Last updated: May 11, 2023

Article

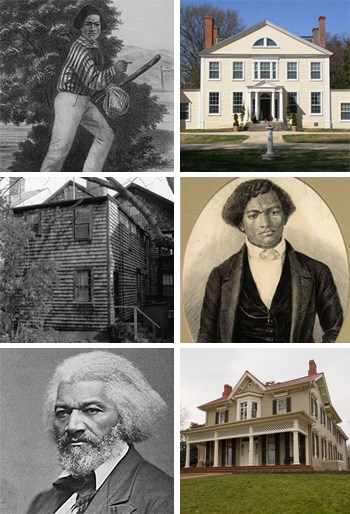

"Journey from Slavery to Statesman": The Homes of Frederick Douglass

Top-left image courtesy of the Library of Congress and top-right image courtesy of Janet Blyberg. Other images courtesy of the National Park Service.

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

Sobbing, the small boy watched his grandmother walk away. Under orders, she had just brought the enslaved child to their master's house at Wye Plantation and left him there. Born ca. 1818 on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, Frederick Douglass never knew who his father was and only saw his mother a few times in his life. Brought up by his grandmother in a small cabin, he gradually realized his enslaved condition; but, he did not live it until his grandmother brought him to the home of his master that day.

Like others, Frederick Douglass yearned for freedom. As a teenager, he made his first escape by canoe, but was caught and returned. He finally escaped in 1838, dressed in a sailor's clothes and using the pass of a free black man. He adopted a new name, married his sweetheart, and began a new life in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Over time, Douglass developed impressive speaking skills, giving stirring and fiery speeches. He became a traveling lecturer both in the U.S. and abroad. Douglass also became a journalist, founding a newspaper, The North Star. Remembering his own flight from slavery, he aided other freedom seekers. He became a leader who advised Abraham Lincoln. Douglass was appointed a United States marshal in 1877 and soon afterward purchased the Cedar Hill estate in Washington, DC. In 1881, he served as the recorder of deeds for the District of Columbia in 1881. He also served as the U.S. minister to Haiti under President Harrison. Douglass remained an advocate of social justice throughout his life, and died a respected statesman at Cedar Hill in 1895. He was the author of many speeches, articles, and three autobiographies.

By examining Douglass's life and three of his homes, students will discover how Douglass grew from an enslaved youth to an empowered and empowering statesman.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration files for Wye House, Nathan and Polly Johnson House (and photographs), and Frederick Douglass National Historic Site (and photographs), as well as other source materials on the life of Frederick Douglass. It was written by Jenny Masur, National Park Service, and edited by the Teaching with Historic Places staff. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in units on the antebellum South, the institution of slavery, and the Underground Railroad.

Time period:1817-1895

Relevant United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

"Journey from Slavery to Statesman": The Homes of Frederick Douglass

relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

-

Standard 2D- The student understands the rapid growth of “the peculiar institution” after 1800 and the varied experiences of African Americans under slavery.

-

Standard 3B- The student understands how the debates over slavery influenced politics and sectionalism.

Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

-

Standard 1A- The student understands how the North and South differed and how politics and ideologies led to the Civil War.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies) "Journey from Slavery to Statesman": The Homes of Frederick Douglass relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

-

Standard B- The student explains how information and experiences may be interpreted by people from diverse cultural perspectives and frames of reference.

-

Standard D- The student explains why individuals and groups respond differently to their physical and social environments and/or changes to them on the basis of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environments

-

Standard G- The student describes how people create places that reflect cultural values and ideas as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

Theme IV: Identity Development and Identity

-

Standard A- The student relates personal changes to cultural, social, and historical contexts.

-

Standard B-The student describes personal connections to place—associated with community, nation, and world.

-

Standard D- The student relates such factors as physical endowment and capabilities, learning, motivation, personality, perception, and behavior to individual development.

-

Standard E- The student identifies and describes ways regional, ethnic, and national cultures influence individuals' daily lives.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard B- The student analyzes group and institutional influences on people, events, and elements of culture.

-

Standard E- The student identifies and describes examples of tensions between belief systems and government policies and laws.

-

Standard F- The student describes the role of institutions in furthering both continuity and change.

Theme VI: Power, Authority, and Governance

-

Standard D- The student describes the ways nations and organizations respond to forces of unity and diversity affecting order and security.

-

Standard F- The student explains conditions, actions, and motivations that contribute to conflict and cooperation within and among nations.

-

Standard H- The student explains and applies concepts such as power, role, status, justice, and influence to the examination of persistent issues and social problems.

Theme VII: Production, Distribution, and Consumption

-

Standard F- The student explains and illustrates how values and beliefs influence different economic decisions.

Theme IX: Global Connections

-

Standard B- The student analyzes examples of conflict, cooperation, and interdependence among groups, societies, and nations.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

-

Standard E- The student explains and analyzes various forms of citizen action that influence public policy decisions.

-

Standard F- The student identifies and explains the roles of formal and informal political actors in influencing and shaping public policy and decision-making.

-

Standard H- The student analyzes the effectiveness of selected public policies and citizen behaviors in realizing the stated ideals of a democratic republican form of government.

Objectives for students

1) To locate Douglass's successive homes and describe his life at each.

2) Using Frederick Douglass's life and homes for reference, to compare and contrast the status of an enslaved person, a prosperous free man, and an American statesman in antebellum America.

3) To explain what the Underground Railroad was and describe some of the risks and obstacles to a successful escape from slavery and adjustments to a new life of freedom.

4) To seek out examples of injustice in their community and to provide possible solutions.

5) To write a short autobiography.

Materials for students

The materials listed below can either be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students.

