Last updated: October 18, 2020

Article

James R. Garfield, Gentleman from Mentor (Part I): Founding Mentor Library

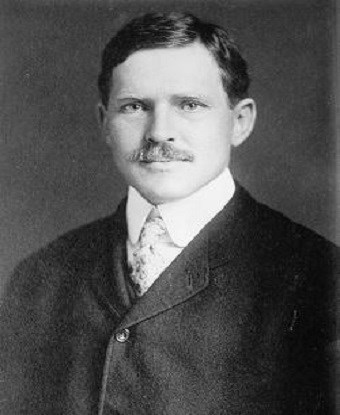

Public domain photo from Wikipedia

“You will certainly have to come home and watch your husband – else our pockets will be very empty. Last night the Library Reception was a great success.”

It was April 25, 1891.

“… A cake was put up at auction & I modestly bid 17 cents, then 19, then 25. Mr. Guilliford [sic] & I found ourselves rival bidders and after a good deal of laughter & fun I got the cake for eleven dollars. I was obliged to give a note for $10 as I only had one with me. Mr. Guilliford endorsed the note as the auctioneer demanded security. Mr. Guilliford then said he would give the Library his highest of $10, so as you see the Board gets $21 for the cake.”[1]

James R. Garfield, the second son of President James A. Garfield and Lucretia Garfield, composed this amusing anecdote. His correspondent was his wife, Helen Newell Garfield. For the better part of the previous two years, the younger Garfield had been pursuing the goal of establishing a “free” public library in Mentor, Ohio, his home town.

For residents of Mentor, the establishment of the library is a notable part of local history. Garfield’s involvement in organizing a new, more widely available library was stimulated by his “vision of making Mentor a model village.”[2] He had only recently been elected to the village council, all of twenty-three years old. That’s not surprising. His father had been President of the United States, and his mother, still living on the farm, was a respected member of the community.

Garfield family photo

Lucretia’s second son, like his brothers, had been educated at elite New England schools. He was trained in the law to serve clients honestly and capably. He had just formed a partnership with his older brother, Hal, and he had recently been elected to the town council. Soon after, he sought to bring into being a “free” library for Mentor. The idea had support in the community.

He believed that it was imperative to attract “good men” to all levels of government. Garfield is a perfect example of the “gentleman reformer” of the late 19th Century. He faced challenges, though.

First, Garfield regretted that the women of Mentor had no vote in the affairs of the community. He wanted to change that. Then there was a political tempest in a teapot over a new Mentor postmaster. Finally, even though many people agreed with Garfield, not everyone did. This last was especially disappointing to James R. because it came in part from unexpected quarters – one of his neighbors, a man who’d been a friend to his father. E. T. C. Aldrich been an enthusiastic, close-at-hand chronicler of James A. Garfield’s 1880 front porch campaign. In 1889, though, he thought the “free” library idea was wasted effort. It had been tried before. It had not come to anything then. It wouldn’t come to anything now. He was not alone in his belief.

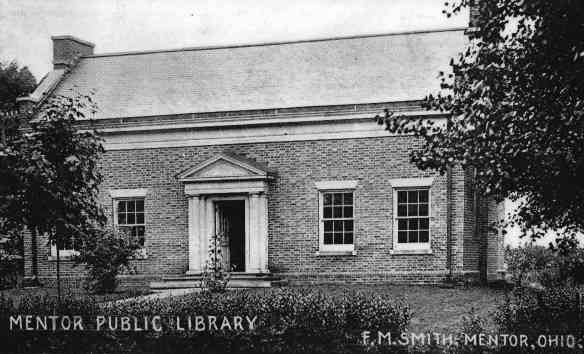

Mentor Public Library

Meanwhile, Mentor’s political establishment was in a state of turmoil. A local political plum was up for grabs now that a Republican had replaced a Democrat in the White House. Local supporters of Republican President Benjamin Harrison wanted to replace the Democratic postmaster, James Angier, with a Republican postmaster.

It was just this sort of patronage brouhaha that left Garfield cold, causing him to confide to Helen that it was “not at all astonishing that decent men dislike to engage in Municipal affairs and yet their doing so is the only remedy for present evils and corruptions.”[4] Though a bona fide Republican, he supported the retention Mr. Angier because he had proven to be an efficient public servant.

The postmaster tumult left little room in early 1889 for any discussion of a replacement for the subscription library that had come and gone, and come and gone again. Discussion that did occur met with some opposition from at least the male members of the village, as represented by Mr. Aldrich.

