Last updated: October 17, 2024

Article

The General von Steuben Statue: Interpreting LGBTQ+ Histories of the Revolution

Transcript

Dave, I'm going to ask you to start us off by talking about the history of the encampment at Valley Forge and the role that General von Steuben played in that history, so that we can begin to understand why a statue was built to mark his memory. David J. Lawrence: I'm glad to. I want to start out by just giving a quick overview about Valley Forge itself and explain where in history it fits within the American Revolution. I think most people listening to this know that this place is connected to the American Revolution, but not necessarily why.

This...the site that I serve at, it was a wintering encampment site or a general encampment site that occurred between two major campaigns in the war. When the army marched in here, it was December 19, 1777. And they stay here for basically six months. They leave June 19, 1778.

So, when they're marching in here, it's been about two and a half years since the beginning of the war with the shots fired at Lexington and Concord.

It's been about a year and a half since the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. It's also been almost a full year since Washington did his famous crossing of the Delaware to attack Trenton and Princeton. When they're marching into Valley Forge, they're marching in here at the very end of what was known as the Philadelphia Campaign of 1777. It was an attempt by the British under General How to capture Philadelphia, which at the time was the largest city in the United States. And the British succeeded.

They defeated the Americans, had several major battles, including, Paoli, Brandywine, Germantown. They captured Fort Mifflin and Fort Mercer along the Delaware. And they were able to occupy the city. Congress had to flee Philadelphia. They're currently settled over in New York. Pennsylvania's rebel government fled the city. Thousands of other Philadelphia residents fled.

Washington, put himself here at Valley Forge because being roughly 17 to 20 miles away from the city borders, they were this army was close enough to the British to keep them bottled up in the city. And to basically keep them from forging at will. And basically keep an eye on them. But also just far away enough, so if the British actually tried to attack them, the Americans could set up pickets and outposts, and be able to see them coming.

While they're here, though, the struggle that they end up facing was less against the British and more of a battle of logistics and organization. While they're here, their supply system absolutely collapses. And they're not getting the food, clothing, and equipment that the men desperately need during those winter months.

And discipline within the army is breaking down. A lot of the men are unfit for duty. The more men unfit for duty means less men working in camp to maintain it. Sanitation fell apart and as a result disease of various sorts typhoid, pneumonia, dysentery, becomes epidemic and deadly. Before this encampment is done, more American soldiers end up dying in this camp than die in any single battle of the American Revolution.

In spite of that, there is a second story to this.

Because the British were stuck in the just as much of it as the Americans, Washington had an opportunity at Valley Forge to enact all sorts of reforms to the army: streamlining the officer corps, improving the supply system, and coming up with a new training system to instill new discipline in the army. So by the time the army leaves the Valley Forge, in spite of all the misery and hardship that they encountered, they actually ended leaving stronger than when they arrived.

And that's actually where one von Steuben comes in because he was an important part of the reformation of his army. Now, von Steuben had been a Captain in the Prussian Army. He had joined the Prussian army from the age of 16. He had already served with distinction during the Seven Years War. He had been wounded twice at the Battle of Prague. And had fairly distinguished military career.

Nevertheless, he was eventually discharged from the Prussian army. And he found himself looking for other places to work, having only a military career. He primarily looked for for fields of military employment. Although he did serve for a period of time as the Grand Marshal for the Prince of a small German province of Hohenzollern-Hechingenn. Forgive me if I've mispronounced that, I'm doing my best.

Eventually he ends up finding himself unemployed in Paris and is offering his services as a military consultant.

It's while he's in Paris that people put them into contact with the American delegation. They're working on an alliance with France, including Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane. [von Steuben] at first refuses, decides not to join the American cause because he thought they had a good opportunity to work for the Margrave of Baden in a similar role. But then a scandal hit. He finds out word from Baden that rumors have been spreading about his sexuality. In particular, during this time, as Grand Marshal for the other prince that he might have been taking liberties with young boys under his charge.

Even if he managed to fight off these charges, that was going to leave a stain on his honor, and severely affected his employment chances in the tight knit community of European nobility. So, he went back to Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane, and said "Hey, remember that job you offered? Hook me up." And he ended up joining the United States.

When he joins the United the United States Army, he joins the Continental Army at Valley Forge in late February when things were kind of at their worst for the army. And he immediately starts to work as Inspector General of the Army in reforming and coming up with a new unified system of drill. That includes a lot of marching, which we tend to highlight. You know, marching and training for battle. But something that I often stress is that most of US soldiers' work is not fighting. It's doing all the other stuff: like building and maintaining decent encampments. And as Valley Forge attested, knowing how to do that was just as important as knowing how to fight on the battlefield.

And if you ever got a chance to look at the drill manual that he completed, a lot of it dealt with the stuff in between the battles. And he's one of the key reasons why this army left in better shape than it arrived. He would serve throughout the rest of the war until 1783 when the Treaty of Paris was signed.

He never went back to Europe. He settled in the United States. He would start by settling at a townhouse in New York City where he lived with various other officers that had served with him as aides to camp. Most notably, a William North and Benjamin Walker, which stayed with him until 1787. He then moved up to a farm, a farmhouse in upstate New York, from land that was granted to him. He would live up there with a butler named John Mulligan. He never married, never had children and remained in close contact with a lot of the officers he served with throughout the war.

And over time, he became he became known as one of the key people for helping to reform and straighten up this army here at Valley Forge.

Dr. Emma Silverman: That's great. Thank you so much, Dave, for this overview of Valley Forge and von Steuben's life.

So, I want to turn now to the monuments in this series. We looked at monuments built between 1832 and 1993.

Yes. Very helpful in your personal Zoom background. Throughout the series, we've learned that monuments often tell us as much about the people who built them and the times in which they were built, as the history that they commemorate.

So the Gentleman Scheuermann statue was dedicated in 1915.

Dr. Emma Silverman: Can you tell us more about its construction? Who commissioned it? Why and who was the artist that created it?

David J. Lawrence: It was designed by a German sculptor named James Jay, although Schweitzer and it was commissioned by the National German American Alliance. And if there was any time in American history where a German American group would want to try to honor German contribution to our nation's founding, it was in nineteenth teen thruout.

Obviously, Germans have been part of America's tapestry and culture from the colonial era. As a matter of fact, at the time of the American Revolution, it's estimated that about a third of all Pennsylvanians spoke German and were of German descent and they have a deep history.

And for most of American history at least among non English speaking immigrants, if anything, Germans were the ethnicity least discriminated against, they will encounter obstacles here and there. But in comparison to, say, Eastern European or Italians or the second wave of immigration in the 19th century, they were generally embraced by American culture.

That is going to change, however, with World War One in 1914. A combination of things [happened] such as the sinking of the Lusitania, the Zimmermann Messaggero with Mexico, and even from the very beginning, most of the English press about the war came via England, and so we were getting a very English centric view of that war. And since England was fighting Germany, Germany did not look all that good. And all of those accounts. And so all of a sudden, Germans were now Huns and they were...it was now...German culture was now considered to be un-American. And many German Americans, who many of whom had had multiple generations of history in America, suddenly found themselves being discriminated against.

If we were to harken back to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, if you remember when we had our little spat with France regarding that war. People started to call French fries "freedom fries." Well, that is a time honored tradition in America, going all the way back to World War One when sauerkraut was suddenly called "liberty cabbage" and frankfurters were being called "liberty sausages." And I mean, even German measles was changed to Liberty measles. I am going to assume German Americans were not fighting too hard over that issue. But considering all the others, it was getting serious. And it actually would culminate with an infamous lynching.

There was a German miner who was actually murdered - and - in a lynch mob as a result of his supposed speaking of anti-American sentiment. The people who committed that lynching were captured and tried and fully exonerated, even though most of them admitted to having done the deed, gives an idea of how Germans were being treated in the United States.

So what better time and what better place for German Americans to demonstrate their patriotism? And some would do it by serving in the military. Some would do it by hanging flags of...American flags of their shops and homes. And in some cases, they would do it by building a statue to a German who helped America win its independence, to again remind people of the German heritage and German culture within America from that time.

