Part of a series of articles titled On Their Shoulders: The Radical Stories of Women's Fight for the Vote.

Article

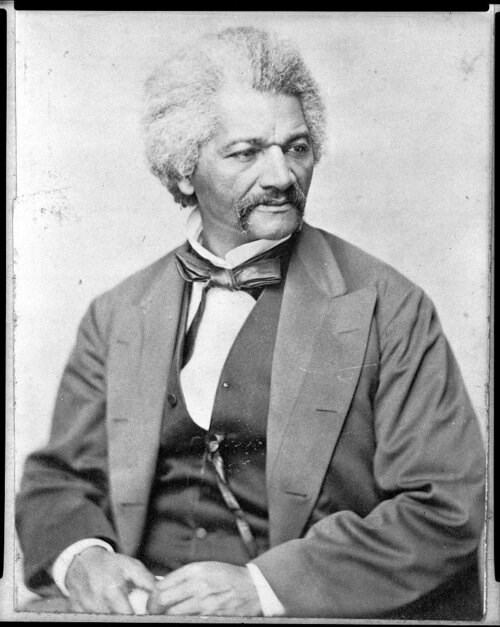

Fraught Friendship: Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass

By Ann D. Gordon

Conflicts between Anthony and Douglass stand out in historical memory. There was drama in a meeting in 1869, for example, when Anthony told Douglass that wronged as he was as a black man, he would never “exchange his sex & color” to be a white woman. Douglass rose to interrupt her: “Will you allow me a question?” “Yes;” she replied, “anything for a fight today.”[2] Friendships, historical or otherwise, are rarely static over decades. At the time of his death, Douglass and Anthony had known each other for about forty-five years, having met in Rochester, N.Y., when Anthony settled there in the summer of 1849. She knew of Douglass before they met; the former slave was already famous as an orator, newspaper publisher, and participant in the woman’s rights conventions of Seneca Falls and Rochester in 1848. He was also a friend of her father.

Throughout the tumultuous second half of the nineteenth century, these friends, nearly the same age, butted heads more than once. Because they were people of strong convictions, their pursuits sometimes overlapped and sometimes collided. Most famously, they clashed after the Civil War, while the Fifteenth Amendment was debated in Congress and awaited ratification in the states. Immediately after the war, they played on the same team as officers of the American Equal Rights Association, founded, as its name indicates, to press for equal rights for all citizens, black and white, men and women. To audiences in 1866 and 1867, Douglass proclaimed: “I am here to advocate a genuine democratic republic; keep no man from the ballot box or the jury box or the cartridge box, because of his color–exclude no woman from the ballot box because of her sex.”[3] It was an ideal on which Douglass and Anthony could agree.

Douglass changed his tune late in 1867, persuaded that extending suffrage only to black men had a realistic chance of passage in Congress; universal suffrage did not. Through 1869, he acted as the Republican Party’s point man to rally woman suffragists to fight for manhood suffrage. At a meeting of the American Equal Rights Association in May 1868, he tried to make women’s dependence a virtue. “You women,” he began, meaning white women, “have representatives. Your brothers, and your husbands, and your fathers vote for you, but the black wife has no husband who can vote for her.”[4] Speaking to the New England Woman Suffrage Association later that year, he argued that real danger–indeed, death–threatened freemen if they were not recognized in the fullness of their citizenship and given the right protective of other rights. And in the course of that argument, he stopped talking about black women altogether: “If the elective franchise is not extended to the negro, he dies–he is exterminated.”[5]

There were smaller disagreements to come, but as soon as the Fifteenth Amendment was ratified in 1870, Douglass returned to the fight for woman suffrage. In January 1871, he was back on the platform at a suffrage meeting in Washington with Susan B. Anthony. He told the assembled suffragists, as reported in the press, “Having himself at last reached the position of citizen, he could not but do his best to extend the same right to every individual, whether male or female.”[7] From that point forward, he was a regular presence at meetings of the National Woman Suffrage Association. Off the platform, a quiet friendship resumed too. He dined at Anthony’s house in Rochester when in town, and she paid calls on him when she was in Washington.[8]

