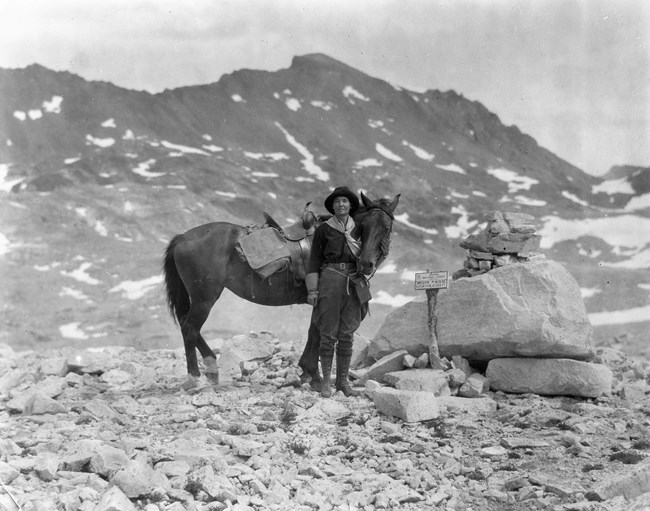

NPS Photo The Golden Twenties rejuvenated the spirit of the United States - it was an era marked by economic prosperity, the rise of commercialism, and the emergence of jazz and social dancing. Perhaps the most significant of all were the advancements made towards women's rights. Women's suffrage, the proposal of the Equal Rights Amendment, fashion, and large-scale entrance into the workforce brought about a newly found liberation for women. Susan Priscilla Thew embodied this newly-found liberation and her enthusiasm and energy left a lasting impact on Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. With little experience but great motivation, 40-year-old Susan Thew left Giant Forest in August of 1923 to explore the rugged terrain of the Sierra. Thew hoped to capture a still untouched landscape in images and words that would make clear the need for its preservation. Little did Thew know that her work would succeed in nearly tripling the park's acreage - making her one of the most prominent female figures in the history of these parks. Susan had originally come to California to escape the harsh Ohio winters with her father, Richard Thew, a wealthy industrialist and inventor. In the summer of 1918, having determined to stay year-round, she drove the rough dirt road to Giant Forest and encountered the beauty and serenity of the sequoias for the first time. Although she only spent a limited amount of time within the park, she was instantly captivated. She soon acquainted herself with the superintendent of the park, Colonel John R. White, and learned of the various efforts to create a greater Sequoia National Park. It was then that the idea of promoting for park expansion began to take hold of Susan Thew and she began her travels into the high country east of Sequoia - the High Sierra.

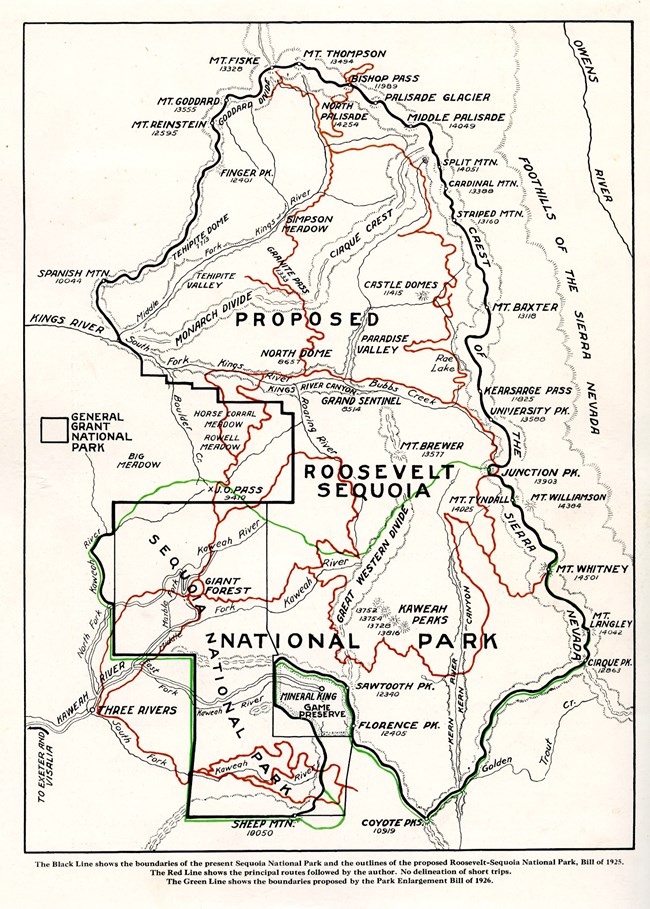

NPS Photo For the next several years, with determination and ambition, Susan applied herself to the campaign to preserve the grand wilderness of the Southern Sierra. She spent several summers traversing some of the most rugged terrain in the continental United States. With one companion and small packtrain, she covered hundreds of miles, photographing the landscape in hopes of conveying something of its beauty. With these images, the largest and most complete photographic record of the region to date, Thew produced a publication for distribution to members of Congress promoting the park idea. Entitled "The Proposed Roosevelt-Sequoia National Park," her gazetteer gave a vivid sense of the grandeur of the land needing protection. Since the founding of Sequoia National Park in 1890, numerous bills to enlarge the park had been introduced, but none had succeeded. Not until the 1926 proposal, when Susan Thew submitted her gazetteer, did an enlargement bill succeed: The park boundaries were extended to include the Great Western Divide, the Kaweah Peaks, the Kern Canyon, and the Sierra Crest. After passage of the bill, the director of the National Park Service sent a telegram to Susan in recognition of her efforts. Although many factors were included in the passing of the bill, her persuasiveness and ardor were undoubtedly the deciding factor in the push for park expansion. Her dedication had paid off.

NPS Photo During the campaign to create Kings Canyon National Park in 1940, Thew's approach was used again. Photographer Ansel Adams created a portfolio of stunning images for distribution among members of Congress and, like Thew, his efforts contributed to success in passing an expansion bill. Throughout her life, Susan Thew remained an advocate for preservation and understanding, but never more so than in her role in the expansion of Sequoia National Park. It was here that Susan found inspiration:

In 1918, Susan Thew discovered something she loved and devoted all her efforts to making a change. She not only found a new source of personal energy in the parks, she ensured that generations to come would have the same opportunity. |

Last updated: October 2, 2023