And so, yeah, it's the von Steuben statue. von Steuben clearly had a significant contribution to America's founding, but so did a lot of other officers who did not get their statues established at Valley Forge. And one of the reasons his is most notable isn't just because of his personal contributions, but because of what he represented to later German Americans as a symbol of their part in American identity. And ironically, nowadays, of unemployment is being used again by a marginalized group that is trying to use him as a symbol of how they have contributed to American society since the Colonial era.

Dr. Emma Silverman: Yeah, so let's pick it up and speak about that topic a little more. You've done a great job of really concisely giving us that history about how the statue reflects the identity and values of the people who commissioned it.

But how about the ways that members of the public respond today? And in particular, as I mentioned in the opening remarks, we're interested in the ways that visitors to balance Valley Forge's interactions with the monument are shaped by the recent interest in von Steuben as the "gay general" of the Revolution. And then, how does National Park Service interpretation address this topic?

David J. Lawrence: It is interesting. We have begun to get some questions. Most of the time, especially when I've been doing role activities occasionally at the statue around the grand parade ground that the statue surrounds.

When people bring up his sexual identity. First of all, they merely say oh, he is the gay guy. Right? They actually take it in stride. And think of it is just like another interesting tidbit similar to how old he was when he arrived here or, you know, or his background in the Prussian army. You know, it is also interesting because we are we do sometimes have to end up disappointing people in the way we we respond. I think von Steuben is a perfect example of sometimes how difficult it is to try to interpret the sexuality of people back then, especially those who might be deemed homosexual because of they're never going to be out about it.

There was no such thing as coming out. They were you know, there was still a strong social stigma against it. In many cases, it was illegal. And as a result, they're never going to put in writing or letters or correspondence anything that might reflect that. And as a result, we have to parse out through codes, through his affectionate writings to his fellow officers, the fact that he never married and never had children, that he lived much of his life with other men, either in the military and in civilian life.

A couple of his aides de camp would eventually become his heirs. He essentially adopted them in order...so that they could inherit some of his property...and work all of that. But that means also that we have to always add modifiers to what we say. We cannot say that he is gay. We say that it is likely that he was gay or probable that he was gay or that was possible.

But we can never know for sure. And that makes us...basically for a lot of people, that's basically like sitting down between two bar stools. People who are upset of the allegations that he's gay, they want us to fully exonerate him and say, "No, there's definitely no chance." Those who...who are afraid that were intentionally trying to closet him and hide the fact of his identity will be upset that we aren't more adamant about directly expressing his sexuality.

And I think that's going to be a problem that we encounter with other folks who live from that time period and being able to parse out the evidence and express the evidence as best as possible to the public and let the public figure...put together the pieces from there.

- Duration:

- 16 minutes, 13 seconds

In 1915 the National German American Alliance built a statue of General von Steuben in what is now Valley Forge National Historical Park in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania. The monument honored the Prussian-born Revolutionary War General at a moment of rampant anti-German sentiment in the United States. However, in recent years Steuben has been embraced in popular culture for a different aspect of his identity—as the “gay man who saved the American Revolution.”

National Park Service

Valley Forge

Emma Silverman: We'll start with Dave.

Dave, I'm going to ask you to start us off by talking about the history of the encampment at Valley Forge and the role that General von Steuben played in that history, so that we can begin to understand why a statue was built to mark his memory.

David J. Lawrence: I'm glad to. I want to start out by just giving a quick overview about Valley Forge itself and explain where in history it fits within the American Revolution. I think most people listening to this know that this place is connected to the American Revolution, but not necessarily why.

This...the site that I serve at, it was a wintering encampment site or a general encampment site that occurred between two major campaigns in the war. When the army marched in here, it was December 19, 1777. And they stay here for basically six months. They leave June 19, 1778.

National Park Service

So, when they're marching in here, it's been about two and a half years since the beginning of the war with the shots fired at Lexington and Concord.

It's been about a year and a half since the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. It's also been almost a full year since Washington did his famous crossing of the Delaware to attack Trenton and Princeton.

When they're marching into Valley Forge, they're marching in here at the very end of what was known as the Philadelphia Campaign of 1777.

It was an attempt by the British under General Howe to capture Philadelphia, which at the time was the largest city in the United States. And the British succeeded.

National Park Service

They defeated the Americans, had several major battles, including, Paoli, Brandywine, Germantown. They captured Fort Mifflin and Fort Mercer along the Delaware. And they were able to occupy the city.

Congress had to flee Philadelphia. They're currently settled over in New York. Pennsylvania's rebel government fled the city. Thousands of other Philadelphia residents fled.

Washington, put himself here at Valley Forge because being roughly 17 to 20 miles away from the city borders, they were this army was close enough to the British to keep them bottled up in the city.

And to basically keep them from foraging at will. And basically keep an eye on them. But also just far away enough, so if the British actually tried to attack them, the Americans could set up pickets and outposts, and be able to see them coming.

National Park Service

Disease, Discipline, & Death

David J. Lawrence: While they're here, though, the struggle that they end up facing was less against the British and more of a battle of logistics and organization. While they're here, their supply system absolutely collapses. And they're not getting the food, clothing, and equipment that the men desperately need during those winter months.

And discipline within the army is breaking down. A lot of the men are unfit for duty. The more men unfit for duty means less men working in camp to maintain it. Sanitation fell apart and as a result disease of various sorts typhoid, pneumonia, dysentery, becomes epidemic and deadly. Before this encampment is done, more American soldiers end up dying in this camp than die in any single battle of the American Revolution.

In spite of that, there is a second story to this.

Because the British were stuck in the just as much of it as the Americans, Washington had an opportunity at Valley Forge to enact all sorts of reforms to the army: streamlining the officer corps, improving the supply system, and coming up with a new training system to instill new discipline in the army. So by the time the army leaves the Valley Forge, in spite of all the misery and hardship that they encountered, they actually ended leaving stronger than when they arrived.

Yale University Art Library

Military Career of Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben

David J. Lawrence: And that's actually where one von Steuben comes in because he was an important part of the reformation of his army.

Now, von Steuben had been a Captain in the Prussian Army. He had joined the Prussian army from the age of 16.

He had already served with distinction during the Seven Years War. He had been wounded twice at the Battle of Prague. And had fairly distinguished military career.

Nevertheless, he was eventually discharged from the Prussian army. And he found himself looking for other places to work, having only a military career.

He primarily looked for for fields of military employment. Although he did serve for a period of time as the Grand Marshal for the Prince of a small German province of Hohenzollern-Hechingenn. Forgive me if I've mispronounced that, I'm doing my best.

Eventually he ends up finding himself unemployed in Paris and is offering his services as a military consultant.

National Park Service

Recruitment & Scandal

David J. Lawrence: It's while he's in Paris that people put them into contact with the American delegation. They're working on an alliance with France, including Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane. [von Steuben] at first refuses, decides not to join the American cause because he thought they had a good opportunity to work for the Margrave of Baden in a similar role. But then a scandal hit. He finds out word from Baden that rumors have been spreading about his sexuality. In particular, during this time, as Grand Marshal for the other prince that he might have been taking liberties with young boys under his charge.

Even if he managed to fight off these charges, that was going to leave a stain on his honor, and severely affected his employment chances in the tight knit community of European nobility. So, he went back to Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane, and said "Hey, remember that job you offered? Hook me up." And he ended up joining the United States.

National Park Service

Inspector General

David J. Lawrence: When he joins the United the United States Army, he joins the Continental Army at Valley Forge in late February when things were kind of at their worst for the army. And he immediately starts to work as Inspector General of the Army in reforming and coming up with a new unified system of drill. That includes a lot of marching, which we tend to highlight. You know, marching and training for battle.

But something that I often stress is that most of US soldiers' work is not fighting. It's doing all the other stuff: like building and maintaining decent encampments. And as Valley Forge attested, knowing how to do that was just as important as knowing how to fight on the battlefield.