No one knows why Frederick Douglass decided to visit the National Council of Women on that fateful day in 1895. There is a strong possibility that he appeared not to greet old friends but to visit the record number of African-American women participating in the meeting. In a decade when the racial integration of white women’s national organizations produced conflicts, the National Council at this meeting scheduled African-American women to make presentations and listed sixteen delegates from the National Colored Women’s League in attendance.[9] This integrated gathering of women was primed to honor Douglass’s memory. Susan B. Anthony was an author of a resolution adopted unanimously by Council delegates, circulated to the press, and read aloud at Douglass’s funeral, proclaiming that “[t]he woman movement found in him a friend and champion,” while Douglass “made their cause his own.”[10] Anthony reached out to Elizabeth Cady Stanton in New York and implored her to write a tribute to Douglass. In the days after Douglass’s death, newspapers published preliminary plans for the funeral, including lists of speakers–all men.[11] That plan changed. When May Wright Sewall, president of the National Council, rose to speak at the funeral, she explained that she did so at the invitation of the family.[12] When Susan B. Anthony had paid a condolence call on Helen Douglass, Sewall had accompanied her.[13] After that, a place for white women had been found at the end of a lengthy funeral program. Anthony said very little in her own words but read the tribute that she had insisted Elizabeth Cady Stanton send for the occasion. And then the Rev. Anna Howard Shaw delivered a closing prayer. Ties that bound Frederick Douglass to the history of women’s rights and woman suffrage were on display.

As things turned out, Susan B. Anthony’s embrace of the memory of Douglass in death exposed tensions in American society that marred the reform movement she led. Carrie Chapman Catt, then rising in the ranks of the national suffrage association, complained that organizing for woman suffrage in southern states had been badly damaged by “the relation of our leaders to the colored question at the Douglass funeral. . . They were a little suspicious of us all along, but now they know we are abolitionists in disguise, with no other thought than to set the negro in dominance over them.”[14] The white journalist Kate Field attended Douglass’s funeral and described it in detail. “I could not but ask why no colored woman sat on the platform and why no colored women spoke for her sex? It was a mistake, but most obsequies are full of mistakes.”[15] Both reactions highlighted the fractured world that Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass navigated.

Author Biography

Ann D. Gordon, is Research Professor Emerita of history at Rutgers University and editor of the six-volume Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. She has written numerous articles on women’s history, biography, and historical editing and also compiled a collection of essays by scholars of black history, African American Women and the Vote, 1837–1965. In advance of the Nineteenth Amendment centennial, she served as a historical advisor to the National Archives for its exhibit “Rightfully Hers: American Women and the Vote.”

Footnotes

[1] "Fred Douglass is Dead,” Washington Post, February 21, 1895.

[2] Remarks to American Equal Right Association, May 12, 1869, in Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, ed. Ann D. Gordon (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press 1997-2013), vol 2: 238-241.

[3] “Sources of Danger to the Republic,” February 7, 1867, in The Frederick Douglass Papers: Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews, eds. John W. Blassingame and John R. McKivigan (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1991), vol. 4:158.

[4] American Equal Rights Association, May 14, 1868, Douglass Papers, Series One, 4:175.

[5] New England Woman Suffrage Association, November 19, 1868, Douglass Papers, Series One, 4:183.

[6] Remarks to Union League (Colored), No. 23, June 22, 1868, Stanton and Anthony Papers, 2:145.

[7] Washington National Republican, January 13, 1871.

[8] Diary of Susan B. Anthony, August 24, 1888, Susan B. Anthony Papers, Library of Congress.

[9] Program, Second Triennial Session, National Council of Women, February 17 to March 2, 1895, in Susan B. Anthony Scrapbook, vol. 23, Susan B. Anthony Papers, Library of Congress.

[10] Helen Pitts Douglass, Frederick Douglass: In Memoriam (Philadelphia: John C. Yorston & Co., 1897), 95-97.

[11] For example, see Washington Post, February 24, 1895.

[12] H. Douglass, In Memoriam, 45-47.

