Last updated: February 1, 2024

Article

50 Nifty Finds #38: A Germ of an Idea

A lot of articles have been written about the history of the National Park Service (NPS) arrowhead emblem. Many recycle the same content and outdated information that has largely come from the NPS itself. Challenging the traditional story has revealed new sources of information—and two previously overlooked arrowhead designs—that rewrite the arrowhead origin story.

Contested Design

In 1949 the NPS held an employee contest to design a universal logo to represent the bureau. Dudley C. Bayliss was awarded first place and the $50 prize. Bayliss was the chief of planning for parkways, so it's not surprising that his design featured a road sign with the letters "NPS" forming the mountains and the tail of the "S" becoming a road.

Dudley Chamberlain Bayliss was born July 2, 1905, in Chisholm, Minnesota. After graduating from public schools, he attended Hibbing Junior College. Initially working as a timekeeper at the Oliver Iron Mining Company, where his father was mining superintendent, he became an engineer in the underground and open pit mines. He went on to study architecture at the University of Minnesota, graduating in 1929. He became an instructor in architecture at North Dakota State College, teaching architectural design, free-hand drawing, history of architecture, and other related subjects. In 1933 he was let go during the Great Depression and returned to Minnesota to pursue a graduate degree in architecture.

In December 1933 the NPS offered him a three-month appointment as a technical assistant with the new Historic American Buildings Survey, working under Charles Peterson. In 1934 Bayliss became an architect (and later landscape architect) for the Blue Ridge Parkway development, a project he would continue to work on for the next 30 years. He recalled in a 1971 oral history interview, "I remember when I first started on this parkways work Tom Vint told me, 'I can’t give you much money, but I’ll give you a good title. You can be chief of parkways.'" He held that position in the Branch of Landscape Architecture, within the NPS Division of Design and Construction, until he retired in June 1966. In 1961 the Department of the Interior awarded him its distinguished service award. Bayliss died on September 22, 1977.

Although Bayliss's road sign design won, it didn’t have broad appeal. As Conrad L. Wirth, who served on the selection committee, noted, “It was good and well presented, but it was, as were most of the submissions, a formal modern type. We expected something that told what the parks were about.”

A New Idea

Shortly after the contest ended more ideas were put forth. Cecil J. Doty, regional architect for Region IV, based in San Francisco, recalled in 1989,

There was criticism of the logo that had won the competition. [Sanford] Hill, Dr. Neasham, myself, and others made suggestions for a new one. I do not remember who suggested using the arrowhead. Being the historian, I suppose it was Dr. Neasham.

Although we don't know what the other suggestions were, Doty's recollection was accurate. Regional Historian Dr. V. Aubrey Neasham, also with Region IV, came up with the initial arrowhead concept. Because of an earlier working relationship with NPS Director Newton B. Drury, Neasham didn't hesitate to reach out directly to share his idea. Speaking on a different topic, Neasham recalled in a 1971 oral history interview, "Being young [and] my old boss serving as director of the National Park Service, I thought nothing of picking up my pen and writing to him as a friend, as a leader." In a December 12, 1949, letter Neasham wrote:

Dear Newton,

This may be the germ of an idea for an NPS emblem. The arrowhead represents history and archeology, and the tree the scenic [views] and the natural [resources]. A good artist may do something with it.

His letter included a rough sketch of a design featuring an elongated arrowhead with a pine tree inside it. Drury thought the design had "the important merit of simplicity" and was "adequate so far as the symbolism is concerned."

Vernon Aubrey Neasham was born August 28,1908, in Reno, Nevada. After his father’s death in 1915, the family moved to California. He attended Berkeley High School, graduating in 1926. He completed a BA in political science at the University of California, Berkeley in 1930. Continuing his studies at Berkeley, he earned an MA (1932) and PhD (1936) in history.

