Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Black Cowpokes in the American West .

Article

Engaging with Cowpoke History

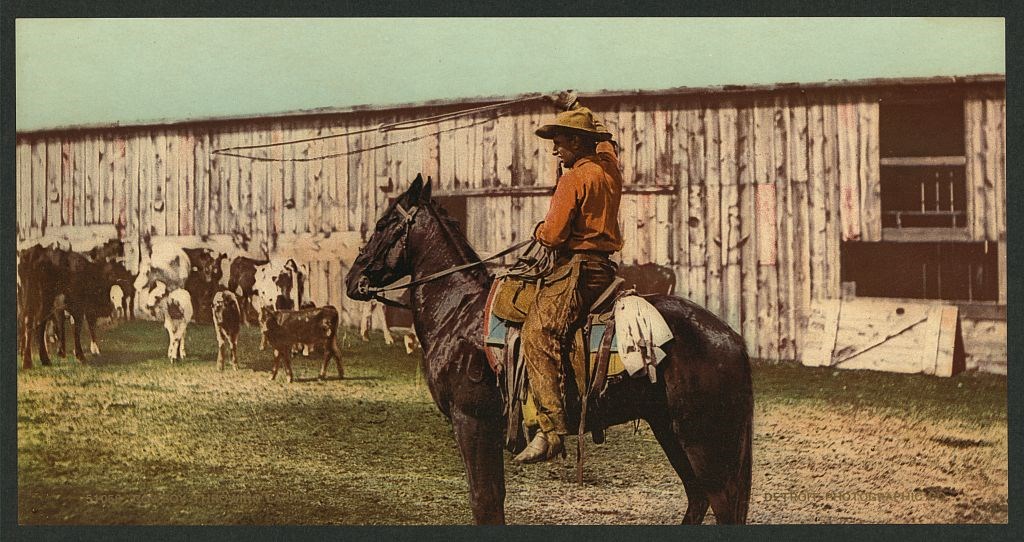

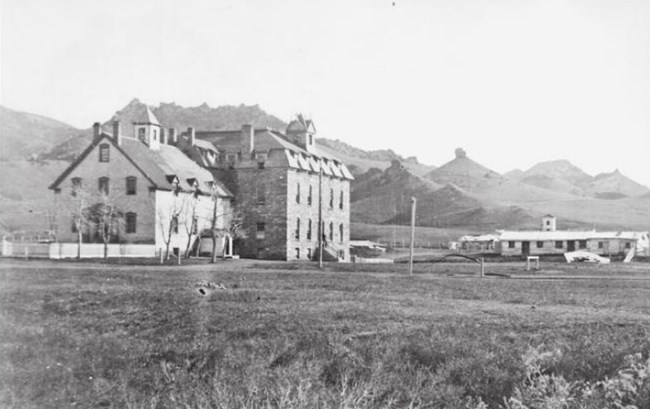

Courtesy of Library Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2008678068/.

The content for this article was researched and written by Dr. Katherine Crawford-Lackey.

Curious about Cowboys and Cowgirls?

-

What do you think of when you hear the term “cowboy”?

-

One out of every four cowboys was African American. Why do you think this job was appealing to African Americans in the aftermath of the Civil War?

Objectives:

-

Describe the Black cowboys and cowgirls who worked on the western frontier and the tasks they took on.

-

Determine the central ideas or information from primary sources such as posters and songs.

-

Identify aspects of these primary sources that reveal an author’s point of view or purpose.

Background:

If your initial definition of a cowboy (also known as a “cowpoke”) is a gun-slinging, rugged fellow on horseback, then you’re not alone! Over the past century, cowboys have taken on a mythic status. When Americans developed a taste for beef in the late 1800s, cattle ranchers hired cowboys to guide the animals to railroad depots. The cattle were then shipped across the country. The concept of the cowboy eventually came to symbolize much more than cattle herding. A romantic hero portrayed in books, movies, and songs, they’ve become a symbol of the American West.

There is a bit more to the history of the cowboy than skilled marksmanship and cattle wrangling. In fact, despite how they are shown in movies and other popular media, many cowboys were Black.

Cattle herding in the western states became a way to escape the racial discrimination of the South. Many Black cowboys and cowgirls, such as Nat Love, Bose Ikard and Mary Fields, were once enslaved. Some, like Love, emancipated themselves and found work herding cattle. Others gained freedom after the Civil War in 1865.

