Last updated: March 19, 2025

Article

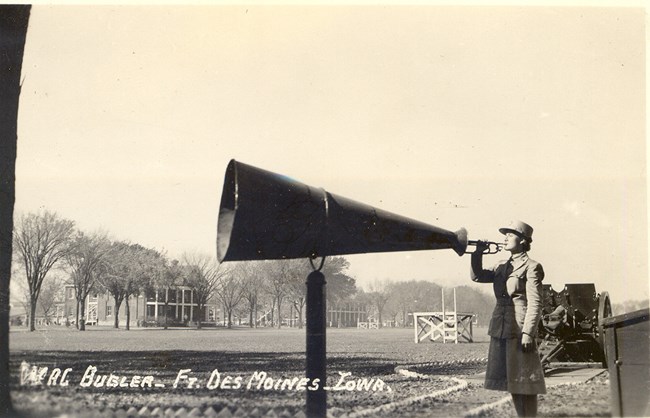

Fort Des Moines: A Series of Firsts in Wartime Service

Courtesy of Hank Zaletel. All Rights Reserved.

Fort Des Moines is a military installation in Des Moines, Iowa. During World War I, the fort served as the first and only training site for African American officers. During World War II, Fort Des Moines was the first training site for the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) and the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), and the only training site for WAC and WAAC officers.

Establishing the Fort

Fort Des Moines was established in 1901 in Des Moines, Iowa. Centrally located and near a number of rail lines, Des Moines was an ideal place for holding troops. The initial construction for the fort finished in 1903. In December 1903, two companies from the all-Black 25th Infantry arrived. They were the first soldiers to inhabit the fort, but their stay was only temporary. The Eleventh Cavalry arrived shortly after and was the first permanent regiment assigned to the post.

Construction continued at the fort until 1907. When completed, the fort consisted of brick quarters, stables, and storehouses of the newest military design. After October 1904, the post also had electric lights. These factors made Fort Des Moines known as “The Ritz Carlton of the Army.” In September 1909, an army tournament involving infantry, cavalry, and artillery occurred at Fort Des Moines. The tournament included contests like wall scaling, bridge building, horse racing, and tug-of-war. President William H. Taft attended and presented prizes to contest winners.

Public domain. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

World War I African American Officer Training Center

Once the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, the US Army selected Fort Des Moines as a training site for African American officers. The selection was at the urging of organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and civil rights activists like W. E. B. Dubois. Several universities petitioned for a selection as well, most notably Howard University in Washington, DC.

On June 17, 1917, 1,250 African American college graduates were sworn in for training at Fort Des Moines. Their training course lasted three months. Once they graduated, they would serve as infantry officers for the US Army’s 16 all-Black infantry regiments. The officers' training should have ended in September, but the War Department pushed back the date, as they had delayed the call for Black soldiers. Finally, on October 15, 1917, 639 officers graduated and received their commissions from the Adjutant General. Officers left Des Moines to serve at military installations around the country, and eventually fought on the front lines in France. At least seven officers who trained at Fort Des Moines received the Distinguished Service Cross. Several others received the Croix du Guerre from the French government for their heroic actions.

Photo by Paul Thompson. Public domain. Courtesy of the National Archives.

In addition to officers’ training, Fort Des Moines also hosted a training camp for African American medical personnel from July to November 1917. Graduates of this five month course included 104 medical officers, 12 dental officers, and 948 enlisted men.

The camp reflected the prejudices of both the military and society at the time. White officers instructed the trainees, and no graduate was commissioned higher than a captain. Black officers were only allowed to command Black infantry regiments. The officers were also only given infantry training, whereas white officers could have infantry, artillery, or cavalry training.

The cadets dealt with hostile citizens in Des Moines as well. To combat this, camp commander Lieutenant Colonel Charles C. Ballou organized a program called a “White Sparrow Patriotic Ceremony." On July 22, 1917, the cadets sang spirituals at nearby Drake University stadium to an audience of 15,000 spectators. Witnesses later stated that the event had given them an “increased regard” for the soldiers.[1]

Public domain. Courtesy of the National Archives.

In August 1918, Fort Des Moines converted into a hospital to provide treatment to bedridden soldiers. It became a general hospital on September 21, 1918. The hospital received a wave of patients after the Armistice on November 11, 1918, and stretched its 1,500 bed capacity to welcome 1,829 soldiers. The hospital’s primary specialty was providing orthopedic treatment to casualties from Europe, including many soldiers who received amputations in Europe. Facing a shortage of supplies, the fort’s orthopedics workshop invented innovative prosthetic designs. The “Fort Des Moines Leg” was quicker to produce, more durable, cheaper, and easier to fit than the government provisional leg.

The Red Cross also held classes for patients at the fort. Class topics included animal husbandry, auto repair, reading, typing, arithmetic, stenography. These classes intended to provide amusement for patients, but also to hone occupational skills and prepare for life after the war.

