Last updated: September 19, 2023

Article

The Rosenwald Schools: Progressive Era Philanthropy in the Segregated South (Teaching with Historic Places)

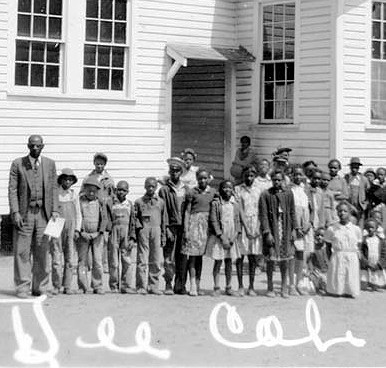

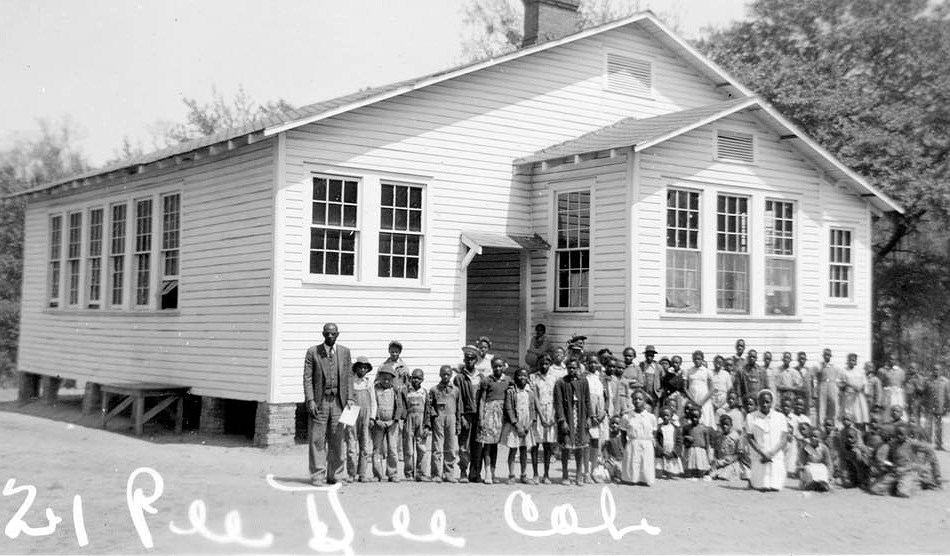

(Rosenwald School students; S.C. Department of Archives & History)

The Pledge of Allegiance. The National Anthem. The teacher tells a story.

A school day in a Rosenwald School in the early 20th century was in many ways similar to school days today. But before they could start their day, this class of African American students in the segregated south walked to school. When they arrived, they had to sweep out the classroom, collect wood for the stove, and draw water from a well. The students were proud of their schoolhouse. Before it was built, some had attended classes in living rooms or front yards. Some had learned to read while sitting in a field or in church pews. But that was before their community built them a real school by donating labor, materials, and money to match a grant from the Rosenwald school building program.

The Rosenwald school building program was a Progressive Era program funded by philanthropist Julius Rosenwald. He partnered with African American educator and activist Booker T. Washington, first working with Washington's Tuskegee Institute and then forming an independent foundation to manage the school program. After meeting in 1912, the two men built thousands of schools for black students in 15 states. The Rosenwald Schools, as they are known, were often the first schools in a black community and helped improve education across the South.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Covers "The Rosenwald School Building Fund and Associated Buildings (Alabama)," "Rosenwald Schools of Anne Arundel County, Maryland (1921-1932)," "The Rosenwald School Building Program in South Carolina, 1917-1932," "The Rosenwald School Building Program in Texas, 1920-1932,"

and "Rosenwald Schools in Virginia." It was published in June 2015. This lesson was written by Rebekah Dobrasko, historian with the Texas Department of Transportation, previously with the South Carolina State Historic Preservation Office. It was edited by Teaching with Historic Places staff. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in units on the history of education in the United States, the Progressive Era, African American history, and early 20th century school architecture.

Time Period: Early-20th century

Relevant United States History

Standards for Grades 5-12

The Rosenwald Schools: Progressive Era Philanthropy in the Segregated South

relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

-

Standard 1A: The student understands the origin of the Progressives and the coalitions they formed to deal with issues at the local and state levels.

-

Standard 1C: The student understands the limitations of Progressivism and the alternatives offered by various groups.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

The Rosenwald Schools: Progressive Era Philanthropy in the Segregated South

relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

-

Standard A - The student compares similarities and differences in the ways groups, societies, and cultures meet human needs and concerns.

Theme II: Time, Continuity, and Change.

-

Standard B - The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns of historical change and continuity.

-

Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

-

Standard E - The student develops critical sensitivities such as empathy and skepticism regarding attitudes, values, and behaviors of people in different historical contexts.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environments.

-

Standard D - The student estimates distance, calculates scale, and distinguishes other geographic relationships such as population density and spatial distribution patterns.