After emancipation, many African American men and women sought a new life out west. They established a number of all-Black towns, including Nicodemus in Kansas. Some of these men and women worked as cowpokes. While not totally free from racial discrimination, many did well in this profession and were respected for their skills. Working as a cowboy or cowgirl was a way to earn decent wages without a great deal of oversight from white employers, and fellow white cowboys were usually friendly with their Black coworkers.

We have more records about the lives of Black cowboys than we do on Black cowgirls. We do know that a lot of women were living in the West when cowboying became popular. Census records indicate that over 800,000 women resided west of the Mississippi River by 1900. Ranchers rarely employed women (white or Black) as cowpokes, but a small number of women worked on cattle ranches. Historical documents such as property deeds also prove that a small number of Black and Latina women owned and managed their own ranches. These women oversaw daily operations and were skilled horse riders and cattle wranglers. A number of women also performed in the wild west shows that were popularized by Buffalo Bill in the 1870s.

The following activities offer opportunities to learn about Black cowpoke and their experiences in the Wild West.

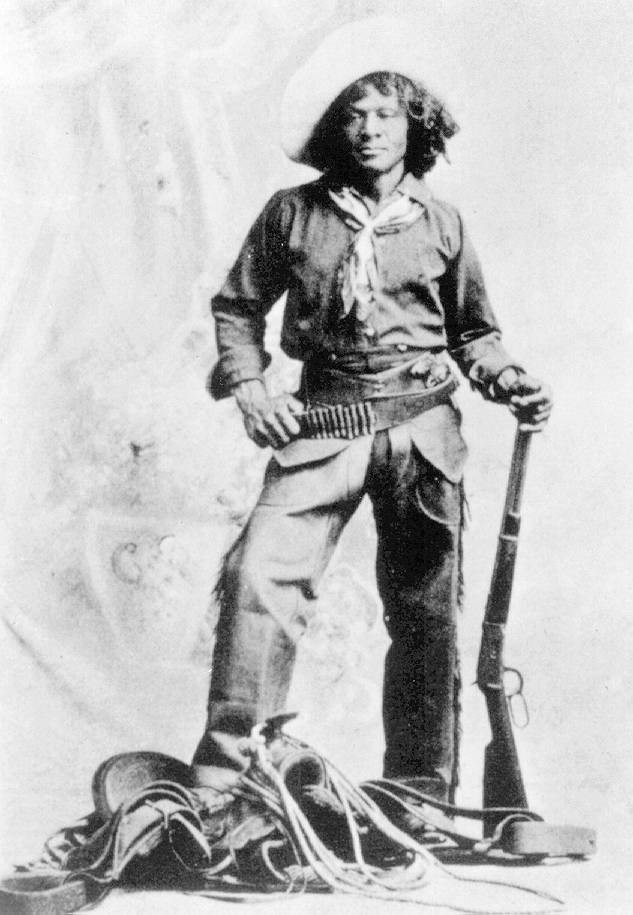

Photo courtesy National Park Service, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5194967

Activity 1:

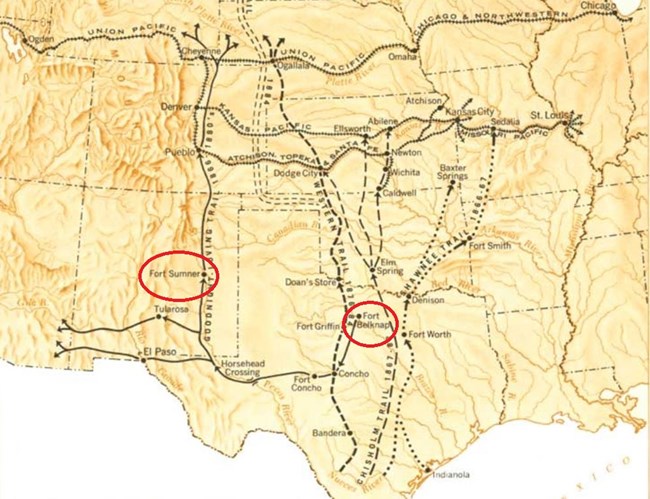

In the 1860s, white cowboys Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving partnered to herd Texas Longhorns across the state of Texas. Hiring a group of 18 cowboys, including Black cowpoke Bose Ikard, Goodnight and Loving forged a trail from Fort Belknap, Texas to Fort Sumner, New Mexico, two 19th century forts listed in the National Register of Historic Places. This route was eventually named the Goodnight-Loving Trail after the two cowboys.