In October 1919, the hospital was placed under a quarantine order due to the outbreak of the Influenza Pandemic of 1918. Around 300 cases of the flu were reported at Fort Des Moines. The number of patients declined in the fall of 1919, and the Surgeon General decided to close the hospital. During the interwar years, it returned to its previous occupation of a cavalry post.

Courtesy of Hank Zaletel. All Rights Reserved.

The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps and the Women’s Army Corps

In early 1941, Fort Des Moines underwent a transformation from a cavalry post to an induction center for newly-drafted troops. It served this purpose for only a few months. In 1942, the War Department selected Fort Des Moines to be the new site for a Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) officer training center.

The idea of a women’s service branch was not originally embraced by government officials. Without the support of the War Department, Representative Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts introduced a bill in May 1941. She felt that if women were officially inducted into the military, they would receive more protection and better care while serving than the volunteers in World War I had received. The bill was largely ignored until the United States entered the war on December 8, 1941. The Army realized total warfare would require a large workforce, and that women could contribute to the Armed Forces’ labor needs.

Courtesy of Hank Zaletel. All Rights Reserved.

On May 15, the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was officially created. WAACs would serve with the Army, but not in the Army. They would receive food, uniforms, accommodation, pay, and medical care, but they did not receive overseas pay, government life insurance, veterans’ medical coverage, and death benefits granted to male Army soldiers. The Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, appointed Texas native Oveta Culp Hobby as its director. Hobby had previously served in the Texas Parliament, and she was the wife of former Texas Governor William P. Hobby.

The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps was a huge success in the United States. The Army realized the benefit of sending WAACs overseas, but realized the women would need the pay, protection, and benefits afforded to soldiers inducted into the Army. In July 1943, Congress created the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), which inducted women directly into the Army. Previously enlisted WAACs could either join the WAC or return to civilian life. Seventy-five percent of WAACs chose to become WACs.

Courtesy of Hank Zaletel. All Rights Reserved.

WAACs and WACs at Fort Des Moines during WWII

More than 35,000 women applied to be in the first officer training class at Fort Des Moines. The Army accepted 440. This included 40 African American women. Once inducted, the candidates underwent an 8 week training course. Most of the first graduates stayed at Fort Des Moines to train the next round of recruits, but others went to other training sites to train new recruits. Other officers accompanied WAAC auxiliaries to military installations around the country. Simultaneously, 330 auxiliaries (enlisted women) began a shorter course at the fort.

Enlisted enrollees trained for positions like clerks, drivers, cooks, machinists, and messengers. Although the War department established three other WAAC and WAC sites in the United States, Fort Des Moines was the only site that trained officers.[2] Living in renovated stables on a cavalry fort, WAACs and WACs were dubbed “Hobby Horses.”

Between 1942 and 1945, 72,141 women passed through Fort Des Moines. After their training, these women served in all areas and theaters of war. Following the end of the war in 1945, the fort became a WAC separation center. Around 10,000 women transitioned back into civilian clothes here.

Courtesy of Hank Zaletel. All Rights Reserved.

After the war, the Army abandoned Fort Des Moines, and it turned into housing. The fort property was fractured and the now-divided land has many different purposes. These include a Fort Des Moines Museum, The Des Moines Zoo, and housing.

Fort Des Moines was surveyed by the Historic American Building Survey (HABS) in 1987. HABS reports provide written histories, measured drawings, and photos to document sites in case they are modified or demolished. The Fort Des Moines Provisional Army Officer Training School was added to the National Register of Historic Places and became a National Historic Landmark on May 30, 1974.

The content for this article was researched and written by Hannah Haack, an intern with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education and the Park History program.

Chase, Hal S. “Struggle for Equality: Fort Des Moines Training Camp for Colored Officers, 1917.” Phylon (1960-) 39, no. 4 (1978): 297–310. https://doi.org/10.2307/274896.

Greene, Jerome A. “Fort Des Moines Historic Complex.” Written Historical and Descriptive Data, Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1987. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS No. IA-121). Accessed August 11, 2022. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/ia/ia0100/ia0160/data/ia0160data.pdf.

Greenlee, Marcia M., Nancy Witherell, and Suzanne Evans. “Fort Des Moines Provisional Army Officer Training School.” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1973). https://catalog.archives.gov/id/75338177.

Stevens, Peter F. “Every Man Will Be Measured on His Merits.” The Iowan (Fall 1992).

Treadwell, Mattie E. The Women's Army Corps. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1991.

Tags

- world war i

- wwi

- world war ii

- wwii

- wwii home front

- world war ii home front

- military history

- us army

- african american history

- african american history and culture

- black history

- african american heritage

- disability history

- healing

- women's history

- waac

- wac

- women's army auxiliary corps

- women's army corps

- iowa

- habs

- historic american buildings survey

- national historic landmark

- african american

- training

- american military