And if you ever got a chance to look at the drill manual that he completed, a lot of it dealt with the stuff in between the battles. And he's one of the key reasons why this army left in better shape than it arrived. He would serve throughout the rest of the war until 1783 when the Treaty of Paris was signed.

National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service

Postwar Life

David J. Lawrence: He never went back to Europe. He settled in the United States. He would start by settling at a townhouse in New York City where he lived with various other officers that had served with him as aides to camp. Most notably, a William North and Benjamin Walker, which stayed with him until 1787. He then moved up to a farm, a farmhouse in upstate New York, from land that was granted to him. He would live up there with a butler named John Mulligan. He never married, never had children and remained in close contact with a lot of the officers he served with throughout the war.

And over time, he became he became known as one of the key people for helping to reform and straighten up this army here at Valley Forge.

Emma Silverman: That's great. Thank you so much, Dave, for this overview of Valley Forge and von Steuben's life.

Brent D. Coons, National Park Service

von Steuben Statue

Emma Silverman: So, I want to turn now to the monuments in this series. We looked at monuments built between 1832 and 1993.

Yes. Very helpful in your personal Zoom background. Throughout the series, we've learned that monuments often tell us as much about the people who built them and the times in which they were built, as the history that they commemorate.

So the Gentleman Scheuermann statue was dedicated in 1915.

Can you tell us more about its construction? Who commissioned it? Why and who was the artist that created it?

David J. Lawrence: It was designed by a German sculptor named James Jay, although Schweitzer and it was commissioned by the National German American Alliance. And if there was any time in American history where a German American group would want to try to honor German contribution to our nation's founding, it was in 1900s teens throughout.

Obviously, Germans have been part of America's tapestry and culture from the colonial era. As a matter of fact, at the time of the American Revolution, it's estimated that about a third of all Pennsylvanians spoke German and were of German descent and they have a deep history.

National Park Service [Image links to an article about WWI at home, including anti-German sentiment.]

WWI & anti-German Sentiment

David J. Lawrence: And for most of American history at least among non English speaking immigrants, if anything, Germans were the ethnicity least discriminated against, they will encounter obstacles here and there.

But in comparison to, say, Eastern European or Italians or the second wave of immigration in the 19th century, they were generally embraced by American culture.

That is going to change, however, with World War One in 1914.

A combination of things [happened] such as the sinking of the Lusitania, the Zimmermann Messaggero with Mexico, and even from the very beginning, most of the English press about the war came via England, and so we were getting a very English centric view of that war.

And since England was fighting Germany, Germany did not look all that good. And all of those accounts.

And so all of a sudden, Germans were now Huns and they were...it was now...German culture was now considered to be un-American.

And many German Americans, who many of whom had had multiple generations of history in America, suddenly found themselves being discriminated against.

National Park Service

David J. Lawrence: If we were to harken back to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, if you remember when we had our little spat with France regarding that war. People started to call French fries "freedom fries."

Well, that is a time honored tradition in America, going all the way back to World War One when sauerkraut was suddenly called "liberty cabbage" and frankfurters were being called "liberty sausages."

And I mean, even German measles was changed to Liberty measles. I am going to assume German Americans were not fighting too hard over that issue.

But considering all the others, it was getting serious. And it actually would culminate with an infamous lynching.

There was a German miner who was actually murdered - and - in a lynch mob as a result of his supposed speaking of anti-American sentiment.

The people who committed that lynching were captured and tried and fully exonerated, even though most of them admitted to having done the deed, gives an idea of how Germans were being treated in the United States.

Thomas A. Foster

Monuments and German-American Patriotism

David J. Lawrence: So what better time and what better place for German Americans to demonstrate their patriotism? And some would do it by serving in the military. Some would do it by hanging flags of...American flags of their shops and homes. And in some cases, they would do it by building a statue to a German who helped America win its independence, to again remind people of the German heritage and German culture within America from that time.

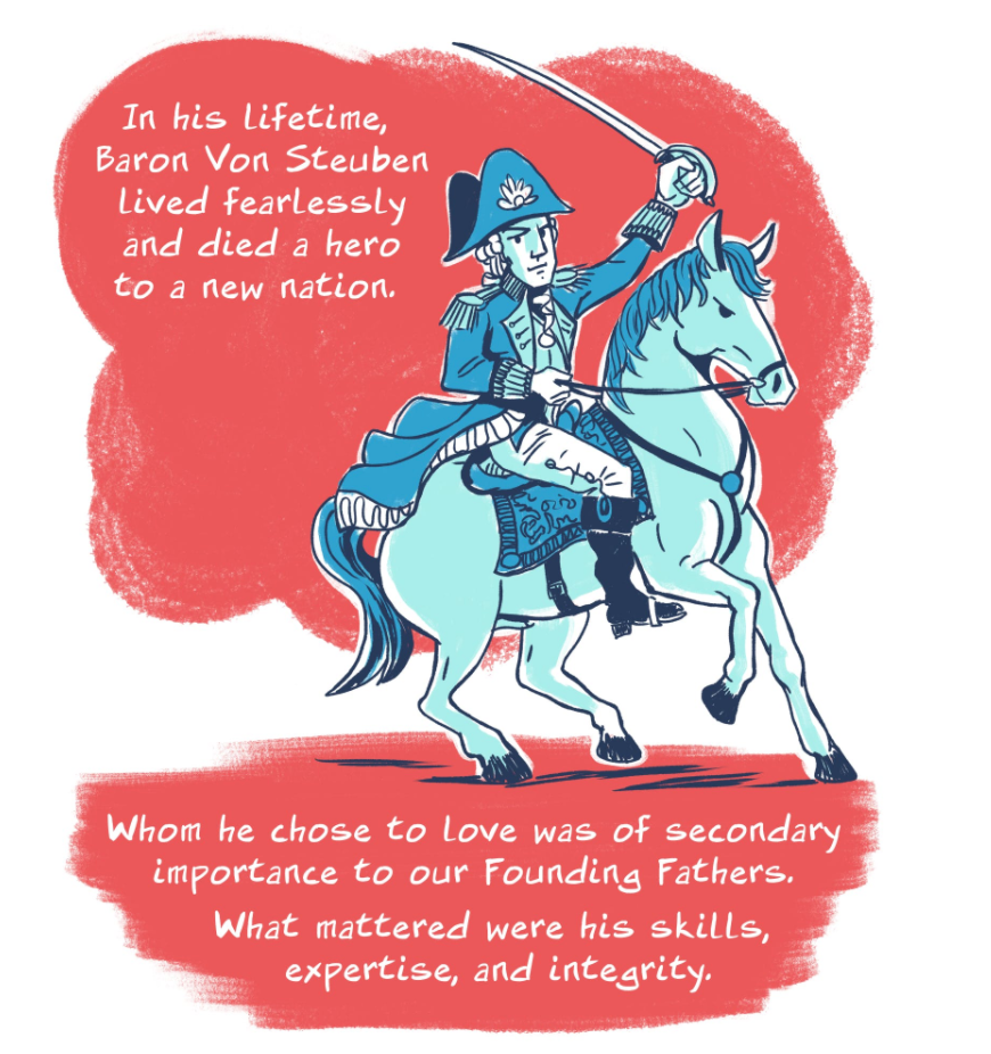

And so, yeah, it's the von Steuben statue. von Steuben clearly had a significant contribution to America's founding, but so did a lot of other officers who did not get their statues established at Valley Forge. And one of the reasons his is most notable isn't just because of his personal contributions, but because of what he represented to later German Americans as a symbol of their part in American identity. And ironically, nowadays, of an employment...is being used again by a marginalized group that is trying to use him as a symbol of how they have contributed to American society since the Colonial era.

National Park Service [Image links to the General von Steuben Monument at Valley Forge National Historical Park.]

von Steuben: LGBTQ+ Figure

Emma Silverman: Yeah, so let's pick it up and speak about that topic a little more. You've done a great job of really concisely giving us that history about how the statue reflects the identity and values of the people who commissioned it.

