UAF Archives, Alaska and Polar Regions Collections

Note: Dr. Frederick Dean was a career wildlife biologist at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. He conducted wildlife research at Mount McKinley National Park during the late 1950s and at Katmai National Monument during the 1960s. He also headed the Cooperative Park Studies Unit’s Biology and Resource Management Program between 1972 and 1983, and in that capacity he spearheaded a variety of studies of both existing and proposed national park units. Jane Bryant and Frank Norris interviewed him at his Fairbanks home on April 14, 2005.

What brought you to Alaska?

I was born in Boston and spent most of my early life in Connecticut, Vermont and upstate New York, in the Adirondacks. I did my Bachelors and Masters at the University of Maine in Orono; I finished up the masters in ’52 and [then] went over to [the] College of Forestry at Syracuse [for the Ph.D.]. I worked on muskrats; in the Adirondacks [there were] lots of muskrats. I finished up class work and field work in ’54. Then along came an opening, and subsequently an offer, from the University of Alaska Fairbanks as an assistant professor.

What were you teaching at UAF at the time?

Wildlife. I was the only person teaching under-graduate wildlife courses at that point. Back then the university was on [an] eight month salary, and you were on your own in the summer. And the eight months salary was not that great.

In June of 1957, you arrived at the park, and you began a long term study of the distribution, abundance, and habits of the Toklat grizzly. Did you consult with the NPS on this?

At the time there was very little formal work [being] done on them. Ade Murie had done some really great work as background stuff, but his approach was, I think, a very necessary ground work. But it didn’t go the next step in terms of quantitative data and anal-ysis. So I was hoping that I could build on what he’d started. I talked to people at the park at the time [about it], and they said, “Fine. Come.” And they made cabin space available. I shared a cabin at Igloo with Harry Merriam, a seasonal ranger. The previous winter, I had put in a proposal to the Arctic Institute of North America, and I got probably five or six thousand dollars from them. That went pretty much into family living and fuel for the car, and the cost of getting the car down there, which [involved] putting it on the train and so forth. But the fact that the park was willing to have me do the work and to make the cabin space available was great. I stayed at Igloo for [awhile] and then went over to the ranger cabin at Toklat. And [his wife] Sue was out at Camp Denali that summer with two of the kids.

At this time, you were working with the Alaska Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit. What was this unit?

It was one of a whole series of units that had started up in the late ‘30s. [Jay N.] “Ding” Darling [the head of the U.S. Biological Survey from 1934 to 1936] got the program up and running. These units are basically as a result of a memorandum of understanding between the Fish and Wildlife Service, the University, and [various] state fish and game departments. And the University usually provides some salary. In this case here [in Alaska], it’s been salary for support staff and [for] space. [The] Fish and Wildlife Service details one of their biologists to run the operation. And [at Maine] I had experienced the real benefit of being connected [with this] program. Later on, I used a lot of the back-ground with respect to [the] wildlife unit in developing the nature of the [Cooperative] Park Studies Unit.

When you showed up at Mount McKinley for your initial summer of study, was Adolph Murie there?

No. He came in ’59. And I actually shared a cabin with him at Igloo for part of [that] summer. He was one of [my] idols, right from the word go, when I first ran into his work.

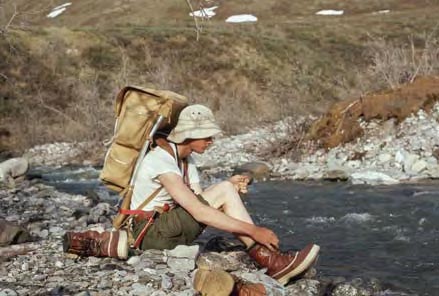

UAF Archives, Alaska and Polar Regions Collection

Did you two have a fairly collaborative relationship?

Yes and no. In ’59, he actually began talking a little bit about maybe [doing] a joint publication and that sort of thing, on the bears, because by then he was focusing pretty much on bears. [But] at some point the whole thing kind of cooled off. I had proposed that we do some tagging of bears in the park [and] use a sub-dermal transmitter that wouldn’t show. And [we would be able to] get that information without intruding more than necessarily on the whole wilderness notion of things. [Ade, however,] just was absolutely against it, and wrote some fairly long letters about it. He just didn’t think that there was a need to do it with respect to what he saw being lost in terms of the wilderness character of the area.

Let’s talk about CPSUs for a while. How did the CPSU in Alaska get started, and how did you get involved with it?