[13] Diary of Susan B. Anthony, February 24, 1895, Susan B. Anthony Papers, Library of Congress.

[14] Carrie Chapman Catt to Lillie Devereux Blake, March 7, 1895, Lillie Devereux Blake Papers, Missouri History Museum, St. Louis, MO.

[15] Kate Field’s Washington, 11, no. 9, March 2, 1895.

Bibliography

Blight, David W. Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

Brooks, Robin. “Looking to Foremothers for Strength: A Brief Biography of the Colored Woman’s League,” Women’s Studies 47:6 (2018) 609-616.

Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, Washington, D.C.

Frederick Douglass Papers Project, Digital Edition, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.

History and Minutes of the National Council of Women of the United States, ed. Louise Barnum Robbins (Boston: E. B. Stillings & Co., 1898), 161-250.

National Susan B. Anthony Museum & House, Rochester, N.Y. – Resources.

Sherr, Lynn. Failure is Impossible: Susan B. Anthony in Her Own Words. New York: Times Books, 1995.

Smart, Mat. The Agitators: The Story of Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass. New York: Samuel French, 2019. [Also produced as a podcast]

Ann D. Gordon, is Research Professor Emerita of history at Rutgers University and editor of the six-volume Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. She has written numerous articles on women’s history, biography, and historical editing and also compiled a collection of essays by scholars of black history, African American Women and the Vote, 1837–1965. In advance of the Nineteenth Amendment centennial, she served as a historical advisor to the National Archives for its exhibit “Rightfully Hers: American Women and the Vote.”

Footnotes

[1] "Fred Douglass is Dead,” Washington Post, February 21, 1895.

[2] Remarks to American Equal Right Association, May 12, 1869, in Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, ed. Ann D. Gordon (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press 1997-2013), vol 2: 238-241.

[3] “Sources of Danger to the Republic,” February 7, 1867, in The Frederick Douglass Papers: Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews, eds. John W. Blassingame and John R. McKivigan (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1991), vol. 4:158.

[4] American Equal Rights Association, May 14, 1868, Douglass Papers, Series One, 4:175.

[5] New England Woman Suffrage Association, November 19, 1868, Douglass Papers, Series One, 4:183.

[6] Remarks to Union League (Colored), No. 23, June 22, 1868, Stanton and Anthony Papers, 2:145.

[7] Washington National Republican, January 13, 1871.

[8] Diary of Susan B. Anthony, August 24, 1888, Susan B. Anthony Papers, Library of Congress.

[9] Program, Second Triennial Session, National Council of Women, February 17 to March 2, 1895, in Susan B. Anthony Scrapbook, vol. 23, Susan B. Anthony Papers, Library of Congress.

[10] Helen Pitts Douglass, Frederick Douglass: In Memoriam (Philadelphia: John C. Yorston & Co., 1897), 95-97.

[11] For example, see Washington Post, February 24, 1895.

[12] H. Douglass, In Memoriam, 45-47.

[13] Diary of Susan B. Anthony, February 24, 1895, Susan B. Anthony Papers, Library of Congress.

[14] Carrie Chapman Catt to Lillie Devereux Blake, March 7, 1895, Lillie Devereux Blake Papers, Missouri History Museum, St. Louis, MO.

[15] Kate Field’s Washington, 11, no. 9, March 2, 1895.

Bibliography

Blight, David W. Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

Brooks, Robin. “Looking to Foremothers for Strength: A Brief Biography of the Colored Woman’s League,” Women’s Studies 47:6 (2018) 609-616.

Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, Washington, D.C.

Frederick Douglass Papers Project, Digital Edition, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.

History and Minutes of the National Council of Women of the United States, ed. Louise Barnum Robbins (Boston: E. B. Stillings & Co., 1898), 161-250.

National Susan B. Anthony Museum & House, Rochester, N.Y. – Resources.

Sherr, Lynn. Failure is Impossible: Susan B. Anthony in Her Own Words. New York: Times Books, 1995.

Smart, Mat. The Agitators: The Story of Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass. New York: Samuel French, 2019. [Also produced as a podcast]

Last updated: December 14, 2020