The California State Division of Parks appointed Neasham supervisor of a Works Progress Administration (WPA) research project on California's historical landmarks in 1936. In that position he edited 100 reports that became known as the California Historical Landmark Series. It's also where he worked with Drury, who was acquisition officer for new California state parks before he became director of the NPS in 1940. Neasham began his career with the NPS in November 1938, serving as Region III historian in Santa Fe, New Mexico. His projects included tracing the Coronado Trail in advance of its 400th anniversary and advocating for establishment of Coronado National Memorial. He also studied Fort Union, advocating for it to become a national historic site, and the San Jose Mission in Texas. In July 1942 he became regional historian for Region IV, based in San Francisco.

With men increasingly leaving to serve in World War II, in October 1942 the NPS moved Neasham to acting custodian of Kings Mountain National Military Park and Cowpens National Battlefield in South Carolina. He held that position until the end of March 1944. He enlisted in the US Navy and rose to the rank of lieutenant. He served in Europe, Africa, and South America. He was discharged in February 1946 and returned to his regional historian position in San Francisco.

Neasham left the NPS at the end of December 1952. On January 1, 1953, he became state historian in California's Division of Parks and Beaches, reuniting with Drury who left the NPS in March 1951 to lead that program. Neasham died on March 11, 1982, in Hillsborough, California.

Separating Fact from Fiction

The oft-repeated history of arrowhead design is that when Wirth became director in 1951, he turned Neasham's design over to Herbert Maier who, together with Doty, Hill, and Walter G. Rivers, worked it into the first NPS arrowhead. Wirth himself disputed part of that account in a March 30, 1985, letter. He wrote,

I believe it was the last year that Drury was director we had a superintendent meeting at Yosemite and as we went into the meeting place somebody had placed the big arrowhead at the entrance. Everybody liked it very much better than the one approved as a result of the competition. Either Drury or Demaray made the change. When I became director, I put it to its full use.

Drury received Neasham’s idea in December 1949 and remained director until March 31, 1951. Arthur E. Demaray succeeded him and was director when the arrowhead insignia was formally authorized by Secretary of the Interior Oscar L. Chapman on July 20, 1951. Wirth didn't become director until December 9, 1951. This timeline and Wirth's 1985 letter distance him from any involvement in its creation.

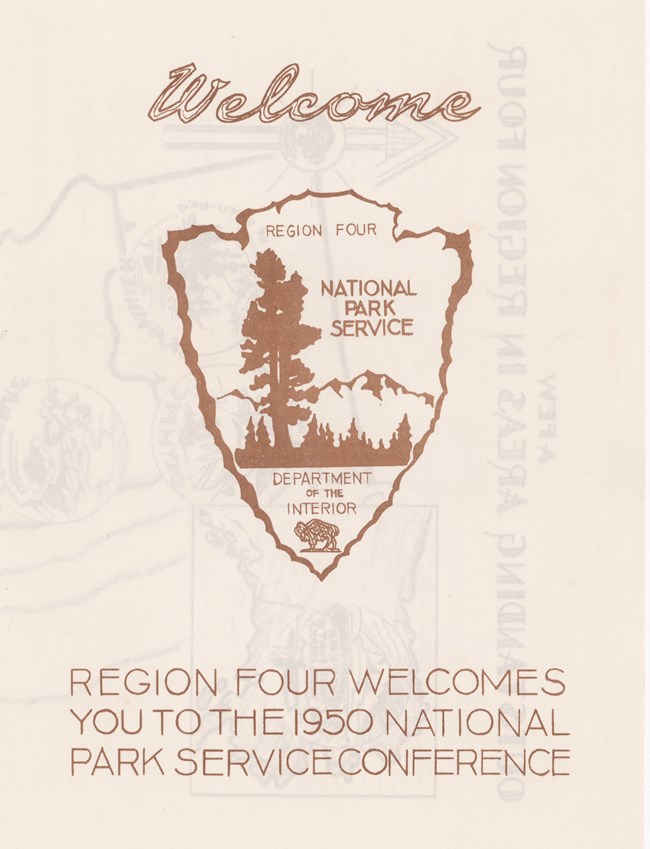

The event Wirth refers to above was the National Park Service Conference, held October 16–21, 1950, at Yosemite National Park. Although the whereabouts of the large arrowhead sign Wirth mentioned are unknown, a drawing of the design in the conference program was recently discovered in the NPS History Collection. It is believed to be the earliest published rendering of what would eventually be developed into the official NPS trademark.