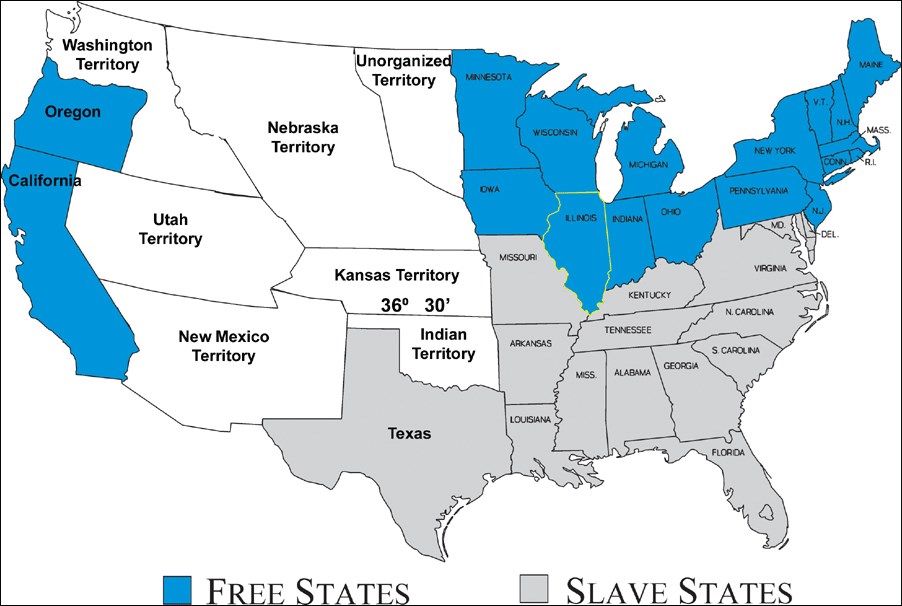

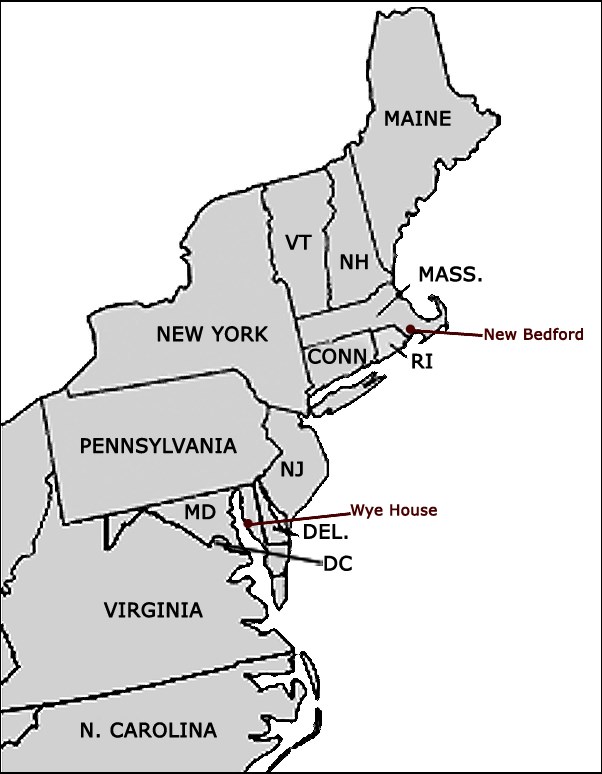

1) two maps of Douglass's homes and the United States in 1860;

2) Four readings to understand Douglass's experiences at each of his homes and how they influenced who he became;

3) three images of Douglass's homes;

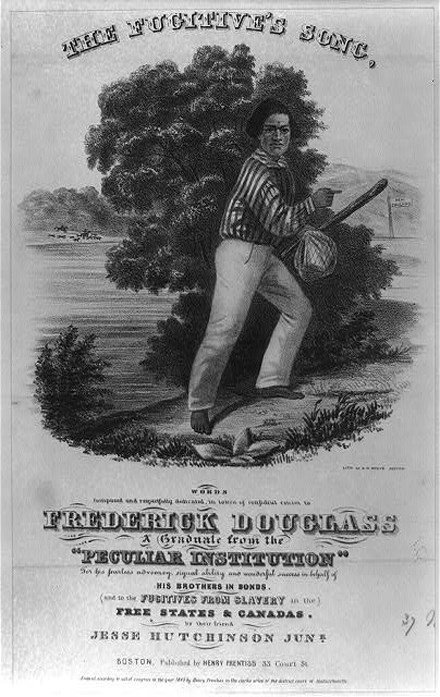

4) one illustration of Frederick Douglass’s escape.

Visiting the site

Wye House is located on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. It is privately owned and not open to the public. The main house, its outbuildings, and surrounding acreage compose a plantation originally established in the 17th century.

The Nathan and Polly Johnson House, owned by a local historical society, is located at 21 Seventh Street, New Bedford, Massachusetts. To get to the house from I-195, take exit 15 to merge onto MA-18 S toward Downtown/New Bedford; continue onto JFK Memorial Highway; turn right onto Union St; and then turn left onto 7th Street, the house will be on the left. The Johnson House is in a section of New Bedford suitable for walking. The New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park, a National Park Service site, has a downloadable walking tour brochure, "The Underground Railroad: New Bedford," which includes the Johnson House. For more information about visiting the house, contact the New Bedford Historical Society at (508) 979-8828 or society@nbhistory.comcastbiz.net. Address written material to: Nathan and Polly Johnson House, P.O. Box 40084, New Bedford, MA 02744.

Cedar Hill is located at 1411 W St. SE, Washington, DC, at the corner of 15th and W Streets. The site is accessible both by public transportation and driving. For more information about access via public transportation, please see the Cedar Hill website. Guests can only tour the site led by a ranger. Reservations are not necessary but all guests must pick up a ticket to join a reserved tour time. Tour times vary but there are usually five tours per day and they last approximately 30 minutes. The house is open every day except for Thanksgiving, December 25th, and January 1st. The park is open approximately from 9a-4:30pm (April-October it is open until 5pm). For more information, call the site at (202) 426-5961 or use the email link on the website. Address written material to: Site Manager; FRDO, 1411 W St. SE, Washington, DC 20020. Any additional information can be found on the park's Web pages.