But how about the ways that members of the public respond today? And in particular, as I mentioned in the opening remarks, we're interested in the ways that visitors to balance Valley Forge's interactions with the monument are shaped by the recent interest in von Steuben as the "gay general" of the Revolution. And then, how does National Park Service interpretation address this topic?

David J. Lawrence: It is interesting. We have begun to get some questions. Most of the time, especially when I've been doing role activities occasionally at the statue around the grand parade ground that the statue surrounds.

When people bring up his sexual identity. First of all, they merely say oh, he is the gay guy. Right? They actually take it in stride. And think of it is just like another interesting tidbit similar to how old he was when he arrived here or, you know, or his background in the Prussian army. You know, it is also interesting because we are we do sometimes have to end up disappointing people in the way we we respond. I think von Steuben is a perfect example of sometimes how difficult it is to try to interpret the sexuality of people back then, especially those who might be deemed homosexual because of they're never going to be out about it.

National Park Service

There was no such thing as coming out. They were you know, there was still a strong social stigma against it. In many cases, it was illegal.

And as a result, they're never going to put in writing or letters or correspondence anything that might reflect that.

And as a result, we have to parse out through codes, through his affectionate writings to his fellow officers, the fact that he never married and never had children, that he lived much of his life with other men, either in the military and in civilian life.

Public Perceptions & History

David J. Lawrence: A couple of his aides de camp would eventually become his heirs. He essentially adopted them in order...so that they could inherit some of his property...and work all of that. But that means also that we have to always add modifiers to what we say. We cannot say that he is gay. We say that it is likely that he was gay or probable that he was gay or that was possible.

But we can never know for sure. And that makes us...basically for a lot of people, that's basically like sitting down between two bar stools. People who are upset of the allegations that he's gay, they want us to fully exonerate him and say, "No, there's definitely no chance." Those who...who are afraid that were intentionally trying to closet him and hide the fact of his identity will be upset that we aren't more adamant about directly expressing his sexuality.

And I think that's going to be a problem that we encounter with other folks who live from that time period and being able to parse out the evidence and express the evidence as best as possible to the public and let the public figure...put together the pieces from there.

Transcript

Tom Foster: Thanks. And you're absolutely right that as historians we are interested in context to best understand his life and what that means. And I'm going to think of myself as standing rather than trying to sit between two bar stools, because that is a great metaphor for being uncomfortable.

And I'm not quite uncomfortable actually at all, now, in terms of this context. There is definitely a queer context for the 18th century in Europe and also in America. And so for von Steuben's context, by the time he comes to Valley Forge there there's generations basically at that point, decades of awareness through publications, popular print media newspapers, and also just urban life. And circulation of individuals.

And in particular, this is occurring across Europe's urban centers. And so it isn't really isolated. It's pretty much across western Europe. And there's probably the most work, at least that I'm familiar with. It's been done on London and there's a fair amount of scholarship that has been written about for, I would actually say decades now also that's been established. So this is probably familiar to a lot of people in the audience already.

If you're interested in pursuing some of the websites that have more information, I would draw you to Rechter Norton's work or the work of Randolph Trumbull is also are both really key individuals. Early on and continuing a lot of the work.

And so in London, if I could talk about Molly Houses, for example, to give us one example that's been mined to really try to understand a significant social and cultural phenomenon that emerges. And this is really in the first half of the 18th century again, were decades prior to Valley Forge. We do see reports. So if I could back up, there's actually something of a morals campaign that's occurring. And you have undercover agents infiltrate these Molly Houses.

The Molly Houses are essentially social clubs, inns, if you will, where men are gathering in something of a --- it's a closed community. A closed circle of friends, essentially. That's why you have these individuals who sort of pose as members and then write up all that they observe. And the writings are really a combination of salacious and entertaining, I think, for some readers. And it mirrors some of the fictional accounts that are also out there about queer sexual in the eighteenth century circulating in the European press. And what I think really significant for us is that you see reports of slang, a common slang that's being used among the members which is really a key sense of some sense of community formation.

You see a sort of cross-dressing. But it's the way it's written about is really theatrical that you have cross dressed individuals performing marriages, performing, and in great detail, like writing about in a very campy theatrical way, childbirths. So, a cross-dressed man who's given birth like a wooden doll, grabbing the others and wailing and carrying on. And so for me, when I read those, there's a real sense also of us and them that's beginning to form.

And one of the things I want to do tonight in my comments is talk about LGBTQ history. But I think the elephant in the room really is heterosexual history. And how are we handling monuments and museums and other sites and problematize that heterosexual history.

So that it is not so unaccommodating or resistant to introducing individuals like von Steuben in other words, our understanding, I think, of the sexual landscape of this time period is problematic. We're still sort of caught up in a romanticized heterosexual model. Then you end up with these individuals that seem anachronistic if we have to spend a lot of time trying to understand them, whereas if we actually started with the right context you may not even need a session on von Steuben, then it would just make sense to people And yet another example of fluidity, maybe gender expression or sexuality.

So what's key about the Molly Houses, though, is in that context, you have this sort of celebratory culture that's emerging, but you have executions that were occurring at the same time. In other words, the individuals that are there writing about this, it's not just for a fun exposé. There is a morals campaign. This is a capital charge. There are men who are being executed at the time for sodomy.

And so it's in that context that you also, I think, can argue for a sense of resistance. But I also think it's a really key context for understanding what that social party if you will, is doing in the face of that context. In other words, it's not in some very welcoming, supportive environment that this is flourishing. So that's the European context for von Steuben.

But in the context of America, we don't see Molly Houses. But what we do know is that, again, for generations. There's been awareness and that's through circulation of print from there are actually newspaper articles about Molly Houses being raided. There are newspaper articles in Boston newspapers about arrests for individuals who are cruising in parks or committing sex acts in parks in London.

And so and you see a level of detail that talks again about slang being used, about specific parks in London named. So there's in some ways also a subversive element to it, and that it is giving voice to and educating Bostonians and other port cities, other Americans about what's emerging, what's possible in life, essentially in urban centres. And it's kind of fascinating to think about that print circulation of information. There's also, of course, a out of circulation of individuals at this time, especially in the port cities. And so you have just circulation of information and knowledge from individuals. And there would still be a handful of examples of court cases, court records, I think, that also draw attention to the issues.

By the time von Steuben, I think what's most common and what gives historians a lot to work with are expressions of love among members of the same sex. And we see this with men and with women. It's a number of sort of high profile individuals Hamilton, as one who exchanges love letters with a close male companion. George Washington is another where you see sometimes these devolve is the wrong word, but spark, I should say, questions about whether or not George Washington was gay. So Larry Kramer has labeled George Washington as gay. So von Steuben is not the only founder in that camp, if you will. And so we do see this.

I do want to sort of name drop a number of books, if people are interested in pursuing this topic of same gender love, which has really become romanticized in the 18th century and through the 19th century. And so those relationships provide cover for individuals. I think it's wrong to assume all of those individuals are gay, to use anachronistic terms. But I think what's important to note is that the society does not look skeptically or concerned at two men who express love and are companions or two women in the same way as they would in the twentieth century. So, in the early twentieth century, that really becomes pathologized and psychologized and is seen as deviant, immoral, wrong, if you will, psychologically disordered.

In von Steuben's time and into the 19th century, there is still a cultural embrace of same gender love. And so again, some of those cases would be individuals who are sexually interested in each other, who are acting on those sexual interests. Some would not be. In fact, I would say the majority would not be. And so there's a number of books that have come out recently about this thinking early on.

Actually, one of the earlier books would be God...Richard Godbee's book Overflowing of Friendship. Thomas Bell Kierski has a new book called Bosom Friends about President James Buchanan as a bachelor and his friend companion William Rufus King. Charity and Sylvia, I think I saw in the chat, is also another wonderful book by Rachel Hope Cleves. Tt's a wonderful read and it explores that lifelong relationship between two women and set up a household and what that means. And Jen Manion's new book, Female Husbands. It's also an excellent study. And so there are a number of books that are sort of expanding out from this world of same gender love to look at transgender expression or gender fluidity, which I think is such a great direction for the work to go in.

