Photo by Dan Boone and Ryan Belnap, Bilby Research Center, Northern Arizona University The First PeopleThe human history of the Verde Valley begins around 10,000 years ago, when the southwest was cooler and wetter than it is today. Paleolithic hunter-gatherers traveled through a greener, woodier Verde Valley, filled with pinyon pine, shrub live oak, and juniper. Today we know of their presence from a handful of Clovis points - distinctive stone points that were probably used with spears - that have been found in and near the valley. Clovis points are found all across North America and parts of South America, indicating that these ancient people traveled widely across the continents, probably following game animals, the growth of edible plants, and other resources.

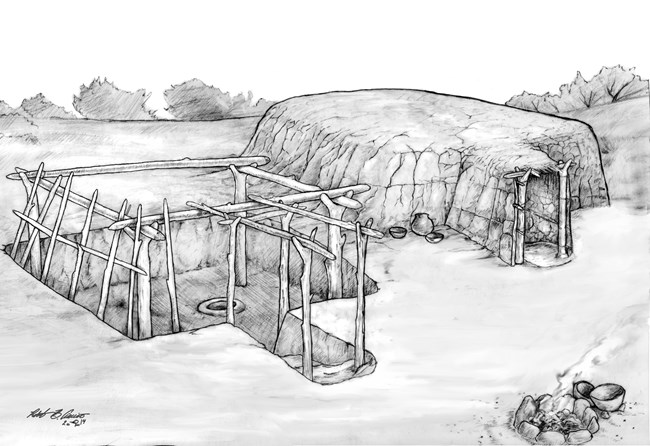

Drawing by Robert Ciaccio via Desert Archeology Inc. The SinaguaAround the year 650, 1400 years ago, people began settling in the Verde Valley. Among the oldest structures found in the valley are the pithouses, partially buried dwellings that were the most common form of housing across the southwest between about 4000 years ago and 600 years ago. Many of the oldest pithouses in the region are found in the Sonoran Desert, south of the Verde Valley near present-day Phoenix and Tuscon. An excellent example of an excavated pithouse can be seen at Montezuma Well. Verde Valley PueblosConstruction of multi-room pueblos began by the year 1000. The pueblo at Tuzigoot is architecturally similar to pueblos that can be seen around the region, like Bandelier National Monument, Aztec Ruins National Monument, and Chaco Culture National Historical Park in New Mexico, Mesa Verde National Park, Yucca House National Monument, and Canyons of the Ancients in Colorado, and many sites along the Mogollon Rim in Arizona, including Wupatki and Walnut Canyon National Monuments, Honanki and Palatki Heritage Sites, Sacred Mountain, and Montezuma Castle. What do these similarities tell us? While there are distinct regional differences, and specific trends and preferences differ from one village to the next, the broad similarities in construction indicate that all of the people who lived in this part of the southwest knew each other and traveled frequently to each others' homes and towns. Skills, information, ideas, and technology traveled freely between the pueblos and people of the Colorado Plateau and desert southwest, and both the objects found here and the construction of Tuzigoot provide ample evidence of this exchange.

