Last updated: October 7, 2021

Article

Amazing Cave Critters Up-close

Introduction

Caves are not only geologic wonders but also provide habitat for an amazing collection of cool critters, from bats to salamanders and crayfish, to crickets, spiders and bacteria (yep, they’re alive too!) Cave critters are categorized by how much of their lives are spent below ground and the more time spent in the dark, the more dramatic the adaptations.

Cave Critter Lifestyles

Trogloxene—Cave Guest

Organisms, like bats, bears and other creatures, that may only live a part of their lives inside of caves are called trogloxenes (troglo = cave, xenos = guest). Almost all trogloxenes must go to the surface or to the cave entrance for food. They have no special adaptations to the cave environment and can even live their entire lives outside of caves.

Troglophile—Cave Lover

Some critters can spend their entire life underground or on the surface. They are called troglophiles (troglo = cave and phileo = love). They too have no special adaptations to the cave environment. While people who love to go caving, love caves and have no physical adaptions to caves, they are trogloxenes and not troglophiles!

Troglobite—Cave Adapted

Fulltime cave dwellers, called troglobites (troglo = cave, and bios = life), have amazing adaptations that allow them to live permanently in completely dark, low-energy environments. Visual cues within a world of complete darkness have little value and thus many troglobites are colorless, blind and even eyeless. With low-oxygen air in some caves and months without food, some critters have developed super-slow metabolisms and because they live slowly, they also live longer. Some cave crayfish have been found to live up to 50 years! Other organisms shift to utilizing whatever resource is most prevalent in the cave for their food source, such as bacteria that consume hydrogen sulfide.

Adaptations to such specialized environments are possible because cave critters don’t roam far from home. While surface and subsurface habitats are connected in many ways, individual caves are often highly fragmented and separate from one another. Thus, most cave species have small populations, restricted ranges, and low rates of reproduction. Even though individual species population's may be limited, cave critters can be found all over the world, including in caves on both publicly and privately-owned lands. Therefore, there are many different agencies, organizations, and individuals that play a role in caring for these underground worlds and their inhabitants.

Conserving Cave Habitats

The National Park Service (NPS) has the awesome responsibility of managing unimpaired for this and future generations some of the most spectacular landscapes and their inhabitants (including caves and cave critters), as well as cultural sites that tell important stories. The NPS also collaborates with partners to extend the benefits of natural and cultural resource conservation with local communities across the country, such as through the National Natural Landmarks Program. Partnerships formed through this program create opportunities for the NPS to work alongside other land stewards to support their efforts to conserve nationally significant sites. These sites are owned by a variety of public and private entities (most of them are not located within units of the National Park System) and are designated as National Natural Landmarks (NNL) by the Secretary of the Interior in recognition of their outstanding biological or geological resources, including caves!

Considering the often remote, difficult to access nature of their homes, seeing cave critters is somewhat akin to stepping foot on the moon; it is an unlikely event for most folks. These factors increase the importance of understanding and protecting these critters as much as possible so that we can raise awareness, inspire appreciation, and spark curiosity for additional learning. This article shines a virtual flashlight on some truly amazing inhabitants from National Park System and NNL caves across the country, starting off with critters that are big enough to actually be seen with the naked eye!

Let's Meet Some Cave Critters

Northern Cavefish

Donaldson Cave System NNL, located in Spring Mill State Park, Indiana, hosts the Northern Cavefish (Amblyopsis spelaea). This white – almost clear – eyeless fish is king of the limestone cave river systems it inhabits, even at just 4-5” long! These fulltime cave dwellers feed on small invertebrates and even other cavefish and can live up to 30-40 years. With limited populations found only in Indiana and Kentucky, this state protected species receives special attention from local land managers to help ensure protection of its habitat.

Texas Blind Salamander

From blind fishes to blind salamanders, Ezell’s Cave NNL in south-central Texas is home to the Texas blind salamander (Eurycea [=Typhlomolge] rathbuni). This endangered species is found only within water-filled caves of the Edwards Aquifer, a geographically limited area near San Marcos. As with the Donaldson cave fishes, Texas blind salamanders are also eyeless. Without a need for vision, these troglobites eyes are reduced to two small black spots under its skin. And although white or colorless in appearance, bright red, external gills protrude from the throat and are used to get oxygen from the water.