Setting the Stage

The use of African Americans for enslaved labor began as early as the 16th century in Spanish Florida. Slavery was legal in the United States until the adoption of the 13th Amendment in December of 1865. Throughout the history of slavery in the United States, escape by enslaved men and women, known as "freedom seekers," has been a constant form of resistance. These men and women fled their enslavement not only to obtain freedom, but to avoid the physical and emotional pain inflicted from abuse, separation from families, and the hardship of daily life. Their escapes represented a rejection of their imposed status of enslavement.

In the early 19th century, the economies of the North and South began to go in different directions; the South found slavery more profitable while the North did not. As enslaved labor began to decline in the North, northern states abolished the institution and became a refuge for freedom seekers. Individually or in small groups, a small percentage of those enslaved continued to escape, worrying slaveholders who feared other slaves would follow their example. The Nat Turner Revolt in Virginia (1831) frightened slaveholders who then tightened restrictions on both free and enslaved blacks. On the eve of the Civil War in 1860, southerners continued to enslave about 4,000,000 African Americans.

Determined to attain their freedom, the enslaved escaped however they could. Freedom seekers began going to free settlements in mountains or swamps, or in Spanish Florida, where Native American communities welcomed them. Routes for evading slave catchers included going overland or by water. Disguises and forgeries of travel papers were a part of their strategies. Freedom seekers passed as free, blending into free black populations in large cities. Some even mailed themselves to Philadelphia in boxes or stowed away on ships.

People of conscience aided freedom seekers in need, forming black and white networks and vigilance committees. Biracial cooperation took place with the assistance of various religious groups (to name a few, Quakers, Methodists, Presbyterians, and Unitarians). People who had moral objections to slavery and were politicized by their beliefs became known as abolitionists. Abolitionists were not afraid to use all means of communication to sway public opinion. William Lloyd Garrison started the first abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, in 1831, and antislavery societies organized lectures and petitions. While the abolitionists worked to convince their communities about the evils of slavery, the Fugitive Slave Law Act of 1850 granted southern slaveowners more legal reach into the North. Life was better for freedom seekers in the North but threat of lawful recapture meant they were not entirely free. Some runaways were driven to run to Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, or Europe.

Throughout the 1850s, tension over slavery in the new western territories and states became an increasingly contentious political issue. In 1859, John Brown raided Harper's Ferry to take control of the armory to arm the enslaved to free the South. With this event, the country passed the point of compromise. For the South, Lincoln's election in 1860 proclaimed the North's unwillingness to compromise on the expansion of slavery. Lincoln's opposition to the institution made it clear that he would not support southern arguments. South Carolina became the first state to secede. It led the attack on the United States at Fort Sumter in 1861, starting the Civil War. During the war, Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation enabled African Americans, enslaved and free, to enlist to fight.

Locating the Site

Map 1: Slavery in 1860.

Courtesy Lincoln Home National Historic Site. Information for the creation of Map 3 was obtained from the Abraham Lincoln Historical Digitization website at http://lincoln.lib.niu.edu

Questions for Map 1

1) Those enslaved had to travel from a slave state to a free one to obtain their freedom. Which states were slave states and which were free?

2) Using a classroom map or atlas of the United States, find the Eastern Shore of Maryland, New Bedford, and the District of Columbia. According to Map 1, are they in areas that were free or slave?

3) Which free states were closest for those running to freedom? Which slave states were easiest to escape from? Which were the most difficult? What natural features might you use to aid your escape? (Water routes, mountains, forests, etc.)Locating the Site

Map 2: The Homes of Frederick Douglass.

Original map courtesy of the Lincoln Home National Historic Site

Frederick Douglass was born on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. His master was the captain of the ship that took goods from Wye House plantation to Baltimore. Wye House was the home of the master of the entire Wye Plantation. When Douglass escaped, he headed north from Maryland. When he got as far as New York, antislavery advocates there sent him to New Bedford, Massachusetts, which had a thriving black community with plenty of jobs. Douglass moved a number of times in his life and traveled both within and outside of the U.S. to give antislavery speeches. He made his final home in Washington, DC.

Questions for Map 2

1) Locate Wye House. Wye House was on the Eastern Shore of what body of water that separated the plantation from Baltimore? Why do you think the master would send crops to Baltimore?

2) Locate New Bedford. What very large body of water is New Bedford near? What does that suggest about the city's economy?

3) Locate Washington, DC. How close is it to the Eastern Shore and Baltimore? Why do you think Douglass would have chosen to live in Washington, DC?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Who is Frederick Douglass?

Born into an enslaved life on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in 1818, Frederick Douglass grew up in his grandmother's small cabin. Raised by her, Douglass never knew who his father was and he only saw his mother a few times in his life. While he was still a small boy, his grandmother brought him, under orders, to the master's home at Wye Plantation. This event began Douglass's journey through slavery.

Like other enslaved children, Douglass wore rough clothes and ate slop (leftovers from the kitchen). Unlike other enslaved children, however, he was not restricted to running errands or helping in the fields. Instead, he became the playmate of the plantation owner's son. Despite his access to the plantation house, Douglass was not an equal. He fished and played games the way his white "friend" told him.

He was very intelligent, but never went to school. When he lived in Baltimore working as a house servant, the wife of his temporary master started to teach him to read. When her husband found out, he angrily stopped her. After this, Douglass realized education was a key to success and freedom and he became self-taught.

Sent back to the Eastern Shore, Frederick Douglass yearned for the freedom he saw white men had. He did not want to work in the fields for the rest of his life. As a teenager, Douglass attempted his first escape by canoe from a plantation that had hired Douglass from his owner. He failed and luckily avoided a harsh punishment, but he continued to dream of freedom. Douglass finally escaped in 1838 by boarding a train in Havre de Grace, Maryland, dressed in sailor's clothes and using the pass of a free black man. The following is an excerpt from Douglass's recollection of his escape:

...But I had one friend -- a sailor -- who owned a sailor's protection, which answered somewhat the purpose of free papers -- describing his person and certifying to the fact that he was a free American sailor. The instrument had at its head the American eagle, which at once gave it the appearance of an authorized document. This protection did not, when in my hands, describe its bearer very accurately. Indeed, it called for a man much darker than myself, and close examination of it would have caused my arrest at the start.

