|

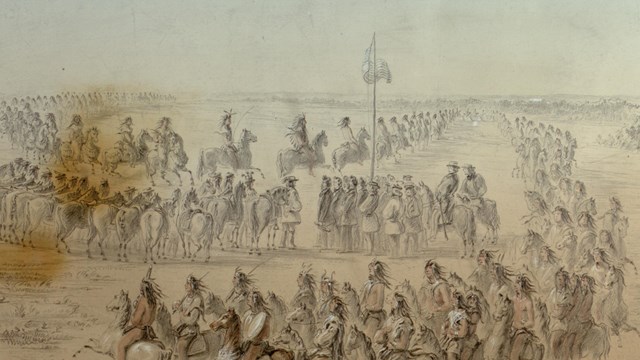

The White Bird Battlefield is the location of the first battle of the Nez Perce Flight of 1877. Roots of ConflictIn the spring of 1877, General O.O. Howard gave the nimíipuu (Nez Perce) who were living outside the boundaries of the 1863 treaty reservation 30 days to relocate. While enjoying their last stretch of freedom at Tolo Lake, a few young warriors led by Wahlitits attacked some homesteads on the Salmon River. Realizing the army would respond to the bloodshed, the nimíipuu bands moved to Lahmotta, one of the homes of the White Bird Band.

The Treaty Era

The Treaty of 1855 designated a portion of the Nez Perce homeland as a reservation, but the Treaty of 1863 reduced it in size by 90 percent.

Old Chief Joseph Gravesite History

The remains of Old Chief Joseph, a leader who refused to sell his Wallowa homeland and sign the 1863 Treaty, were reburied here in 1926.

Dug Bar History

While on their way to the new reservation, Chief Joseph's band crossed the Snake River on May 31, 1877 and lost several heads of cattle.

Tolo Lake History

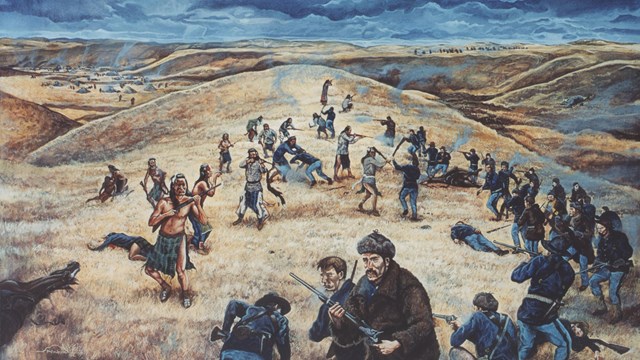

When the non-treaty bands met on June 2, 1877, before moving onto the reservation, three Nez Perce warriors raided homesteads in the area. The Battle at White Bird CanyonJune 15Captain David Perry, commanding officer of the First Cavalry, was sent from Fort Lapwai to investigate reports coming from the Camas Prairie with orders to arrest the perpetrators of the Salmon River raids and escort the remaining Nez Perce to Lapwai. Perry led 106 cavalry men from Companies F and H, accompanied by eleven civilian volunteers. Upon arrival, Perry was told the Nez Perce had left Tolo Lake for White Bird. June 16Pressed by settlers in Grangeville, Perry continued his advance on the evening of June 16. By this time the nimíipuu lodges could be seen along White Bird Creek. June 17, DaybreakNimíipuu scouts kept watch on Captain Perry's column as it moved deeper into the canyon. As Perry advanced, the alarm was raised in the camps. Despite having taken advantage of whiskey that was liberated from local homesteads, the nimíipuu responded. Close to seventy warriors participated in the battle. June 17, Opening MovesLieutenant Theller's scouting party came across this ridge, and far down the canyon they saw wisps of smoke marking the location of the nimíipuu encampments along White Bird Creek. As Theller took stock of the situation, he noticed a nimíipuu peace party approaching, flying a white flag. Arthur 'Ad' Chapman, a volunteer came up to Theller's position or close by and for reasons that cannot fully be explained, opened fire on the peace party. The nimíipuu responded and bullets began to fly. Before Theller could give instructions to his Trumpeter, John Jones was shot and killed by Otstotpoo or Firebody, adding to the initial confusion. June 17, The Critical MomentThe volunteers, led by George Shearer, responded to that first shot by leaving the main column and heading toward the village. As they approached the heavily wooded White Bird Creek, the volunteers began to receive heavy fire from the nimíipuu, driving them back to this knoll. The volunteers may have only stopped here briefly before continuing their retreat back up the canyon. Seeing the volunteers run had a demoralizing effect. Some of the troopers in Company F interpreted the withdrawal of the volunteers as an order to retreat. Perry was quickly loosing control of his command. June 17, Company H Joins the FrayAs Captain Perry attempted to sort out the deployment of Company F, upon hearing the rifle fire, Captain Joel Trimble ordered Company H to assume a position on the far right of the Perry's line on the ridge top. June 17, McCarthy's PointAs Captain Trimble deployed the men of Company H, he sent a detachment of six men led by Sergeant Michael McCarthy to this bluff to protect the rear and far right flank of soldier's position. As the thin line of soldiers began to break and pull back from the ridge top, McCarthy left his position, but was ordered back by Captain Trimble. McCarthy remained on the bluff to support a stand that never materialized; McCarthy was left behind. He evaded nimíipuu warriors combing the battlefield for weapons and made it to Grangeville two days after the battle. June 17, RetreatUnable to stem the nimíipuu advance, Perry's command split into two groups. Captains Perry, Trimble, and a small number of men retreated up the steep sides of the canyon. Lieutenants Theller and Parnell followed the wagon road they had descended earlier that morning. Theller and seven men went off the road into a ravine and became trapped and were killed; Parnell's group survived. AftermathAs Perry gathered his shattered command at Mt. Idaho, he left behind thirty-four dead. An additional two soldiers and two volunteers were wounded.

Looking Glass' 1877 Campsite History

The Looking Glass Band joined the non-treaty Nez Perce on July 1, 1877, when their village was attacked by the U.S. Army.

The Nez Perce Flight of 1877

In 1877, the non-treaty Nez Perce were forced on a 126-day journey that spanned over 1,170 miles and through four different states.

Visit White Bird Battlefield

Plan your trip to the site of the Nez Perce Flight of 1877's first battle. Located near Whitebird, ID. Nez Perce Trail Auto TourThe Nez Perce National Historic Trail has developed auto tours with travel instructions for retracing the 1877 route of the Nez Perce along with maps, graphics, and details about the confilct at sites you can see along the way. Download Auto Tour 1 for more details about the battle at Whitebird Canyon and other early events in the Nez Perce Flight of 1877. |

Last updated: December 30, 2022