I don’t remember exactly, but I think it was something that Jim Larson [the NPS’s regional chief scientist] proposed, or that he and I, in discussing work I’d been doing at Denali [sic], at some point he mentioned that there was a CPSU program, and that it seemed like a good idea to try and get going up here. Larson, for a while, was working out of Seattle. But, I thought that he’d been in Anchorage for a while too. I think Jim was probably the one that got the thing working up here. I think that … UW [University of Washington, along with] ourselves, and Hawaii were among the very first in the country.

My experience with the wildlife unit structure, I think, had a fairly strong influence in the way it was set up, with a memorandum of understanding, and the contribution from the university and from [the] Park Service. [The] Park Service paid half of my salary on a twelve month basis. The other half of my time was [spent in] a combination of departmental administration and teaching. But the whole situation left me with a lot less teaching responsibility than I had had, and in some ways [the arrangement] benefited both the teaching and the CPSU and research side of things. And that was some of the most productive time I ever had, because I not only had that salary, but I had the administrative help. Given some good assistants, you can get a lot done. And if you get a grad student, for instance, [like] Debbie Heebner [who was] doing her vegetation work, [then] she and the unit’s adminis-trative assistant [were able to] spend two weeks almost full time doing nothing but proof her data. And I had the administrative assistant generally do most of the data entry for things like the big bear bibliographies. On the bibliographies, Diane Tracy collected the basic information and gave it to the assistant. So it was a pretty productive time as far as I was concerned.

A.J. Lynch

So, how did the CPSU work? Did the Park Service approach you about having these various projects done because it didn’t have its own people on the ground in Alaska?

That’s a part of it. [The NPS] didn’t have the staff of scientists that they do now. There was some level of credibility given to having a third party do some of the stuff. And there was the [previously-established] model of the fish and wildlife units [at UAF, for example] that had been so successful. I [helped] convince people up here that it would benefit the parks if they had that opportunity to access the unit with requests for work. It was a two way thing; sometimes we had park people come and say “would you do this?” and other times we would come up with a proposal and sell it. [The CPSU projects were] not related to immediate management problems in the park, but certainly related to under-standing the Park System. But I think we made a pretty conscious effort to try to keep almost everything tied to [NPS] concerns and needs. And when we wanted to get the cabin built out at the East Fork [of the Toklat River, the park] was very definitely supportive of that.

Who was your primary NPS contact – was it Jim Larson or the Alaska-based biologist John Dennis?

I think of Jim Larson as having a lot more interaction administratively than John. But neither one of them was in Fairbanks a lot; maybe two or three times a winter. Most of my interaction would have been [with] people at the park level, and most of that was clearly at Denali. At Glacier Bay, I got involved a little bit when they were doing some science planning for the area, and I went down [to Gustavus] to sit in on a couple of meetings. They already had a pretty good science program going before we got involved. I think the other [Glacier Bay] work was either marine or geological.

Physically, did the CPSU program operate out of the Irving Building [at UAF]?

Yeah, it was operated out of my office and one room in front of it. [Chuckle] But our gradate students, and the faculty members that were working with the unit, were all either faculty members of the department, or associated with it, or in the case of students, they were all graduate students within the department. We did hire some people [such as] Herb Melchior, who worked on the Chukchi-Imuruk program, and a few others that were CPSU employees that were not formally faculty members of the department.

AJ. Lynch

When a typical CPSU study was completed, how many copies would be made and [where] would they go?

Generally there was not a big stack of publications made. [For] most of that stuff, it went to the park areas [and] the [NPS] Regional Office. I think [that for] things like the annual reports, I [probably] sent those to all of the park areas in the state. But on things like the bear bibliography, we made a lot of copies of that, and [for] that whale report, there were quite a few copies made. We did try to have a supply for at least limited distribution after that.

I understand you worked with the Jurasz’s on a controversial whale study. [Chuck and Virginia Jurasz, from Juneau, completed a 1977 CPSU study which assessed the impact of cruise ships on whale behavior in Glacier Bay National Monument.]

The park people had some uneasy feelings about that whale job. And the Jurasz’s admitted that they did not know how to plan their work ahead of time or how to analyze it. [So] I got asked to come in [and] “please do what you can to tighten it up.” They did demon-strate some statistically significant differences with and without disturbance [to the whales]. But what they had was not a randomized sample. And I think some people dismissed the whole thing a lot more than it should have been dismissed. There was some real stuff there, [and] I think [that their findings were] inconve-nient for some people.