…In my clothing I was rigged out in sailor style. I had on a red shirt and a tarpaulin hat and black cravat, tied in sailor fashion…My knowledge of ships and sailor's talk came much to my assistance...1

Terrified that he would be discovered, Douglass described a close call on the train:

I saw on the train several persons who would have known me in any other clothes, and I feared they might recognize me, even in my sailor "rig," and report me to the conductor, who would then subject me to a closer examination, which I knew well would be fatal to me.2

He was not caught. Arriving first in New York City, Douglass continued on to New Bedford, Massachusetts. There he adopted a new name, married his sweetheart (whom he had met in Baltimore), and began a new life. Thanks to the African American married couple who gave Douglass shelter in New Bedford, he realized the privileges and disadvantages (prejudice, threat of recapture) of the life of free blacks in the North. After impressing an audience in Nantucket with his speaking skills, Douglass became a traveling lecturer familiarizing audiences with the realities of slavery. He presented himself so well that he had to publish his autobiography with details of his identity to make his time in slavery believable. After the publication in 1845 of the first of Frederick Douglass's three autobiographies, friends encouraged him to take a trip abroad, in part from fear that the publicity might attract the attention of his former owner. While in Great Britain, Douglass became legally free when he inspired supporters to purchase his freedom. Once back in the United States, Douglass continued to speak out against slavery and began publication of his newspaper, The North Star. Well-known to both free and enslaved people, Douglass remembered his own flight from slavery and aided freedom seekers wherever he lived.

Douglass viewed the Civil War as a war for freedom. When war came, Douglass was the leading African American to advise Abraham Lincoln on the need to end slavery and to urge the use of African American troops. Once Lincoln gave permission for their inclusion, Douglass became a recruiter, beginning with his sons. After the Civil War, Douglass was appointed as the first African American in several government positions -- United States marshal (1887) and recorder of deeds (1881) in Washington, DC. In 1889, President Benjamin Harrison appointed Douglas as the U.S. minister to Haiti. Throughout Douglass's remarkable life, he passionately spoke out against slavery and other social injustices. He died a respected statesman, orator, journalist, and author.

Questions for Reading 1

1) What was Frederick Douglass's life like in slavery? What made his experience different from many others who were enslaved?

2) How did Douglass try to escape the first time? How and when did he successfully escape from Maryland?

3) What did he do once he escaped from slavery? If you had been in his position, do you think you would been so outspoken and risked recognition? Remember, you have a family that will likely suffer if you are caught and you are likely to be punished for escaping. Can you think of a reason why Douglass might not have wanted to publish the details of his escape until after the Civil War?

4) Name a few of Douglass's accomplishments throughout his life. What do you think is the most meaningful?

Reading 1 was compiled from Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (Boston: DeWolfe & Fiske Co., 1892); William McFeely, Frederick Douglass (W.W. Norton & Company; Reprint, 1995); Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (Boston: The Anti-Slavery Office, 1845).

1 Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (Boston: DEWOLFE & FISKE CO., 1892), 246-249.

2 Ibid.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Life at Wye Plantation

Frederick Douglass grew up in Talbot County on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. When he was about seven years old, he left his grandmother's cabin to live more centrally on the plantation near Wye House. There he encountered life under slavery for the first time. The setup of the house and property was different from a small cabin. The owner of Wye House estate had hundreds of bondsmen on various farms. Each farm had an overseer to help run the plantation, but Aaron Anthony, "the overseer of the overseers," was Douglass' master. In his third autobiography, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Douglass described the setting at Wye House plantation, where his master worked for the Lloyd family who owned the plantation:

There was the little red house up the road, occupied by Mr. Seveir, the overseer; a little nearer to my old master's stood a long, low, rough building literally alive with slaves of all ages, sexes, conditions, sizes, and colors. This was called the long quarter. Perched upon a hill east of our house, was a tall dilapidated old brick building, the architectural dimensions of which proclaimed its creation for a different purpose, now occupied by slaves, in a similar manner to the long quarters. Besides these, there were numerous other slave houses and huts, scattered around in the neighborhood, every nook and corner of which, were completely occupied.

Old master's house, a long brick building, plain but substantial, was centrally located, and was an independent establishment. Besides these houses there were barns, stables, store houses, tobacco-houses, blacksmith shops, wheelwright shops, cooper shops; but above all there stood the grandest building my young eyes had ever beheld, called by everyone on the plantation the great house. This was occupied by Col. Lloyd and his family. It was surrounded by numerous and variously shaped out-buildings. There were kitchens, wash-houses, dairies, summer-houses, green-houses, hen-houses, turkey-houses, pigeon-houses, and arbors of many sizes and devices, all neatly painted or whitewashed--interspersed with grand old trees, ornamental and primitive, which afforded delightful shade in summer and imparted to the scene a high degree of stately beauty. The great house itself was a large white wooden building with wings on three sides of it. In front a broad portico (porch) extended the entire length of the building, supported by a long range of columns, which gave to the Colonel's home an air of great dignity and grandeur. It was a treat to my young and gradually opening mind to behold this elaborate exhibition of wealth, power, and beauty.