This last reality led James R. Garfield to favor the political participation of the women of Mentor. He mentioned this idea to Helen in a June letter in which he urged, “If we can excite the interest of the women I feel sure our plans will succeed. I shall advocate giving them the privilege of voting of voting on all town affairs: this stand may still further increase the Republicans against me as many of them think Womens [sic] Rights nonsense.”[5]

A month later, Garfield reintroduced the topic. “Tonight the Council meets,” he wrote on July 13. “One of the new features I wish to introduce is imposing the duty of voting upon women. This will probably meet with opposition.” Looking for Helen’s support, he wrote, “Do you not think that women should take an active interest in municipal affairs? I have always been prejudiced against the idea but I have no good idea for the prejudice – in fact every reason favors putting women on an equal stand with men.” He thought it would be a good experiment. “Why not try it in municipal affairs. Experience, here as elsewhere, will show the faults and advantages of such a change.”[6] Whether the women of Mentor were allowed to vote for the new library system is unknown at this time. Still, it interests this writer that young Garfield was willing to take that step, going against local sentiment as it did.

NPS/Alan Gephardt

He proposed a monthly series of entertainments, “each time presenting something of general interest to the people.” Money for the library was raised from the sales of refreshments. Ice cream, cakes, tea and coffee, and strawberries were favored by one and all. From the records, it is known that many of the Garfields were involved the in entertainments and fundraising of books. Lucretia donated money and books. The piano she purchased played a vital role in the programs of Mozart and Schubert that were conducted at the village hall to raise funds.

Garfield’s aunt and uncle, Joe and Lide Rudolph, served refreshments after many such entertainments. Sister Mollie Garfield Stanley-Brown performed musical duets with a family friend, and directed a melodrama in 1890 entitled “The Sleeping Car.”[8] (It was one of the most successful of the fundraisers.) Mollie’s husband, Joe, a Yale-trained geologist, gave lectures on his experiences in the Alaska territory. Before long, yet one more family member would join the enterprise, but… read on.

The Mentor library was not simply a Garfield project effort, however. In addition to Mr. David E. Gulliford, whose competition with James over a cake introduced this article, the Mentor Postmaster, James Angier, and his wife, Mina Corning Angier,[9] were also involved. Several individuals, whose family names appear on street signs throughout today’s city, were on the library board. These include Harry and Nettie King, Turhand and Sarah Hart, and Mr. and Mrs. John Tyler. Jesse Healy Morley and his wife, Lucy, shared in the task, though they are better remembered for the library in Painesville, established in 1899, that bears their name.

Two final notes complete this writing. Note one: Prior to the free library, books could be taken from the subscription library which was located in what is today the Corning-White House on Mentor Avenue. It’s just a stone’s throw away from James A. Garfield National Historic Site and the current Mentor Public Library.

Note two: James’ youngest brother, Abram, made the most “concrete” contribution of any family member. A trained architect, he designed the original “library and reading room” building, a brick and mortar structure in the Federal style. It opened in 1903 at the corner of Center Street and Mentor Avenue, at the very center of the village and the center of the township.[10]

For nearly forty years, James R. Garfield was the president of the Mentor Library board. The improvement to the community that he championed has stood the test of time. The Mentor free library remains an important cultural institution, meeting place, and repository for the reading community to the present day.

Written by Alan Gephardt, Park Ranger, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, June 2019 for the Garfield Observer.

[1] James R. Garfield to Helen Newell Garfield, April 25, 1891, MS 4571, Western Reserve Historical Society

[2] Thompson, Jack M. James R. Garfield: The Career of a Rooseveltian Republican, 1890-1916, p. 17

[3] Joseph Stanley-Brown to Lucretia Garfield, September [?], 1883, Library of Congress, Garfield Papers

[4] James R. Garfield to Helen Newell, March 27, 1890, MS 4571, Western Reserve Historical Society.

[5] Ibid., June 19, 1889

[6] Ibid, July 13, 1889

[7] Ibid, June 10, 1889

[8] Verdabelle Abbott Spaulding, “A History of the Two Public Libraries in Mentor, Ohio,” unpublished Master’s Thesis, School of Library Science, Western Reserve University, 1950, p.20.

[9] Ibid., p. 14.

[10] Presently, it houses the Confectionary Cupboard at the intersection of Center Street and Nowlen Avenue.