Grotto Salamander

A related species, the grotto (or Ozark blind) salamander (Eurycea spelaea) can be found in the Tumbling Creek Cave NNL in southern Missouri. An unusual characteristic of this cave critter is that that they are fully sighted at the larva stage, however they lose both sight and pigmentation after they metamorphosize into adults.

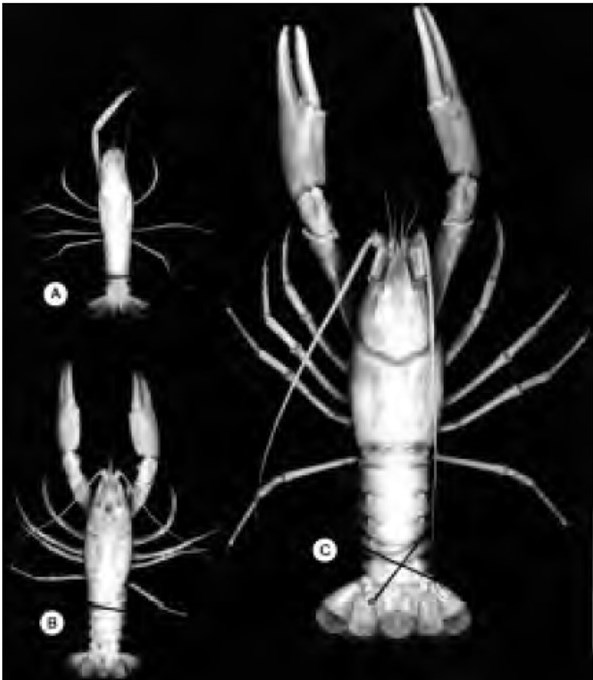

Cave Dwelling Crayfish

Shifting from soft bodied critters to crustaceans, critters who wear their skeletons on the outside of their body (exoskeletons), we go in search of crawdads (crayfish). Just as salamanders can be found in surface waters or solely in subsurface waters like caves, the same can be said for crayfish. Similar to troglobitic salamanders, troglobitic crayfish also tend to lack pigment (color) and are often sightless. One of the roughly 85 species of cave dwelling crayfish (Orconectes genus) is the Shelta Cave crayfish (Orconectes sheltie), which is known to occur only within the subterranean streams and pools of the Shelta Cave NNL of northern Alabama.

Insect—Troglobitic Dipluran

Arthropods also have their skeletons on the outside and include spiders, centipedes, millipeds and insects. There are many different arthropods that can be found in caves. Crickets and beetles are just a few of the many insects that might call caves home, some parttime, some fulltime. Exploring deep into the depths of Lava Beds National Monument in Northern California, one may come across a troglobitic dipluran. Lacking eyes, this pale silverfish looking insect is equipped with two tails, or cerci, extending behind their abdomens to help them feel their way around.