The carriage entrance to the house was by a large gate, more than a quarter of a mile distant. The intermediate space was a beautiful lawn, very neatly kept and cared for. It was dotted thickly over with trees and flowers. The road or lane from the gate to the great house was richly paved with white pebbles from the beach, and in its course formed a complete circle around the lawn. Not far from the great house were the stately mansions of the dead Lloyds--a place of somber aspect.1

The human environment on the plantation was dominated by slavery. Douglass divided people into three classes: slaves, overseers, and slave owners. All skilled craftsmen were enslaved. Douglass discovered that the slave owner and his representative, the overseer, had the ultimate power. In discussing the environment of the plantation in his autobiography, Douglass wrote:

It was a little nation by itself, having its own language, its own rules, regulations, and customs. The troubles and controversies arising here were not settled by the civil power of the State. The overseer was the important dignitary. He was generally accuser, judge, jury, advocate, and executioner. The criminal was always dumb, and no slave was allowed to testify other than against his brother slave.2

The owner of the estate owned the African Americans who worked for him as property. He was wealthy as a result of their work, and had control over their fate. He decided if they stayed on the estate or were sold elsewhere. He could break up families when selling his "property." Of the owner of the estate, Douglass wrote in his autobiography:

Mr. Lloyd was, at this time, very rich. His slaves alone, numbering as I have said not less than a thousand, were an immense fortune, and though scarcely a month passed without the sale to the Georgia traders, of one or more lots, there was no apparent diminution in the number of his human stock. The selling of any to the State of Georgia was a sore and mournful event to those left behind, as well as to the victims themselves.3

Questions for Reading 2

1) Why was Wye Plantation significant to Douglass? Which buildings were associated with the enslaved African Americans and which were associated with the slaveholders' private and public space?

2) The owner's dwelling and some outbuildings remain today from Douglass's childhood home. What made the main residence a "Great House"? How was it more than just a house? How does it compare to Douglass's master's house? To the overseer's house?

3) Would you be as impressed with the plantation house if you knew it represented your status as a slave?

Reading 2 was adapted and excerpted from Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: From 1817-1882 (London: Christian Age Office, 1882).

1 Frederick Douglass, "A General Survey of the Plantation" in Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: From 1817-1882 (London: Christian Age Office, 1882).

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: New Life in New Bedford

New Bedford was a whaling port, and provided many opportunities for African Americans as seamen and as workers in the shipbuilding industry. The abolitionist leanings of many inhabitants made it friendly to African Americans, especially freedom seekers. Douglass found his arrival there in 1838 significant for a number of reasons. First, for safety's sake, he needed a new name. While enslaved, he was named Frederick Augustus Bailey. Douglass had changed his last name to Johnson when he went to New York City but in New Bedford, there were already a number of people with the same name. Douglass turned to Nathan Johnson, his host in New Bedford, for advice. Frederick's only condition was that he must not change his first name, so that he could "preserve a sense of my identity." Nathan suggested "Douglass" from a character in Sir Walter Scott's poem, "Lady of the Lake."

Secondly, Douglass took note of the differences between the North and the South in the treatment of African Americans. For example, he was impressed by the high standard of living, even for the free blacks and working men:

In the afternoon of the day when I reached New Bedford, I visited the wharves, to take a view of the shipping. Here I found myself surrounded with the strongest proofs of wealth. Lying at the wharves, and riding in the stream, I saw many ships of the finest model, in the best order, and of the largest size . . . . Added to this, almost every body [sic] seemed to be at work, but noiselessly so, compared with what I had been accustomed to in Baltimore. There were no loud songs heard from those engaged in loading and unloading ships. I heard no deep oaths or horrid curses on the laborer. I saw no whipping of men; but all seemed to go smoothly on. Every man appeared to understand his work, and went at it with a sober, yet cheerful earnestness, which betokened the deep interest which he felt in what he was doing, as well as a sense of his own dignity as a man. To me this looked exceedingly strange . . . But the most astonishing as well as the most interesting thing to me was the condition of the colored people, a great many of whom, like myself, had escaped thither as a refuge from the hunters of men. I found many, who had not been seven years out of their chains, living in finer houses, and evidently enjoying more of the comforts of life, than the average of slaveholders in Maryland. I will venture to assert that my friend Mr. Nathan Johnson…lived in a neater house; dined at a better table; took, paid for, and read, more newspapers; better understood the moral, religious, and political character of the nation, -- than nine tenths of the slaveholders in Talbot county, Maryland. Yet Mr. Johnson was a working man. His hands were hardened by toil, and not his alone, but those also of Mrs. Johnson.1

Finally, Douglass found a paying job as a free man:

I found employment, the third day after my arrival, in stowing a sloop with a load of oil. It was new, dirty, and hard work for me; but I went at it with a glad heart and a willing hand. I was now my own master. It was a happy moment, the rapture of which can be understood only by those who have been slaves. It was the first work, the reward of which was to be entirely my own. There was no Master Hugh standing ready, the moment I earned the money, to rob me of it. I worked that day with a pleasure I had never before experienced. I was at work for myself and newly-married wife. It was to me the starting-point of a new existence.2

In New Bedford, Douglass participated in abolitionist meetings and became an anti-slavery lecturer. He traveled extensively, including abroad. Despite his positive experiences in the North, he made it clear that there was always the chance that freedom seekers could be recaptured. Douglass made the following point in a speech in London in 1846:

One word with regard to the fact, that there is no part of America in which a man who has escaped from slavery can be free. This is one of the darkest spots in the American character. I want the audience to remember that there are those who come to this country [Great Britain] who attempt to establish the conviction that slavery belongs entirely to the southern states of America and does not belong to the north. I am here, however, to say that slavery is an American institution-that it belongs to the entire community; that the whole land is one great hunting-ground for catching slaves and returning them to their masters. There is not a spot upon which a poor black fugitive may stand free -- no valley so deep, no mountain so high, no plain so expanded, in all that ‘land of the free and home of the brave,' that I may enjoy the right to use my hands without being liable to be hunted by the bloodhounds.3

Questions for Reading 3

1) What was the importance of New Bedford to Douglass?

2) What surprised Douglass about the Johnsons's house? How did the Johnsons typify the life of other free African Americans in New Bedford?

3) What was different for Frederick Douglass about the hard physical labor he did in New Bedford from that in Maryland?

4) If you were a slave who had escaped and become free, would you want to keep any part of your name that had been used while you were enslaved? Why or why not?

