Part of a series of articles titled A Great Inheritance: Examining the Relationship between Abolition and the Women’s Rights Movement.

Article

A Great Inheritance: Abolitionist Practices in the Women's Rights Movement

This article is part of a series, "A Great Inheritance: Examining the Relationship between Abolition and the Women's Rights Movement" written by Victoria Elliott, a Cultural Resources Diversity Internship Program (CRDIP) intern at Women's Rights National Historical Park.

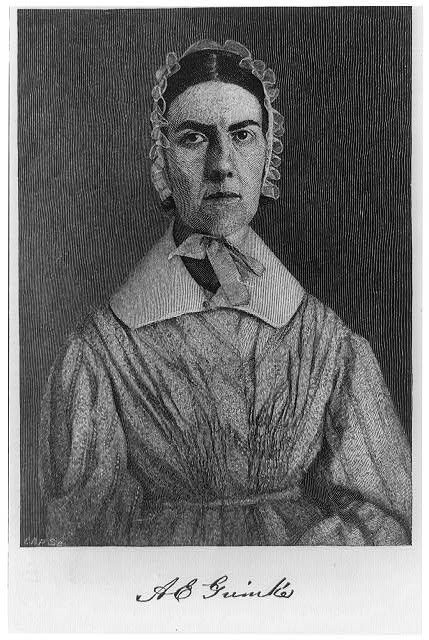

Library of Congress (http://rs6.loc.gov:8081/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=rbaapc&fileName=05000/rbaapc05000.db&recNum=0)

As previously mentioned, some abolitionist women found the confidence needed to reject social conventions and participate in public activities by denying the authority of clerical rules. Abolitionist feminists also found resolve to contradict gender roles in the abolitionist belief of the common humanity of all people. The belief in common humanity was used by abolitionists to argue for the definition of African American slaves as people, not property.

Women who engaged themselves against slavery in the early 19th century called upon themselves and others to identify with black female slaves in the shared experience of womanhood. Antislavery literature described enslaved women’s experiences of degradation and attributed many sins to the slave-woman’s situation, such as immodesty and illegitimacy. In such literature, white slave-owning women were also negatively affected by slavery as the practice changed “otherwise pleasant, humane, white women into monsters of cruelty, encouraging indolence among this pampered class.”[44] Slavery, therefore, was cast an unchristian practice that led women within the system to vice. As 19th century women were the frontline of attack for remedying social immoralities, such immorality begged outrage and action on behalf of their fellow women. By acting for the case of antislavery, then, northern women could fulfill their moral duty for their southern sisters.[45]

This sense of sisterhood was also formed between members of the anti-slavery movement. Women formed local and international networks through the establishment of female antislavery societies. Lucretia Mott, for example, acting as PFASS corresponding secretary, interacted with other anti-slavery societies in Britain and the Unites States.[49] Such connections strengthened female relationships and forged a sense of community in womanhood. In addition to correspondence, female antislavery societies were also brought together through the practice of holding anti-slavery fairs. Women from various anti slavery societies would create and send their goods to the anti-slavery society holding the fair, which created and maintained networks of women organizations. [50] American female anti-slavery societies even sought goods from British female antislavery societies, from imitation fruit to velvet stools and knit goods.[51] These fairs brought in the majority of the income needed to support anti slavery societies, and fostered women’s awareness of their own powers and ability to affect change.[52]

Women abolitionist activities affirmed the power of women to enact social change on a political spectrum. Along with anti-slavery fairs and public speaking, women abolitionists worked in petition campaigns. The practice of petitioning was weaponized by radical abolitionists in the 1830s. By 1837, antislavery petitions were organized on a national scale. The House of Representatives received so many antislavery petitions that Congress passed “gag” rules to prohibit discussion of the petitions and of slavery. New England women were particularly effective at organizing and sending anti-slavery petitions to Congress. The Liberator reported that petitions issued by women in New England doubled that of their male counterparts. “In petitioning, women were far more active than men, as evidenced by the vast number of female signatures on antislavery petitions in comparison to their numbers in the antislavery crusade.”[53] Petitioning would later function as a means of forwarding the women’s rights movement in the struggle for woman suffrage.

In promoting the anti-slavery cause abolitionists acted as agitators who sought to overturn the structure of American society. This marked abolition apart from other movements of its time. While other reform movements fought for change and amendment within American society, Garrisonian abolitionists sought to totally upset America’s structure socially, morally, economically, and politically by calling for the immediate emancipation of the slaves.[54] In 1842, abolitionist and women’s rights activist Lydia Maria Child emphasized the importance of affecting change on multiple fronts: “Great political changes may be forced by the pressure of external circumstances, without a corresponding change in the moral sentiment of a nation; but in all such cases, the change is worse than useless; the evil reappears, and usually in a more exaggerated form."[55] Abolition and women’s rights activists both chose to practice public agitation to reach their goals of achieving both political reform and social change. Women’s rights and the immediate emancipation of the enslaved were both radical ideas which required revolutionary changes in American politics and in public sentiment. The women’s rights movement applied the immediatist abolitionist model of radical agitation to forward their own fight for equality.[56]