The fact that a recognizable arrowhead with all the major elements existed in 1950 dates its creation to Drury’s tenure, not Wirth's. It's important to note, however, that it was only a welcoming symbol for the conference. The words "Region Four" at the top of the drawing document its limited use. No evidence has been found that Drury directed its creation as a servicewide emblem using Neasham's original idea. Without that documentation, it seems more likely that, following positive feedback from Drury, Neasham, who already worked with regional architects on historic preservation projects, collaborated with Doty, Hill, and Rivers, testing around his initial idea in advance of the conference where it debuted. According to Wirth, it was only after it was praised at the conference that it was developed and refined into the servicewide emblem.

The other oft-repeated story is that the arrowhead was designed by Herbert Maier, an architect famous for the rustic style of architecture in parks before he became an NPS administrator in 1933. On that topic, Wirth was unsure, writing in 1985, “As to who made the arrowhead, I can't say for sure, but I think it was Herb Maier. Everybody has given him credit for it.” Despite the repeated attribution, there is no direct evidence that Maier designed it and much to confirm that he did not.

In recalling how the arrowhead emblem was developed, Doty didn't mention Maier, whom he worked for, knew well, and admired. He did write, “Being the regional architect and having been born in Indian Territory [Oklahoma] I claim to have made the first drawing of the arrow[head].” Doty is almost certainly referring to the 1950 conference emblem.

The NPS History Collection includes oral history interviews with Neasham, Maier, and Doty. Neasham's papers in the collections of the Center for Sacramento History in California. None mention designing the arrowhead. Although Hill and Maier may have had some involvement in initial design ideas in early 1950, they became assistant regional directors on July 1, 1950, and September 29, 1950, respectively, shortly before the first arrowhead was unveiled at the October conference. It seems unlikely that either man had more than an advisory or approval role after they took those regional positions. Interestingly, neither Owen A. Tomlinson, regional director until November 1, 1950, nor his successor Lawrence C. Merriam have ever been mentioned in connection with arrowhead history.

Wirth’s association with the arrowhead’s use is so strong that even Doty didn’t remember that he was not director when it was first approved. He was certain, however, about who was responsible for arrowhead drawings after the initial 1950 effort, and it wasn't Maier. He wrote,

From then on, almost all of the drawings were done by Mr. Walter Rivers. Many drawings were made, and the ones agreed upon were mailed to the Washington Office. Director Wirth approved the drawings—large ones for the entrances and buildings, smaller ones for decals, and even smaller ones for letterheads. All of these drawings were made by Mr. Rivers.

Rivers Runs Through It

Walter Graff Rivers was born February 11, 1914, in San Francisco, California, to parents Walter A. and Eva Graff Rivers. He attended Marin Junior College, and went on to graduate from the University of California, Berkeley with a bachelor's degree in anthropology.

In 1940 Rivers was working at the Schmidt Lithograph Company in San Francisco. He was drafted as a warrant officer on October 29, 1942. Due to a pre-existing health condition, he was discharged on December 4, 1942. Desiring to serve his country and wear a uniform, Rivers joined the NPS as a ranger-naturalist at Crater Lake National Park. His drawings illustrate the park’s September 1948 Nature Notes bulletin. He also worked as a commercial artist.

By December 1948 Dorr G. Yeager, assistant chief of the Museum Division, hired Rivers as a museum curator to work on exhibits in western parks. In that position Rivers was involved in preparing several museum plans and certainly would have known Neasham. In the museum prospectus for Fort Vancouver National Monument (now a national historic site), Rivers envisioned "an archaeological exhibit-in-place at an interesting corner or other point of the original fort." In October 1950, he submitted a museum exhibit plan for Joshua Tree National Monument (now a national park). Although Rivers had been hired by Dorr Yeager, lack of museum funding meant that his salary was paid by the architecture program, which undoubtedly created connections with Doty and Hill.

