Last updated: November 17, 2022

Article

President-Elect Eisenhower's Trip to Korea

National Archives and Records Administration

In late October 1952, the polls were looking very promising for the Republican candidate for president, General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Ike, as he was affectionately known, had a commanding lead over Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson II. Most politicians would not challenge a good thing and would only coast to election day. However, the former Supreme Allied Commander in Europe during World War II was a different type of politician, and coasting was not part of his character.

On October 24, 1952, while campaigning in Detroit, Michigan, Eisenhower announced that he would “forego the diversions of politics and concentrate on the job of ending the Korean War…” He announced to a very attentive audience, “I shall go to Korea.” This was a bold statement, but Eisenhower had made many bold statements in his long and distinguished career.

America’s leading soldier from World War II and the Cold War (as the Supreme Commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization), wanted to see for himself the conditions in a divided Korea. Most Americans liked his announcement and understood that the task of ending the war would be extremely difficult. Unfortunately, President Harry Truman called it a gimmick. If Eisenhower was behind in the polls or was a typical politician, it would be easier to see his statement on Korea as such. But this was not the case with Eisenhower. Having seen war throughout his life, General Eisenhower sought to use his political career to bring about peace. On November 4, 1952, Eisenhower defeated Stevenson in a landslide victory, carrying 442 electoral votes.

National Archives and Records Administration

Despite his public announcement, Eisenhower’s actual journey to Korea was kept secret. It began before he took his oath as the 34th President of the United States. The ten thousand mile trip began on November 29, 1952, at the president-elect’s office and living quarters at Columbia University in Manhattan. The flight stopped in San Francisco, Hawaii, Midway, Iwo Jima, and finally in Seoul. Eisenhower was accompanied by General Omar Bradley, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, and Eisenhower’s friend and classmate from West Point. The party arrived in Seoul on the evening of December 2, 1952.

The first thing that Eisenhower witnessed in Seoul was the utter devastation of the city. The war had begun on June 25, 1950, when communist North Korea invaded the American supported South Korea unprovoked. Seoul had changed hands several times since 1950, and the conditions in the city were horrible.

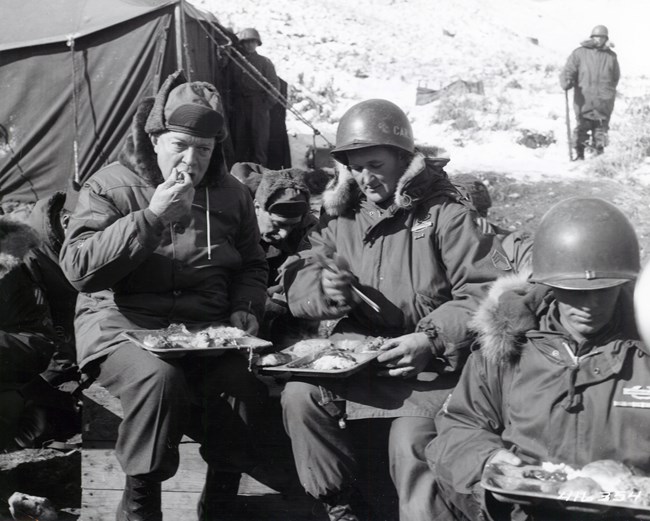

For the next three days, Eisenhower visited senior American officers and common soldiers. Just like his preparation for D-Day on June 6, 1944, Eisenhower thought that he needed to hear about the situation from the junior officers and enlisted soldiers. Ike also saw his son, John Eisenhower, on the front lines of the Korean War. The weather was bitter cold, and Ike wore a U.S. Army type B-9 parka, a fur lined hat, and thermos boots. He ate meals with the troops in the extreme cold.

In general, President Syngman Rhee of South Korea and senior American commanders wanted to expand the war with a massive offensive. Eisenhower listened to their plans and arguments, but he came to realize that a new offensive was madness. To Ike, the situation in Korea was intolerable, and another offensive in the barren and bleak hills and mountains of Korea would just continue the status quo. Ike left Korea with the belief that the bloody stalemate must end.

NPS Photo

The news blackout on the president-elect’s secret trip ended on December 6, 1952. His time in Korea had been informative, but also taxing. Part of the journey home occurred on a U.S. Navy vessel, which gave Eisenhower time to recover and collect his thoughts further. As the president-elect made his way back to the United States, he also enjoyed playing games of bridge to relax at sea.

Shortly after President Eisenhower was inaugurated on January 20, 1953, he tasked his foreign policy team for a negotiated settlement in Korea. While President Truman had started negotiations, the talks had stalled. Eisenhower knew that negotiations with communists would enrage the “old guard,” or the extreme right of the Republican Party. Fortunately, Ike had the political capital and military reputation to withstand intense criticism on this front. Some historians argue that Ike’s willingness to challenge a large percentage of his own party was one of his greatest achievements as President of the United States.

One of the biggest obstacles that Eisenhower had to a compromise with the communists was the leader of South Korea, President Syngman Rhee. He continuously pushed for a new offensive against the north and objected to voluntary repatriation of Chinese and North Korean Prisoners of War (POWs). Ike also had to contend with his own strong-willed Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles who typically agreed with President Rhee.

In the final analysis, Ike thought that an unlimited war in the atomic age made no rational sense. Conversely, a limited war—such as the situation in Korea—was unwinnable and would perpetuate a stalemate. President Eisenhower firmly believed that American soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines should not die in the Korean stalemate.

There is an argument by some historians that Ike used the threat or bluff of using atomic weapons during the negotiations with the communists. Atomic weapons were certainly part of the American arsenal at the time, and Eisenhower had a reputation of a hardened American general. Other historians claim that the Soviet Union pressured Communist China to yield on the repatriation of POWs to ease Cold War tensions. Also, American bombers had done so much damage and devastation to North Korea that the north wanted the armistice.

After being the President for only seven months, Ike delivered an ending to the Korean War. The armistice was signed on July 27, 1953. He held a nationally televised address to the American people explaining the terms of the armistice.

The high cost of American lives on the Korean Peninsula had ceased. During three years of war, 33,686 Americans gave their lives in the Korean War.