We do see this and actually we do see this across class, across race, across gender. So broadly, it's in the culture. Sergio Luciana's work comes to mind. Enslaved men. My Brother Slaves. It's about bonds among enslaved men. I have a chapter in my book, Rethinking Rufus, and bonds among enslaved men. And C. Riley Snorton recent book, Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity would be another one.

So I got sort of the broad context. I'm looking at the clock. So to stop there and turn it back to you, Emma.

Dr. Emma Silverman: Yeah. Thank you so much. And I know you've dropped so many incredible references. And I saw a couple of questions in the chat asking for links to those.

So perhaps after this, I'll get some of the citations from you and we'll send them out to everyone who attended the event tonight. So you all will have those resources if you are able to write them down quickly enough.

But the question I want to follow up. So you've given us a good sense of the, as you said, the sexual landscape that von Steuben is operating in. So he's not an aberration. This is the landscape of gender and sexuality of the time.

I...I'd like you to also speak about not only the actual history of the time, but also the public response that's happening now. So how does this sort of public interest in von Steuben as the Revolutionary War General relate to a longer, persistent interest in the sexuality of the founding fathers? And then can you speculate why is this something that's so interesting to the public that it keeps coming up again and again?

Tom Foster: I've only been zooming for a year and a half. I'm sorry. So I was muted. I am fascinated by this question.

As an early American historian who also is interested in pop culture, I probably about 10 years ago became really interested in how pop culture was depicting early American history.

And certainly even prior to that in the classroom, thinking about how do you use a Disney film like Pocahontas to really sort of explore what themes they are creating anew, what history they're teaching. And when you think about how little the most of the public is exposed to academic articles, for example, I mean, they really circulate among academics. I think you can make an argument that a Disney film like Pocahontas is probably teaching people history more than many other sources.

So I thought, actually it's not just a fun exercise, it's really important. I ended up writing a book called Sex and the Founding Fathers, which you had in the slideshow that traced this long public interest in the personal lives of the founding fathers. And so I think there's six chapters. I've forgotten now at this point.

The cover individuals, including George Washington and Ben Franklin, John Adams and others. And Hamilton. And it looks at how characterizations and things about their personal lives, whether there's infidelity or monogamous marriage or the greatest romance of the American Revolution or the gay general. There's all these sort tropes that come up.

They change over time for the same individual and often it's not because new sources are produced. In other words, it's not because someone found a treasure trove of letters that shed a new side. It's often stuff that just keeps getting research related. But authors tend to emphasize an aspect that they think the readership is going to be interested in at the time. And so you can really map it to a broader narrative of the history of sexuality.

What kinds of things are people embracing from me? In the book, I conclude and I argue that we do this because we're always seeking ways to connect to that founding generation. I mean, they embody the country and the nation. It's a way to really connect to the country and the nation in that way to understand who these individuals are. And they're so far removed from us. We...this is said over and over again. Right? As you work with public history sites, you know, whether it's a statue that's just so unapproachable and cold how do you actually bring that to life and talk about a person? Although I think Dave Lawrence is probably the perfect perfect person to bring a statue to life and make you want to listen to it.

So that I think sex is used in that way. You know, it's very familiar. I should shouldn't be so specific. I would say intimacy or personal lives: love, romance and including sex. That's familiar to people, it seems accessible. The problem is I'm a historian of sexuality. The first place I go is how different intimacy and personal lives and sexuality are now, from the 18th century. It's the last avenue, I would say, to try in terms of trying to access these individuals. I mean, those are completely different worlds.

And if I could just use the example of John and Abigail Adams, we think of them as the greatest romance of the American Revolution or they've been written about in this way. We are able to build that argument based on letters because they're separated. In itself it is interesting that they're separated if they are so intensely in love. And in fact, they're often not separated by an enormous amount of distance. So in some ways, the separation is chosen. It's their chosen mode of being a couple, at least for John Adams.

And if you think about 18th century marriage, the position of women in the late 18th century within marriage, I mean, with coverture laws, women are entirely dependent on husbands. They're not allowed to enter contracts. I think this is also probably familiar to people who can't enter into lawsuits on their own If they're married, if they have a job, their wages are legally belonging to their husband. In the area of intimacy, there is no such thing as sexual assault within marriage. I mean, it is the husband's right to have sexual access. And so there is no consent to sexual intimacy. Is it just sort of a few of the really glaring ways in which it's hard for us to sort of look at an 18th century marriage and the position of women, in particular, in that union and in some way connect with it. It is not our world.

So that's sort of the book in a nutshell.

But there's obviously an entirely different point for von Steuben here that has already been mentioned in terms of him being a gay general. And I think you had really great comments. And I think Dave did also, about the importance of recovering gay history for LGBTQ people. And so then we're into a different level or a different topic really, of representation.

So, I...I'll just add before I wrap this question up, I completely understand the need for recovered histories, for whatever groups are marginalized and left out of dominant narratives That's a wonderful and important exercise. It's a real need for us to understand our histories more broadly, more inclusively .That's desperately needed in this country.

That being said it does bump up against what I was saying earlier about problematizing the sexual landscape in general and broadly, and so that once you actually, if you cement in place terms that are just such shorthand, like he's a gay general, without having problematized the broader landscape I think we're missing an awful lot there, as much as we are capturing something else.

In other words, I understand why it's done politically, and I think it's also very personally important for people, but it is unfortunately bumping up against a broader sort of restructuring that I think is so important for us to understand broadly in early America.

- Duration:

- 17 minutes, 54 seconds

The General von Steuben Statue at Valley Forge National Historical Park and the challenge of interpreting queer history in the Early Republic. Author Thomas Foster explores gender and sexuality in the late 18th and early 19th century and how it differed from LGBTQ experiences through the 20th century and today. He discusses LGBTQ history, romanticized tropes, and how to see interpretation with an inclusive context.

The Library of Congress

Gender & Sexuality in the Early Republic

Emma Silverman: But I want to now turn to Tom for the second half of the presentations to give us some broader context for von Steuben's life and what we know about his sexuality. So, Tom, the contemporary public interest in Steuben's sexual identity is part of a growing awareness and hunger for LGBTQ history that took place before the gay liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s. Can you contextualize what we do know about von Steuben's life by telling us about gender sexuality, and especially about same sex desire in early America?

Thomas Foster: Thanks. And you're absolutely right that as historians we are interested in context to best understand his life and what that means. And I'm going to think of myself as standing rather than trying to sit between two bar stools, because that is a great metaphor for being uncomfortable.

And I'm not quite uncomfortable actually at all, now, in terms of this context. There is definitely a queer context for the 18th century in Europe and also in America. And so for von Steuben's context, by the time he comes to Valley Forge there there's generations basically at that point, decades of awareness through publications, popular print media newspapers, and also just urban life. And circulation of individuals.

And in particular, this is occurring across Europe's urban centers. And so it isn't really isolated. It's pretty much across western Europe. And there's probably the most work, at least that I'm familiar with. It's been done on London and there's a fair amount of scholarship that has been written about for, I would actually say decades now also that's been established. So this is probably familiar to a lot of people in the audience already.

If you're interested in pursuing some of the websites that have more information, I would draw you to Rechter Norton's work or the work of Randolph Trumbull is also are both really key individuals. Early on and continuing a lot of the work.

Molly Houses: Early LGBTQ+ Social Clubs

Thomas Foster: And so in London, if I could talk about Molly Houses, for example, to give us one example that's been mined to really try to understand a significant social and cultural phenomenon that emerges. And this is really in the first half of the 18th century again, were decades prior to Valley Forge. We do see reports. So if I could back up, there's actually something of a morals campaign that's occurring. And you have undercover agents infiltrate these Molly Houses.

The Molly Houses are essentially social clubs, inns, if you will, where men are gathering in something of a --- it's a closed community. A closed circle of friends, essentially. That's why you have these individuals who sort of pose as members and then write up all that they observe. And the writings are really a combination of salacious and entertaining, I think, for some readers. And it mirrors some of the fictional accounts that are also out there about queer sexual in the eighteenth century circulating in the European press. And what I think really significant for us is that you see reports of slang, a common slang that's being used among the members which is really a key sense of some sense of community formation.

