Part of a series of articles titled The 15th and 19th Amendments go Underground: The Antislavery Movement and Voting Rights .

Article

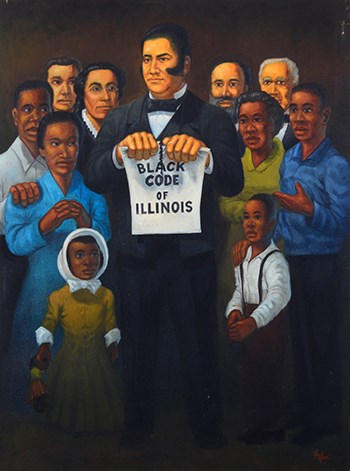

The “Right Man in the Right Place”: John Jones and the Early African American Struggle for Civil Rights

2020 marks the 150th anniversary of the 15th Amendment, which granted black men the vote. However, prominent African American leaders, like John Jones, had begun the struggle for civil rights, including the right to vote, long before the passage of amendment. Although lesser known than some of his contemporaries, his work is no less important.

Courtesy of Illinois State Museum, Illinois Legacy Collection

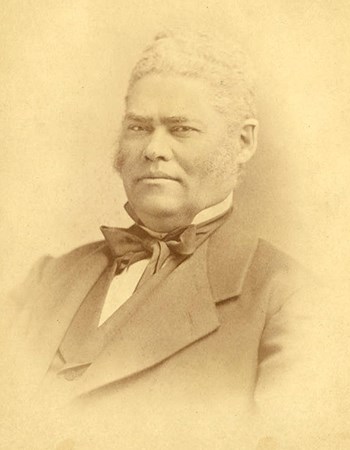

Courtesy of Illinois State Museum, Illinois Legacy Collection

“The Naturalization Bill,” The Chicago Tribune, 26 January 1866.

Courtesy of Chicago History Museum

Note: In 1871, Jones was elected as Cook County Commissioner, and is believed to be the first African American to be elected to public office in the State of Illinois.

Dennis Naglich who authored this article, was an Archaeologist with the Illinois State Museum Collection Center in Springfield, Illinois. Sadly, he passed away on April 6, 2020.

Last updated: August 28, 2020