During the arrowhead design process, Rivers suggested different elements to include, and incorporated ideas suggested by others. Doty’s recollection that Rivers designed and drew all the arrowhead artwork is supported by Rivers family history. Rivers’ son, David, also recalls that his father thought that the final design was “somewhat busy” due to the additional design elements added through this collaboration.

Rivers never recorded who suggested specific design elements or the reasons behind them. Neasham’s 1949 description that the arrowhead represented history and archeology and the tree scenic views and natural resources is the only confirmed symbolism at that time. Later arrowhead revisions came with explanations for the arrowhead, trees, lake, and bison. Regarding the general scene portrayed on the arrowhead, David Rivers notes that the family regularly camped at Manzanita Lake in Lassen Volcanic National Park. His father often sketched that scenery for later paintings. He calls his father's drawings from Reflection Lake across Manzanita Lake to Mount Lassen “a dead ringer for the lake and mountain in the logo.”

Rivers continued to work for the NPS on various planning projects, including one at Muir Woods. It was in this capacity he also drew the preliminary plan for the Fort Columbia State Historical Park in Washington, which was dedicated in 1954. He left the NPS around 1955. He worked as a draftsman for the California highway department.

Rivers was a passionate artist, preferring to paint natural scenes. He remained dedicated to nature throughout his life and was an active member of the Sierra Club. In the 1960s he advocated for creation of Redwood National and State Parks. The February 9, 1978, Congressional Record for the US House of Representatives lists him as one of the many conservationists who fought for preservation and expansion of Redwoods. Walter Rivers died December 21, 1999, in California.

The "Missing" 1951 Arrowhead

An approved design drawing for the first servicewide arrowhead emblem has not been found. It must have existed to get Chapman's approval and as a standard for use. In its absence, a 1952 drawing (discussed below) has been incorrectly described in other histories as the first NPS arrowhead. In fact, the original 1951 design has been "hiding in plain sight" in dozens of NPS reports and brochures.

Rivers' 1951 design featured different mountain peaks, arrowhead edges, and font from his 1952 arrowhead as well as a bison with a long tail and an open lake. Given that Demaray was director when the arrowhead was approved in July 1951, it's not surprising that its first use was in his Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1951 (printed in 1952). Interestingly, it was published with gray design elements on a black background with white accents.

In fact, many park brochures were also printed with black arrowheads in 1952. Examples include Abraham Lincoln National Historic Park (now Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historical Park), Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (as a unit of the National Capital Parks, before it became a national historical park), Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, Capulin Volcano and El Morro national monuments, and Carlsbad Caverns, Crater Lake, Glacier, Yosemite, and Yellowstone national parks. Although the 1952 brochure for Oregon Caves National Monument (featuring a white arrowhead with black design elements) has traditionally been cited as the first document to use the arrowhead, it seems reasonable to assume that the brochures with the black arrowhead—like the 1951 director’s report—were earlier.

Arrowheads in Print

When Wirth became NPS director in December 1951, he did indeed “put it to full use” as he claimed. The emblem was used widely on park brochures, but with little consistency. In most cases it continued to be used with the DOI seal. Despite Doty's reference to Wirth approving smaller arrowheads for use on letterhead, official memoranda from the 1950s and 1960s used only the DOI seal in the letterhead or no emblem.

In 1952 a gray arrowhead with black elements and white accents became common in printed materials. Wirth's Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1952 (printed in 1953) featured that arrowhead, as did park brochures, like Wind Cave National Park and Vicksburg National Military Park. A few park brochures featured other versions of the arrowhead, probably due to printing limitations at the time. Blue Ridge Parkway’s arrowhead was blue, and Casa Grande Ruins featured a white arrowhead with black elements. Some 1952 brochures, like those for Fort McHenry National Monument & Historic Shrine, Zion, Bandelier, and Bryce Canyon, didn’t include the arrowhead at all. By 1953 park brochures routinely featured the gray arrowhead, but other colors continued to be used. Oddly, the 1955 brochure for Theodore Roosevelt National Memorial Park (now national park) and the 1956 to 1959 brochures for Glacier National Park still used the black arrowhead.

