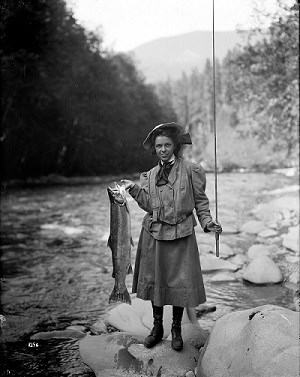

For millennia, the Elwha River ran wild, connecting mountains and seas in a thriving ecosystem. The river proved to be an ideal habitat for anadromous (sea-run) fish, with eleven varieties of salmon and trout spawning in its waters. These fish thrived in the cold, clear waters of the Elwha River and historically served as an important food source for the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe living along its banks.

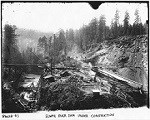

NPS Photo American expansion spurred a continual demand for lumber. The growth of the logging industry in the region brought rapid change to the Olympic Peninsula and specifically to the Elwha River with the construction of two dams. The Elwha and Glines Canyon dams were built in the early 1900s, generating hydropower to supply electricity for the emerging town of Port Angeles and fueling regional growth on the Peninsula. However, construction of the dams blocked the migration of salmon upstream, disrupted the flow of sediment downstream, and flooded the historic homelands and cultural sites of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe. For over a century, the web of ecological and cultural connections in the Elwha Valley were broken - then the river's story changed course. In 1992, Congress passed the Elwha River Ecosystem and Fisheries Restoration Act, authorizing dam removal to restore the altered ecosystem and the native anadromous fisheries therein. After two decades of planning, the largest dam removal in U.S. history began on September 17, 2011. Six months later the Elwha Dam was gone, followed by the Glines Canyon Dam in 2014. Today, the Elwha River once again flows freely from its headwaters in the Olympic Mountains to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Discover Elwha River Restoration

History of the Elwha RiverBeginning with the growth of the logging industry in the early 1900's, the Elwha River experienced powerful changes over the last century. Learn more about the story of the Elwha River from the pre-dam era to the present day.

Dam RemovalLearn about the engineering and mechanics behind the dam removal process and view photos that chronicle the removal of the Elwha and Glines Canyon Dams.

Restoration and Current ResearchThe Elwha River provides a rare opportunity for scientists to learn what happens when a dam is removed and salmon return to a wild, protected river. Read more about restoration and current research.Meet the Olympic National Park partners that helped free the Elwha River.Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe |

Last updated: March 28, 2025