Last updated: November 2, 2020

Article

Geology Of Minute Man NHP

The landscape of Minute Man NHP preserves significant events in American history, but the park’s geological history is 600 million years in the making. The geological story of this park has global significance, and played a key role in the outcome of the battle at Concord on April 19th, 1775.

Tectonic History

600 million years ago, there were only two large continents on earth: Gondwana (made up of Africa, Australia, Antarctica, India and South America) and Laurasia (made up of North America, Eurasia and Greenland). Around that time, two volcanic chains formed off the north coast of ancient continent Gondwana. Within these volcanic chains were distinct magma chambers, deep below the earth’s surface.

This magma would solidify to form vast stretches of underground rock at the heart of the two island chains. The older island chain is referred to as the Avalon terrane, and the younger is called the Nashoba terrane.

Due to the forces of plate tectonics, about 500 million years ago, the Nashoba volcanic chain separated from the continent of Gondwana and moved towards the continent of Laurasia, the ancient North American coast.

The Nashoba terrane collided and sutured with ancient North America. About 20 million years later, the Avalon terrane followed and collided with the Nashoba Terrane rocks. This caused the continent to grow larger, and mountains to rise.

NPS photo

Glaciation

Since 200 million years ago, the ground beneath this area has been relatively quiet, with no major tectonic activity occurring. The primary forces at work were those of wind and rain weathering mountains into hills.

The major features of the park that we still see today were sculpted in the Pleistocene Era, better known as the Ice Age. During this period, continental glaciers repeatedly spread southward from the north pole. The last glacier covered about a third of North America.

Human Geology

Minuteman NHP tells the story of its colonial inhabitants, but the land itself has been occupied for over ten thousand years. Archeological evidence in the Concord area attests to early human habitation of the landscape. Rocks from the Bloody Bluff outcrop were crafted into tools that Indigenous people used approximately nine thousand years ago.

The area named Musketaquid would be settled by colonials and renamed Concord beginning in 1635. The patchwork nature of soils in the landscape made it difficult to grow traditional barley crops. As a result, land use followed the suitability of local soils and conditions. Colonists planted corn, apple orchards, and cleared land for livestock in a mosaic pattern dictated by the glacier long ago. Where no crops could be grown due to soil texture, wooded lots were left.

NPS photo

The many rocks found within the soil were used to build stone fences and home foundations. Houses were often built into the sides or on the tops of ridges, such as the ridge running from the Concord town center to Meriam’ corner. Building into a glacial ridge like this offered protection from the wind.

The Concord Fight

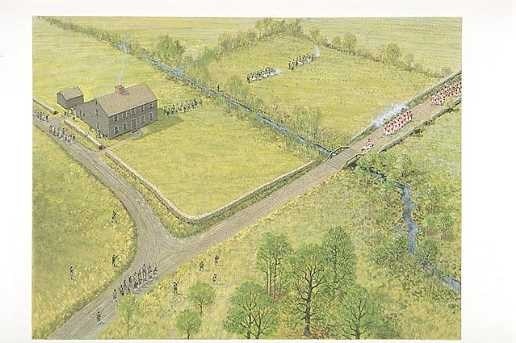

It was atop a glacial hill Punkatasset that the colonists watched smoke rising from the Concord town center, assuming the town in danger. Approximately 95 British Regulars guarded the North Bridge below, and the colonists marched down to meet them, where the first exchange of gunfire of the American Revolution would take place.

The British Regulars’ retreat back to Boston would prove difficult, as the colonists took advantage of the glaciated landscape in this moving battle. The colonists knew the wooded lots, ridgelines, ravines, glacial erratics and manmade structures of their homeland, and used them for cover as they assaulted the line of British soldiers.

NPS photo

After a few hours of quiet, the fighting resumed at the split of the Bay Road and Old Bedford Road, at a site called Meriam’s corner. This was a strategic location to reenter battle because of the shift in topography and a bridge over a small stream caused the column of British soldiers to bottleneck.

The battle continued to a place that would later be dubbed as "Bloody Angle", where the Bay Road turned a sharp corner and rose in elevation among wooded lots to avoid a low-lying wetland area. This is a perfect example of the hummocky nature of post-glacial terraine and how colonial development is dictated by landscape.

Father along in the battle, at Parker’s Revenge site, colonists made a stand from a local hilltop. Recent archeological evidence refutes the earlier idea that the colonials stood atop an exposed bedrock outcrop, and suggests that they used a gentle hill of glacial till instead, which would provide them an egress and cover within the wooded area.

There is no better tie between the geology and history of the park than the story of the park's namesake. Before this land was protected, a boulder became the subject of argument: the land and boulder was sought after for residential development. But this wasn't just any boulder--it was a standing monument. According to local legend, it gave cover to a young Minute Man as he fired shots at British soldiers during the Concord battle. The boulder, later named Minute Man Boulder, would spark a conversation about the preservation of a historical landscape, and what it means to those who visit.

The boulder that provided cover to the early American started its life as the heart of a migrating island chain. Millions of years of weathering and a mile-high glacier carried it to its resting place along the Bay Road of colonial Massachusetts. There, it witnessed the growing tensions of a colony and its mother country. In a single moment, it would shelter a young rebel as he took cover in the first battle of the American Revolution. Almost 200 years later, a new battle would erupt: what to do with the land? Was the Minute Man Boulder worthwhile enough to save from devleopment?

Thanks to the public's interest in preserving cultural heritage, the boulder remains in place, surrounded by over 1,000 acres of protected park land. It is a testament to the area's unique geology, and the colonist's resourcefulness in using it.

NPS photo