-

Standard G - The student describes how people create places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

-

Standard H - The student examines, interprets, and analyzes physical and cultural patterns and their interactions, such as land uses, settlement patterns, cultural transmission of customs and ideas, and ecosystem changes.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity.

-

Standard B - The student describes personal connections to place--associated with community, nation, and world.

-

Standard G - The student identifies and interprets examples of stereotyping, conformity, and altruism.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions.

-

Standard G - The student applies knowledge of how groups and institutions work to meet individual needs and promote the common good.

Theme VII: Production, Distribution, and Consumption.

-

Standard C - The student explains the difference between private and public goods and services.

-

Standard F - The student explains and illustrates how values and beliefs influence different economic decisions.

Objectives

1. To describe the Progressive Era forces behind the modernization of schools for African American students in the segregated South;

2. To identify Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington as founders of the Rosenwald school building program;

3. To describe the architectural features of Rosenwald schools and how the schools were used;

4. To report on a Progressive Era leader and explain his or her motivations and accomplishments.

Materials for students

The materials listed below can either be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students.

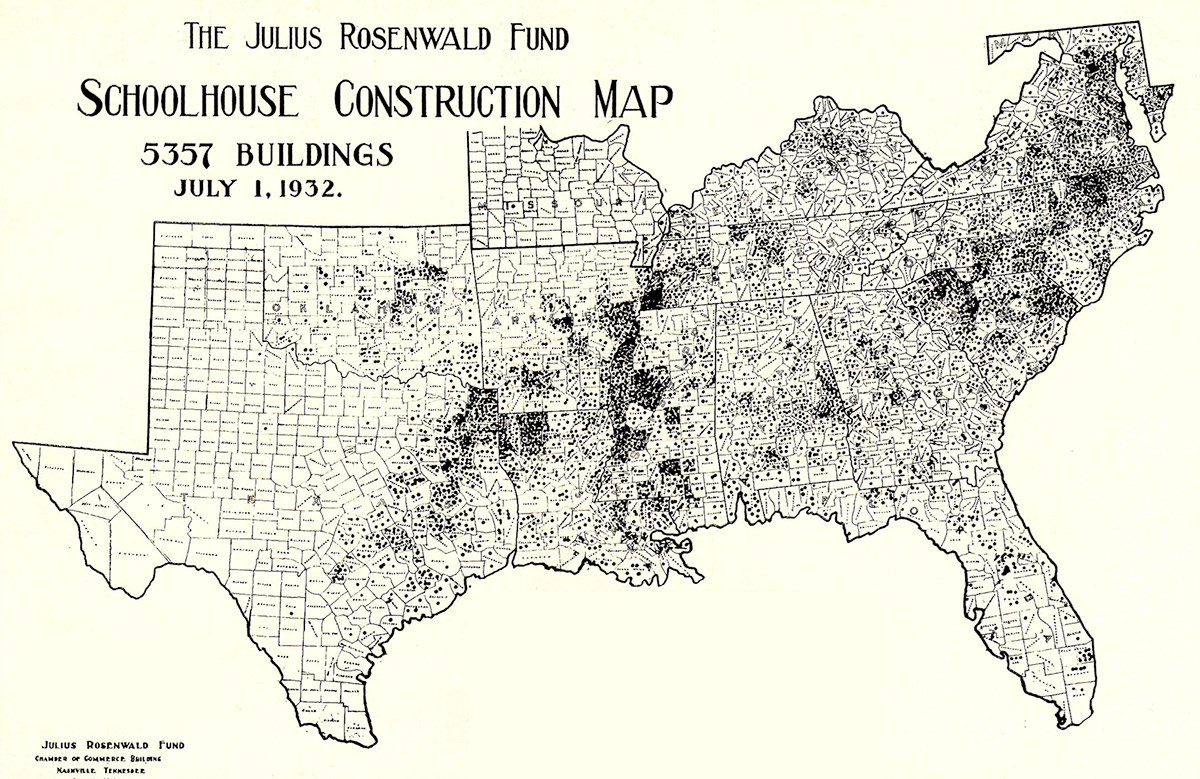

1. One historic map produced by the Julius Rosenwald Fund in 1932 showing the locations of Rosenwald schools across the South;

2. Three readings on the beginnings of the Rosenwald school building program, Rosenwald architecture, and the fate of Rosenwald schools and the program;

