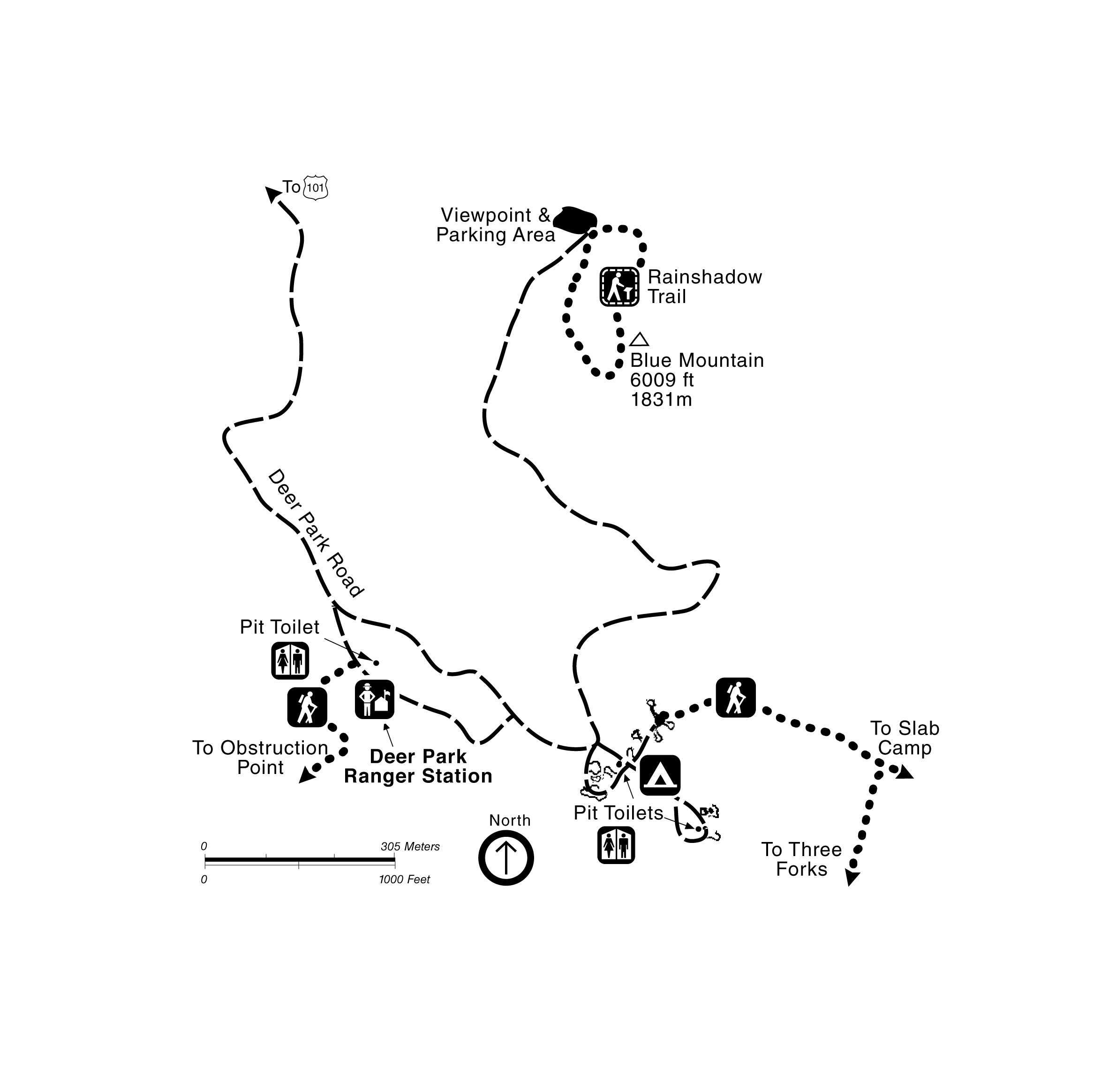

A Sunny ShadowThe Pacific Northwest has a reputation for being dark and gloomy, shrouded in year-long mist. Indeed, the west side of the Olympic Peninsula is the wettest spot in the lower 48 states. But the dry eastern Olympics tell a different story.Much of the area's weather originates in the Pacific Ocean. Storms roll inland from the southwest, heading straight for the Olympics. As the clouds rise over the mountains, pressure and temperature drops, so the air can no longer hold all its moisture. The moisture falls as rain and snow. By the time clouds pass northeast of Mount Olympus and the Bailey Range, they have dropped most of their water resulting in considerably less rainfall, known as a rain shadow effect, on the eastern Olympics. Just as less sunlight reaches the shadow of a tall building, less moisture reaches a mountain's rain shadow. The Hoh Rain Forest can get 140 inches of precipitation a year, but Sequim, just north of Deer Park, gets only around 16 inches! Deer Park InformationNOTE: The 18-mile Deer Park road is narrow and steep with occasional turnoffs. The last nine miles are gravel and are not suitable for RVs or trailers—please use caution. From late fall until late spring when snow melts, the road is closed at the park boundary, about nine miles from Highway 101.Facilities: Deer Park Ranger Station is staffed intermittently during summer and fall. Camping: There are 14 sites, including fire pits with grates, picnic tables, accessible pit toilets and animal-proof food storage. Potable water is not available. Firewood gathering is prohibited. During high wind, watch for falling branches from trees burned by a 1988 fire. Regulations: Pets and bicycles are not permitted on trails. Open fires outside of campground fire pits are not permitted above 3,500'. Backpackers must obtain a wilderness camping permit. See www.nps.gov/olym for more information about permits and reservations. Day Hikes at Deer ParkRain Shadow Loop: This 0.5-mile loop trail to the top of Blue Mountain has panoramic views of lowlands and mountains; elevation gain is about 170'.Deer Park to Obstruction Point: A 7.4-mile trail leads to Obstruction Point through subalpine forests and moutain meadows.Total elevation gain is 2,423' Maiden Peak or Elk Mountain: Prefer something