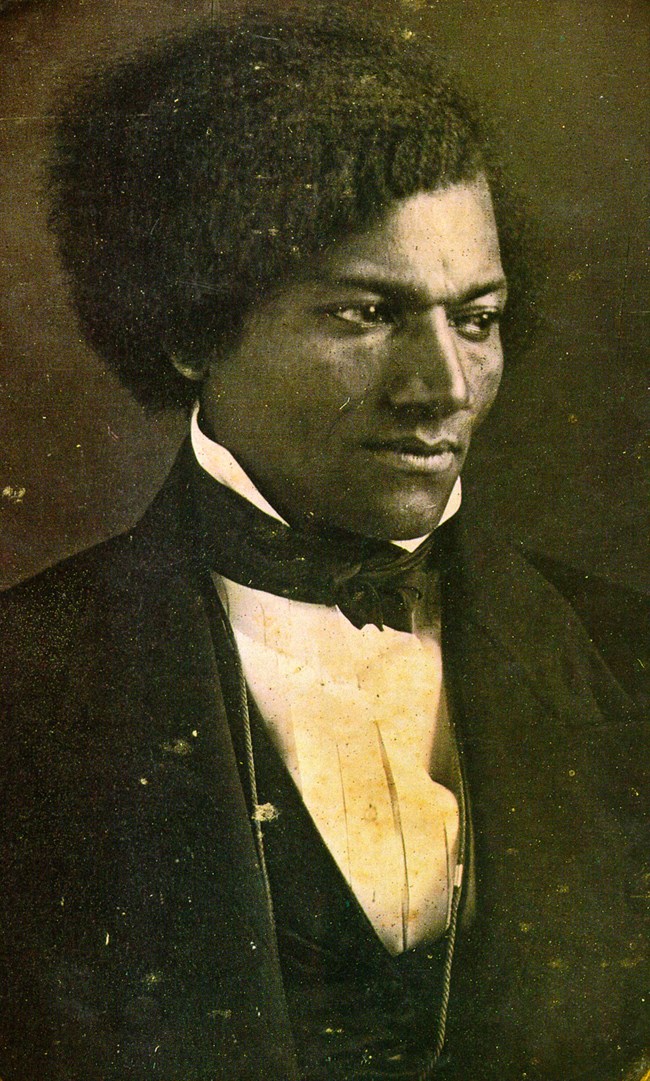

Abolitionist men supported women and gave them a platform to engage publicly for the cause of abolition and women’s rights. The issue of women’s rights was promoted through likeminded abolitionist men such as William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass. William Lloyd Garrison published women’s lectures and promoted women’s rights through his newspaper, The Liberator as early as the mid 1830s, as seen in his publication of Maria W. Stewart’s lectures. In 1838, “the woman question,” or the question of whether or not women should be included in formerly male antislavery societies as members, was rising in prominence within abolitionist circles. Garrison and his followers subscribed to the idea of women’s rights and equality. A Liberator contributor wrote on the issue: “Shall we, when a woman responds aye or no to a proposition which may have come before us or rises, under a conviction of duty, to express her opinion, or to pour out the feelings of her soul in relation to the unutterable horror of slavery, APPLY THE GAG?”[57] For Garrisonian abolitionists, to deny women participation in public activity would be hypocrisy and undermine their claim to the equality of the enslaved.

Frederick Douglass’s abolitionist newspaper The North Star, established in 1847, bore the slogan “Right is of no sex.” Like William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass used his paper to publish in support of women abolitionists and women’s rights issues. Frederick Douglass himself formed strong relationships with feminist abolitionists such as Abby Kelley, Amy Post, and Lucretia Mott.

Although the abolition movement provided support for women’s public engagement, women were exposed to public ridicule for trespassing on the grounds that were considered outside of the woman’s sphere by abolitionists and by the public. In campaigning for abolition, women learned how to refute male supremacy and stand strong in the face of aggression. “White women would be called upon to defend fiercely their rights as women in order to fight for the emancipation of Black people.”[58] Support of anti-slavery was controversial in itself, so women’s active public participation in these programs “naturally created hostility.”[59]

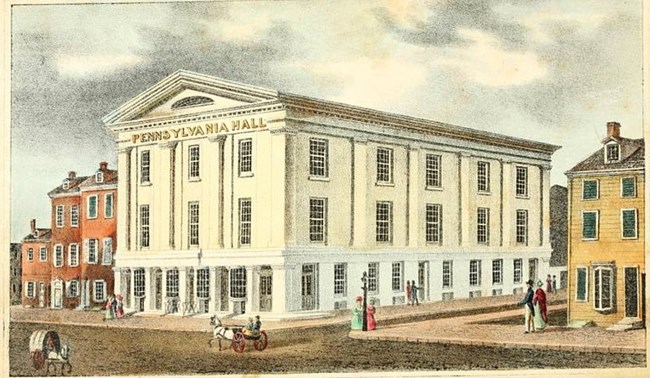

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pennsylvania_Hall_(Philadelphia).jpg