5) How does Douglass's speech in London add to his portrayal of life in New Bedford? Do you agree with his statement that slavery was an "American institution" instead of a southern one? Why or why not?

Reading 3 is compiled from Frederick Douglass,"Chapter XI" in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845) and John Blassingame, et al, eds. The Frederick Douglass Papers: Series One-Speeches, Debates, and Interviews, Vol. 1 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979).

1 Frederick Douglass, "Chapter XI:" in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845).

2 Ibid.

3 Frederick Douglass, "Emancipation is an Individual, a National, and an International Responsibility: An Address Delivered in London, England, on May 18, 1846," London Patriot, May 26, 1846. John Blassingame, et al, eds. The Frederick Douglass Papers: Series One-Speeches, Debates, and Interviews, Vol 1. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 249.

Determining the Facts

Reading 4: The End of a Journey

While Douglass was living in New Bedford, his advocacy work sent him throughout the Northeast, even abroad to Great Britain, to speak. In 1847, he moved to Rochester, New York to further pursue his abolitionist efforts. At the time, Rochester was known as a hotspot for reformers. Douglass founded the newspaper The North Star which advocated full rights for all, and he became a conductor on the Underground Railroad. In 1848, Douglass would participate in the famous Seneca Falls convention, a meeting that called for women's equality before the law. He would continue to advocate for women's equality throughout his life.

The Civil War did not end Douglass's work. During the war, he continued to advocate for freedom and equality:

What business, then, have we to fight for the old Union? We are not fighting for it. We are fighting for something incomparably better than the old Union. We are fighting for unity; unity of idea, unity of sentiment, unity of object, unity of institutions, in which there shall be no North, no South, no East, no West, no black, no white, but a solidarity of the nation, making every slave free, and every free man a voter.1

The war did not accomplish that unity, so Douglass continued to fight until the end of his life. He said, "Verily, the work does not end with the abolition of slavery, but only begins."2

After the Civil War, Frederick Douglass moved to Washington, DC, in the early 1870s. He first settled in Capitol Hill, in the southeast of the district. In 1877, Douglass purchased his final home, Cedar Hill, in Anacostia, also in the southeast of the district. When Douglass bought the property, it originally took up 9 ¾ acres of land. In 1878, he purchased an additional 5 ¾ acres. A newspaper described his house in the following way:

The residence of Mr. Douglass is in Uniontown, across the Eastern branch. No idea of the place can be given in a small picture. The grounds are fifteen acres in extent, and the house is surrounded by cedars, oaks and hickories and is almost hidden from the street. The building is of brick, two stories, high, in cottage style of architecture, and is very large, having eighteen rooms. A portico runs across the front and the main door is in the centre. The parlors are on each side of the hall. The house is very handsomely furnished and has the appearance of being the home of a cultured, refined gentleman. The library is in the rear of the east parlor. The books number about two thousand volumes and are very valuable. They cover history, poetry, philosophy, theology and fiction…it is a great pleasure to think that this man, whose intellect and energy have been his only capital, is now living in refined opulence instead of suffering in bondage as the property of ignorance, idleness and superstition.3

Cedar Hill became the headquarters for Douglass's advocacy work. It was also the final home for both himself and his first wife Anna who passed away in 1882. In 1884, Douglass married Helen Pitts, a white women's rights activist and the daughter of abolitionists. Douglass ran and owned the New National Era, a paper "devoted to the defence [sic] and enlightenment of the newly emancipated and enfranchised people."4 He continued to speak publicly for the civil rights of all Americans. In 1886, Douglass gave the following speech on the 24th anniversary of emancipation in Washington, DC:

The American people have this lesson to learn: That where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced, where ignorance prevails, and where any one class is made to feel that society is an organized conspiracy to oppress, rob, and degrade them, neither persons nor property will be safe.5

Douglass became the first African American appointed to various positions in the government (marshal, recorder of deeds, and minister). Despite the legal recognition given to African American men, Douglass continued to face prejudice based on his race. He wrote about the reaction to his appointment as a U.S. Marshal of the District of Columbia:

It came upon the people of the District as a gross surprise, and almost a punishment; and provoked something like a scream—I will not say a yell—of popular displeasure. As soon as I was named by President Hayes for the place, efforts were made by members of the bar to defeat my confirmation before the Senate. All sorts of reasons against my appointment, but the true one, were given, and that was withheld more from a sense of shame, than from a sense of justice.6

Douglass did not allow prejudice to hold him back. He continued speaking out until the day of his death. The New York Times wrote the following in his obituary, "Mr. Douglass, perhaps more than any other man of his race, was instrumental in advancing the work of banishing the color line."7

Douglass's tireless work to help people regardless of their race or gender makes him one of the most important figures of the nineteenth century.

After Douglass's death in 1895, his widow, Helen, formed the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association. The purpose of this organization was to preserve Frederick's home and materials after her death for all Americans. The National Park Service acquired the house in 1962, and it became a national historic site open to the public.

Questions for Reading 4

1. Why was Rochester a significant place for Douglass to live? What important events took place there?

2. When did Douglass move to Washington, DC? When did he move into Cedar Hill? Does the newspaper description of his house surprise you? Why or why not? Why do you think the author chose to talk about Douglass's library?

3. What does the response to Douglass's appointment as a U.S. Marshal say about the perception of African Americans in the United States after the Civil War? Does this reaction seem right? Why or why not?

4. Did Douglass think abolition would fix the challenges African Americans faced? What problems would there be after slavery was abolished? Why?

5. Do you think Douglass was one of the great men of the nineteenth century, white or black? Why or why not?

Reading 4 was compiled from the National Park Service, Frederick Douglass National Historic Site website and Virtual Museum Exhibit; "Frederick Douglass," Civil War Trust; "Death of Frederick Douglass," New York Times, February 21, 1895; Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: 1817-1882 (London: Christian Age Office, 1882); John Blassingame, et al, eds. The Frederick Douglass Papers: Series One-Speeches, Debates, and Interviews (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979); Philip Foner, ed. The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, Vol. 4 (New York: International Pub., 1950).