During the 1950s and early 1960s the arrowhead color changed often to match the background color of the brochure. The result is a wider range of emblems than is typically presented in histories that illustrate it only with line drawings. By the mid-1960s most arrowheads used in brochures and handbooks featured black elements on a white arrowhead. Although the design itself was largely consistent, the arrowhead used in the 1955 Campfire Training Program Bulletin featured different mountains and text layout. The arrowhead in the 1967 trail guide for Cabrillo National Monument was uniquely redrawn, changing the arrowhead shape and border along with the mountains, trees, bison, and text layout.

Arrowheads in Uniforms

The arrowhead was added to the uniform in the form of a patch on July 29, 1952. Amendment 7 to the 1947 Uniform Handbook stated, "The manual is amended to include the regulations for use of the shoulder patch. An illustration of the recently approved shoulder patch to be worn on the left sleeve of the uniform coats, jackets, and shirts, except raincoats, will be included in a subsequent Manual amendment." A copy of that amendment has yet to be found.

The arrowhead sleeve insignia had different design elements over time (or was better implemented by specific manufacturers), but it was rendered with a white bison, mountains, lake, and letters, with green trees on a brown arrowhead shape. It's unlikely that the white bison was chosen with any consideration of its sacred nature for some Native American Tribes. It's more likely that it continued the use of contrasting white rank elements as seen on the sleeve insignia of the 1920s and 1930s (see 50 Nifty Finds #27 to learn more about early NPS sleeve insignia). There is no evidence that any Native American Tribes were consulted before the arrowhead emblem was adopted. Although it has changed over time, the arrowhead patch has remained a consistent part of the NPS uniform for over 70 years.

In April 1954 Director Wirth issued a memorandum encouraging employees to purchase and wear "the emblem tie-clasp," available in sterling silver or 10-carat gold from the L.G. Balfour Company. He noted the next month that "we are interested in getting the National Park Service emblem recognized and are therefore encouraging its widespread use." To further encourage its use, employees were allowed to wear it on civilian clothes.

Arrowhead Plaques

The first two wooden NPS arrowhead plaques were created by Rudolph W. Bauss in 1952. One of these originals is in the NPS History Collection. Bauss was an NPS model maker who apprenticed as a wood carver in Germany. He went on to become chief of the Museum Branch in 1964. His wooden arrowhead plaques were displayed at the NPS Area Operations meeting held September 4–10, 1952, at Glacier National Park.

Although Bauss painted the bison white, contemporary print materials only featured a white bison if the other design elements were also white against a colored background. Notably, this arrowhead plaque changes the shapes of the snow-capped mountains, the shape of the lake, the level of detail in the arrowhead edges, and the font from the 1951 version. The bison retained its long tail, however. This arrowhead design was also used on the cover of the conference program, suggesting an intent to replace the earlier arrowhead in print materials as well. As documented above, that did not happen on a wide scale.

As seen in the photograph of the original plaque, his bison was problematic because its tail in the print arrowhead didn't translate well on the plaque. This was changed in a new design drawing approved by Wirth on October 22, 1952. Although the designer's name isn't included, based on Doty's recollections it was likely drawn by Rivers. This 1952 design is often cited as the first NPS arrowhead and is why Wirth was given credit in the past for its development. As noted above, the arrowhead in the 1951 director's annual report is earlier and the examples of arrowheads from reports and brochures demonstrate that there was an earlier design that has been overlooked in previous historical reviews. Given that reports and brochures continued to use the first arrowhead design, it is believed that this 1952 design was developed for plaques and other uses.

Most subsequent plaques were thicker than those Bauss created. Therefore, they could represent the knapped edges of an arrowhead by carving rather than with paint. This may explain the need for the arrowhead drawing created in 1954. The arrowhead plaques were used on park entrance signs, buildings, and speaker's podiums at special events.

