Last updated: January 7, 2023

Article

“My Mind was Liberty or Death:” Elizabeth Blakeley’s Escape to Freedom

Boston served as a destination for many people escaping slavery on the Underground Railroad. Freedom seekers arriving in the city found that Boston's tightly knit free Black community provided support and a welcome sanctuary as they began their new lives. This article highlights the journey of a freedom seeker, Elizabeth Blakeley, who escaped to Boston. To explore additional stories, visit Boston: An Underground Railroad Hub.

Born enslaved in North Carolina, Elizabeth Blakeley faced terrible treatment by her enslaver. Determined to escape, Blakeley hid on a vessel headed north to Boston, thwarting authorities attempts to find her. She survived a four-week long journey, arriving in Boston as a free person. A few weeks after her arrival, Blakeley shared her story at an anti-slavery meeting in Faneuil Hall. Due to her courageous escape, Blakeley chose her own life path, living in Toronto and Massachusetts.

Explore the story map below to learn about Elizabeth Blakeley's journey to freedom. Click "Get Started" to enter the map. To read more about each point, click "More" or scroll down to view the map, historical images, and accompanying text. To navigate between the points, please use the "Next Stop" button at the bottom of the slides or the arrows on either side of the main image. To view a larger version of the main image depicted below the map, click on the image.

Footnotes

[1] 18th Annual Report Presented to Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society by it’s Board of Members (Boston, Massachusetts), January 23, 1850.

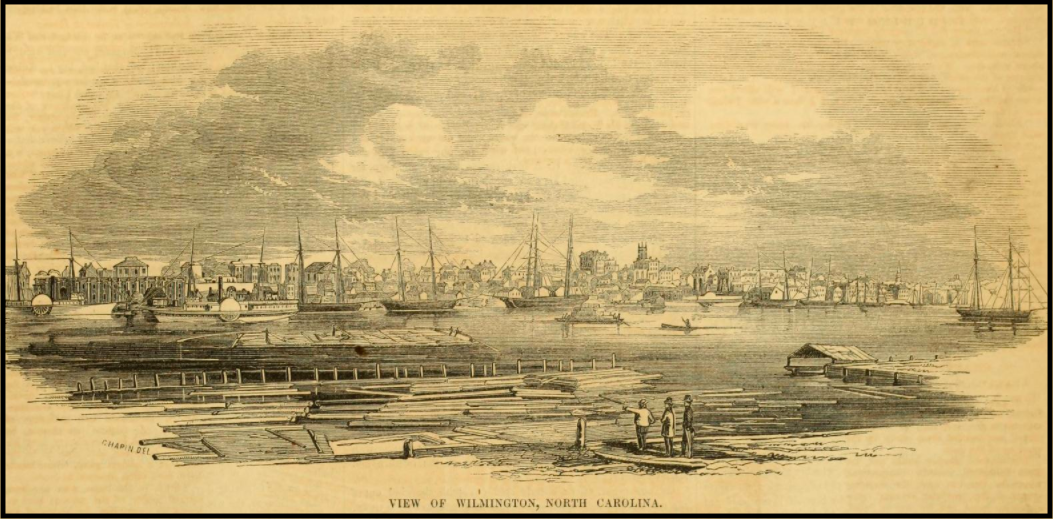

Image: "View of Wilmington, North Carolina," Gleason's Pictorial Drawing Room Companion, ed. Maturin Murray Ballou (Boston : F. Gleason [etc.], 1853), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000055550178&view=1up&seq=45&q1=wilmington.

[2] “Remarkable Escape of Slave,” North Carolina Standard, January 16, 1850.

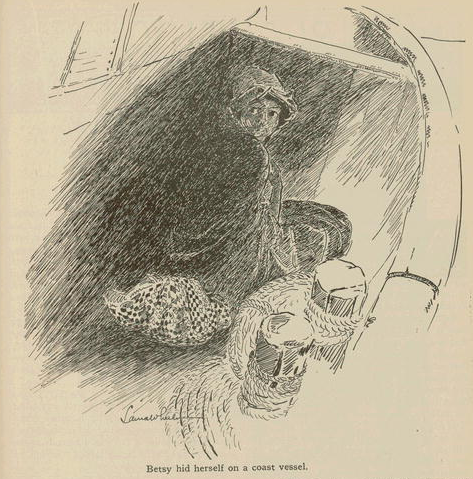

Image: W. E. B. Du Bois, The Brownies' book (New York, N.Y.: DuBois and Dill, to 1921, 1920), Periodical, https://www.loc.gov/item/22001351/.

[3] Austin Bearse, Reminisces of the Fugitive Slave Law Days (Warren Richardson, 1880), 31. Archive.org archive.org/details/reminiscencesfu00beargoog/page/n20/mode/2up/search/trade.

Image: "Faneuil Hall. Built in 1742," Photograph, 1860, Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/s1784x327 (accessed November, 2020).

[4] “Eighteenth Annual Meeting of the Massachusetts A.S. Society,” The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts), February 1, 1850.

