi, Vanderbilt (where she was an Associate Provost), and the University of South Carolina. She lives in Folly Beach, SC.

Footnotes

[1] Marjorie Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South: The Leaders of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the Southern States (Oxford University Press, 1993)

[2] Gerda Lerner, The Grimké Sisters from South Carolina: Pioneers for Women's Rights and Abolition (University of North Carolina Press, 2004); Carol Berkin, Civil War Wives: The Lives and Times of Angelina Grimké Weld, Varina Howell Davis, and Julia Dent Grant (New York: Vintage Books, 2010).

[3] On white southern conservatives’ efforts to preserve much of antebellum culture, see Charles Reagan Wilson, Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865-1920 (Athens, Ga. University of Georgia Press, 1989).

[4] Faye E. Dudden, Fighting Chance: The Struggle Over Woman Suffrage and Black Suffrage in Reconstruction America (Oxford University Press, 2014); Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South, 19-26; Marjorie Spruill (Wheeler), ed., Votes for Women: The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee, the South, and the Nation (University of Tennessee Press, 1995), anti-suffrage broadsides 300-311.

[5] “Voting Rights and the 14th Amendment,” National History Education Clearinghouse

[6] Dudden, Fighting Chance.

[7] Jennifer Davis McDaid, “Woman Suffrage in Virginia”.

[8] Willard Gatewood, “The Rollin Sisters: Black Women in Reconstruction South Carolina,” in Marjorie J. Spruill, Valinda Littlefield, and Joan Marie Johnson, eds., South Carolina Women: Their Lives and Times (University of Georgia Press, 2010): 50-67.

[9] Conservative white southerners used the term “carpetbaggers” for northerners who came to the South and cooperated with the federal government’s efforts to “reconstruct” the South after the Civil War. “Scalawag” was the equally derisive term for a white southerner who worked with them.

[10] Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South; Rayford W. Logan, The Negro in American Life and Thought: The Nadir, 1877-1901 (New York: Dial Press, 1954)

[11] Edith Mayo, “African American Women Leaders in the Suffrage Movement, Turning Point Suffragist Memorial"; Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, “African American Women and the Woman Suffrage Movement,” Chapter Ten, and Wanda A. Hendricks, “Ida B. Wells-Barnett and the Alpha Suffrage Club of Chicago,” Chapter Seventeen, in Marjorie J. Spruill ed., One Woman One Vote, Second Edition.

[12] Mary Church Terrell, National Park Service; Mayo, “African American Women Leaders.”

[13] Terborg-Penn, “African American Women and the Woman Suffrage Movement”; Martha S. Jones, All Bound Up Together: The Women Question in African American Public Culture, 1830-1900 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2007).

[14] Adele Logan Alexander, “Adella Hunt Logan, The Tuskegee Woman’s Club, and African Americans in the Suffrage Movement,” in Marjorie Spruill (Wheeler), ed., Votes for Women: The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee, the South, and the Nation (University of Tennessee Press, 1995): 71-104; Adele Logan Alexander, Princess of the Hither Isles: A Black Suffragist's Story from the Jim Crow South (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).

[15] Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South, Alabama state senator quoted 25-26, 38-58.

[16] Carrie Chapman Catt and Nettie Rogers Shuler, Women Suffrage and Politics: The Inner Story of the Suffrage Movement (Seattle & London: University of Washington Press, 1923), 88-89; Marjorie J. Spruill, Chapter Nine, "Bringing in the South: Southern Ladies, White Supremacy, and State’s Rights in the Fight for Woman Suffrage," in Spruill, ed., One Woman One Vote; Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South, 113-125.

[17] Ibid., 113-120.

[18] Ibid., 116-120.

[19] Ibid., 120-25, quotations 121.

[20] Ibid. 30-37, 125-32; Spruill (Wheeler), Votes for Women, Pro-suffrage literature, 290-91. Anti-suffrage literature, 302-11; Anastatia Sims, “Armageddon in Tennessee: The Final Battle Over the Nineteenth Amendment,” Chapter Twenty-one, in Spruill, One Woman One Vote, Second Edition.

[21] Spruill, Votes for Women, 303, 304; Sims, Chapter Twenty-one.