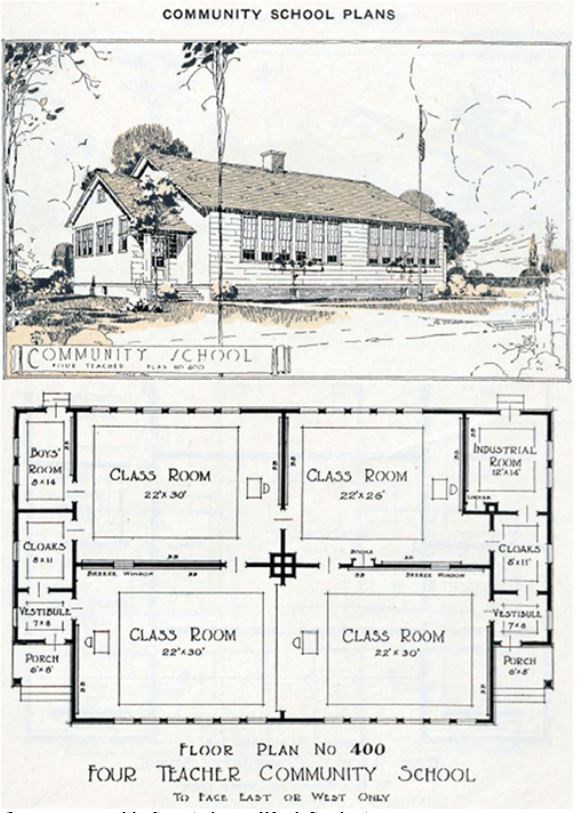

3. Three historic photographs of Rosenwald schools and a building plan for a four-teacher Rosenwald School.

Visiting the sites

Rosenwald schools were constructed in fifteen Southern states. Many schools are no longer extant, while other schools are abandoned or repurposed into other uses. The State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) for each state is a good place to start to find a Rosenwald school for the students to visit. Many states have a website or a list to identify Rosenwald schools by state.

The Pine Grove Rosenwald School that appears in this lesson is located at 937 Piney Woods Road, Columbia, South Carolina. The community center is administered by the Richland County Recreation Commission and is also available for rentals. For additional information call 803-213-1296.

The Carroll School in York County, South Carolina, is located at 4789 Mobley Store Rd., Rock Hill, SC. The school building offers a special program, the Rosenwald 5th Grade Field Study at the Carroll School, for local students to learn about the Great Depression and education at Rosenwald schools.

The Columbia Rosenwald School is located at 247 E. Brazos Avenue, West Columbia, Texas. It is open to the public as part of the Columbia Historical Museum. For additional information call 979-345-6125 or 979-345-3123.

The Scrabble School is located at 111 Scrabble Road, Castleton, Virginia, east of Sperryville Pike between Culpepper and Luray, Virginia. It is open to the public by appointment. For additional information call 540-222-1457.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

What kind of building do you think this is? What makes you think so?

Setting the Stage

In the 19th century, before emancipation, it was illegal for enslaved people in the United States to learn how to read or to go to school. Many white Americans were afraid that education would lead to rebellion. After the Civil War, freed African Americans wanted to take advantage of the opportunities to learn skills like reading, writing, and arithmetic. They knew that these skills were important to economic freedom, exercising citizenship, and getting a job.

During Reconstruction, many Southern states began to give some money for public education and southern public schools were available to both races. Blacks and whites attended public schools together. However, the South’s economy had been devastated by the war and disrupted by emancipation. Even when the U.S. government tried to support education in the South, there was little money available. At the end of Reconstruction, as white Democrats took over government from the Republicans, schools became racially segregated. Of the little funding that existed, most money went to white schools and black students had fewer school buildings, books, and teachers, on average.1

Access to public education was poor across the South, and African American communities bore the brunt of it. In 1909, in Lowndes County, Alabama, white schools received $20 per student while black schools only received $0.67 per student. North Carolina’s Edgecombe County paid for janitors, electricity, water, and transportation at white schools, while none of those services went to black schools. Many African American students attended school in churches, private homes, and fields because they had no schools.2 The same inequalities could be found in other states with segregated education.

Many private organizations such as missionary groups, churches, and other philanthropic groups founded schools for African Americans in an effort to address the funding gap in segregated education. One such well-known school was Tuskegee Institute in rural Tuskegee, Alabama. Opened in 1881 as a “normal” school, or school for teachers, Tuskegee’s board of directors hired Booker T. Washington to lead the school. Washington was born a slave, and had become involved in the politics of education. Washington’s partnership with white northern businessman Julius Rosenwald led to a collaboration that improved African American education across the South.

1 Walter Edgar, South Carolina: A History (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998).

2 The Rosenwald School Building Fund in Alabama (1913-1932) MPS; Edgar, 463-464; Marvin A. Brown, "Rosenwald Schools in Edgecombe, Halifax, Johnston, Nash, Wayne, and Wilson Counties, North Carolina," report prepared for North Carolina Department of Transportation, 2007, available online.

Public schools in the South were racially segregated in the early 20th century. The school boards generally gave more money to support white schools than black schools. The Rosenwald school building program gave African American communities funding to build and supply schools for black students between 1913 and 1932.

Each dot on the map represents one Rosenwald School.

Questions for Map 1

1) What states appear on the map? What shared history do they have?.