shorter? Try Maiden Peak, 3.5 miles one way with 1545' elevation gain. Another option is Elk Mountain, 5.5-miles one way with 2,249'of elevation gain. These two destinations branch from the trail listed above. Three Forks: This is a strenuous 4.3-mile hike to the junction with Gray Wolf River Trail; elevation loss is 3,416'. Deer Ridge: This trail starts at Three Forks Trail and splits after 0.2 miles. Dropping 650', the first 1.5-miles take you to the park boundary. The trail continues for another 3.1 miles to Slab Camp, in Olympic National Forest; total elevation loss is 3,272'.

Islands in the SkyFor over a dozen plants and animals, the Olympic Peninsula is a very special place. It is their only home—the only place in the world you can find them. Species limited to a specific area are called endemics and are often concentrated on islands—land that has remained in absolute isolation for a long time. Why are there so many endemics in Olympic's high places, like Blue Mountain?During the last ice age, which ended 10-15,000 years ago, the Olympic Peninsula was isolated by glaciers. Glaciers born on high peaks spread into the valleys, and great ice sheets from Canada wrapped around the northern and eastern edges of what is now a peninsula. A low valley full of melting glacial water lay to the south. The higher peaks in the rain shadow were not covered by extensive glaciers. Mountaintops became islands, refuges for plants and animals that were trapped by the advancing ice. Species that survive on such islands are isolated from their counterparts elsewhere and over time may evolve into distinct species or subspecies. No place in the world outside of the Olympic Peninsula can you see the Olympic chipmunk, Flett's violet, the Olympic torrent salamander, or any of the region's other endemics. At Deer Park you can see evidence of the powerful forces that shaped these mountains and their residents. Glacier-rounded foothills below you; endemic Olympic bellflower blooming on the summit. The once common endemic Olympic marmot is rarely seen here now, likely due to non-native coyote predation. The sanctuary of Olympic National Park may help these ice-age relicts survive new threats like the spread of non-native species or human-driven climate change, at least until the next ice age. |

Last updated: November 9, 2021