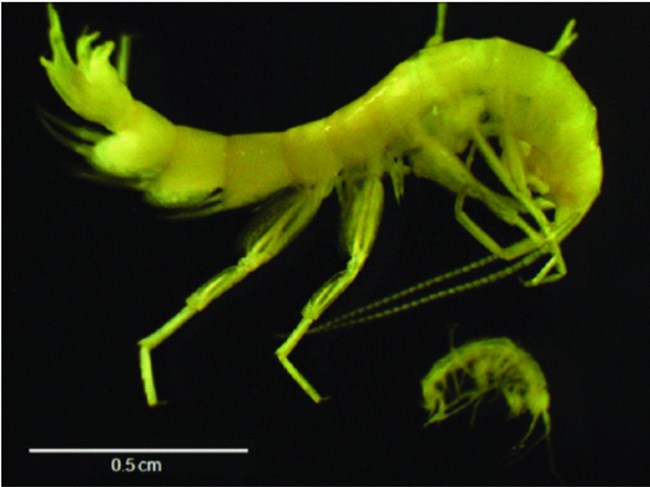

"Ice Bugs"—Allegheny Cave Amphipod

And while most might equate bugs, and caves, with warmer temps, neither is always the case. Some caves are warm, some are cold, and some are so cold they have ice in them. Even more amazing is that Ice Bugs (also called Ice-Walkers) can live in caves made of ice. Grylloblattodea are a small order of ancient and primitive insects, so old they are considered living fossils. Their eggs can hatch in a few months or as long as 3 years. Ice bugs can take up to 7 years to mature. Because they normally live in temperatures between 30 and 39 degrees Fahrenheit, they can die from overheating if you even hold them in your hands.

The Allegheny cave amphipod (Stygobromus allegheniensis), found in caves in New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and West Virginia, is another example of cave bug specially adapted for cold and ice. Ellenville Fault Ice Caves NNL, within Sam’s Point Preserve in southern NY, is host to this small, eyeless, shrimp-like critter. Its amazing ability to survive periods of being completely frozen in solid ice is a necessary attribute for surviving in harsh conditions, where ice and snow fill up their cave each winter.

Blood Red Worms

What about non-arthropod invertebrates (animals without an exoskeleton or even a backbone)? Yep, those can be found in caves as well! In fact, a new species of worm, a blood-red worm (Limnodrilus sulphurensi) to be exact, was recently discovered living in the small stream running through the Sulphur Cave and Spring NNL in northern Colorado. This worm feeds on the bacterial mats that grow in the stream bed. Surviving in a place called “Sulphur Cave”, it makes sense that these worms have an unusual blood system that allows them to thrive in water with high concentrations of sulfuric acid.

Cave Microbes and Bacteria

Finally, as we go down the visual scale of cave critters, we come to the “unseeables”, those living organisms (bacteria and other microbes) that require Superman’s vision or a microscope to observe. These “invisible” cave critters play important roles in cave environments. Just as on land, the base of the food chain starts with the smallest of life. Cave microbes and bacteria utilize elements available within caves, such as the rocks and minerals or hydrogen sulfide, as their energy source, which in turn becomes energy for higher level cave organisms when consumed and can contribute to cave formation. Back at Sulphur Cave and Spring NNL, some curious cave formations called snottites (or cave snot) have an uncanny resemblance to nasal mucous. These mucous-like soda straws hang from the cave's ceiling and contain bacteria that metabolize the hydrogen sulfide, excreting sulfuric acid, which then dissolves the calcite-rich travertine that is host to the cave.

Cave microbes also harbor information valuable to us surface dwellers. Research at Lechuguilla Cave (Carlsbad Caverns National Park) and elsewhere is revealing that microbes found there might produce chemical agents that could be developed into new medications that could be used as antibiotics or even cancer treatments for people.

Many microbes that are found only in caves are considered extremophiles, because they live under extreme environmental conditions such as limited food sources, live in super cold or super-hot temperatures, or even in areas with very acidic water. Some microbes use the minerals found in rocks as a food source. As they digest the rocks for life giving nutrients, they leave behind material called rock flour (or as one microbiologist likes to say “microbial poo”).

Help Protect Cave Critters

The fascinating, diverse world of cave critters is just one of the many aspects of cave and karst resources being celebrated throughout the world as part of the International Year of Cave of Karst. Adapted to survive in harsh, particular environments, often times cut off from other systems, many cave critters are the epitome of specialization. Many are species of concern, are threatened, or endangered. Special care and management, of both the underground resources and the above-ground worlds to which they are inextricably tied are essential to their survival. Any actions that help protect water, air, wildlife, and natural spaces on the surface, such as planting native flowers, limited or avoiding fertilizer, and driving less also help protect the magnificent critters inhabiting the worlds beneath our feet. When visiting caves, be careful of where you walk, stay on designated trails, avoid playing with the cave critters (you may be scaring them!) and don’t leave behind trash. What are steps you can take to help?