Historical photographs show little consistency with how the bison was rendered. Many photographs in the NPS History Collection from the 1950s show it outlined in green and standing on green grass. There are a few instances where the bison is colored a solid green. The arrowhead on the Mission 66 sign at Grand Teton National Park features a solid green bison but left off the words “National Park Service” and “Department of the Interior”! A second arrowhead plaque made by Bauss is also in the NPS History Collection. Created in 1964, it is made of resin and features a bison outlined in green.

A 1960 photograph in the Blue Ridge Parkway museum collection features a plaque with white bison standing on white grass. Zion’s museum collection includes a photo of the visitor center in 1966 sporting an arrowhead with a white bison outlined in green standing on green grass. A 1969 photograph of the Brooks River Station sign at Katmai National Monument (now a national park and preserve) features an arrowhead with the bison outlined in white. Another photograph of that same sign, taken in 1975, has a bison with a green outline. Castillo de San Marcos National Monument’s 1971 sign featured a bison with white outline. The arrowhead at the Parachute Key entrance station at Everglades National Park featured a solid white bison in 1972. The plaque on the speaker’s podium used by NPS Director Walter J. Whalen in 1975 featured a bison with a green outline.

These inconsistencies across parks, combined with policies that likely only required replacing arrowheads in poor condition or when signs were updated, make dating NPS arrowheads a challenge, but justify the consistent approach to arrowhead design that started in the 2000s. More research is needed to distinguish policy from practice in use of the early NPS arrowhead logos.

Adopting the Arrowhead

The arrowhead insignia was approved by the DOI as the official symbol of the NPS in 1962. The June 7, 1962, article in National Park Courier announcing it to employees describes the symbolism represented in the arrowhead this way:

The arrowhead "trade mark" symbolizes the scenic beauty and historical heritage of our Nation. The history and prehistory of the United States is recognized in the arrowhead shape of the shield. A tall tree in the foreground implied vast forested lands and growing life of the wilderness. The small lake on the shield is a reminder of the role of water in scenic and recreational resources. Behind the tree and lake towers a snow-capped mountain typifying open space and the majesty of nature. Near the point of the arrowhead is an American bison as the symbol of the conservation of wildlife.

To protect the integrity of the official symbol and prevent misuse or commercialization, the arrowhead was published in the Federal Register in 1962 and then registered with the US Patent Office on February 9, 1965. It is further protected under the Trademark Act.

Towards a Modern Arrowhead

In 1953 Neasham left the NPS to become state historian for the California State Park System's Division of Beaches & Parks. Rivers, it seems, left the NPS by 1955. Hill’s assistant regional director position ended on June 30, 1954, and the next day he became chief of the new NPS Field Office of Design and Construction in San Francisco. He remained in that position until the end of 1965. Doty followed Hill to the new office, eventually retiring in 1968. Doty’s comments in 1989 suggest he didn’t do any subsequent arrowhead design work after Rivers left. Designers and decisions behind modifications to the original design prior to 2001 are poorly documented but likely reflect—at least in part—formats and technologies available at the time.

The few park brochures from 1968 featuring the NPS arrowhead were probably already in press when NPS Director George B. Hartzog, Jr. decided to replace the arrowhead with a new, modern symbol for the NPS (see 50 Nifty Finds #8: Design of the Times). The original 1916 emblem was also removed from ranger badges. The new symbol was unpopular with employees, and Hartzog reversed course before the arrowhead patch was replaced on the uniforms. When the arrowhead was reinstated, however, it didn’t immediately return to park brochures. From 1970 to the 1990s the standard park brochure format didn’t include the NPS arrowhead or the DOI seal. The arrowhead didn't return to park brochures until 1999 when it was added to the black band of the Unigrid brochures.

