NPS/Patrick Myers Water is the Lifeblood of Great Sand DunesAs in our own bodies, water is the glue that holds this complex system together, through flowing streams, wetlands, and moisture that allows unique plants and animals to survive in the sand. The impressive dunes and the incredible diversity of life in and around them depend on these life-giving waters for survival. These streams and wetlands are not simply beautiful features of a national park. They are critical parts of a huge natural system that shapes and maintains the Great Sand Dunes as we know them today.

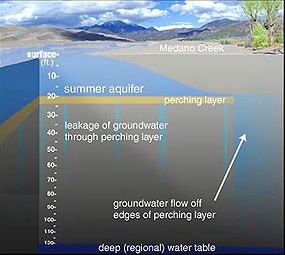

NPS/David Zelenka Walking on WaterWhen you walk on shallow Medano Creek at the base of the dunes, you are walking on water that extends deep below the surface. The dunes sit on top of an aquifer that extends up to a mile below the valley floor. Streams flow on top of the high water table, and most wetlands here are actually the visible top of the aquifer, where it fills in the lowest depressions in the dunes and valley floor. Recharged each year by stream runoff from the mountains, the aquifer is two–layered, with an unconfined upper layer and a deeper layer largely confined by seams of blue clay. Instead of flowing into rivers that eventually reach the ocean, streams flow on the valley surface, then sink down through the sandy soil, primarily into the unconfined aquifer.

NASA/NPS The Heartbeat of the Dunes Larger View of Mountain Creeks Diagram The cradling, flowing arms of Medano Creek on the east and south sides of the dunes, and Sand Creek on the north are the coronary arteries of the Great Sand Dunes. Sand grains blow into the dunes from the valley floor, bouncing up and down over a sea of sand, until they drop into Medano or Sand Creeks. The water in the creeks captures the sand, carrying it back downstream to the valley floor, only to be picked up again by the wind. The wind/water recycling continues, piling the sand to gigantic heights.

NPS/Patrick Myers Streams With a PulseMedano Creek and Sand Creek are unusual in another way. This is one of the few places in the world where one can experience surge flow, a stream flowing in rhythmic waves on sand. Three elements are needed to produce the phenomenon: a relatively steep gradient to give the stream a high velocity; a smooth, mobile creekbed with little resistance; and sufficient water to create surges. In spring and early summer, these elements combine to make waves at Great Sand Dunes.

NPS/Patrick Myers Sunny White Beaches?The high water table supports other geologic features important to the dunes. A sabkha is a whitish plain where sand is cemented together by evaporated salts from seasonal ponds. The sabkha here has developed in the large wetland region west of the dunes. These sensitive wetlands are held at the surface by the high water table, and are subject to sub–surface changes in the aquifer.

NPS/Stephen Trimble Moist DunesDig down anywhere in the dunes a few inches and you will find wet sand anytime of year. The source of this moisture content - 7% throughout the dunes - mostly comes from precipitation captured over time. The dry sand on top actually serves as a moderate barrier to escaping moisture. About 11 inches of precipitation falls on the dunes in an average year, while about 50 inches falls on the high peaks above the dunes, most of which flows down into the valley’s aquifer.

NPS/Patrick Myers Pure and CleanWater quality is monitored regularly throughout the park and preserve. The mountain water in Medano Creek is of such purity that it qualifies under rigid standards for "Outstanding Waters" designation by the state of Colorado. Though the water gains natural salinity as it reaches the sabkha, it remains essentially unpolluted. Streams and ponds throughout the park and preserve provide an ideal habitat for all wildlife, especially for species that are threatened in other areas due to water pollution or disappearing habitat.

NPS/Patrick Myers Ancient WaterRecent research has focused on dating the water at various depths and localities in the park. Carbon-14, Tritium-dating, and other methods have been used to estimate ages of the different waters. By dating the water, scientists can learn how water moves through the dunes system. Water emerging into streams just west of the dunes predates the 1940s, and may be far older. The oldest water in the park, beneath the dunes in the deep aquifer, fell as precipitation before the last ice age.

NPS/Patrick Myers The Past and FutureProtecting this entire natural hydrological system was the driving force in the 2004 expansion of the national monument to a large national park and preserve. In the 1980s and 1990s, commercial water development north of the dunes threatened the entire dunes system. As a result of citizen support statewide, Congress acted, creating a national park and preserve to better protect the system’s waters. Scientific research helped us to initially understand the importance of this hydrological system to the Great Sand Dunes. Research Links Ground-Water Flow Direction, Water Quality, Recharge Sources, and Age, Great Sand Dunes National Monument, South-Central Colorado, 2000-2001 US Geological Survey, Michael G. Rupert and L. Niel Plummer Hydrogeology of the San Luis Valley, Colorado, An Overview—and a Look at the Future (.pdf file, 44 kb) Philip A. Emery San Luis Valley Project, Closed Basin Division, Colorado (.pdf file, 1.21 mb) Alamosa Field Divsion Staff, Bureau of Reclamation The Role of Streams in the Development of the Great Sand Dunes and their Connection with the Hydrologic Cycle (.pdf, 5.7 mb) Andrew D. Valdez, Great Sand Dunes Geologist |

Last updated: March 5, 2024