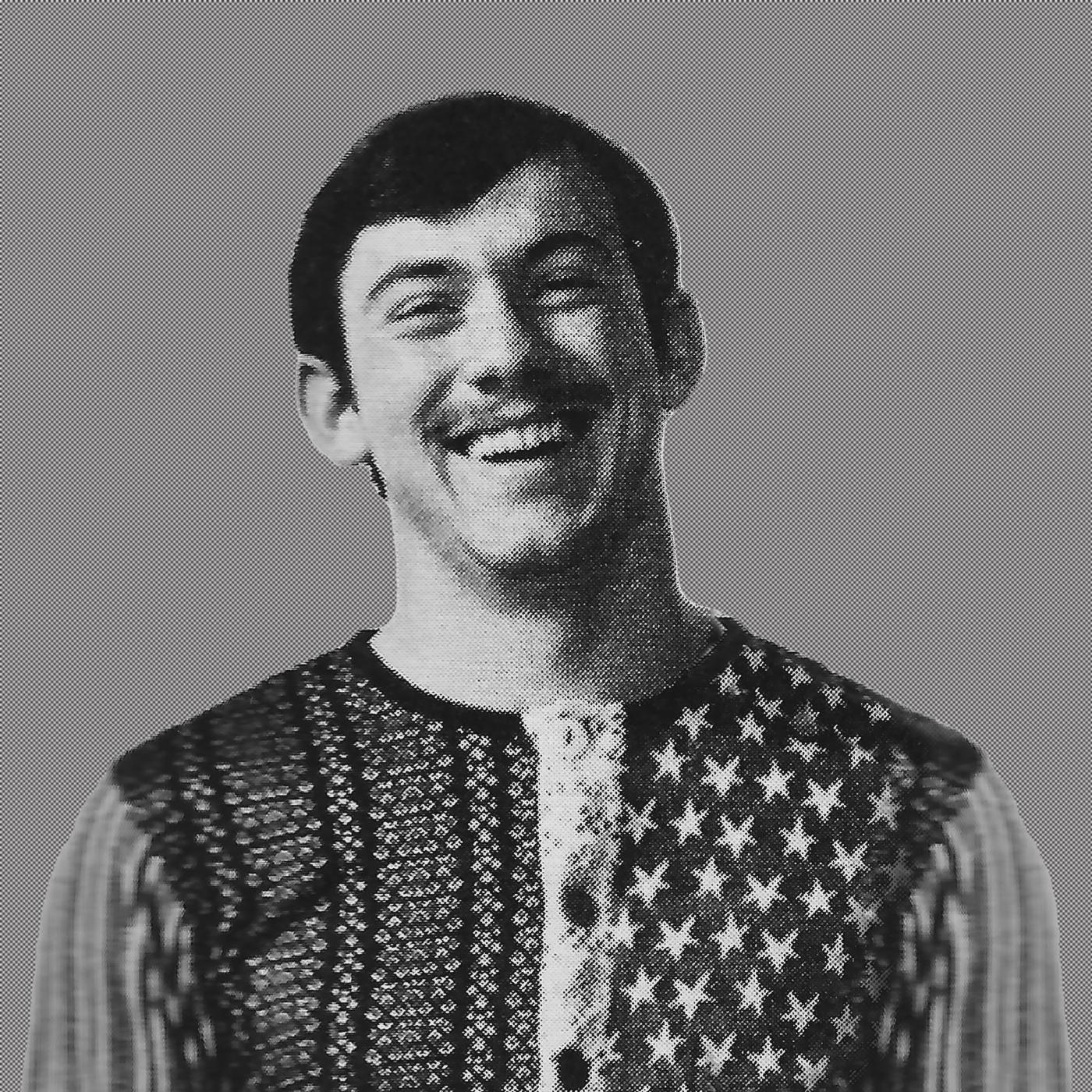

3. Alonzo Plummer (1893 - 1980) Part II

Transcript

David Dollar: Hello again. In case you just joined us. I'm David Dollar. We're going to visit this morning again with Mr. Alonzo Plumber. I think we're going to try to talk a little bit about education this morning. So Mr. Plumber, why don't you take it from there and do what you will with it? Alonzo Plumber: Oh, okay. Well, I'm going back to Nebo again. David Dollar: Good. Alonzo Plumber: There was a typical thing that happened that's probably... You wouldn't, most of you understand the sanitary facilities that had to do with that school, it was very simple and natural. The boys had the north side of the road and the girls, the south side in the woods. This except for the fact that most of them didn't have a creek to use for refrigeration purposes, this was a typical country school. I would say over the south, not just in Louisiana, but over the south. My mother and father realized, they were ambitious for us. And they realized that the facilities there were altogether inadequate. And they had read of this normal school at Natchitoches and decided to move to Natchitoches. So the family moved in 19 and three to 110 Casbury Street there in Natchitoches ... Normal Hill, as it was called at that time. And as Louisiana state normal school didn't have one brick building on it. Every building was a wooden building. The two buildings that housed the classrooms and other educational facilities, one of them was about in the position that the old science building that burned down was in and the other just across the driveway from it was known as a model school. And that model school took in from the beginners up to oh, about seventh or eighth grade. And that was the only school below the normal level, except for a short time, Mr. Greeno ran a private school on... In the position that's now occupied by the parking lot that is provided by the police jury here in this parish. David Dollar: Right? Right. Alonzo Plumber: I came to school here, entered the third grade was a miss Henrietta Lewis as teacher. I think all of us loved Ms. Lewis. She was a fine person. I was in school here for then continuously for five years. We had this advantage and the organization and the school was such that it was in four months terms and there were three, four months terms in a year. And we could go to school 12 months in the year. Well, a part of the time I did that. And the part of the time I worked during the summer, even as a child. David Dollar: This allowed the children to help their parents then doing crops and things like that during the rotation series. Alonzo Plumber: My family lived here in Gnatcatchers. The crop situation didn't come into the picture for us, but it. David Dollar: It did for some others, then. Alonzo Plumber: It did for some of the people. However, I'll say that to emphasize the fact that most of the schools outside of the centers, the wealthier centers of population, or these little one room schools there was at the time and it existed for a number of years after we came here in 19 and three, there was a school that's now on very near where the valley electric company is. That close end operated a one room. David Dollar: Well I'll be darned. Mr. Plumber, let me interrupt you right here. We've got to take a commercial break right now. A little word from our sponsors, the folks at People's Bank and Trust Company. In case you just joined us. This is David dollar. We're visit visiting this morning again with Mr. Alonzo Plumber on memories. Mr. Plumber, we've been talking a little bit about education. Why don't we skip just a few years after you left the normal school here, when you yourself began teaching. Why don't you start there with it? Alonzo Plumber: Well, that was [inaudible 00:06:17] considerably in 19 and eight at the mature age of 15, I was a teacher in one of those little one room schools down close to Bichico in what was then St. Landry Parish. It's now Evangeline Parish. I began the process then, the next year I didn't go to school. And then the following year during the summer, I had ... I happened to be in one of the classes taught by Mr. D.G. Lonsberry, who was superintendent of schools in east Louisiana Parish. Well, the state had become more involved