While the trail is named in honor of Goodnight and Loving, Ikard performed the important work of tracking and wrangling cattle across the several hundred mile trail. Ikard also protected Goodnight's valuables, and he often carried thousands of dollars in cash that he kept safe from bandits and raiding parties.

While cowboying could be profitable, it was also dangerous. Loving was injured when a raiding party attempted to steal their cattle. He later died of infection. Goodnight and Ikard escaped injury, but they continued to endure the hardships of the job. One section of the trail was particularly unpleasant; the men had to cross approximately 100 miles of desert relying on whatever food and water they had with them. It’s no wonder Ikard retired after a few years, purchasing his own ranch and raising a family in Parker County, Texas.

Listen to this song about the Goodnight-Loving Trail and make your own judgment about what life was like on the trail. As you listen, consider the perspective of the singer. Who are they and what message are they trying to get across? Feel free to follow along with the lyrics below. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U80vZAo2R4Q&pbjreload=101

Too old to wrangle or ride on the swing,

You beat the triangle and you curse everything.

If dirt was a kingdom, they you'd be the king.

On the Goodnight Trail, on the Loving Trail,

Our Old Woman's lonesome tonight.

Your French harp blows like the low bawling calf.

It's a wonder the wind don't tear off your skin.

Get in there and blow out the light.

With your snake oil and herbs and your liniments, too,

You can do anything that a doctor can do,

Except find a cure for your own bad plain stew

The campfire's gone out and the coffee's all gone,

The boys are all up and they're raising the dawn.

You're still sitting there, lost in a song.

The campfire's gone out and the coffee's all gone,

The boys are all up and they're raising the dawn.

You're still sitting there, lost in a song.

I know that some day I'll be just the same,

Wearing an apron instead of a name.

There's nothing can change it, there's no one to blame

For the desert's a book writ in lizards and sage,

Easy to look like an old torn out page,

Faded and cracked with the colors of age.

The campfire's gone out and the coffee's all gone,

The boys are all up and they're raising the dawn.

You're still sitting there, lost in a song.

Based on the song, what do you think it was like navigating the Goodnight-Loving Trail?

Does this song align with your initial ideas about cowboys? Why or why not?

Do you think you would choose this job? Why or why not?

Activity 2:

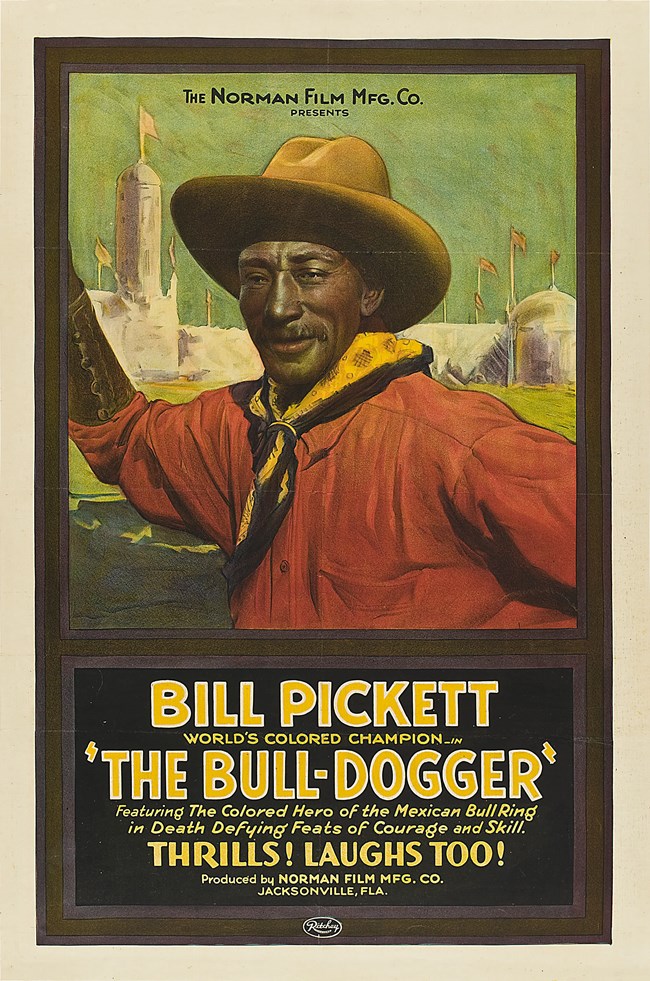

Bill Pickett was one of the most famous African American cowpokes. He learned cowboying as a ranch hand in Texas and eventually used his skills to become a famous performer. He starred in world famous Wild West shows and even performed for British royalty.