You see a sort of cross-dressing. But it's the way it's written about is really theatrical that you have cross dressed individuals performing marriages, performing, and in great detail, like writing about in a very campy theatrical way, childbirths. So, a cross-dressed man who's given birth like a wooden doll, grabbing the others and wailing and carrying on. And so for me, when I read those, there's a real sense also of us and them that's beginning to form.

Problems of Heteronormative History

Thomas Foster: And one of the things I want to do tonight in my comments is talk about LGBTQ history. But I think the elephant in the room really is heterosexual history. And how are we handling monuments and museums and other sites and problematize that heterosexual history.

So that it is not so unaccommodating or resistant to introducing individuals like von Steuben in other words, our understanding, I think, of the sexual landscape of this time period is problematic. We're still sort of caught up in a romanticized heterosexual model. Then you end up with these individuals that seem anachronistic if we have to spend a lot of time trying to understand them, whereas if we actually started with the right context you may not even need a session on von Steuben, then it would just make sense to people as yet another example of fluidity, maybe gender expression or sexuality.

Early LGBTQ+ Culture in America

Thomas Foster: But in the context of America, we don't see Molly Houses. But what we do know is that, again, for generations. There's been awareness and that's through circulation of print from there are actually newspaper articles about Molly Houses being raided. There are newspaper articles in Boston newspapers about arrests for individuals who are cruising in parks or committing sex acts in parks in London.

And so and you see a level of detail that talks again about slang being used, about specific parks in London named. So there's in some ways also a subversive element to it, and that it is giving voice to and educating Bostonians and other port cities, other Americans about what's emerging, what's possible in life, essentially in urban centres. And it's kind of fascinating to think about that print circulation of information. There's also, of course, a out of circulation of individuals at this time, especially in the port cities. And so you have just circulation of information and knowledge from individuals. And there would still be a handful of examples of court cases, court records, I think, that also draw attention to the issues.

So what's key about the Molly Houses, though, is in that context, you have this sort of celebratory culture that's emerging, but you have executions that were occurring at the same time. In other words, the individuals that are there writing about this, it's not just for a fun exposé. There is a morals campaign. This is a capital charge. There are men who are being executed at the time for sodomy.

And so it's in that context that you also, I think, can argue for a sense of resistance. But I also think it's a really key context for understanding what that social party if you will, is doing in the face of that context. In other words, it's not in some very welcoming, supportive environment that this is flourishing. So that's the European context for von Steuben.

Sexual Landscape of the 18th & 19th Century

Thomas Foster: I do want to sort of name drop a number of books, if people are interested in pursuing this topic of same gender love, which has really become romanticized in the 18th century and through the 19th century. And so those relationships provide cover for individuals. I think it's wrong to assume all of those individuals are gay, to use anachronistic terms. But I think what's important to note is that the society does not look skeptically or concerned at two men who express love and are companions or two women in the same way as they would in the twentieth century. So, in the early twentieth century, that really becomes pathologized and psychologized and is seen as deviant, immoral, wrong, if you will, psychologically disordered.

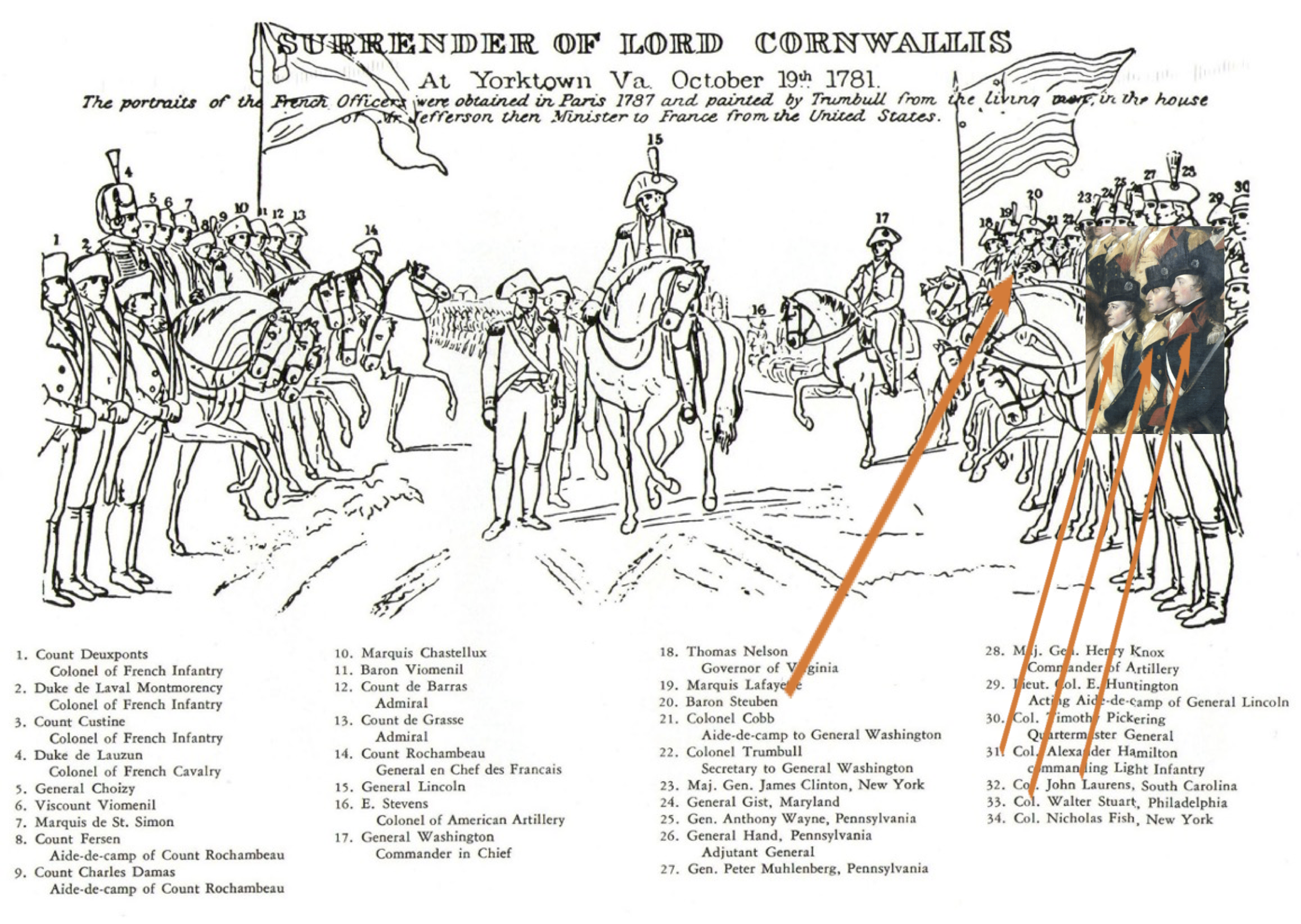

By the time von Steuben, I think what's most common and what gives historians a lot to work with are expressions of love among members of the same sex. And we see this with men and with women. It's a number of sort of high profile individuals Hamilton, as one who exchanges love letters with a close male companion. George Washington is another where you see sometimes these devolve is the wrong word, but spark, I should say, questions about whether or not George Washington was gay. So Larry Kramer has labeled George Washington as gay. So von Steuben is not the only founder in that camp, if you will. And so we do see this.

Transcript

We've gotten some questions already through a Q&A button and the Chat. But I would ask you...we'd love to get some more. So, as we start off this conversation, please do use that Q&A button and send us a couple more. And again, we'll get to as many as we can. And then follow up later if we're not able to get to all the questions.

So my opening query for Dave and Tom, which I think follows really well from what you were saying, Tom, is so we've spoken kind of about the context and we've spoken about the statue

So what are the two of you what are your opinions?

Do you think that LGBTQ history should be part of the National Park Service, its formal interpretation of the General von Steuben statue?