1 "Emancipation, Racism, and the Work Before Us," December 4, 1863, Annual Meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Blassingame, John, et al, eds. The Frederick Douglass papers: Series One—Speeches, Debates, and Interviews, Vol. 3 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 598.

2 "Frederick Douglass," Civil War Trust.

3 "Celebrities at Home. XXIII. Frederick Douglass," pp.565-566. The Republic, October 23, 1880, 566.

4 Frederick Douglass, "Chapter XIV: Living and Learning," in Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: From 1817-1882 (London: Christian Age Office, 1882).

5 Frederick Douglass, "Southern Barbarism," 24th Anniversary of Emancipation, Washington, DC, 1886 in Philip Foner, ed. The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, Vol. 4 (New York: International Pub., 1950), 434.

6 Frederick Douglass, "Chapter XV: Weighed in the Balance," in Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: From 1817-1882 (London: Christian Age Office, 1882).

7 "Death of Frederick Douglass," New York Times, February 21, 1895.

Visual Evidence

Illustration 1: Frederick Douglass Running Away.

Library of Congress

Visual Evidence

Illustration 1: Frederick Douglass Running Away.

Transcription

THE FUGITIVE’S SONG,

WORDS

composed and respectfully dedicated, in token of confident esteem to

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

A Graduate from the

"PECULIAR INSTITUTION"

For his fearless advocacy, signal ability and wonderful success in behalf of

HIS BROTHERS IN BONDS

(and to the FUGITIVES FROM SLAVERY in the)

FREE STATES & CANADAS.

by their friend

JESSE HUTCHINSON JUNE

BOSTON, Published by HENRY PRENTISS 33 Court St.

Questions for Illustration 1

1) In what ways does this drawing reflect escape attempts made by Douglass and other enslaved African Americans?

2) If you were newly freed, how would you feel about being featured in a song? Would you be proud or scared?

3) What do you think about the phrase "A Graduate from the Peculiar Institution"? Do you think this is the best way to describe Douglass's and other freedom seekers' experiences? Why or why not?

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: Wye House.

(Photo courtesy of Janet Blyberg)

Photo 2: Nathan and Polly Johnson House.

(National Park Service)

Photo 3: Cedar Hill.

(National Park Service)

Questions for Photos 1-3

1) Study the Wye House in Photo 1. This house has been compared to a seven-part Roman Country House, which was the type of home owned by wealthy Romans during the classical period. Does this look like a large or complex house to you? Window glass was expensive in the 19th century. What does the number of windows tell you about the owner?

2) Does it look like the one family living here could take care of the Wye House by themselves? Who might have done the work? (Refer back to Reading 1 if necessary.)

3) Compare the Wye House to the Nathan and Polly Johnson House and to Cedar Hill. Compare the Johnson House with Cedar Hill. What are the similarities and differences among all these houses? At the different points in his life, how would each house have been appealing to Douglass? Why?

4) If you were Frederick Douglass, looking back on these three houses you had lived in during your life, which do you think would be the most meaningful to you? Explain your answer.

Putting It All Together

By looking at "Journey from Slavery to Statesman:" The Homes of Frederick Douglass, students can more easily understand the various experiences of being an African American from the early to the late 19th century. The following activities will provide students with an opportunity to better comprehend the different experiences of enslavement and freedom and the lingering prejudices that remained after the Civil War.

Activity 1: The Life and Times of Me

Frederick Douglass's early autobiography, Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass (1845), amazed readers. It portrayed the horrors of slavery in evocative language, in a manner not expected from a newly freed man. It starts from his birth and continues through his escape to a new life. To include the rest of his life he later wrote two further autobiographies-My Bondage and My Freedom (1855) and The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881). His autobiographies emphasize the American values of hard work, education, and freedom. His long life encompassed slavery, the Civil War, and the difficult years after the Civil War when it was clear that African Americans were second-class citizens. Parts of the readings in this lesson plan come from his autobiographies.

Have students read a chapter or two from one of Douglass's autobiographies (these can be found online through a variety of sources). Then ask students to write a couple pages of their own autobiographies. First, have each student create a timeline of important events in his or her life. Next, have them think about what values are important to them in their lives. What values do they think they represent? What events in the community and in the world coincided with the important events in their lives? If possible, have students interview an author in the community to learn about the skills needed to write a book. Ask students to read their autobiographies to the class. Hold a class discussion about how events classmates have shared have had similar or different meaning among the students.

Activity 2: The Great Orator

Frederick Douglass was a famous speaker. He taught himself by reading a book of speeches, the Columbian Orator, over and over again. He practiced whenever he could once he lived in Baltimore and could come and go from his caretaker's house. He continued to practice when he lived in New Bedford. He was asked to go to Nantucket to talk about his experiences of slavery. It was his first abolitionist speech, but it so impressed the audience that he was offered a job as a traveling orator.

Have students learn part of a Frederick Douglass speech and recite it in class. Several examples of Douglass's speeches can be found at this Frederick Douglass website and his "Independence Day Speech at Rochester" can be found at this PBS website. Ask students to choose their favorite excerpt and explain why. Next, have students think about an event in their life that made a difference to them and write a short speech about why it was important. Have students deliver the speech to their classmates as if they do not have shared experiences. When choosing an event, students should provide context for their experience. Based on the scale of the event, students should explain what was going on in the community at the time (local, state, national, international). What external factors influenced their experience? What internal factors influenced their experience? How did the event make them feel? Were those feelings shared in the community? Was there anything that made their experience unique? Geography? Beliefs? Age? Gender? Ethnicity? Once everyone has presented, hold a class discussion highlighting how people can experience similar things in different ways based on various factors.