The following afternoon, the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women met and began their meeting with an address to anti-slavery societies, arguing in favor of women’s public involvement in the anti-slavery movement. “We are told that it is not within the ‘province of woman,’ to discuss the subject of slavery; that it is a political question, and we are ‘stepping out of our sphere,’ when we take part in its discussion... May we not permit a thought to stray beyond the narrow limits of our own family circle, and of the present hour?”[64] This meeting was again attended by men and women, both African American and Euro-American. The Hall was surrounded by dangerous mobs, and upon exiting the Hall, the delegates of the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women were obliged to “protect our colored sisters while going out, by taking each one of them by the arm."[65] Later that day, Pennsylvania Hall was burned.

Such instances of aggression and violence against were not uncommon responses to women stepping out of their “sphere,” especially in the case of racially mixed groups as present at Philadelphia Hall. Rather than backing down in the face of adversity, such stalwart women continued to work for the antislavery cause. Such examples of women abolitionist’s resolve provided early women’s rights activists with experience and inspiration to withstand enmity.

Image from a 1905 postcard, public domain. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Exeter_Hall.jpg)

Issues of misogyny at work within abolitionist organizations also impressed upon women an awareness of their oppression that persisted even in radical circles. At the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention held in London, the issue of whether or not women delegates should be allowed to participate in the convention was held to a vote. The men of the convention held voting power, and the decision was made against women delegates' participation. The women delegates were sent to the gallery to observe the convention’s proceedings. Some men left the floor and joined the women in response to this decision. William Lloyd Garrison and fellow abolitionist Nathaniel P. Rogers refused to engage in the convention for its entire 10-day period. Black abolitionist Charles Remond also refused his seat, being particularly indebted to women’s groups who financed his travel to the convention.[66]

The 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention was influential for the women’s rights movement in that it sparked its formal beginning. It was at this event that two key movers in the women’s rights movement first met. Lucretia Mott had attended the convention as a delegate, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton had traveled to the convention for her ‘honeymoon trip.’ The two met at the convention and, according to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, resolved on the necessity of holding a convention to discuss women’s rights.[67] Their idea would not come to fruition, however, until eight years later in Seneca Falls, New York.

Notes:

[44] Melder, Keith E. Beginnings of Sisterhood: the American Woman’s Rights Movement, 1800- 1850. Schocken Books, 1997, pp. 58.

[45] Melder, pp. 58-59.

[46] Davis, Angela Y. Women, Race, and Class. Vintage Books, 1983, pp. 32-34.

[47] Grimke, Angelina. Letters to Catherine E Beecher in Reply to an Essay on Slavery and Abolition Addressed to A. E. Grimke. Boston, 1838, pp. 114.

[48] Davis, pp. 37.

[49] Melder, pp. 66.

[50] Melder, pp. 70-72.

[51] “List of Articles Sent to the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society Fair by the Glasgow Female Anti- Slavery Society.” 15 Nov. 1845, Ms.A.9.2.21.106, Rare Books and Manuscripts Department, Boston Public Library, Boston, Massachusetts. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library.

[52] Melder, pp. 71.

[53] Melder, pp. 72-75.

[54] Kraditor, Aileen. Means and Ends in American Abolitionism: Garrison and His Critics on Strategy and Tactics, 1834-1850. Pantheon Books, 1969, pp. 20.

[55] Child, “Dissolution of the Union” the Liberator, May 20, 1842, as quoted in Kraditor pp. 23.

[56] DuBois, Ellen Carol. Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women’s Movement in America, 1848- 1869. Cornell University Press, 1978, pp. 38-39.

[57] Melder, pp. 98-99.

[58] Davis, pp. 39.

[59] Melder, pp. 67.

[60] Brown, Ira V. “Racism and Sexism: The Case of Pennsylvania Hall.” Phylon, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 130.

[61] History of Pennsylvania Hall Which was Destroyed by a Mob on the 17th of May 1838. Philadelphia, 1838, pp. 117.

[62] Brown, Ira V. “Cradle of Feminism: The Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, 1833-1840.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 102, no. 2, pp.158.

[63] History of Pennsylvania Hall, pp. 117.

[64] Ibid. pp. 131.

[65] Report of a Delegate to the Antislavery Convention of American Women, Held in Philadelphia, May, 1838; including an account of other meetings held in Pennsylvania Hall, and of the Riot. Boston, 1838, pp. 17.

[66] Davis, pp. 48.

[67] Stanton, Elizabeth Cady et al. History of Woman Suffrage. Vol. 1, 1881, pp. 61.

Tags

- belmont-paul women's equality national monument

- frederick douglass national historic site

- reconstruction era national historical park

- women's rights national historical park

- abolition

- women's history

- african american history

- political history

- civil rights

- anti-slavery

- religious history

- pennsylvania

- education history

- suffrage

- international relations

Last updated: November 19, 2020