Part of a series of articles titled A Great Inheritance: Examining the Relationship between Abolition and the Women’s Rights Movement.

Article

A Great Inheritance: Reflected Shortcomings in Abolition and the Women's Rights Movement

This article is part of a series, "A Great Inheritance: Examining the Relationship between Abolition and the Women's Rights Movement" written by Victoria Elliott, a Cultural Resources Diversity Internship Program (CRDIP) intern at Women's Rights National Historical Park.

It is a disservice to consider the abolitionist movement for all of its triumphs and none of its problems. It is likewise naïve to consider the positive influences of abolition on the women’s rights movement without acknowledging the negative. The following is an examination of the problems within the abolition movement and how these issues are reflected in the early women’s rights movement. Though they fought for the emancipation of slaves, abolitionists were guilty of many grievances against those they sought to free. In comparing the early women’s rights movement to the abolition movement, the same problems of paternalism, exclusion, and objectification of African Americans as present in the abolition movement likewise arise in the women’s rights movement. As noted by bell hooks, “the 19th century women’s rights movement could have provided a forum for black women to address their grievances, but white female racism barred them from full participation in the movement.”

This statement is not made to claim that the white women’s rights movement’s failings existed solely because of abolition. Rather, this comparison is drawn in an attempt to reflect upon the deep roots of racism and exclusion present even in radical movements. Another important note is that this comparison is specifically draws connections between the white abolition movement and the early white women’s rights movement. This in no way means to ignore or erase the equally important African American involvement in abolition and the women’s rights movement. In examining the writings and actions of white abolitionists and the white early women’s rights movement, this series seeks to draw attention to the continuous discourse of racism and exclusionary practices of Euro-Americans towards African Americans present in white dominated branches of reform movements.

White abolitionists began to encourage the participation of African American men in their societies in the 1830s and endorsed the “eradication of caste restrictions against Negros.”[116] However, this declaration proved difficult to practice. Although the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) admitted African American men as members, African American members were restricted in their capacities. It was unusual for African American men in the AASS to be involved in the organization’s decisionmaking processes or to hold offices within the organization. “Moreover, no Negro was allowed to address the AASS annual meeting until 1839."[117] Even within the abolitionist movement, African American men faced exclusion.

Such practices of exclusion against African American women were also witnessed within the women’s rights movement. Rosalyn Terborg-Penn cites the separation between black and white women’s groups as a result of different concerns held between the groups and previous experiences of white prejudice against black women in woman’s groups.[123] One documented attempt to exclude African American women from the early white women’s rights movement is captured by the reception of Sojourner Truth at women’s rights conventions. At the 1851 Woman’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, white women attendees begged the chairman, Frances D. Gage, to prevent Truth from speaking before the crowd. These women were concerned that “Every newspaper in the land will have our cause mixed with abolition and n[---]rs.”[124] Not only did these supporters of women’s rights wish to prevent the black Truth from participating, they also were loathe to connect the women’s rights cause with abolition and African American women. [Note: it was at the Akron Convention that Truth gave her famous "Ain't I a Woman" speech.]

In their fight to free enslaved African Americans, abolitionists used the image of the slave as a symbol to promote their cause. The popular abolitionist emblem of the supplicant slave, represented as both man and woman, helps to illustrate this point. The emblem shows a kneeling African American man or woman in chains. With their hands raised upwards in prayer, the African American figure pleads for someone to unlock their chains. This emblem was featured on various paper products as well as on coins, cameos, medals, crockery, and products sewn for antislavery fairs.[125] Such imagery was popular in poetry, novels, and short stories. In such literature, more often than not, white abolitionists saw African Americans as symbols of oppression and degradation rather than as people.[126]

In a response to a letter the editor, which criticized the lack of support for the 15th Amendment on the side of some of the women’s rights supporters like Stanton and the Revolution, Stanton defended her views, and that of the paper.[128] She posed part of her argument against the 15th Amendment as being in support of African American women: “as an abolitionist we protested against the enfranchisement of the black man alone, seeing that the bondage of the women of that race, by the laws of the south, would be more helpless than before... What to her the loosing of the white man’s chains, if the ignorant laborer by her side, who has learned no law but violence... is henceforth to become her master?”[129] Here Stanton arranged the image of the African American woman to support her argument. Stanton’s racist imagery casts African American men as violent figures and presents the image of the free African American woman as the image of vulnerability, invoking imagery of the supplicant woman slave. Her argument follows that African American women are victims who require the vote to ensure their safety from African American men. By claiming concern for the plight of African American women, Stanton uses African American women to support her argument against the 15th amendment.

While white abolitionists in word sought to eradicate slavery and ensure equality for African Americans, their total efforts were mostly limited to the plight of slavery itself, as many white abolitionists saw African Americans as symbols of exploitation rather than as people subjected to misuse.[130] According to Nell Painter, “free blacks in the antislavery movement had to remind their colleagues of their own situation, for the cause of the slave seemed so much more romantic and attractive.”[131] Northern abolitionists “often felt a horror and disapproval of slavery as an institution, and a revulsion... or discomfort- when actually confronted with blacks on a personal level.”[132] In other words, while many abolitionists desired the emancipation of the slaves, they were less concerned with achieving equality for free African Americans.

Likewise, the women’s right movement limiting their ideas and concerns to the concerns of white women. The mentality of the white women’s rights women was eventually defined as being that white educated women’s rights should be addressed first. As noted by bell hooks, reform efforts put forth by black and white women’s groups were fairly similar. However, African American women had to address problems that were foreign to white women’s experiences, such as the social conceptions of immorality and sexual deviancy among all African American women. “The antebellum white women’s rights movement did not speak to the needs of black women, and some women’s rights leaders even ignored their poorer white sisters.”[133] According to Shirley J. Yee, this attitude had existed amongst white feminists “from the beginning-” at the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, “the issues addressed by the delegates held little relevance for most black women’s lives.”[134] Later, with the proposal of the 14th and 15th Amendments in 1869, the issue of the vote for African American men and not women, this point was solidified.