in public education, and they were promoting consolidation of these country schools. So he offered me the principalship of the Bluff Creek Consolidated School in east Louisiana Parish. David Dollar: And how old were you at this time? Alonzo Plumber: I was 17 at that time. David Dollar: 17 and a principal? Alonzo Plumber: That's right. David Dollar: My goodness. Alonzo Plumber: And the faculty, three besides myself, the oldest one of them was 19. And they had come up somewhat in the same fashion that I had. David Dollar: What was one of the reasons that the state was pushing for this consolidated school now? Alonzo Plumber: Well, there were many reasons people could readily see that the one room school was not the answer. The thing that retarded that thing the more was roads and transportation. David Dollar: Transportation. I can understand that. Alonzo Plumber: And they were very, very ... well, in fact, no improved roads, you might say, in the state. In fact, right here in Gnatcatchers Parish. When I came to Gnatcatchers there was not an improved road running into Gnatcatchers. Not a one. I don't mean even a gravel road. David Dollar: Even with the college here? Alonzo Plumber: That's right. David Dollar: Not a road? My goodness. Alonzo Plumber: Not a one. And the original pavement on Front Street was going on, and that was the first piece of pavement in the city of Natchitoches. David Dollar: My goodness. Alonzo Plumber: That was in 19 and three. David Dollar: So you were in about 19... What? Eight or 10 or so? Something like that. You were teaching as well as coming back to normal here, working on your degree, is that true? Alonzo Plumber: Well, we didn't think about degrees then the old normal was not a college and that is it. Wasn't a four year college that offered a degree. But I was alternating teaching ... David Dollar: An education, yourself? Being a teacher and a student and a principal all at the same time? Alonzo Plumber: Yeah, that's right. Going on. David Dollar: That's pretty unique. Let me interrupt you one more time for a commercial message from our sponsors this morning, People's Bank and Trust Company. We'll be right back. Mr. Plumber. We like to close our programs with a closing memory. If you've got something you can share with us, why don't you do that at this time? Alonzo Plumber: This sticks in my memory, I don't know that it's significant from any very ... a great point of view, but I remember a student who felt like always that he was being picked on. And he was a regular problem. The boys wanted to be nice to him, but, you know, they would pick at him a little. And I remember one incident, Victor connected with it. He had got him a new Topco. Very proud of it. And in coming downstairs for a recess period, the boys, a number of them had taken their finger in mark... that is put pressure up and down his back. And the others would say, well, now I wouldn't mark that boy up like that. I just wouldn't ruin his coat by putting praying marks all over it. So he came in tears to me, down in the office telling that tale. And I said, well, and he was sincere in it. I said, now that's pretty bad, but are you sure? I had seen the back of his coat and he had. Are you sure that they did that? Oh, yes. I sure. Well, I had him take off his coat and hanging up on the [inaudible 00:11:39] there in the office was back toward him. And he saw it. Well, he just liked to fainted. David Dollar: Cause he ... Alonzo Plumber: And he had... it brought the whole picture to him about the type of thing that he had been doing that caused him not to get along well with people. David Dollar: Well, I... Alonzo Plumber: And he was pretty much of a changed person. David Dollar: Well, that's great. Things are not always what we think they are. Are they? Alonzo Plumber: They sure are. David Dollar: So that's a lesson that we all could learn. We'd like to, to thank you, Mr. Plumber for joining us again today on Memories. If you folks enjoyed the show today, if you were listening, why don't you let the folks at People's Bank know about it?

Mr. Plummer is a regular guest on Memories. He talks about his time in school, at Normal College (present day Northwestern State). He also discusses his time in elementary school and how it differs from the school schedules today.