2) Pick out any state on the map. Do you see any patterns to the schools constructed in that state? What might account for these patterns?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: The Progressive Era and the Rosenwald School Building Program

At the beginning of the 20th century, the United States was moving from a mostly agrarian society to an industrial one. Factories were not pleasant places to work: they paid very little, workers had long hours, and smoke and pollution made people sick. The workers’ housing was cramped and people lived too close together in cities, which helped spread disease. Some middle and upper class people noticed these problems and wanted to do something about them. They created organizations and citizen groups to solve social problems like long work hours, child labor, unsafe living conditions, and alcoholism. They fought for women’s right to vote. Others built schools and libraries. This time period became known as the Progressive Era and these people are known as the Progressives.

Many Progressives thought education was the best way to help improve poorer peoples’ lives. They promoted a “practical” education to teach skills like farming, carpentry, and housekeeping. In the South, schools were segregated by law and the white schools got more funding than black schools. This meant white students usually had better books, more teachers, and more comfortable school buildings than black students. Some white Progressives saw that education for black students needed to improve and some decided to work with African Americans to do something about the problem.

Booker T. Washington was a well-known African American educator and Progressive Era reformer who helped found the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Washington was born around 1856 as a slave in Virginia. After the Civil War, he went to a rural grade school opened by the Union Army. The Union Army ran several grade schools in the South to teach freed African Americans. Washington believed that education could help people escape poverty. He wanted to help poor African Americans in the South, so he became a teacher and trained other African Americans to be teachers. Washington moved to Alabama in 1881 to help found a new school for teachers. The school was called the Tuskegee Institute. As its president, Washington raised money for Tuskegee and for other black schools in Alabama.1

Julius Rosenwald was a white Progressive who lived in Chicago, Illinois. In the early 1900s, Rosenwald was the president of Sears, Roebuck and Company department store and very wealthy. Rosenwald used his money to fund Progressive Era projects and causes. One of these causes was Southern education. Rosenwald met Washington in Chicago in 1911 at a fundraiser and the two men discovered that they had similar goals. Washington asked Rosenwald to serve on the Board of Directors of Tuskegee. Rosenwald agreed.

In 1912, Rosenwald gave a small grant to the Tuskegee Institute so it could build six African American schools. Washington used the funds to build these rural schools in Alabama. The first Rosenwald grants allowed black students to move into buildings designed to be schools. They no longer had to attend school in a church or a field. This was the start of the Rosenwald school building program.

Rosenwald donated more money for building schools in Alabama in 1914. He gave $30,000 for one hundred schools. Other states heard about Rosenwald and they applied for money to build schools. Rosenwald agreed to give more funds in 1916 and built 200 schools outside of Alabama. He did this with Washington’s and the Tuskegee Institute’s support. When Washington died in 1915, Rosenwald chose to manage the Fund without Tuskegee and turn it into an independent foundation.2

Julius Rosenwald created the Rosenwald Fund in 1917 to manage his growing school building program. The fund moved to Nashville, Tennessee in 1920 when it grew too large for Tuskegee to manage it. The new Rosenwald Fund employees at the Nashville office set new standards for schools. The grants now required matching funds from the communities that wanted schools. The local African American community and its white school district had to match the amount of the grant. Rosenwald asked for a match to encourage communities to work together in building the schools. Some community members contributed building materials and labor as their match. Black communities also held fish frys, bake sales, and other events to raise money. Rosenwald hoped his money would jumpstart a school and then not need his support.

The Rosenwald school building program told the communities how to build the schools. It sent detailed building plans out with the matching grants. These plans described building materials, landscaping, and even paint colors. The Tuskegee Institute hired black architects to design the first schools. When the Fund moved to Nashville, it hired white architect Fletcher Dresslar to design new school building plans. The Rosenwald program was most active between 1920 and 1928. During those years, it spent over $350,000 a year and built thousands of schools. Most of those schools were built according to Dresslar’s plans.

Julius Rosenwald continued the Fund long after Booker T. Washington’s death in 1915, but his gifts waned by the early 1930s. Rosenwald began to limit his gifts to the Fund after the stock market crashed in 1928 and he died in 1932. That year marked the end of grants for schools. Rosenwald died hoping that Southern states would continue building black schools by his example, but they did not. The Fund continued to give small amounts money for other projects like public health and school instruction until it closed for good in the 1940s.

Questions for Reading 1

1) What was the Progressive Movement? Who were the Progressives?

2) Who were Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington? How did each contribute to African American education?

3) Why did the Rosenwald program require a match to its grants? Do you think this was a good idea? Why or why not?

4) How does education improve someone's life? How do you think it improved the lives of the students who went to Rosenwald schools?

Reading 1 was compiled from Mary S. Hoffschwelle, The Rosenwald Schools of the American South (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2006); Jeff Mansell and Alabama Historical Commission staff, The Rosenwald School Building Fund and Associated Buildings (Alabama), National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1997); Karen D. Riles, The Rosenwald School Building Program in Texas, 1920-1932, National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form, (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1998); Lindsay C. M. Weathers, The Rosenwald School Building Program in South Carolina, 1917-1932, National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form, (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2008).

