Last updated: January 22, 2024

Article

Charlestown Navy Yard: Railroad Tracks

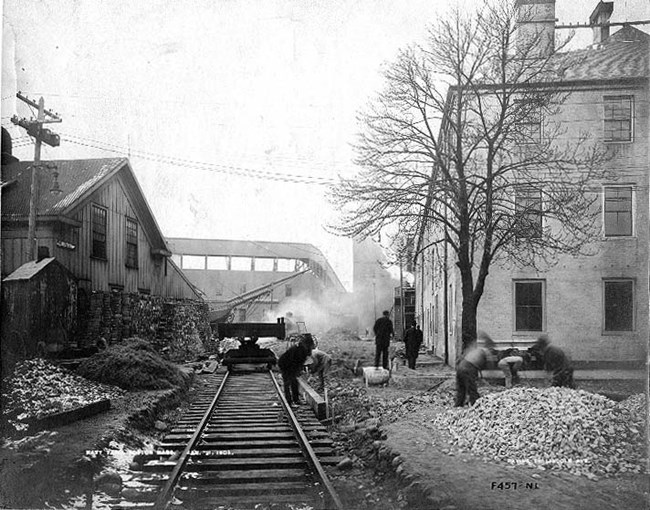

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection.

History Underfoot

If you visit the Charlestown Navy Yard today, you might notice railroad tracks crisscrossing the ground. While many sections are gone—either torn up or paved over—the surviving pieces echo what used to be a busy network of tracks throughout the Navy Yard. On that rail network, small trains once trundled from building to building and out to the dry docks and piers.

Compared to wagons pulled by horses and oxen, the introduction of the railroad in the 1860s allowed the Yard to more easily and effectively transport heavy and bulky materials. Further, a rail connection to the nearby Fitchburg railroad, and later the Boston and Maine railroad, meant the Charlestown Navy Yard was not only interconnected, but it was also more directly accessible to places far beyond its gates.

In the 1950s, however, the US Navy's use of the rails sharply declined. Larger and more powerful trucks, capable of driving anywhere, replaced many roles of the railroad. Nevertheless, 100 years of stalwart service within the Yard still remains visible in the form of surviving railroad tracks.

Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society

Before the Railroad

For decades the Charlestown Navy Yard had no railroad. The early absence can be explained at least partially by the fact that when the Navy Yard opened in 1800, railroads did not really exist.

There were roads made of rails, but these simple wooden or wrought iron "wagonways" and "plateways" found use primarily in mines or quarries. Trains of railcars were either pulled by animals or allowed to roll by gravity. It wasn't until a flurry of invention, including smaller steam engines capable of fitting on a railcar and new metalworking techniques that created stronger, smoother, and cheaper rails, that steam-powered railroads became possible.

By the 1810s, steam engines in Britain pulled heavy coal and iron ore. Trains now proved commercially successful.

Just the Rails

Despite their success, early steam locomotives were still expensive and challenging to maintain. Many early railroads chose not to initially invest in the cutting-edge steam technology. Instead, railroads focused on newly improved rails.

A horse pulling a car along on rails could pull twice what it could on an early 1800s roadway. Many railroads, including the Granite Railway in nearby Quincy, Massachusetts, opted to continue using animal power when it opened in 1826. Considered the first railroad in the United States, the Granite Railway helped haul quarried stone in Quincy to the water, where it was floated to the Bunker Hill Monument site during its construction.

By the 1850s, the Navy began looking at constructing rail lines in some of its navy yards. When it first laid tracks down at the Charlestown Navy Yard in the 1860s, it relied on animal-drawn railcars. These trains proved useful in moving bulk materials like coal around the yard, which was increasingly in demand to fuel metal forges and steam engines in workshops.

A horse and oxen-drawn railroad made sense for the short distances required for a navy yard system, and the Navy Yard could make use of simpler rails than what was needed for steam locomotives. However, the Fitchburg Railroad, which operated in Charlestown just outside the Navy Yard gates, was unable to run its trains on the rails within the Yard. This led the Navy to request funds to update the railroad lines to standard gauge track.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection.