NPS

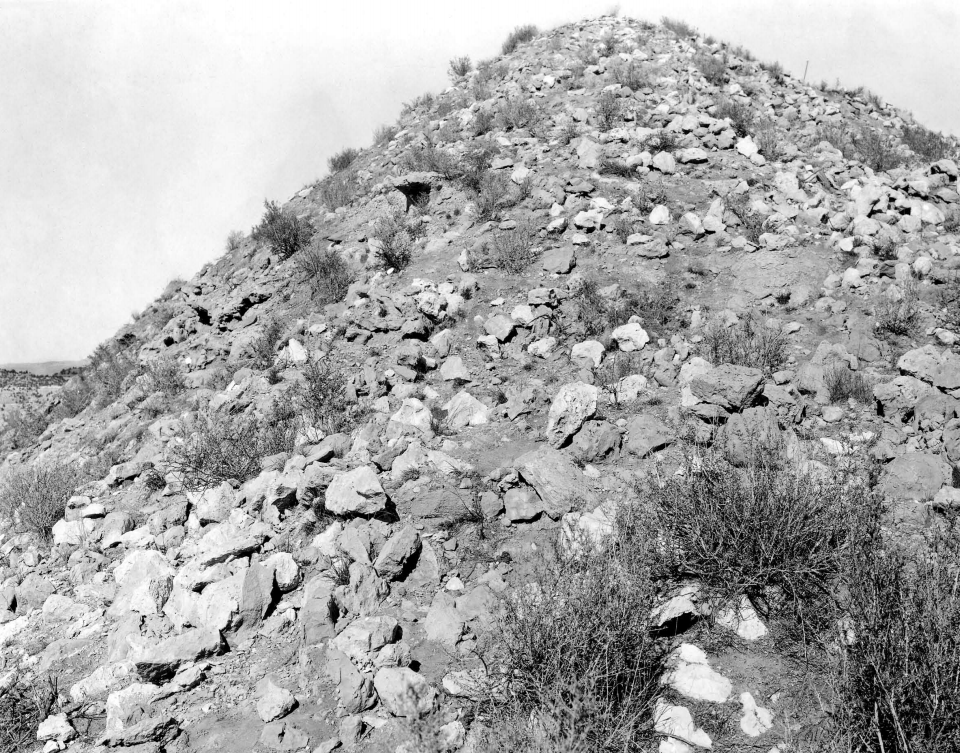

NPS Travel and TradeThe people who built and lived in the rooms of the Tuzigoot pueblo were part of a vast and thriving community, with trade connections stretching from the top of the arid Colorado Plateau to the jungles of Central America and the Pacific Coast. Established networks of roads and trails linked communities across the landscape, and many people built their homes along waterways and at the tops of hills - very much like people still do today! This village was built high on a limestone ridge, over a hundred feet above the floodplains of the Verde River. It has clear lines of sight in every direction, and can easily be seen from many of the other hills - and pueblos - in the area. Tuzigoot was a prime spot to build, with excellent views, easy access to reliable, year-round water, and floodplains where cultivation of water-intensive crops like cotton was relatively easy. Writing in 1895, the archeologist Jesse Fewkes noted During the excavation of Tuzigoot pueblo, trade items and materials from hundreds of miles away were found. Distinctive regional pottery from many different communities across the southwest was found here, as were seashells, exotic minerals and paints, obsidian from distant volcanoes, and feathers from macaws, which are found from southern Mexico into the Amazon basin of South America. People living here probably exported minerals, including azurite, malachite, and copper, as well as salt, cotton, and textiles. Moving OnWhen the time came to leave the Verde Valley, the people were ready. For the Hopi, the Verde Valley villages were stops in a much longer migration to the Hopi Mesas, and were never intended to be permanent settlements. Ancestors of the Yavapai left the pueblos and farms for a more mobile lifestyle of hunting and gathering. The Zuni say that some people remained behind, whether because they couldn't travel or chose not to leave. It's possible that environmental factors influenced the decisions people made to move on in their migrations. The climate was changing in the 1300s; as the Medieval Warm Period ended and the Little Ice Age began, both direct and proxy evidence for climate history indicates that the southwest experienced cooler temperatures and significant droughts. These changes may have been among the signals that it was time for the people in the valley to continue their migrations to the northeast.

NPS Records and Excavations of TuzigootAfter the people departed in the 1300s, the pueblo at Tuzigoot stood above the river for centuries, slowly weathering under the sun and infrequent rains until, by the early 1900s, most of the walls had collapsed. People lived continually in the region throughout those centuries, and no doubt periodically passed by or visited the old pueblo where their ancestors lived. The first documentation of pueblos in the European-American record dates to 1855. Antoine Leroux, a well-known mountain man and trail guide, passed through the Verde Valley in 1854, and reported this the following year:

Caywood and Spicer, 1930s The archeological excavation at Tuzigoot was done between 1933-1935. It was led by Louis Caywood and Edward Spicer, who were both graduate students at the University of Arizona at the time. The name "Tuzigoot" was given to this site during their excavation; tuzigoot is a corruption of the Tonto Apache name Tú Digiz, which is the name for this stretch of the Verde River and is usually translated as "Crooked Water." Like Fewkes, Caywood and Spicer prepared a long and detailed report on their work and their findings. Today, many of the artifacts uncovered by Caywood and Spicer are on display in the Tuzigoot museum collection. Built in 1936, the museum was designed specifically to echo the construction techniques used in the Tuzigoot pueblo. All but a handful of the artifacts on display in the museum were found here on site, and all of them allow us tiny glimpses into the daily life, work, and art of people who built these walls a thousand years ago. |

Left image

Right image

|

Last updated: December 6, 2024