1 Washington’s background is condensed from Stephanie Deutsch, You Need A Schoolhouse: Booker T. Washington, Julius Rosenwald, and the Building of Schools for the Segregated South. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2011.

2 National Trust for Historic Preservation. "History of the Rosenwald School Program."

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Building Practical Schools with the Rosenwald Program

The Rosenwald school building program sent detailed instructions to the communities that won grant money. The Progressives promoted clean and healthy environments. Rosenwald schools were supposed to be large, comfortable spaces with fresh air and good light. Architects at Tuskegee Institute’s architectural program designed the first Rosenwald schools. Three types of school building plans were available in 1915. The plans included a school designed for one teacher, a larger central/county school, and a county training school.

The Rosenwald Fund only granted money to communities that followed its instructions. The instructions included written descriptions of what the schools should look like and architectural plans. Architectural plans are drawings and measurements used by builders to construct buildings. The Rosenwald program had the following types of plans:

-

Elevation plan shows the side of a building as it would appear to a person standing in front of the building.

-

Oblique elevation shows two sides of the building as it would appear to a person standing at the corner of the building.

-

Floor plans show the porches, stairs, rooms, walls, fireplaces/stoves, and doors inside the building. Floor plans show the building’s layout as it would appear if a person was above the building looking down.

-

Site plans show the location of the building and its surroundings, which may include wells, privies, landscaping, or roads. Site plans are like maps of a property.

When the new Rosenwald Fund moved from Tuskegee to Nashville, it hired architect Fletcher Dresslar to revise the architectural plans for Rosenwald schools. Dresslar’s new plans provided better lighting and air flow in the classrooms. Dresslar put the school east-west on the land and described the types of window shades to install. He designed one-story schools because they were cheap and easy to build. The Rosenwald Fund had school plans for one teacher up to seven teachers. The plans also recommended the school site’s size, paint colors, and landscaping.

Thousands of small communities used the program’s instructions to plan their schools. Therefore, most of the schools looked very similar. The schools were one story and raised off the ground on brick piers. Most of the schools were built of wood and had wood siding. A few larger schools were brick. The schools all had brick chimneys. A typical feature of the Rosenwald schools is large windows placed very close together. Each classroom had very tall windows that almost covered the inside wall. The windows were wood with panes of glass and opened to allow fresh air into the school. They were lined up close together to let in a lot of light without casting thick shadows. The site plans for Rosenwald schools required the buildings be lined up to the cardinal directions (east-west-north-south) to align with the movement of the sun.

The Rosenwald program also dictated paint colors for the buildings. The architects chose light paint colors that would help reflect sunshine in the classroom. Very few Rosenwald schools had electricity because of their rural location. Students and teachers relied on the sun for light. Rosenwald schools had gray or beige walls. Ceilings were light cream or ivory. Paint on the outside of the school was either brown with white trim around the windows and doors or white with gray trim. The Fund told communities that this paint would increase the amount of light in the classroom, add beauty to the interior, and increase the durability of the building.

The Rosenwald Fund did not just give money for school houses. Communities could ask for a grant to build a teacher’s home, known as a “teacherage.” These homes provided housing for black school teachers. Only African American teachers could teach at Rosenwald schools because of segregation. These teachers came from black colleges in the South, like the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Most teachers were not from the rural areas where Rosenwald schools were located, so they needed a place to live while they taught. Teacherages provided housing for three to five teachers and the house was often adjacent to a Rosenwald school. The Fund built 217 teacherages across the South.

Other Rosenwald buildings included shop buildings, where students practiced carpentry, metal smithing, and other industrial activities. The Tuskegee Institute, Booker T. Washington, and other Progressives believed a practical education was the best way to decrease poverty. These buildings used similar materials to the schools, such as wood siding and large windows. Finally, there were no inside restrooms in Rosenwald schools. The Fund instructed communities to build outdoor water wells and privies or outhouses.

Questions for Reading 2

1) Along with schoolhouses, what other kinds of buildings did the Rosenwald Fund sponsor? Why?

2) What problems did the school designers try to solve with their designs? How did the design of Rosenwald schools help the students and teachers?

3) If someone asked you to build a Rosenwald School, which of the four types of building plans described in the reading do you think would be the most helpful? Why?

4) In what ways do you think two Rosenwald school properties could be similar? How might they be different?

Reading 2 was compiled from Mary S. Hoffschwelle, Preserving Rosenwald Schools, (Washington, DC: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 2012); Jeff Mansell and Alabama Historical Commission staff, The Rosenwald School Building Fund and Associated Buildings (Alabama), National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1997); Karen D. Riles, The Rosenwald School Building Program in Texas, 1920-1932, National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form, (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1998); Lindsay C. M. Weathers, The Rosenwald School Building Program in South Carolina, 1917-1932, National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form, (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2008).