Boston National Historical Park, BOSTS 9252-457

Switching to Steam

The switch to steam locomotives meant the entire rail system had to be overhauled. By 1904 the Navy Yard finally had a modern railroad upon which it could operate. Standard gauge railcars could now directly enter the Yard from anywhere in the country, delivering materials more quickly and reliably.

The Navy also purchased its own steam "switcher" locomotives for this rail system. These locomotives were designed to switch the order of cars in railyards and were well suited for moving cars short distances within the Navy Yard. The standard gauge rails also allowed the Navy to operate locomotive cranes to assist workers in hoisting material and ship components.

Lastly, the new steam equipment also required a new space for maintenance as well as personnel with experience in locomotives. This led to the conversion of part of Building 105 into a maintenance shop for the Navy Yard's railroad.

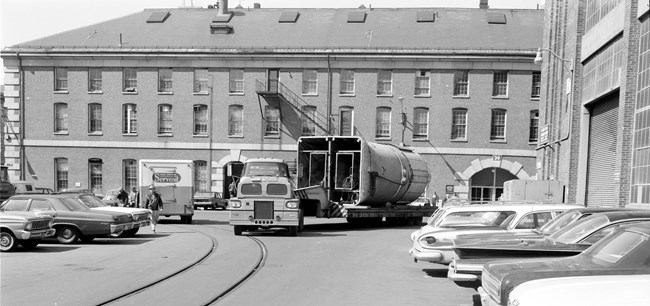

Boston National Historical Park, BOSTS 8972-67

Dieselization

Albert Mostone, an unemployed workshop foreman from private railroad companies, found work at the Navy Yard in 1937 to keep the steam locomotives running. As he remembered it in an interview 40 years later:

My job at the time was to repair the locomotives; bring them out on road and test their brakes which were operated by steam, and any other repairs that had to be made. I worked in the building directly behind the Forge Shop...I worked there about a year, in that building on that job. Then of course they didn't use the steam locomotives anymore. I believe they were scrapped. I had to work on the cranes, which were used to lift the materials from the docks to the ships which were being built or repaired.

Diesel locomotives promised more power, less maintenance, and cheaper operating costs. As a result, the Navy Yard switched from steam to diesel in the yard. But the continued development of this same diesel technology into the 1940s and 50s ultimately led to the decline of the railroad overall. Increasingly powerful diesel trucks, capable of moving some of the heaviest loads at the Charlestown Navy Yard, could do the same work as the railroad without any rails or special infrastructure. The cost savings meant trucks were the future of hauling in the Yard.

Boston National Historical Park, BOSTS 10894-1424

Diesel trucks proved so useful on the Yard by the end of the 1950s that the grand entrance at Gate 1 was demolished to accommodate the truck traffic. During the final years of the Charlestown Navy Yard’s operation, the rail lines in many places fell into disuse.

Now, more than 50 years after the Yard itself closed, rails remain embedded in the ground. They serve as a reminder of the various technological updates the Yard underwent during its 174 years of operation: from transporting materials by animal power to steam and diesel locomotives, to finally replacing the railroad system with trucks.

Sources

Bearss, Edwin C. Historic Resource Study: Charlestown Navy Yard, 1800-1842, Volume II. Boston, Massachusetts: Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, October, 1984.

Bearss, Edwin C. and Frederick R. Black. The Charlestown Navy Yard 1842-1890. Boston, Massachusetts: Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, July 1993.

Black, Frederick R.. Charlestown Navy Yard: 1890-1973, Volume I and Volume II. Boston, Massachusetts: Division of Cultural Resources, Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1988.

Carlson, Stephen P. Charlestown Navy Yard Historic Resource Study, Vol 1-3. Boston, MA: Division of Cultural Resources Boston National Historical Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior, 2010.

Jacobs, Scott, Alane Guitian and Childs Engineering Corp. The Railroad Tracks at Charlestown Navy Yard, Boston, Massachusetts: Division of Cultural Resources, Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1983.