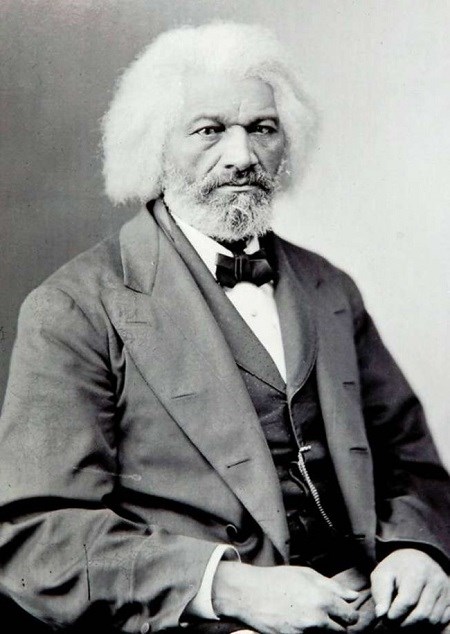

Conflicts over the exclusion of women’s suffrage from the amendment led to divisions between women’s and African American suffrage supporters. Women suffragists who opposed the amendment due to its exclusion of women (like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony) attacked African American men as unfit candidates for the vote. The statement of Frederick Douglass from the American Equal Rights Association proceedings in 1869 point to this stress. At this convention Douglass rose in defense of African American men’s suffrage:

When women, because they are women, are hunted down through the cities of New York and New Orleans, when they are dragged from their houses and hung upon lamp posts; when their children are torn from their arms, and their brains dashed upon the pavement; when they are objects of insult and outrage at every turn; when they are in danger of having their homes burnt down over their heads; when their children are not allowed to enter schools; then they will have an urgency to obtain the ballot equal to our own.[135]

When questioned about the truth of this statement when applied to Black women, Douglass replied “Yes, yes, yes. It is true for the Black woman but not because she is a woman but because she is Black!"[136] Regrettably, Stanton and Anthony and other white feminists were unable or unwilling to acknowledge the difference between the lives of white women and the lives of African Americans.

The relationship between abolition and the women’s rights movement can be most easily summed up as that of parent and child. Many aspects of the women’s rights movement are sourced from the abolition movement. Unfortunately, the failings of the white abolition movement- the failure to see African Americans as people rather than symbols, the failure to address issues faced by free African Americans, and exclusionary practices towards African Americans in the abolition movement- reemerged in the early white women’s rights movement.

Notes:

[116] Friedman, Lawrence J. Gregarious Saints: Self and Community in American Abolitionism, 1830-1870. Cambridge University Press, 1982, pp. 161.

[117] Ibid. pp. 163.

[118] Swerdlow, Amy. “Abolition’s Conservative Sisters: the Ladies New York Anti-Slavery Societies, 1834-1840.” Yellin, Jean Fagan and John C. Van Horne, The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women’s Political Culture in Antebellum America. Cornell University Press, 2018. pp. 34.

[119] Yee, Shirley J. Black Women Abolitionists: A Study in Activism 1828-1860. University of Tennessee Press, 1992, pp. 91.

[120] Ibid.

[121] Ibid. pp. 92.

[122] Ibid.

[123] Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn. “Discrimination Against Afro-American Women in the Woman’s Movement, 1830-1920.” Sharon Harley, Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, The Afro-American Woman: Strugges and Images, Black Classic Press, 1997, pp. 21.

[124] Truth, Sojourner. Narrative of Sojourner Truth; a bondswoman of olden time, emancipated by the New York Legislature in the early part of the present century; with a history of her labors and correspondence drawn from her "Book of life.” Battle Creek, 1878, PDF. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

[125] Yellin, pp. 7.

[126] Williams, Carolyn. ‘The Female Antislavery Movement: Fighting Racial Prejudice and Promoting Women’s Rights in Antebellum America” The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women's Political Culture in Antebellum America, edited by Jean Fagan Yellin, John C. Van Horne, Cornell University Press, 2018, pp. 167.

[127] MacDaneld, Jan. “White Suffragist Dis/Entitlement: The Revolution and the Rhetoric of Racism.” Legacy, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 244.

[128] Ibid., pp. 249.

[129] Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. "Sharp Points." Revolution. 9 Apr. 1868, pp. 212-213.

[130] Williams, pp. 167.

[131] Painter, Nell Irvin. “Difference, Slavery, and Memory: Sojourner Truth in Feminist Abolitionism.” Yellin, Jean Fagan and John C. Van Horne, The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women’s Political Culture in Antebellum America. Cornell University Press, 1994, pp. 154.

[132] Williams, pp. 167.

[133] Harley, Sharon. “Northern Black Female Workers: Jacksonian Era.” Harley, Sharon and Roasyln Terborg-Penn, The Afro-American Woman: Struggles and Images. Black Classic Press, 1997, pp. 15.

[134] Yee, pp. 140.

[135] Stanton et al. History of Woman Suffrage. Vol 2, 1881, pp. 382.

[136] Ibid.

Tags

- belmont-paul women's equality national monument

- frederick douglass national historic site

- reconstruction era national historical park

- women's rights national historical park

- abolition

- women's history

- african american history

- political history

- civil rights

- anti-slavery

- religious history

- suffrage

- international relations

- underground railroad

- ohio

- reconstruction

- 15th amendment

- 14th amendment

Last updated: December 10, 2020