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Rosenwald Schools, Then and Now

A Rosenwald school was often the first school building for African American students in a Southern community. Building a Rosenwald school allowed students and teachers to move out of churches, barns, or fields. A few larger schools had auditoriums that were used by both students and by the community. The Rosenwald Fund granted funds to support education in general and the Rosenwald schools were more than schoolhouses. They became centers for communities to gather and gave people hope for a better future.

The Rosenwald Fund did more than help build schools, teacherages, and outbuildings. For example, the Fund required school districts to have a minimum school term. It provided a grant for teachers’ pay to keep them working longer. That gave students more time in the classroom each year. African American teachers were paid more to teach at Rosenwald schools than at other schools for black students, too. The Fund also provided a collection of new books to each school that applied for a library between 1927 and 1931. By 1929, the fund offered buses for transportation. This was necessary because local school boards often refused to give new schools funding for a bus. The Fund granted some schools a radio. Others received a portrait of Julius Rosenwald to hang on the classroom wall.

The Fund sponsored the first “Rosenwald School Day” in 1927. The students and teachers were always responsible for cleaning their school and grounds, but on this day their community gathered to help. They painted the buildings, cleaned the yards, and listened to the students present songs and speeches. The communities also invited their state school agents on that day. They learned more ways to improve education and had a chance to report to the agent on children’s accomplishments. The Rosenwald School Day was a yearly event at Rosenwald schools in the 1930s with or without the Fund’s grants.

The Wall Street Stock Market crashed in 1929 and the stock value of Rosenwald’s company, Sears, Roebuck and Co., fell. The Fund’s interest in building schools was sinking, too. It wanted to fund other Progressive causes, like health education and teacher training. By 1930, the Rosenwald Fund slowed its grants for new schools. The Fund could not afford to match as many grants as it once did. Julius Rosenwald worried from the start of the program that local school districts would become dependent on the grants. He believed that districts and states should give more funds to black schools instead of relying on private benefactors to educate its citizens. Unfortunately, the school districts were often controlled by people who did not want to give more funding to support black schools.

The Rosenwald school building program ended in 1932 when Julius Rosenwald died. However, the Fund lived on and continued to sponsor Progressive projects in the 1930s and 1940s. Eleanor Roosevelt, first lady and a Progressive, served on the board of trustees between 1940 until the Fund closed for good in 1948. Many of the schools stayed open for another 20 years.

The Rosenwald school building program had a widespread impact on black education in the South and its effects were felt for decades. When it ended, the Fund had helped build over 5,000 new schoolhouses, teachers’ homes, and industrial training workshops. It spent millions of dollars in fifteen states. Over 600,000 students went to Rosenwald schools from the 1910s until the 1960s. Many Rosenwald schools closed when the states desegregated public schools in the 1950s and 1960s. Some school districts tore down the buildings after they closed. Some schoolhouses were used as community centers, homes, and sheds for storage. Most Rosenwald schools were abandoned and left to fall apart.

In the 21st century, the historic Rosenwald schools are being saved by the historic preservation movement. Historic preservation means to save and maintain old buildings. Preservationists work to make sure historic buildings and places survive. One reason people preserve old buildings is because they provide information about the past. Historic places reveal the values, needs, and hopes of the people who designed them and the people who used them. Historic preservation at Rosenwald schools involves finding modern grant funds to repair these buildings. Preservation also involves researching and writing the history of these schools, interviewing people who attended the schools, and finding new uses for the old Rosenwald buildings. The National Trust for Historic Preservation considers Rosenwald Schools to be a “National Treasure.”

While Rosenwald schools are no longer schoolhouses, some are used for education. Students can go on a history field trip to the Carroll School in York County, SC. Other historic Rosenwald school buildings are museums, like the Columbia Rosenwald School in West Columbia, TX. Some school buildings, like the Scrabble School in Virginia, are senior centers or community centers. Important places like the Rosenwald Schools can be reused for many purposes. Preserving a Rosenwald school preserves more than a building: it preserves a community’s heritage and evidence of its history.

Questions for Reading 3

1) What did the Rosenwald school building program do to improve education for black students in the South? List some of the ways it helped.

2) Why did the Rosenwald Fund end? Do you think it was successful? Why or why not?

3) What happened in the 1960s that made the Rosenwald Schools close? Where do you think the students went?

4) What historic buildings are in your community? How do they serve the community today?

Reading 3 was compiled from from Mary S. Hoffschwelle, “Preserving Rosenwald Schools,” (Washington, DC: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 2012); Jeff Mansell and Alabama Historical Commission staff, The Rosenwald School Building Fund and Associated Buildings (Alabama), National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1997); Hoffschwelle, Mary S., “Preserving Rosenwald Schools,” (Washington, DC: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 2012); and Karen D. Riles, The Rosenwald School Building Program in Texas, 1920-1932, National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form, (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1998).

Visual Evidence

Drawing 1: Community School Plans, Bulletin No. 3, the Julius Rosenwald Fund. 1924.