The arrowhead was redrawn in 2001 by the Dennis Konetzka Design Group. Modern printing techniques allowed for more details and a broader range of colors, even when printing on a small scale. The background color is brown, the trees dark green, and the lake and letters white. Instead of standing on a small patch of grass, the white bison stands amid a field of green. The symbolism of the different design elements was documented at that time. A complementary suite of art for signs and other media was generated in 2004 by NPS Harpers Ferry Center for Media Services.

Sources:

--. (1950, February 02). “Real Tourist Attraction.” The Columbian (Vancouver, Washington), p. 14.

--. (1954, June 23). “Fort Columbia Park Dedication Set Sunday.” Longview Daily News (Longview, Washington), p. 1.

--. (1962, June 7). "Arrowhead Symbol Adopted by National Park Service." National Park Courier, p. 8.

--. (1982, May). “NPS Arrowhead Designer Dies.” Courier: The National Park Service Newsletter, p. 6. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV. Available digitally at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/courier-may1982.pdf

Birth, death, marriage, census, and military records available on Ancestry.com

Allaback, Sarah. (2000). “Chapter 6: Cecil Doty and the NPS Tradition” in Mission 66 Visitor Centers: History of a Building Type. National Park Service, Washington, DC. Available online at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/allaback/index.htm

Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645). Letters from Conrad Wirth and other documents in the uniform research files. NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Bayliss, Dudley C. (1957, July). “Planning Our National Park Roads and Our National Parkways,” Traffic Quarterly. Available online at Planning Our National Park Roads And Our National Parkways (npshistory.com)

Crater Lake National Park. (1948, September). Nature Notes, Volume XIV, No. 1. publications. Available online at http://npshistory.com/nature_notes/crla/nn-vol14.htm

Doty, Cecil J. (1989, July). “Letters.” Courier: News Magazine of the National Park Service. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/courier-v34n7.pdf

Holecko, Sabrina. (2023, December 6). Pers. comm. with Nancy Russell, archivist for the NPS History Collection, regarding content of the Vernon Aubrey Neasham Papers at the Center for Sacramento History. Holecko reviewed his correspondence and Region IV materials but found no reference to the arrowhead or key people involved in its development.

Hussey, John and Rivers, Walter G. (1948, December 9). Proposed Fort Vancouver National Monument (Preliminary Tentative Outline). National Archives, San Bruno, California. Box 289, File 0-32.

National Park Service. (1991, May 1). Historic Listing of National Park Service Officials. NPS, Washington, DC. Available digitally at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/tolson/histlist.htm

National Park Service. (2004, January 7). NPS Graphic Identity Standards. Harpers Ferry, WV.

NPS Oral History Collection (HFCA 1817). Interviews with Neasham, Doty, and Maier. NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Rivers, David. (2023, November 08). Pers. Comm with Nancy Russell, archivist, NPS History Collection, regarding his father Walter G. Rivers.

Rivers, Walter G. (1949, December). Fort Vancouver National Monument Project Museum Prospectus. National Archives, San Bruno, California. Box 291, File 620-46 Museum.

Workman, R. Bryce. (1991). National Park Service Uniforms: Badges and Insignia. Harpers Ferry Center, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Tags

- abraham lincoln birthplace national historical park

- arlington house, the robert e. lee memorial

- bandelier national monument

- blue ridge parkway

- bryce canyon national park

- cabrillo national monument

- capulin volcano national monument

- casa grande ruins national monument

- chesapeake & ohio canal national historical park

- chickamauga & chattanooga national military park

- colonial national historical park

- crater lake national park

- devils postpile national monument

- el morro national monument

- fort mchenry national monument and historic shrine

- glacier national park

- glacier bay national park & preserve

- joshua tree national park

- muir woods national monument

- oregon caves national monument & preserve

- redwood national and state parks

- theodore roosevelt national park

- vicksburg national military park

- wind cave national park

- yellowstone national park

- yosemite national park

- zion national park

- nps history

- nps history collection

- emblem

- emblems

- arrowhead

- hfc

- design competition

- design concepts

- design and construction

- nps arrowhead

- architects

- historians

- directors

- uniform

- insignia

- patches

- plaque

- san francisco