Last updated: January 13, 2023

Article

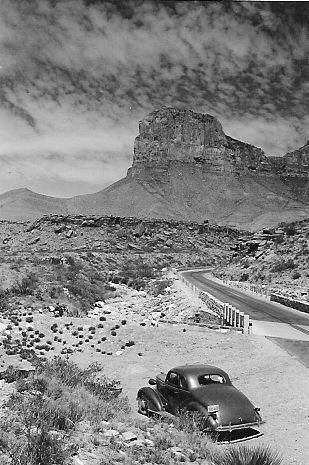

Where We're Going, We Don't Need Roads

One of the most frequently asked questions at Guadalupe Mountains National Park is “Is there a scenic drive I can take to explore the park?” The answer to that question reflects the history of the National Park Service and changing perspectives on visitor access, preservation, and life in the Chihuahuan Desert.

NPS

The First Roads in the National Parks

The Guadalupe Mountains are one of the four sacred mountain ranges of the Mescalero Apache. As a largely nomadic culture, they moved freely across the region across West Texas and New Mexico before the arrival of Europeans and later Mexicans and Americans. While they did not build formal roads in the modern sense, the Mescalero did follow well established paths following the contours of the land and water.

After the American annexation of Texas and Mexican American War, the United States began exploring paths for a potential transcontinental railroad. Army and railroad surveyors entered the Guadalupe Mountains to see if Guadalupe Pass would be a suitable route. While they ultimately decided that the Southern Pacific Railroad would pass further south, closer to the Rio Grande, John Butterfield did see Guadalupe Pass as a viable option for a road route. In 1858, the Butterfield Overland Mail Company established the first “road” in what would later become Guadalupe Mountains National Park. The Butterfield Overland Trail was short-lived in the Guadalupe Mountains – in 1859 the route shifted further south. However, the old path through Guadalupe Pass would become well-trodden by ranchers, hunters, Mescalero, geologists, and eventually – park visitors.

Getting Started

By the time the National Park Service was established in 1916, numerous national park sites had already been established through Congressional and Executive action. Throughout the 1920s, Americans were falling in love with the automobile. In 1930 there were approximately 23 million cars on America’s roads. To respond to this rapid growth, the Bureau of Public Roads began to develop a national road system, and the national parks were poised to be the prime benefactors. In 1924, Director of the National Park Service Stephen Mather wrote in his annual report to Congress:

It is not the plan to have the parks gridironed with roads, but in each it is desired to make a good sensible road system so that visitors may have a good chance to enjoy them. At the same time large sections of each park will be kept in a natural wilderness state without piercing feeder roads and will be accessible only by trails by the horseback rider and the hiker. All this has been carefully considered in laying out our road program. Particular attention also will be given to laying out the roads themselves so that they will disturb as little as possible the vegetation, forests, and rocky hillsides through which they are built.

Beginning that same year, Congress began authorization millions of dollars to construct roads in the national parks, and by 1927 nearly 200 miles of road had been built in the parks, with another 1,000 miles surveyed or authorized. Most notable was the Going to the Sun Road in Glacier National Park, which was constructed between 1921 and 1933.

The New Deal Through Mission 66

Beginning in the 1930s, the National Park Service became the beneficiary of a wide variety of New Deal construction projects. Agencies like the Civilian Conservation Corps and Works Progress Administration poured into the national parks and began massive infrastructure projects – including road construction. For example, a CCC camp constructed the road into Bandelier National Monument, as well as the visitor facilities in the canyon. Another example in the southwest is Chiricahua National Monument, where the CCC built the Massai Point Road into the rugged heights of the park. Perhaps the most famous example of 1930s era NPS road construction was the construction of the Blue Ridge Parkway, begun in 1935. In the 1940s and 1950s, road projects created a network of paved and gravel roads across Big Bend National Park.

After World War II, the National Park Service began to prepare for its 50th Anniversary in 1966 with an initiative called Mission 66. Mission 66 was intended to modernize the national parks for the second half of the 20th century. In the post-war period, buoyed by the establishment and expansion of the Interstate system and rapid growth of the American car culture, this meant building roads in the parks. Mission 66 called for the construction of 2,000 miles of additional roads and highways in the national parks by 1966.

NPS

A New Park With a New Vision of Access

By the mid-60s, the political and social landscape regarding park roads and development had begun to change. In 1964, Congress passed the Wilderness Act which, in part, established the precedent that public lands should be managed for the preservation of a primitive sense of place as opposed to visitor access. Around this time, NPS Director George Hartzog was growing concerned that too many visitors at some parks might detract from the experience of visiting the parks, and roads were a core part of this concern. He said:

The automobile as a recreational experience is obsolete, we cannot accommodate automobiles in such numbers and still provide a quality environment for a recreational experience . . . . No more roads will be built or widened until alternatives are explored. We want to give a park experience not a parkway experience…

In 1966, Congress authorized the establishment of Guadalupe Mountains National Park. Planning began for the new park in the same vision that had driven NPS road and visitor access for the previous 50 years. Early plans spelled out potential routes for a road to the top of Guadalupe Peak, as well as a tramway system and lodge in the Bowl. But the authorization of the park was not the creation. The park would be established in a different world than it was authorized.

By the early 1970s, the environmental movement was in full swing. In the spring of 1970, the nation celebrated its first Earth Day. In December of 1970 the Environmental Protection Agency was established to enforce environmental laws. At the same time, the political winds had begun to shift, and massive expenditures on publicly funded projects like park roads were no longer as popular as they had been in previous decades.

In the mountains, some of the local park advocates had their own views about what the park should look like. Noel Kincaid, a ranch foreman in the Guadalupe Mountains who had been a champion of establishing the park, told an El Paso newspaper in 1970, “I would like to see some good foot trails and horse trails in the park. The people who want to visit the Guadalupes, who want to see nature as God made it could hike in or ride in. The litterers and Sunday pleasure seekers, who want a day’s outing in their automobile can go to places where there are roads already. There might be a few who would be too old to hike in but you know I might like to play football too but I recognize that there are some things I cannot do.”

The growing environmental movement, a shifting political landscape, and an evolving view of NPS preservation meant that by the time the park was formally established in September 1972, Guadalupe Mountains National Park would be nearly road-free. This was virtually cemented in 1978, with the Congressional designation of nearly 50,000 acres of Guadalupe Mountains National Park as Federally designated Wilderness, and today 95% of the park is either in Wilderness or in eligible Wilderness.

What If?

Some visitors today are disappointed to learn that they can’t take a scenic drive into the park’s high country. But that almost was the case. Had this park been established in the 1920s, it was quite likely that the Civilian Conservation Corps would have constructed a rugged road into the mountains, creating a scenic drive high into the Permian reef. Or had the park been established in the 1940s or 50s, it would likely have Mission 66 funded scenic loops radiating from its visitor centers. But those things didn’t happen and Guadalupe Mountains National Park reflects the history and values of the environmental and political movements of the 1970s.

Noel Kincaid would approve.

To learn more about the history of roads in the national parks, you can read the NPS Special History Study on History Roads in the National Park System.