Questions for Drawing 1

1) What two types of architectural plans are shown in this photograph? What does each one reveal about the building? (Refer to Reading 2 if necessary)

2) In what ways is the school in this architectural plan similar to your school building? How is it different? Why do you think they are different?

3) How is attending school in a building like this different from attending school in a church or someone's home? What are the benefits of a school building?

Visual Evidence

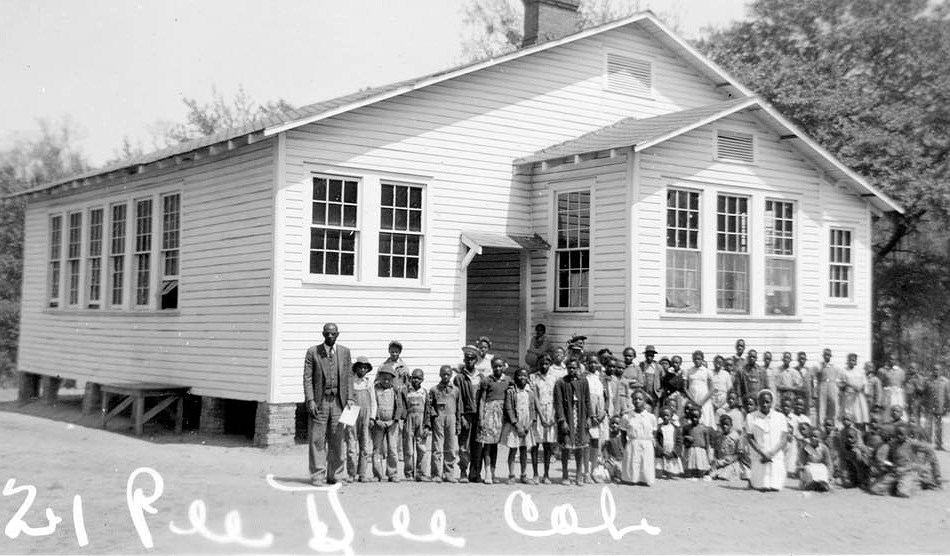

Photo 1: Pee Dee Rosenwald School, Marion County, South Carolina, c. 1935.

Pee Dee Rosenwald School was built in 1922-1923 with two classrooms and two cloakrooms. A chalkboard was located on the partition between the two rooms. Students' desks faced the chalkboard with the teachers' desks located off to the side. The wall between the classrooms could be moved to open a large space in the school.

Questions for Photo 1

1) Compare the photo of this school with the descriptions of Rosenwald schools in the Readings. What evidence in the photograph tells you that this is a Rosenwald School? List all of the characteristic features of Rosenwald schools you can find.

2) In what ways is this school similar to yours? How is it different? Give examples from the photograph and the caption.

3) Compare the Pee Dee School to the building drawn in the architectural plan in Drawing 1. How are the two buildings similar? How are they different?

Visual Evidence

Photo 2: Interior, Pine Grove Rosenwald School, Columbia, South Carolina, c. 1936.

Rosenwald schools can be community centers for residents of all ages and the Pine Grove School has served its community for over 80 years. Pine Grove School opened in 1923 and closed in 1950. In 1968, the school district sold the building to the Pine Grove Community Development Center. The building reopened as a community center. In the 21st century, family reunions, community meetings, and church events are still held at the historic school.

Questions for Photo 2

1) Who is using the Pine Grove School in Photo 2? Why do you think they are there? How can you tell?

2) How are the people in the photo controlling the air temperature? How are they controlling the light in the room? What other features in the room make it a pleasant space?

3) What evidence of the Progressive Era can you find in this photograph? (Refer to Readings 1-3 if necessary)

4) How has the use of the school changed over time? How has it stayed the same?

Visual Evidence

Photo 3: Spann Rosenwald School, Madison County, Tennessee, 1939.

(Photograph courtesy of Tennessee State Library and Archives)

The Spann Rosenwald School was built in 1926 on two acres of land that included a schoolhouse, outbuilding, and garden. The school had two teachers and seventy-one students.

Questions for Photo 3

1) In what type of area do you think this school was built? How can you tell?

2) How do you think students used the school yard? How might the community have used it? Why do you think so?

3) How is this school similar to the school buildings in Drawing 1 and Photo 1? How is it different?

4) What man-made features of the landscape might be part of the Fund's recommendations? Why do you think so? (Refer to Reading 2 if necessary)

Putting It All Together

The following activities will help students better understand the Progressive movement, how it affected education and other aspects of American life, and how the architecture of Rosenwald schools reflected the educational philosophies of the Fund's founders.

Activity 1: Rosenwald Schools, Yesterday and Today

Have each student research Rosenwald schools in the Fisk University Rosenwald School database. Each student will pick a state and county and make a list of all the Rosenwald schools built in that county. Ask each student to find a county highway map for that county and map the locations of the Rosenwald schools. They may use historic county highway maps, school district information, or online information from historical societies, libraries, and other sources to find the locations of these schools. Ask your students: Do any of the schools survive today? Why or why not? If any exist, what are they used for today?

