Last updated: January 12, 2026

Article

Boston Massacre

On March 5, 1770, seven British soldiers fired into a crowd of volatile Bostonians, killing five, wounding another six, and angering an entire colony. The event, known as the Boston Massacre, did not happen in an isolated vacuum, but it occurred as a result of growing tensions between Boston colonists and English Parliament.

Prelude to a "Massacre"

At the conclusion of the Seven Years War (1763), England had accumulated a massive military bill – doubling their national debt – and needed to increase national income. The English Parliament settled on taxing their North American colonies and justified the taxes as providing national security.[1] James Otis Jr., Samuel Adams, and others argued that Parliament imposed taxes infringed upon their natural rights as Englishmen. In essence, these Boston leaders wanted to control duties on imports to the town without Parliament interference. The fight over taxes and representation led to violent outbreaks in the streets between Bostonians and royal customs officials. To quell the violence, British soldiers occupied Boston starting in 1768.

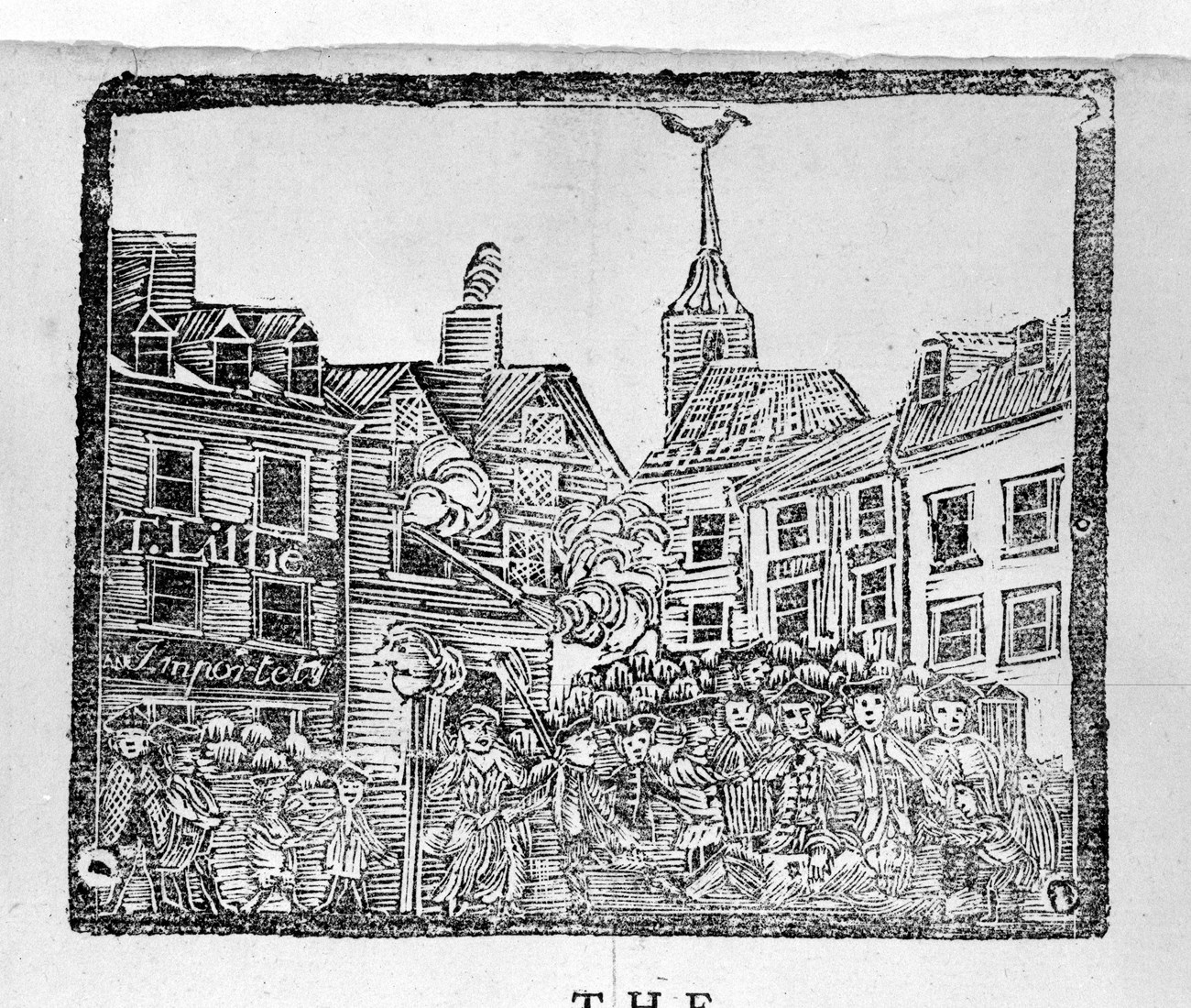

Credit: Engraved by Paul Revere, ca. 1770. Boston Public Library.

The military occupation did little to subdue the rising anger between Boston colonists and British power. Instead of controlling the population, British military presence only exacerbated the issue. An editorial, The Journal of the Times, recorded daily interactions between soldiers and colonists and painted a picture of deteriorating relationships between empire and people.