Activity 3: Traveling the Underground Railroad

To present students with a more personal understanding of the Underground Railroad, divide them into groups to read one of the slave narratives listed below. Have groups divide up the reading. As students read, have them trace the route that the freedom seeker took. Have students compare the maps from different slave narratives. How did the freedom seekers show resourcefulness and courage? Did anyone help him or her? Who was it? What became of the freedom seekers after the Civil War? Are their homes preserved or is there a marker or statue by which to remember them? If there is not a marker, what would you put on a historic marker or statue to commemorate this person? Where would you place it?

Have students create an exhibit using the information found in the slave narrative. Display the exhibits around the classroom and ask each team to explain its exhibit to their classmates. You might even consider displaying the exhibits in the school library or auditorium and arranging for the students to present their findings to other classes.

For narratives, see "Documenting the American South: Slave Narratives" website, especially:

-

Henry Bibb, Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb an American Slave Written by Himself (1849) [love story]

- Henry "Box" Brown, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, Written By Himself (1851) [mailed himself in a box] – sculpture at Riverwalk in Richmond

- William Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom; or the Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery (1860) [disguised] – hidden at the Lewis and Harriet Hayden House in Boston, MA (Boston African American National Historic Site)

- Josiah Henson, The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada as Narrated By Himself (1849) [Uncle Tom in Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe was said to be based on him]—Josiah Henson Park

- William Parker, The Freedman's Story in Two Parts (1851) [involved in a shootout] – National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom sites in Christiana, PA

- James W. C. Pennington, The Fugitive Blacksmith; or, Events in the History of James W. C. Pennington, Pastor of a Presbyterian Church, New York, Formerly a Slave in the State of Maryland, United States (1849) [became an important abolitionist minister]—private home on National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom

- John Thompson, The Life of John Thompson, a Fugitive Slave; Containing His History of 25 Years in Bondage and His Providential Escape. Written By Himself (1856) [became a whaler]

Federal and state laws did not prohibit slavery even in 1860. Have students research laws about slavery in their state. How and when did it end?

The United States economy was built on the system of slavery. In addition to Southern plantation owners, Northern cotton mills, insurance companies, and banks all profited from it. In the mid-nineteenth century, Americans proposed different "solutions" to the problem of slavery. Divide students into four groups and have each group study a different “solution” that Americans proposed:

-

Immediate emancipation

-

Compensated emancipation

-

Gradual emancipation

-

Colonization of freedmen outside the United States in Liberia or Haiti

Ask each group to describe their assigned proposal. Remind students that they are describing the proposal as historians, not advocating for it. Who would benefit from the proposal, if it were enacted? Who would be harmed? How did the proposal compare with Douglass's ideas? How did the proposal compare with what actually happened in the United States?

Activity 5: Modern Injustice

Slavery may have been ended with the Civil War but other great social injustices in society continued or came about later. Have students search for an example of social injustice in their community (past or present). Have students search popular media outlets for discussion of their issue. How is it portrayed? Does it seem important to people? Have students survey friends and family members and make a chart of their responses. How do most people react to this issue? How do the reactions of people today to social injustices compare to the reaction to slavery of Douglass and fellow activists? Do people have suggestions for solutions? Have students come up with some of their own solutions. Are there any local organizations where students can volunteer to help solve the modern problems? Have students consider a modern injustice like homelessness or inequality of health care and consider volunteer work to address the problem. If possible, have students interview a local official about the problem. What suggestions does the official have for addressing the problem? Were they aware of its history? If the issue is not receiving a lot of attention, have the official explain why certain issues take precedent over others. Students should write a report about their findings and submit it to the local archive or library.

Supplementary Resources

Frederick Douglass National Historic Site

Frederick Douglass National Historic Site is a unit of the National Park Service. The park's website contains numerous resources to learn about Frederick Douglass and his home, Cedar Hill, in Washington, DC.

New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park

New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park is a unit of the National Park Service. The park's website offers a variety of resources discussing the history of New Bedford and its whaling history. Included on the site is an online tour of the community that includes the home of Nathan and Polly Johnson.

TwHP Feature: African American History

This collection of Teaching with Historic Places lesson plans examine various aspects of African American history in the United States.

Frederick Douglass Home on Alexander Street

This history of Douglass's home in Rochester, New York covers his role in the Underground Railroad and his experience living in a place where many people were initially hostile to him.

Biography.com: Frederick Douglass

This website provides a detailed biography on Frederick Douglass. It also has video a 45 minute video (approximately) about Douglass. Related video content is also available covering the Civil War, abolition, and women's rights.

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress holds a number of Frederick Douglass's papers. The site also offers suggestions for critical thinking and arts and humanities activities. The Library of Congress also has a collection of Frederick Douglass: Online Resources that offers a variety of links to content, activities, exhibits, photos, and other resources discussing Douglass.

Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936-1938 contains more than 2,300 first-person accounts of slavery and 500 black-and-white photographs of former slaves. These narratives were collected in the 1930s as part of the Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and assembled and microfilmed in 1941 as the seventeen-volume Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves.

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The library at UNC Chapel Hill offers digital copies of slave narratives in their "Documenting the Old South" online collection. Included in this collection are the three autobiographies of Frederick Douglass. A Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881).

For Further Reading

For more about Frederick Douglass, check out his three autobiographies. These can be accessed online at the UNC Chapel Hill library: A Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881).

Teach Civics with this Lesson

-

Voting Rights

Voting RightsHow is the COVID-19 pandemic affecting voting rights? What are remedies for low voter turnout?

-

First Amendment Freedoms

First Amendment FreedomsHow have people engaged their First Amendment freedoms throughout U.S. history?

-

Teaching Engaged Citizenship

Teaching Engaged CitizenshipUse these mini-lessons to fit civics education into a variety of social studies classrooms.

Tags

- frederick douglass

- frederick douglass home

- frederick douglass national historic site

- teaching with historic places

- african american

- antebellum era

- twhp

- slavery

- african american history

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- washington d.c.

- dc history

- anacostia

- maryland

- maryland history

- massachusetts

- massachusetts history

- national historic landmark

- twhplp

- ea aah

- cwr aah

- ga aah