Public Domain |

Searching for Wealth Beyond the SunsetMotivated by “God, Gold and Glory” Spain sent a series of military expeditions to explore the Great Plains beginning in 1541. Converting Indians would bring glory to the converter in an age that related everything to religion, but the real draw was finding wealth in the fantastic, mythical kingdoms that always seemed to lie to the west, just beyond the currently explored territory. Opening a Future Trade RouteBecause they followed the Arkansas River, many of these expeditions came through this area of Kansas. These journeys pioneered the route that William Becknell would later use in 1821 to open up the Santa Fe Trade. They started out from the area now known as New Mexico and by 1821, the year Becknell opened the Santa Fe Trail, there was hardly a place on the Great Plains that had not been explored by the Spanish. |

|

1541 to 1634 - Early Explorations |

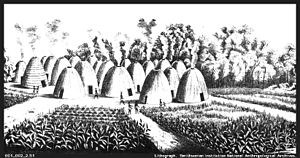

Public Domain 1541 - Vasquez de CoronadoCoronado set out from the area of New Mexico with 350 soldiers. Inspired by the stories of an Indian named the Turk, he was searching for the Seven Cities of Cibola, a legendary place of amazing wealth. After marching about 650 miles without finding anything, Coronado realized the Turk had misled them. He sent back all but 30 of his men and used Texas Indians as guides from that point on. They would eventually reach a village of grass covered huts near Lyons, Kansas, which Coronado named Quivira. Most of the route Coronado used on his return to New Mexico would later become the Santa Fe Trail. 1595 - Francisco Leyva de Bonilla & Antonio GuitiérrezLeyva and Guitiérrez led an unauthorized expedition looking to make a name for themselves and possibly become governors of new Spanish provinces in New Mexico. Their journey took them near present-day Wichita, Kansas before tragedy struck the group. The two leaders fought with each, and eventually Guitiérrez murdered Leyva. Shortly after that the remaining soldiers were attacked by Plains Indians who killed everyone but one Indian servant. |

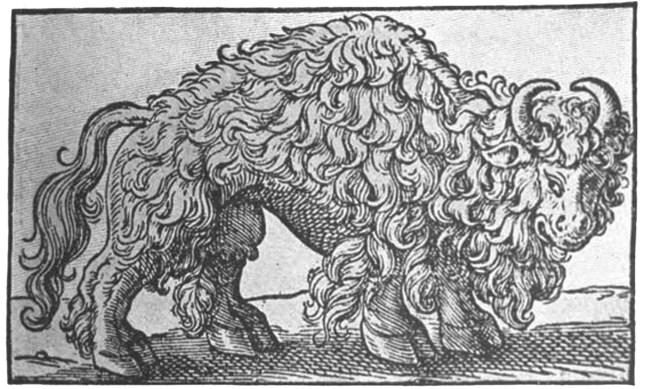

1601 - Juan de OñateBy 1595, Leyva and Guitiérrez’s expedition, along with others, finally prompted the viceroy in Mexico City to authorize Juan de Oñate to start a settlement in New Mexico. Oñate would eventually set out in 1598, leading 129 soldiers and their families, 83 wagons and 700 head of livestock. 1634 Alonso BacaBaca, along with “some men” left Santa Fe and traveled as far as Quivira, mostly using the route of the future Santa Fe Trail. Hostile Indians forced him to return but not before reaching a large river that some people believe was the Mississippi. |

1720 to 1806 - Trade and Diplomatic Missions |

1720 - Pedro de VillasurDuring the 1700s the Spainish were increasingly threatened by foreign competitors in North America. Stories reached them about other white men on the plains and it soon became apparent that the French were moving in on their territory. By 1700 the French were settling into the area of Illinois and the Mississippi River Valley, as well as along the Missouri River. |

1792 - Pedro VialFor the next 60 years the Spanish put their explorations on hold while they fought the Comanche. After establishing peace with them, they looked beyond New Mexico, this time in search of trading opportunities with their neighbors. France had handed Louisiana over to Spain in 1763 and Governor Fernando de la Concha decided it was time to open trade relations with the new Mexican province. 1806 - Facundo MelgaresIn 1800, Spain gave Louisiana back to the French, but immediatley France turned around and sold the territory to the U.S. in 1803. By 1805, Americans began arriving in Santa Fe and in the following year Zebulon Pike led an expedition to the San Luis Valley in New Mexico mostly following the route of the Santa Fe Trail. He arrived in the valley in January of 1807, where New Mexican soldiers briefly detained him for trespassing. |

Last updated: January 30, 2020