What I mean here is it's not just when people come in kind of happened to mention it. But for a plaque in writing somewhere, somewhere integrated somewhere into that formal interpretation.

And in answering that question, I'd like to hear your thoughts on how we balance what we know about von Steuben's life. What we think about what he might have wanted with what the monuments creators intended.

And then also, again, what is important to contemporary marginalized communities seeking representation in the commemorative landscape?

Dave Lawrence: I'll begin. All right. It's a...it's a lot to try to cover.

I will say that I often find it very difficult, especially in the setting of Valley Forge, should be able to try to incorporate that in simply because so much of our programming interpretation is based more on act actions within the encampment. And there...and the impact on systemic and the institution of the army and the military that was going on here.

We very rarely get an opportunity to get into the social history and the personal history of some of the the key figures that are here. And also we have also been moving away from talking a lot about the officers and doing more of a, you know, rank and file view of the army, including talking about the demographics of the people who made up the army, the women and children and civilian...civilians who would travel with the army.

So now we have to focus our attention back to the personal lives of the officers again, as we as we do that. I think it should be incorporated in some way or another because there's an important part of understanding his identity. However, I think it has to be included with modifiers.

We can state why he...why he might be suspected of being gay, but again, to suggest that he might be out as you know, as blatant has to be he has to be couched properly.

We we can point out, I think the best thing that we could do is use primary sources and talk about the relationship. The lifelong relationship they had, especially with North, but also with Benjamin Walker and, you know, use quotes that they send to each other in their letters.

And I think that would allow that sort of relationship to kind be brought out, you know, basically holistically rather than...the...rather than making it an act of, hey, look, we're trying to appease to the LGBTQ. Instead making it integrate that as part of the natural, you know, expression of von Steuben and the life that he led.

Thomas Foster: I think I would agree with that. I definitely think it's important. But I'm an historian. And if I'm at the grocery store and you had a bag of carrots there. And there was some history that I wanted to talk about, I would.

Say, I just think any opportunity to talk about history is a great opportunity and why would you not want to? For me, it's a missed opportunity if you don't. So then the question is, how do you do it? And I really like the idea. The idea Dave is raising about the context that there's clearly personal lives being talked about for the other individuals related to Valley Forge. And people do want to know about loved ones for the individuals.

Are they writing to loved ones at home? What is that? How do they manage that whole aspect of their lives? Is there...especially if they're head of a household, or want to be head of a household name. It's such an important role for a man. Are their loved ones that could affect their performance basically there also.

So I just think it is relevant, intimate life, personal life, is relevant. And so then therefore, it makes sense to talk about what is known about student von Steuben.

I do think moving away from terms is important. In other words, we don't have enough of a enough of an accurate terminology to use or enough of a shared terminology for all of us as a group to get together, or for strangers to come together in front of a monument and just hear a term like he's a gay general.

You clearly have to talk I think, much more descriptively about what is known about an individual. My concern becomes about the modifiers because I think there's very little evidence about heterosexuality in so many cases. But we are not using modifiers there. So you won't see modifiers about love between George and Martha.

But what's missing there is that we have almost nothing about the love they expressed for each other in written letters and there are no children. They got married. That's pretty thin evidence for a lifelong love, right?

I mean, we know from our own personal relationships, relationships are complicated, really complicated. And I will also throw into this mix: We don't talk about bisexuality or fluidity or that a person's sexuality could change over time.

In other words, we sort of possibly...

Dave Lawrence: Hamilton.

Thomas Foster: Right. We sort of immediately move to terms that we can grasp that are going to be sort neat and nicely contained for us to just sort of get used to.

But I think, again, with those modifiers, I guess I'd like to see them more evenly applied or perhaps not used at all. Perhaps we really just talk about what we know.

Emma Silverman: David, you have a question? You wanted to...see raising your hand?

Dave Lawrence: Yeah. I also want to get into going back to the original sources. One of the issues, especially when parsing out the relationships between the people back then, is I'm and I'm saying this in part because I would like Dr. Foster's opinion on this one.

The one of the things that I often have trouble with when trying to figure out the relationship between folks back then was me trying to put my 21st century idea of both queer culture and normative culture into an 18th century context.

Perfect example would be the things, as you mentioned, the expressions of love that are expressed between various men with within this army are very effusive and there comes a question as to how much of...and was often very rarely question. And that does lead to the question of how, you know, how do you define the filial, maybe platonic love that is being expressed by those statements compared to ones that might be of a more romantic nature?

Because a lot of folks back then would write to one another to close friends with expressions that in modern day parlance would be seen as romantic overtures. If I were to write to a male friend of mine, or a friend of mine to whom I am not romantically connected, that I love until I absolutely adore and love them and cannot wait, wait with bated breath upon our next return. So that they may once again be in my arms. People would consider that to be romantic overtures today, but would not necessarily back in the 18th century.

And I'm wondering with Dr. Foster, as someone who has dove into this era a lot, lot more than I have, how that how he works with parsing that out.

Thomas Foster: It's a real challenge for historians. I will say. And it becomes a really central question like what is your burden of proof then to say someone is involved in a same sex sexual relationship, or an intimate relationship?

Historians for the most part, for heterosexual relationships, rely on birth records. If there's a child that happened, then we know the individuals had sex, or again, a marriage certificate. And that's really sort of the hard evidence that we rely on. But honestly, in the background with the hardest evidence is just the default that that historical individuals are presumed to be heterosexual. Unless we have clear evidence, clear evidence, to argue otherwise. For the most part, that it seems to be a problem of how we approach history.

So some of those expressions of love, I think, again, you have to really contextualize them with what you know about the individuals and maybe what all the other letters say. Perhaps it's very hard to know. And you end up in the realm of biography You end up in the realm of individuals in their heads. I mean, these are really complicated things. Motives are really hard for historians to get at.

And so I just think it's we don't have really neat answers here, unfortunately. I do think it's worth noting that some of those letters where they do talk about love also use references to physical intimacy. So long to hold you in my arms or curl up and sleep with you, miss you in my bed, those kinds of things.

There are even I think in Hamilton's letters with Lawrence, there are references to, I think, a bedpost which sort of in the way that it's written about it, it's clearly a phallic reference. I think that's what Hamilton...may be with others. But this is an example of the sort of like in other words, a range that's being expressed within this genre of expressing oneself, if you will. And so it ends up being where the historians find what they think is the truth about those individuals.

Emma Silverman: I have a question about sources that I wanted to bring into this conversation. She asks. "This conversation raises so many questions about the expansive suite of source material available to interpret the past written public documents folklore stories, past structures and landscapes, fashion, artistic renderings, etc. and the different frameworks we might use and questions we might ask to draw meaning from these? How might we rethink or reconsider source credibility, apply new types of questions, and/or draw satisfaction from open ended or unresolved findings, so as to bring under-voiced stories to the center?"

Do either of you have thoughts about...We've been talking about letters. You spoke about the newspaper articles a bit, Tom. But this question of sources is again, if we don't...it's often about all people's personal, intimate lives. We have the marriage and birth certificates as the hard evidence. And then we have this other range of sources. How important are sources? And can they help us maybe be more open ended in our findings? Not having to draw one-to-one parallels with contemporary identities. But maybe draw something more fluid or open ended?

Thomas Foster: I think we have to be more open ended ultimately. But was there a question about what sources are available for this type of study?

Emma Silverman: I think I think that would be helpful to hear. And then Lysa was also asking, you know...what, "Are their sources that aren't...don't seem as credible, maybe like oral traditions?"

Or something that's not like a state document that looking from that sometimes looking at sources that are not so official actually helps bring marginalized voices to the fore. So, I think her question was about that in relationship to this.

Thomas Foster: I think the...great. I mean, it's really almost a question of methodology. It's part of it is at least. And I do think there's been such great work about using even official records, to read, if you can, read against the grain to understand what is being said in there, that it is sometimes in opposition to the official.

In other words, the official record is produced for a reason to perpetuate the official in power. But there are also all sorts of ways to read about what is going on on the ground. What was this individual doing? What what are they expressing? Reading those sources against the grain, I think can be very helpful.