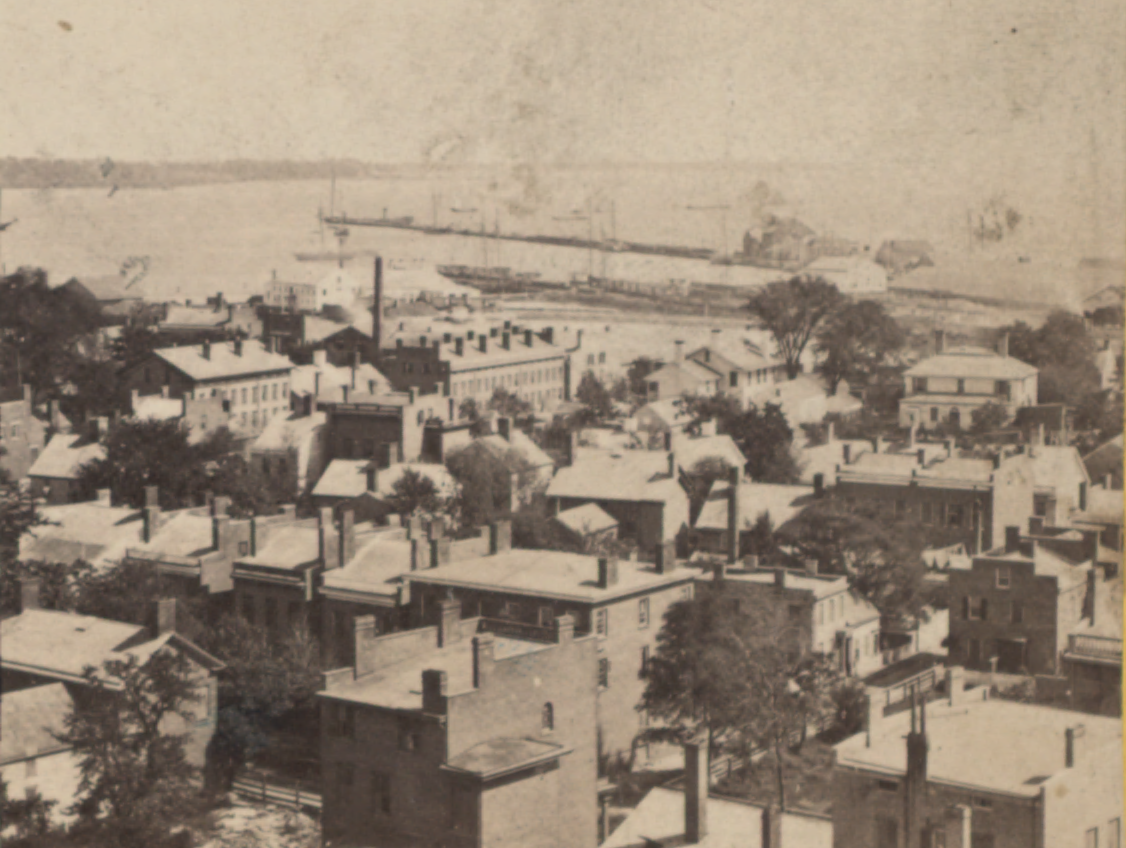

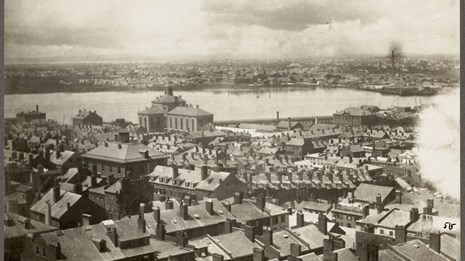

Image: The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library, "Harbor and long Wharf, from Depot Tower, New Haven," New York Public Library Digital Collections, accessed November, 2020. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-6f14-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

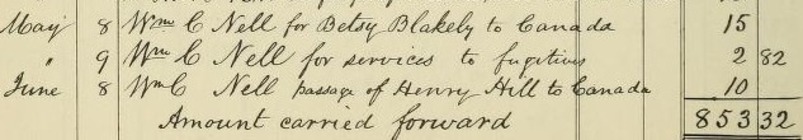

[5] Francis Jackson, Treasurers Accounts: The Boston Vigilance Committee, Bostonian Society, 2011, 52. Archive.org https:/archive.org/details/drirvinghbartlet19bart/page/52/mode/2up

Image: Francis Jackson, Treasurers Accounts: The Boston Vigilance Committee, Bostonian Society, 2011, 52. Archive.org https:/archive.org/details/drirvinghbartlet19bart/page/52/mode/2up

[6] Ethel Lewis, The Celebration of the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Birth of William Lloyd Garrison (Boston: The Garrison Centenary Committee of the Suffrage League of Boston and Vicinity, 1906), Archive.org, 2006. https://archive.org/details/celebrationonehundred00garrrich/page/36/mode/2up?q=betsey

Images: "Interior of Faneuil Hall," Photograph, 1885, Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/p2677g48p (accessed November, 2020); Ethel Lewis, The Celebration of the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Birth of William Lloyd Garrison (Boston: The Garrison Centenary Committee of the Suffrage League of Boston and Vicinity, 1906), Archive.org, 2006. https://archive.org/details/celebrationonehundred00garrrich/page/n7/mode/2up?q=betsey

[7] “Speech of Wendell Phillips, Esq.” Pennsylvania Freeman, February 19, 1852.

Gustav F. Braun, “Woodlawn Cemetery Everett,” NOBLE Digital Heritage, accessed November, 2020, https://digitalheritage.noblenet.org/noble/items/show/612.