Last updated: July 20, 2023

Article

Podcast 104: Earthquake Narratives: Creating a museum exhibit around seismic upgrades

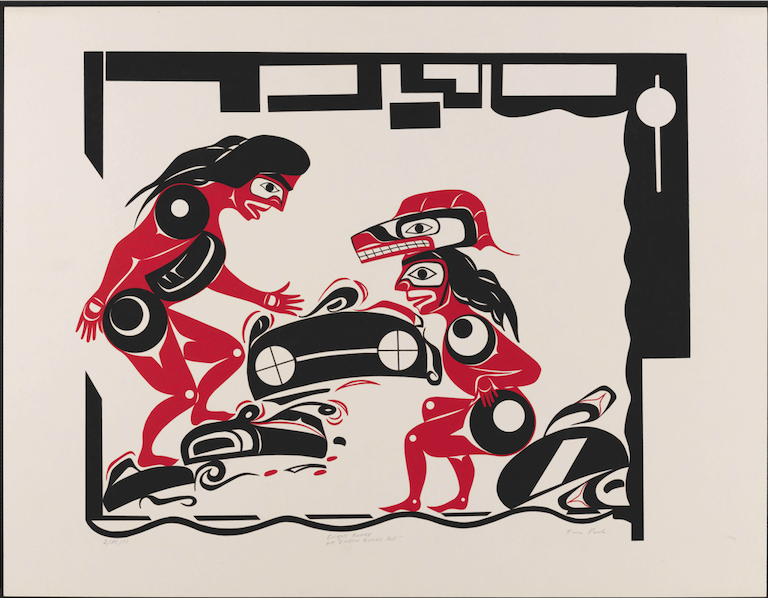

© UBC Museum of Anthropology

Shake Up: Preserving What We Value

Catherine Cooper: What is the Shake Up Exhibit and what was the impetus for creating it?

Jennifer Kramer: The Museum of Anthropology is about to undergo seismic upgrades of a significant portion of our building called the Great Hall to protect against seismic movement of the earth. As a result, the curators were tasked with telling our public what was coming, and what to expect, and what they could learn about the process when they were physically cut off from being in the Great Hall.

The Great Hall is this soaring space of glass filled with totem poles from the First Nations of the Northwest Coast and other monumental sculptures. So, we wanted to prepare people about what they were missing seeing, but also make them understand why it was so important that we preserve what we value.

Seismic Upgrades

Catherine Cooper: When designing this exhibit around these seismic upgrades, how did you and your team decide which narratives to include and how to balance them?

Jennifer Kramer

Jennifer Kramer: I co-curated this exhibit with Curator of Education, Dr. Jill Baird, so it was definitely a team effort.

With her interns in the Department of Education and also with help from other curators in my department, because we have four curators that work with First Nations Northwest Coast peoples here in British Columbia.

It was a learning curve for Jill and I to learn about what causes earthquakes and how they can be mediated. We had to do our own research on protecting historic iconic buildings, of which the Museum of Anthropology is one. It was designed by Arthur Erikson, a Scottish-Canadian architect, who is quite famous for his modernist buildings.

First Nations Musqueam People

But in this case, he was very much also inspired by First Nations longhouse and big house construction and also was inspired by having a building that fit within the land. This is always an important message from the Museum of Anthropology, that we sit on the ancestral, unceded territory of the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓-speaking Musqueam people.

RBCM 15247a

So, while the architecture is modern, it might seem like it’s a different trajectory than seven thousand plus years of inhabited history for the Musqueam people.

There’s actually a tactile relationship with the architecture. So we wanted to preserve the iconic architecture, we wanted to preserve, of course, these incredibly important First Nations totem poles, which tell long standing histories between people, their territories, their ancestors, and how they came to live and steward the land upon which they draw their resources.

But we also realized that it was a bigger story than so-called western science about how do you preserve a material building using—and this is what we’re doing, we’re using something called base isolation, which I have learned a bit about.

Indigenous History of Earthquakes and Tsunami

But what we also realized was beyond the science, the engineering, the architecture, we realized there was so much knowledge within the Indigenous communities who live on the Northwest Coast about how you survive an earthquake and a tsunami.

And we realized that there are multiple ways of knowing and being prepared for what now we think of as these ultimate disasters, but we realized there was knowledge to be learned from talking to Indigenous communities.

Kwiaahwah Jones

So, Jill and I basically looked at the totem poles we had represented in the Great Hall and said, let’s try to do an overview from the north of British Columbia—so we chose a Haida Gwaii Haida artist, Kwiaahwah Jones.

From relatively the south, so we chose Tim Paul, a Hesquiaht Nuu-chah-nulth elder from Vancouver Island.

And we chose someone sort of in the central coast from the Kwakwaka’wakw community, from the Nelson family, Frank Baker and K’odi Nelson.

So we basically asked them, as this kind of north to south representation, of their cultural teachings about earthquakes and tsunamis. And that was where the exhibit exploded. In a wonderful way.

There is actually only one physical belonging, or otherwise known as a treasure maybe, in this exhibit.

It’s a Ninini Kwakwaka’wakw Dzawada’enuxw earthquake mask. Ninini means earthquake.

And it has been in our collection since the 1950s, sold directly from the widow of someone that had owned the rights to dance Ninini as part of his box of treasures in Kingcome Inlet, Gwa’yi, a Dzawada’enuxw Kwakwaka’wakw man.

What was exciting about this exhibit is first, we became involved in figuring out—so just from this one physical object—we did research to figure out whether there were living community members who were attached to this mask that had been in our collection for seventy years. And we were able to find a family that owned that connection and still had that right to dance Ninini.