Pickett was also the subject of a 1922 silent western film, The Bull-Dogger. Filmmaker Richard Norman was impressed not only with Pickett’s skills, but also with his ability to please the crowds. Inspired by the Black cowboy’s journey to fame, Norman directed a film about the rodeo legend. Named after the rodeo trick Pickett became known for, the film depicts Pickett on horseback, lassoing and wrestling a cow.

The movie poster is depicted in the image to the left. Who do you think is the intended audience?

How is Bill Pickett depicted in the image?

What movies or TV shows do you know about cowboys? How are these cowboys often depicted?

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25212558

Activity 3:

Mary Fields was an adventurous and resilient Black pioneer. Born enslaved in Tennessee in the early 1830s, she gained her freedom after the Civil War and traveled around the southern US. She eventually made her way to a convent (a Catholic religious institution for women) in Toledo, Ohio where she worked for a number of years. In her fifties, Fields left the Ohio convent and moved over 1,600 miles away to St. Peter’s Mission in Montana.

We don’t know a lot about her day-to-day life as Fields did not write a memoir. However, we do know that she moved around a lot! Throughout her life, Fields traveled by boat, train, and stagecoach to different parts of the country. Moving from place to place, she uprooted her life to start anew. She likely could only bring a select few items each time she moved. What items do you think she carried with her? What items would you keep with you? Why?

For this activity, “pack” your own bag of possessions. Remember, you bag is only so big! You can only fit 4 to 6 items. What do you need? What items could you do without? How do you make these decisions? What item is particularly important to you? Why?

Closing Thoughts:

By the 1890s, ranchers began favoring barb-wire fencing to control their cows instead of hiring cowboys. As more and more meat-processing plants were built across the US, cowpokes were no longer needed to drive cattle. As the days of guiding steer across vast tracts of land were ending, a new past time developed: the rodeo. Wild West shows became popular in the late 1880s, and often featured “cowboy tournaments.” Cowboying became a way to entertain audiences. Black and white cowboys and cowgirls showed off their horseback riding and bull wrangling skills. By the early 1900s, cowboying had taken on new meaning. More than a job, it had become a symbol of American individualism and grit.

Making Connections:

Cowboying was one of the more accepting professions in the late 19th century, but it was still not a fully inclusive discipline. Rodeo star Bill Pickett, for example, often faced discrimination despite his skills and fame. Some ranchers and performance venues banned Pickett from performing because of the color of his skin.

Where do we see discrimination in the workplace today?

The passage of civil rights laws in the 1900s has helped protect the rights of people of color, women, and people of different religions and nationalities. Who isn’t included in this list? How might these people be vulnerable to discriminatory employment practices?

Bibliography:

Durham, Philip and Everett L. Jones. The Negro Cowboys. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965.

Garceau-Hagen, Dee. Portraits of Women in the American West. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Hagan, William T. Charles Goodnight: Father of the Texas Panhandle. University of Oklahoma Press: 2012.

Hanes, Billy C. Bill Pickett, Bull-Dogger: The Biography of a Black Cowboy. Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1989.

Hardaway, Roger D. “African American Cowboys on the Western Frontier.” Negro History Bulletin 64, no.1 (January-December 2001): pp.27-32.

Liles, Deborah M. and Cecilia Gutierrez Venable, eds. Texas Women and Ranching: On the Range, at the Rodeo, and in their Communities. College Station: Texas A&M, 2019.

McConnell, Miantae Metcalf. “Mary Fields’s Road to Freedom.” In Black Cowboys in the American West: On the Range, on the Stage, and Behind the Badge. Eds. Bruce A. Glasrud and Michael N. Searles. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma, 2016.

Nodjimbadem, Katie. “The Lesser-Known History of African American Cowboys.” Smithsonian Magazine, Feb 13, 2017.

Reindl, JC. “‘Stagecoach Mary’ Broke Barriers of Race and Gender.” The Blade. February 8, 2010, https://www.toledoblade.com/local/2010/02/08/Stagecoach-Mary-broke-barriers-of-race-gender.html.

Tennent, William L. John Jarvie of Brown’s Park. Cultural Resource Series No 7. Salt Lake City: Bureau of Land Management, 1982.

Wagner, Tricia Martineau. African American Women of the Old West. Guilford, CT: Twodot, 2007.

“Deadwood Dick and the Black Cowboys.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. (Winter 1998-1999): pp.30-31.

Last updated: March 25, 2025