And that same sort of thing has been a problem, I think, for some of the Denali stuff. Chief Ranger Gary Brown asked us to do some work when [the park] first started up the bus system, and Diane Tracy responded. [This study, completed in 1977, was called “Reactions of Wildlife to Human Activity Along Mount McKinley National Park Road.”] We had, I think, a good [research] design; it was randomized, riding the bus, making observations [at] different times of day, different days of the week, the whole thing. It would have been nice if she’d had much larger samples. But she had enough on the caribou to demonstrate statistically significant differences in behavior with differences [such as] distance from the road. [But] there have been a couple of studies since then [where there was] basically collecting information from drivers that is not collected in a systematic, randomized fashion. And those more recent studies haven’t come close to [Tracy’s], I don’t think.

Regarding funding, the Park Service must have liked the work that the CPSU did during the 1970s, because each year your budget went up, from $150,000 at first to, at one point up to $550,000.

I know that some of the projects, particularly the Chukchi-Imuruk [now Bering Land Bridge] one, got fairly expensive. Particularly as [we] got involved [in] ANILCA issues, there was quite a lot of work there that added up.

Many of the reports that were completed through your Biology and Resource Management Program dealt with the existing parks and monuments. But [for] several of them—the Chukchi-Imuruk vegetation study, a sport hunting study out in the Wrangells, [and] perhaps two or three others—dealt with areas that were being proposed for new parks. Were these studies of purely scientific interest? Or do you think they were designed with a political purpose in mind – to help, on a scientific basis, determine where boundaries might be?

No, I think that they were requested by the Service as good background information for the proposed areas. And, particularly the work in [the] Wrangells was strictly to do with the hunting in the area and the immediate portions of that area that were being used by sheep and [other megafauna].

Would this study help to determine which parts of the new proposed park should be open to sport hunting and which parts shouldn’t?

Yeah, and also where to draw the boundaries in order to include the land that that population needs on a year round basis.

A.J. Lynch

Were there particular people that went out of their way to lobby for greater funds?

Well, I think that the situation went through a change. Dennis and Larson both, I think, really supported the program very strongly. I know Gary Brown really supported the program from Denali. And the superintendents at the parks; for quite a long time, I had a really good relationship with them. [I could] walk in and say hi whenever I came through, and chat about things, and they seemed to really support it. [But] at some point, after a number of changes of park people, the relationship that I had with [the parks] began to sort of dissolve.

I think the biggest change came after Al Lovaas got involved. [Al was the first Regional Chief Scientist in the NPS’s Alaska Regional Office, which began in late 1980.] He was supportive up to a point, but he told me fairly early on that he’d had some bad experiences with [the] CPSU in the Midwest; I think he was in [the] Oma-ha [regional office].

It was kind of interesting in a way, and frustrating at times, because I felt that the people at Denali and some of the people at Glacier Bay seemed to really understand what we were trying to do and to appreciate what we were doing. But, I often had a feeling, especially in the later years, that the people in Anchorage did not really see much gain from having the unit there. For example, I went on sabbatical and set up a program where I was talking with people in Norway, Sweden, and Finland about the way that they were handling Suomi [Lapp] people inside their national parks, [establishing] what were the conflicts [and] how did they handle them. When I came back, I went down to Anchorage and presented a seminar and suggested [that] the main point of it all was that here is the time to start getting people together and talk[ing] about some of these problems that are going to come up about the use of legal wilderness areas with respect to subsistence and changing technology in particular. And, you know, people were pretty darned unresponsive to this. I think it was not very popular to suggest any regulation of activity by Alaska Natives.At the same time, a couple of other factors were involved I believe. One of them, during the [early 1980s], the Interior Department advisors wanted to control Alaska from D.C. And this was something I was told over and over again, that that they were really trying to keep a tight hand on things. Top-down and with control of the information that shows up. Right about the same time as that, there was apparently an agency change in philosophy, and they began building science programs in the regional offices. It was clear that [Al] was very interested in building up the science staff in Anchorage. When that group of people began to increase and take on more responsibility, the amount of interest in the CPSU was going down. [So] the big factors were the Reagan policy and the development of the science group within the Service in Anchorage.

To see all reports published by the Biology and Resource Management Program, go to www.nps.gov/akso/docu-ments/AKcpsubiblio.pdf

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science- Volume 8 Issue 1: Connections to Natural and Cultural Resource Studies in Alaska's National Parks.

Tags

Last updated: August 10, 2016