Part of a series of articles titled History & Culture in the Badlands.

Next: The Dawes Act

Article

NPS Photo

NPS Photo

The Homestead Acts were laws issued by the US government to promote expansion into the American West by giving away land. In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the first Homesteading Act into law. Under this initial law, a US citizen could claim a 160-acre plot of public land in the West by filing an application, living on and improving the land for a minimum of five years, and filing for a deed within seven years.

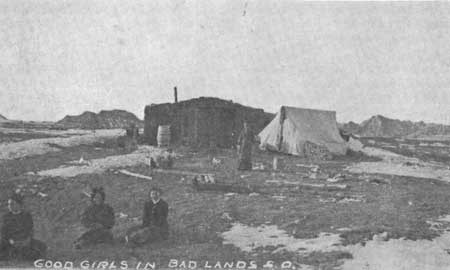

Although the Homestead Act was promising for many individuals, homesteaders soon realized how difficult it would be to settle a claim. It was risky to move out to a homestead without knowing whether the soil would be fertile or the rain would be plentiful that year. Some lower quality plots were cut off from rivers, which made irrigation a challenge. Homesteading also meant living a life of solitude in remote locations across the Great Plains.

Later acts and amendments were passed to make homesteading easier. One example is the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909, which promised an additional 160 acres (for a total of 320 acres) to farmers willing to claim more marginal lands in the Great Plains where irrigation was particularly difficult. An important act for Western South Dakota, where Badlands National Park is located, was the Stock Raising Homestead Act of 1916. This act promised a total of 640 acres of public land for ranching purposes. Many plots around the Badlands were not fertile enough for agriculture but could support ranching operations.

While the Homesteading Acts offered land to settlers for “free,” this “free” land came at a great cost to Native Americans. Much of the land offered for homesteading was seized from the Native Americans who previously inhabited the Great Plains. This was accomplished through legislation like the Dawes Act. Through the Dawes Act, Native Americans who did not comply with government divisions of their land were pushed off of it.

NPS Photo

There were a few requirements to claim land under the Homestead Act. The claim-maker had to be a US citizen, be at least 21 years old, be single or the head of a household, and never have borne arms against the US. Homesteaders could be male or female as long as they met these requirements.

There were also no racial requirements to claim land, which meant that after the 1866 Civil Rights Act, African Americans gained citizenship and thus gained the right to homestead. Although many of the physical structures of African American homesteading have disappeared, there were several communities of Black homesteaders in the mid- to late-1800s. One of them was the Sully County Colored Colony in Sully County, South Dakota – about 160 miles away from the Badlands. In addition to African Americans, many global ethnic groups came to settle in the Dakotas after gaining US citizenship. South Dakota was homesteaded by people from Germany, Norway, Sweden, Poland, and many other countries.

NPS Photo

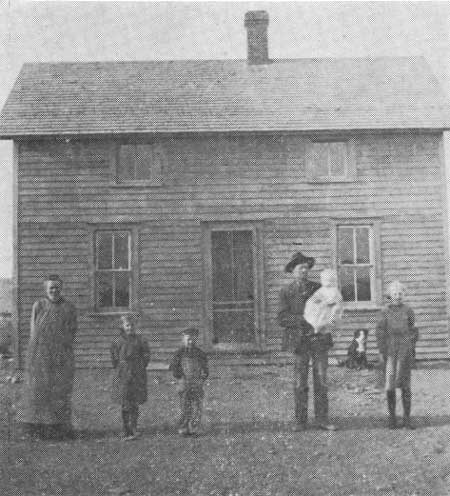

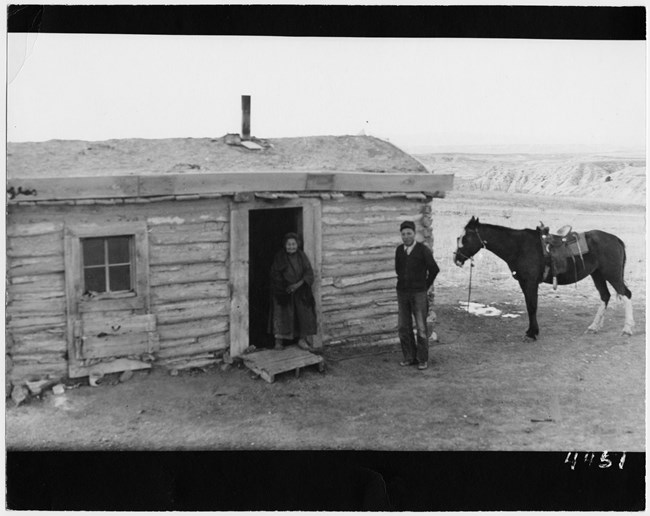

Many homesteaders lived in sod houses – homes made out of the soil surrounding them. Homesteaders packed this soil into bricks to gradually build a home; the sod house had to be at least 12 feet by 14 feet to satisfy the conditions of the Homestead Acts and realize the claim. These were crude shelters and homesteaders would replace them with permanent wood-frame homes as soon as they had the ability to do so.

The daily work of homesteaders depended on what their land allowed them to do. If it was fertile enough, agricultural land meant lots of farming for homesteaders. These farmers would use plows to churn up the soil and plant their crops. If the land wasn’t fertile enough to grow crops but was large enough to support livestock, a homesteader’s day would lean more towards ranching. A homesteader running a ranch would spend their day in the saddle moving cattle, fixing fence posts, and distributing hay. Many homesteaders kept at least a few cows, hogs, chickens, or turkeys for food.

Homesteading was an important part of settling the West. The promise of free land and economic opportunity brought thousands of US citizens to South Dakota. Along with this increased population would come statehood, which endowed additional rights to South Dakota and its inhabitants.

About 40% of homesteaders “proved up” on their claims, meaning that they satisfied the requirements to own their claim. Some homesteaders then sold their property at a profit, but many stayed and became the first of many generations to farm and ranch on their land. Many South Dakotan ranchers today are a part of this legacy, living and working on the land which their ancestors homesteaded generations ago.

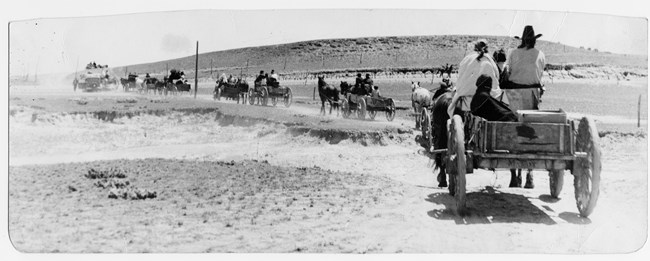

NPS Photo

Homesteading in the Badlands region was slow due to the infertility of its soils. In the early 1900s, two factors came together which brought homesteaders to the Badlands: innovations in transportation and the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909. The Chicago and Northwestern Railway Company built the first train line through Interior (the town directly South of the Badlands) in 1907, enabling homesteaders to access the region like never before. The Enlarged Homestead Act then granted 320 acres (double the acreage that the original Homesteading Act promised) to settlers, making the Badlands an even more attractive option.

While these factors brought the first homesteaders to the Badlands region, later amendments and additions would increase the population significantly. In 1912, the time requirement for living on the land to claim the deed was reduced from five years to three years. This reduction combined with the Stock-Raising Homestead Act of 1916 (which provided a 640-acre homestead on lands officially designated as nonirrigable lands) brought even more homesteaders into the region.

Part of a series of articles titled History & Culture in the Badlands.

Next: The Dawes Act

Last updated: December 22, 2020