In one account, on October 29, 1768, British soldiers persuaded "some Negro servants to ill-treat and abuse their masters, assuring them that the soldiers were come to procure their freedoms."[2] To those in Boston, an attack on slavery was an attempt to undermine the local social hierarchy, incite racialized violence against Boston whites, and reaffirm Bostonian fears of becoming enslaved by the British Crown. Other conflicts escalated into physical altercations between the colonists and soldiers.

On January 24, 1769, the editors of The Times described a fight between several officers and town watchmen after the officers had "beat and wounded…very cruelly" an inhabitant of Boston.[3] The violence extended beyond engagements between colonists and soldiers. In other instances, open conflict erupted between colonial supporters (who became Patriots) and British supporters (Loyalists).

The most notable episode of this conflict cropped up over non-importation – the belief that colonies could dictate English policy by reducing goods purchased from England. Boston merchants and consumers who did not adhere to non-importation became political targets and risked open hostilities against themselves and their property. In February 1770, a group of young boys attacked the shop of Theophilus Lillie. Ebenezer Richardson, a patron of Lillie's shop, attempted to clear the street but only provoked the crowd more. As Richardson retreated home, the group called Richardson an "Informer" and berated him with verbal assaults. At Richardson's home the crowd grew. Richardson attempted to disperse the crowd by threatening to fire upon them with his rifle. The crowd did not retreat, and Richardson fired birdshot into the crowd, hitting Samuel Gore and Christopher Seider. Seider, an eleven-year-old boy, died from his wounds.

Collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

March 5, 1770

Tempers cooled, temporarily, following Seider's death and life in Boston continued. The evening of March 5, 1770, began normal enough. It was a cold frigid night. A light snow covered the streets and walkways. Many residents escaped the cold indoors and British soldiers took to their barracks. Private Hugh White, scheduled for sentry duty, took his position outside the Custom House on King Street just beyond the Town House.

The quiet of the night soon turned as colonists, almost as if signaled, took to the streets looking to agitate British soldiers into some sort of irreversible action. In multiple places throughout Boston, groups of colonists came into conflict with British soldiers – near the Liberty Tree, down Boylston's Alley, near Murray's Barracks, and at Dock Square – but the greatest conflict occurred on King Street.

Engraved by Paul Revere. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Colonists surrounded Private White, hurling insults and objects at the sentry who called out for reinforcements. Hearing this plea, Captain Thomas Preston led a small cadre of soldiers to rescue Private White. By this time, a large number of colonists had encircled the soldiers and they could not leave their place outside the Custom House. Insults and objects continually fell upon the soldiers until one shot rang out in the night. An eerie silence followed.

The silence was broken by a volley from the British Regulars tearing into the colonists. Panic ensued and the people fled. The soldiers – Hugh Montgomery, James Hartigan, William McCauley, Hugh White, William Wemms, Jon Carroll, Matthew Kilroy, William Warren, and Captain Preston – remained rooted and gazed upon this "massacre." After a few cautious moments, Preston marched the eight soldiers back to the Main Guard. They took up position outside the State House and were again surrounded by Bostonians who returned and demanded action against Preston and the soldiers. Governor Thomas Hutchinson soon adhered to their demands and ordered Preston and the soldiers arrested.

The Immediate Aftermath

With British soldiers in jail, the Boston Massacre took upon a new struggle. Over the next nine months Boston colonists and British soldiers argued over March 5. They debated the events of the night and its larger significance to not only shape eighteenth-century public perception but define the Boston Massacre for future generations.

Engraved by Paul Revere. Library of Congress.

The battle for public perception began on March 8. Samuel Adams, a member of the Sons of Liberty, led a funeral procession for the victims of the Boston Massacre. Witnesses suggest 10,000 people (approximately 67% of Boston's population) attended the funeral of Samuel Gray, Samuel Maverick, James Caldwell, and Crispus Attucks, the first four victims of the massacre.[4] In this political move, Adams consciously guided the procession through Boston using pageantry to vilify British oppression – festering since the early 1760s – and promote colonial unity over British usurpation of rights. The procession ended at the Granary Burying Ground where Gray, Maverick, Caldwell, and Attucks were laid to rest in the same burial plot. Seven days later, a fifth victim of the massacre, Patrick Carr, was also interred in the plot.

With the victims laid to rest, attention now turned to the soldiers in prison. Bostonians wanted Captain Thomas Preston and the seven soldiers tried and convicted quickly, but Governor Thomas Hutchinson delayed. Finally, in October, Captain Preston took the stand.

Footnotes

[1] Two tax policies passed by Parliament were the Sugar Act and the Stamp Act. To find out more, visit Britain Begins Taxing the Colonies: The Sugar & Stamp Acts & Anger and Opposition to the Stamp Act.

[2] Oliver Morton Dickerson, ed, Boston Under Military Rule, 1768-1769, as Revealed in A Journal of the Times. (Boston, MA: Chapman & Grimes, 1936), 16.

[3] Oliver Morton Dickerson, ed, Boston Under Military Rule, 1768-1769, as Revealed in A Journal of the Times. (Boston, MA: Chapman & Grimes, 1936), 54.

[4] Eric Hinderaker, Boston's Massacre, Cambridge, MA: (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017), 226.

Works Referenced

Archer, Richard. As If an Enemy's Country: The British Occupation of Boston and the Origins of Revolution. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Hinderaker, Eric. Boston's Massacre. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017.

Morgan, Edmund & Helen M. Morgan. The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Zobel, Hiller B. The Boston Massacre. New York, NY: W. W. Norton and Company, 1970.