Then, have each student create a poster to exhibit information about their chosen region's Rosenwald schools. Each exhibit should include one or more map, photographs of the schools, historical information about the region and the schools, and other information of interest.

For students whose communities have schools that still exist and are open to the public, they may prepare a travel brochure for that school instead of an exhibit. Information in the brochure should include: a description of the Rosenwald school building program, the name of the Rosenwald school, the location, a map/directions to the property, name of the owner, current use of the building, a short history of the school, and photographs if available.

Activity 2: Research Progressive Era Leaders

The Progressive Era was a period in American history during the late 19th-to-early-20th century. It was characterized by social and political activism and reform. The spirit of reform emerged largely as a reaction to increased industrialism and urbanization and growing concern about political corruption; working conditions; urban slums; and dramatic economic, social, and political disparities, locally and nationally. Education was only one of numerous causes tackled by reformers.

Have students select one of the following individuals influential in the American Progressive Era.

|

Jane Addams |

William and Charles Mayo |

Andrew Carnegie |

|

John Dewey |

W.E.B. DuBois |

Henry Ford |

|

Louis Hine |

Charles Evan Hughes |

Anna Jeanes |

|

Hiram Johnson |

Mary Harris "Mother" Jones |

Florence Kelley |

|

Louis Brandeis |

Robert LaFollette |

Alice Paul |

|

Gifford Pinchot |

Fayette Avery McKenzie |

Jacob Riis |

|

Ida B. Wells |

John D. Rockefeller |

Upton Sinclair |

|

John Slater |

Theodore Roosevelt |

Ida Tarbell |

Each student will design a poster about this person, which will include biographical information, a picture of the person, and an explanation of that person's key contributions to the Progressive movement.

Display the posters on the classroom wall; divide the class in half and have each half take turns 1) viewing the posters and asking questions and 2) standing with their poster and answering questions. Conclude with a whole class discussion comparing and contrasting the goals, methods, and accomplishments of those the class researched with those of Booker T. Washington and Julius Rosenwald.

Activity 3: Discover History in Your Local Historic Places

Many of the original Rosenwald Schools that survive today are standing because historic preservationists and local communities worked to save them from demolition. Some of these historic school buildings are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, a program of the National Park Service. Have your students work in small groups and use the National Register database to identify a historic building or buildings in their county or region and then investigate the history of that site. You may want to instruct them to find a school building property or one from the Progressive Era.

Have each group design a booklet about the historic building they find in the National Register. The booklet should include short essays about the building's history, including descriptions of what it was used for when it was built, what it is used for today, and why it is an important historic site. They should tie the historic site to the national historic events, people, or movements they have learned about in school. Students should also include images in the booklet. They can use historic photographs if they are available and contemporary photographs.

Have your students draw their own architectural plans of the building, using the information about plans in Reading 2 and the information they find in the National Register nomination file.

Finally, have students offer copies of their booklet to the owner of the historic property, the State Historic Preservation Office, and their local library or historical society.

The Rosenwald Schools: Progressive Era Philanthropy in the Segregated South--

Supplementary Resources

By learning about the Rosenwald Schools and their origins, students are introduced to the issue of historic preservation, the impact of segregated education in the South, the values of the Progressive movement, and how Progressive values are embodied in Rosenwald school architecture. Students, teachers, and others who are interested in learning more about these subjects will find that the Internet offers a variety of materials.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation

The National Trust for Historic Preservation maintains a website on its Rosenwald School Initiative. This website provides in-depth information on the Rosenwald program, examples of school architecture and building plans, and case studies on the preservation of Rosenwald schools across the South.

Fisk University Rosenwald Fund Database

Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee holds the records of the Rosenwald Fund. It has an online database that searches all the schools in its records, and has maps, photographs, correspondence, and other papers related to the funds. This database can be used for some of the activities in the lesson plan.

National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers

Each state has a State Historic Preservation Office to oversee the documentation of historic properties and issues related to historic preservation. Many southern SHPOs have additional information on the Rosenwald schools in their states. Visit the National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers website for a list of all the SHPOs and links to their websites.

HistorySouth.org: Rosenwald Schools

HistorySouth provides educational resources including a detailed bibliography of Julius Rosenwald, information about the Rosenwald Fund, and surviving Rosenwald schools. It is maintained by historian Tom Hanchett, of the Levine Museum of the New South in Charlotte, NC.

Bibliography

A detailed history on Progressive education programs for African Americans can be found in John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss, Jr., From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans, 7th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1994), 264-277.

Tags

- education

- african american history

- education history

- rosenwald schools

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- civil rights

- art and education

- gilded age

- early 20th century

- jewish history

- north carolina

- north carolina history

- south carolina

- south carolina history

- tennessee

- tennessee history

- african american heritage

- civics

- segregated schools

- progressive era

- twhplp

- etc aah

- alabama

- texas