I, I often, at least in intro classes, hear from students that they're concerned about sources with bias. Look, for me, bias is often what's most interesting to an historian. So in terms of how you evaluate a source, it comes down to I think the audience is probably quite familiar with this, your claims.

And so you can make certain claims about a fiction fictional account that has the queer scene between two individuals could be written about in terms of spread of information and knowledge about this.

Thomas Foster: Right. So that could be the claim. That's a clear claim. You have this published circulates understanding and awareness of it. That's fine. And your claim there, once you start talking about that, this is evidence of individuals actually engaging in the activity, then you need a source that actually would talk about the individuals.

So I'm not sure I've gone off the question, but hopefully that speaks to it somewhat.

And I do want to say about sources I saw in the chat, also a reference to Jonathan Katsas. He has these great early volumes, I think they're from the seventies or nineteen eighty even really early on a pioneer in American history.

There are two massive volumes that are collections of documents. And so that's...a...and there are all sorts of documents. I mean, what's interesting about doing LGBTQ history in a time period that people think LGBTQ history didn't really exist is you do see it in just about every type of source, court records, newspaper personal letters, et cetera.

Emma Silverman: Dave, I know we have a we do actually have and we're talking about histories that where you have to sort of read between the lines. But we do actually have an official record of LGBTQ history at Valley Forge? Do you want to talk about that a little bit?

Dave Lawrence: But yeah, actually, it was...I know this it was brought up in the chat and at the looks, and it's a good reminder also of the consequences of being outed in that time period. Even if things might occasionally be suspected. It was always a wink and a nod and never outright stating.

There was actually a Court-Martial that occurred at Valley Forge. Lieutenant Frederick Enslin was was charged with sodomy, attempted sodomy of a soldier under his command, and was ordered to be discharged. As Washington said, "with infamy" from the Army. And if I can, I have a copy of the general orders that marched it.

"His Excellency, General Washington approves the sentence with abhorrence and detestation at such infamous crimes and orders Lieutenant Enslin to be drummed out of the camp tomorrow morning by all the drummers fifers in the army never to return."

That he made sure that ge included in his General Orders, his personal feelings on the matter. But it is also interesting to know that the guy was court martialed and drummed out of camp. Concerns that sometimes sodomy could be considered a capital crime. Clearly was not the case within this army, but that was occurring...that... that court martial occurred in March. Right at the same time that von Steuben is beginning to start training and drilling the men.

And there has been actually a running question about whether or not Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane in Europe or in Washington and other senior officers in America knew anything about the scandals that von Steuben was leaving behind when he arrived here. I tend to think that maybe Franklin might have been keen to it because he was always up on the scuttlebutt about going on in French...in the...in the European courts.

But Washington very likely was not, or that the very least turned a blind, blind eye to any any suggestions. And I think that court martial is a perfect example of it. And a perfect example, again, of why someone like von Steuben would still need to be very circumspect and very coded in his language. You know, in that era, in that society.

Emma Silverman: You know, we got a question related to that from Robert, a pre-submitted question asking, "As a high status man, one striving sexuality, possibly was an open secret, understood or at least rumored about? Any information?"

And so I think that question speaks to the question of what was the flow of information about von Steuben? Even if we know. And also, how did class and other forms of identity affect how sexuality was read or policed in the time period?

Dave Lawrence: I would I cannot speak with authority on this. I'm going to probably punt this over to Dr. Foster.

I will say, though, that it, it is very similar to other ideas of class. When somebody is doing something that is considered away from what was considered social norms, if you are poor you are ostracized for it. If you are rich, you are considered eccentric.

And I'm willing...I'm thinking that it was probably similar in this day and age...for...for...for von Steuben's behavior. But I can't say for sure or with authority. So I will pass on to Dr. Foster.

Thomas Foster: I mean, I would agree with you on that point. I think class plays a role in a few ways here. You could provide cover it certainly for elites would just provide more opportunity for them to have private unobserved time. Or some sort of privacy, essentially. Are a measure of that. I do think elites could be subjected to policing, though, certainly if there's a morals campaign.

We do see, though, I think obviously, that elites would have much more leeway than non-elites. That being said, for class segregated world, non-elites, are also going to have opportunity if they are away from interaction or closely watched by elite. They would, however, be much more subject to policing by elites. And you see this in a whole host of contexts.

You would see this not only with not elites, but with dependents, servants. In the colonial context, you have cases where indigenous individuals engaged in same sex behavior are being policed as part of the colonial project, as part of bringing a different moral structure, and trying to overlay it and impose it on that society as colonial subjects. So I think there's a whole host of ways that we need to think about how class is playing a role here. But there's probably not a really simple way to just say that one group is allowed in one class and not the other.

I do want to add, however, that the elites seem to fall under more emasculating satire. For example, for first or suspect same sex socializing. And so you do see there were all those images of the Macaronis in the slideshow. It's sort of an example of an 18th century fop that is suspect. They are a queer character in that they have this kind of deviant same sex, social, and suggestive sexual world. They clearly dress in the manner and act in a manner that's effeminate. So the the awareness of same gender, sexuality, and intimacy is so prevalent in the culture that you can actually use it to emasculate men in in tropes that are somewhat cryptic.

And you see that in Europe. You see even in the colonies and certainly in the time of the Revolution.

Emma Silverman: And for those I know, we're making reference to the PowerPoint. If you joined us right at 6:00PM, you didn't show up ten minutes early for that. We will be playing it again at the end of the event.

So you can watch it with fresh eyes or you see it for the first time. And take a look at some of these images that are being referenced I wanted to return to that question.

We've touched on it a bit, but we've been speaking to the complexity of interpreting personal lives and intimacy in this time period and terms that read today and are even politically important today. So what do you all think about Matthew's question about the language or semantics to use?

I think both you have, and I, well, sort of a resistance to a very easy label like the "gay general." On the other hand, when I think about that webcomic, it ends with a sort of a plea for us to honor the contributions of LGBTQ service people to the nation.

In other words, von Steuben is being called the "gay general," in part to to talk about why queer people today should have rights and should be able to serve in the army. And so on. And so I just I guess, again, I'm coming into that sort of conundrum.

What I'm hoping you could speak to it just in terms of language. So if really practically if we're talking about the personal lives and intimacies of figures at Valley Forge, including von Steuben, then in some way, in relationship to the monument, what kind of language is actually being used in that interpretation?

Thomas Foster: It's a I think I mentioned this briefly earlier on, so I won't. I'll give Dave some time to talk about if he wants to. But I do think I agree with you. It's really hard to find shorthand terms that are going to really accurately capture for everybody what's going.

I do think it's I think what you're doing is really wonderful that you're having a series like this on monuments, but then that you would have a particular one to really do a much deeper dive to talk about all the issues here is what's needed.

And in the actual site, I just would hope there, you would have the discussion, the conversation, the fuller information provided. I think that's key.

I'm seeing in the chat some really important things that should also, I would think, be mobilized in that context. So that if a reference was made to the fact that others have referred to him as the "gay general," in other words, that's another way of doing it then. You don't have to own it then. You could say this is occurring, which I think is what you are doing.

But then you might also include some of this historical context that's so important. LGBTQ individuals have not been allowed to serve openly in the military until very recently. And so it just gives you, I think, another window into how important it is to be having this conversation and in a place that is like Valley Forge and so important to the founding and really to our understanding of patriotism. I think those are really important things to be accomplishing.

And there's another comment here that it's not that far back that LGBTQ individuals would not be allowed to work in the NPS. Right?

And that would...be...because they were fired in droves, LGBTQ people from the federal government. I think that's what that is a reference to. It's not that long ago. I mean, in many people's lifetimes. I think just also really important context.

I err on the side of more information than less. So - and it doesn't mean you can't be concise.

Dave Lawrence: Terminology is also difficult. I think, again, going back to what evidence that we can use what we can parse out, I think it's more important to point out the emotional connections that these folks had with one another and no matter what their physical intimacy might have been. Obviously von Scheuben remained deeply devoted to Benjamin Walker and North for much of for the rest of his life.