[22] Ibid., 106, 125–32, Somerville quotation on 128, White quotation on 106.

[23] Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South, 133–53.

[24] Ibid., 154–80.

[25] Ibid., 159-71, quotation,163.On Catt’s “Winning Plan,” see Robert Booth Fowler, "Carrie Chapman Catt: Strategist," Chapter Nineteen, in Spruill, ed., One Woman One Vote.

[26] Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South, 172–80, quotations, 176.

[27] Sims, “Armageddon in Tennessee”; Weiss, Elaine, “The Woman’s Hour”: The Great Fight to Win the Vote (New York: Penguin Random House, 2018).

[28] Spruill (Wheeler), Votes for Women, 302-311, quotations, 305; Suzanne Lebsock, “Woman Suffrage and White Supremacy: A Virginia Case Study,” in Visible Women: New Essays on American Activism, ed. Nancy Hewitt and Suzanne Lebsock (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 62–100.

[29] Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South, 30-37; Spruill (Wheeler), Votes for Women, see anti-suffrage broadsides, 300-311, quotations 305, 311.

[30] “Nemesis,” Oxford Languages

[31] Carrie and Shuler, Women Suffrage and Politics, 5.

[32] Spruill (Wheeler), New Women of the New South, 181; Terborg-Penn, Chapter Ten, in Spruill, ed. One Woman One Vote, Second edition.

[33] Ibid.

Bibliography

Alexander, Adele Logan. Princess of the Hither Isles: A Black Suffragist’s Story from the Jim Crow South. Yale University Press, 2019.

Baker, Jean H., ed. Votes for Women: The Struggle for Suffrage Revisited. Oxford University Press, 2002.

Berkin, Carol. Civil War Wives: The Lives and Times of Angelina Grimké Weld, Varina Howell Davis, and Julia Dent Grant. New York: Vintage Books, 2010.

Catt, Carrie Chapman, and Nettie Rogers Shuler. Women Suffrage and Politics. the Inner Story of the Suffrage Movement. University of Washington Press, 1923.

Dudden, Faye E. Fighting Chance: The Struggle over Woman Suffrage and Black Suffrage in Reconstruction America. Oxford University Press, 2011.

Fowler, Robert Booth. Carrie Catt: Feminist Politician. Northeastern University Press, 1986.

Fuller, Paul E. Laura Clay and the Woman’s Rights Movement. University Press of Kentucky, 1992.

Gatewood, Willard. “The Rollin Sisters: Black Women in Reconstruction South Carolina,” in Marjorie J. Spruill, Valinda Littlefield, and Joan Marie Johnson, eds., South Carolina Women: Their Lives and Times. University of Georgia Press, 2010: 50-67.

Giddings, Paula. Ida. A Sword Among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the Campaign Against Lynching. Amistad, 2008.

Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth. Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina 1896-1920. University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Harley, Sharon, and Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, eds. The Afro-American Woman: Struggles and Images. National University Publications, 1981.

Jones, Martha S. All Bound Up Together: The Woman Question in African American Public Culture, 1830-1900. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Lerner, Gerda. The Grimké Sisters from South Carolina: Pioneers for Women’s Rights and Abolition. University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Newman, Louise Michele. White Women's Rights: The Radical Origins of Feminism in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Spruill, Marjorie J. One Woman One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement. NewSage Press, First edition 1995, Second edition 2020.

Spruill (Wheeler), Marjorie. New Women of the New South: The Leaders of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the Southern States. Oxford University Press, 1993.

———. Votes for Women!: The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee, the South, and the Nation. University of Tennessee Press, 1995.

---------. Hagar. By Mary Johnston. Edited with an Introduction by Marjorie Spruill (Wheeler). University Press of Virginia, 1994.

Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn. African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote: 1850-1920. Indiana University Press, 1998.

Weiss, Elaine F. The Woman's Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote, New York: Penguin/Random House, 2019.

Wilson, Charles Reagan. Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865-1920. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1980.

Yellin, Carol Lynn, and Janann Sherman. The Perfect 36: Tennessee Delivers Woman Suffrage. Edited by Ilene J Cornwell. Iris Press, 1998.

Last updated: December 14, 2020