Jessica Bushey

Dance Ninini at Potlach

And we were invited to a potlatch in Alert Bay, British Columbia in October 2018, to watch a different version of this mask be danced and we recorded it.

We were given permission to record it and show it as a five-minute film. But then due to establishing that relationship with that family, they got closer to the mask in our collection and the following year, a different member of that family, who held that inheritance, asked that the mask that was in MOA’s collection, go up to Alert Bay to be danced in his memorial potlatch in October 2019.

And so, we now have footage of that and what it is, is showing that this cultural heritage, this material heritage is not from the past, that it has ongoing meaningful significance.

It’s a small exhibit but it’s scattered in multiple locations and it covers a tremendous amount of information about what causes earthquakes, tectonic plates, the Ring of Fire, vernacular architecture that worked with protecting buildings from earthquakes like the longhouses on the Northwest Coast.

Timelines of Earthquake and Tsunami

We also share chronologies of earthquakes around the world, beginning with the last major subduction zone Cascadia earthquake that hit the Northwest Coast in 1700.

So, another sort of larger, underlying reason is we know from science and from records around the world that subduction zones, so underwater tectonic plates that suddenly slip causing mammoth sort of scale eight or nine earthquakes, happen about every 250 – 500 years.

Jennifer Kramer

So, we are definitely due for one here in Cascadia. And so, this was getting that message out.

Catherine Cooper: How will these seismic upgrades help protect both the building and the contents of the Great Hall?

Jennifer Kramer: Now, caveat, I am not an architect, but I have spoken to our building people to understand.

Base isolation is a platform which has this ability to move sideways during an earthquake in order to allow the energy of the earthquake to go out sideways instead of forcing the totem poles and the other monumental sculptures in the building to fall down due to vibration.

So it releases the strength of the vibrations.

What we learned was that, we’re going to have to actually take down the building completely in order to put in this base isolation and then rebuild it.

It was somewhat of a shock to us all, but it will be a safer construction if we start from scratch, and it will be built to exactly Arthur Erickson’s vision.

© UBC Museum of Anthropology

But I want to add that the seismic upgrades made us realize not just that we were preserving the iconic building or even preserving tangible material culture, but also that we were working on preserving intangible knowledge, intangible heritage that was part of the mission of the museum.

And so, respecting all of that knowledge about how to be prepared for disasters from First Nations on the Northwest Coast, was also part of what we were preserving, what we all valued.

And so, we were making those different knowledges from the west and from Indigenous people with thousands and thousands of years of history on the land, come together, to work together and that was exciting.

Future of Virtual Exhibits

Catherine Cooper: Because of the pandemic, quite a bit of this material has gone up on MOA’s website. How did you decide what portions to put up on line, and will they remain up beyond the physical exhibit?

Jennifer Kramer: When we all went into lockdown in mid-March, everyone at the museum moved very, very quickly to plan how we could share the work we do at the Museum of Anthropology with the larger public.

One advantage of virtual access is it can be from anywhere in the world if you have the bandwidth. So, in some ways, we’re thinking this is a complete sea-change in how a museum does the work it does.

I doubt we’re going to take down what we’ve already put up. It isn’t about forcing people to come and pay door admission in order to hear these stories about earthquakes, see these dances about earthquakes and longstanding family relationships to specific lands, territories, and resources, songs. I imagine they will stay online.

© UBC Museum of Anthropology

We did a three-hundred and sixty virtual degree tour of the Museum of Anthropology Great Hall that people can go online and experience for themselves. Because I imagine once we get the hoarding wall up, which is supposed to happen in the fall, it probably will be closed to the public for 18 months at least. The Shake Up exhibit will obviously remain.

Exhibits About Natural Disasters

Catherine Cooper: This “Shake Up: Preserving What We Value” exhibit is one of two exhibits that are planned to discuss natural disasters. Can you speak of it to how this exhibit will interact with or converse with the other exhibit?

Jennifer Kramer: I can’t say that we actually planned it this way. It was a lucky happenstance, and especially if you add the pandemic into dealing with global disasters. But the two exhibits do work very nicely together. Our Curator of Asia, Fuyubi Nakamura, has been planning an exhibit called, “A Future from Memory: Art and Life After the Great East Japan Earthquake.” She’s been working with artists that have done contemporary responses to what the 2011 great east Japan earthquake meant and has ongoing meaning. Also, the remnants of what was found from the tsunami, photographs that were lost to people’s families. I know she went, and they had thousands and thousands drying, trying to connect them back to their families. So, it’s been a grand preservation effort of reconnecting individuals to their personal history, but also a country figuring out how to deal with this disaster.

And I would read a statement that she made that I think is really important as to how it connects to Shake Up. She said, “A Future from Memory will show that this disaster is not simply about a region, Tohoku, or a country, Japan, rather this event has global relevance. Fishing boats from Tohoku arrived on the shores of the Pacific Northwest, reminding us that we are connected by the same ocean and are mutually responsible for our environment.”

She put that wonderfully, but it also is what we were thinking about when we did Shake Up. That we’re all in this together, the Ring of Fire circle, the world and so we are all mutually responsible for our human relationship to the earth. It’s about making us all think about the land beneath our feet and how we move forward into the future, knowing that we know there’s going to be another disaster.

Catherine Cooper: Thank you so much for sharing this exhibit with all of us.

Jennifer Kramer: Thank you. It’s been wonderful sharing it with you.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.